Why food is so pricey

Canadians can’t think their way out of grocery-store sticker shock, but the way we view food would benefit from a change

Share

In May, Statistics Canada reported that Canadians are paying nearly 10 per cent more for food than they did in 2021: meat and fresh fruit are up by 10 per cent, rice is up by roughly seven per cent and pasta has shot up by almost 20 per cent. This means it will cost an extra $966 to feed the average family of four this year, according to Canada’s Food Price Report.

Recently, the U.S. Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken boiled down the accelerating inflation of food prices to three C’s: COVID, climate and conflict. Repeated lockdowns, migrant-labour shortages and strained supply chains are being reflected at the register. Last year, droughts in South America devastated countries that provide half of the world’s soybeans, and in Ukraine—often called “the breadbasket of the world”—the war with Russia is now interrupting harvests of wheat, barley, corn and sunflowers.

Poverty and inequality are the main drivers of food insecurity. When food is consistently treated as a market-driven commodity, you inevitably get the kinds of price volatility that Canadians are seeing at the moment. Access to food should be treated as a right, not a purchasing decision. I’m not talking about flat-screen TVs here; I’m talking about the necessities of life. The best examples of what Canadians can achieve when we expand our thinking are our publicly funded health care and education systems. They’re far from perfect, but these are resources that citizens feel entitled to now—and this was not always the case.

The current grocery sticker shock should be motivation enough for governments to explore public-sector procurement from small-scale, regenerative and organic food producers. It’s easiest to start in hospitals and schools, and Canada could take inspiration from other countries: in 2010, Italy passed a bill that requires schools to use local, organic produce to prepare meals from scratch in their own cafeterias. German public schools began providing students with full, warm meals—not just snacks—as they returned to in-person learning. Currently, Canada is the only G7 country without a national school food program. Providing every child, from kindergarten to Grade 12, with access to a healthy snack or meal at school would take pressure off family budgets.

Right now, initiatives are patchwork across the country, but at least provinces have started to invest. Prince Edward Island has its own government-subsidized School Food Program. It’s a pay-what-you-can model that covers two weeks of lunches up to $5 per meal. Many experts think it has the potential to scale. In 2020, Quebec expanded eligibility for its school meal program—previously limited to low-income families—to include all preschool, elementary and secondary students. And Alberta renewed funding for its School Nutrition Program, despite a change in government a few years ago.

In 2022, the food supply chain is dominated by a handful of big, transnational players, from farm to fork. For example, three supermarket chains—Loblaw Companies Ltd., Empire Company Ltd. (which owns Sobeys) and Metro Inc.—earn 60 cents of every dollar that Canadians spend on groceries. Smaller producers, processors and distributors, as well as wholesalers and retailers, stand to benefit from a shift. Half of Canada’s food businesses are micro-enterprises—mom-and-pop operations. It would be good to bolster them with government dollars so they can make a decent living.

Quebec is a good case study. Since the pandemic, there’s been a growing movement within the province to prioritize its own food production. Protecting Canada’s domestic food production is a key piece in controlling food prices, but there’s no magic bullet that’s going to cure the current affordability crisis. It’s crucial for Canada to reduce our dependency on global trade in order to feed our own population. And this will be important long after fruit and vegetable prices return to normal.

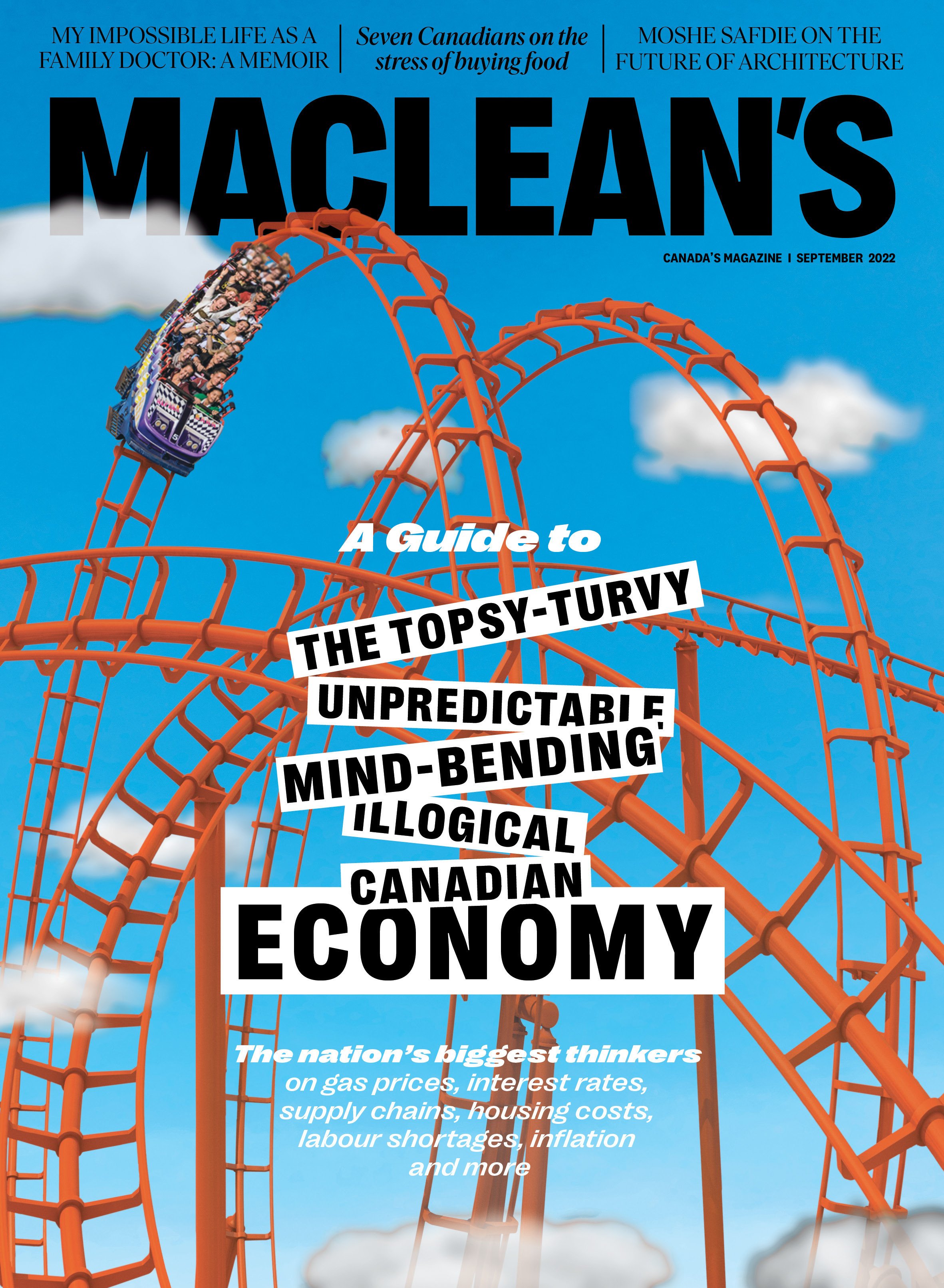

This is part of the Maclean’s Guide to the Economy, which appeared in the September 2022 issue. Read the rest of the package, order your copy of the issue, and subscribe to the magazine.