Canadians are Alberta-bound no more

For the first time in years, more people are leaving Alberta than moving to it.

Brandon MacKay, pictured in Fort McMurray Alberta, November 14, 2015. Brandon MacKay was recently laid off from his job. Jason Franson for Maclean’s Magazine.

Share

Albertans have had to say goodbye to a lot during these last 18 months: the days of $100 oil, the word “boomtown” surgically grafted onto Fort McMurray’s name, thousands of jobs, the provincial Tory dynasty, and a hometown Prime Minister. We’ve now started saying goodbye to each other in greater numbers.

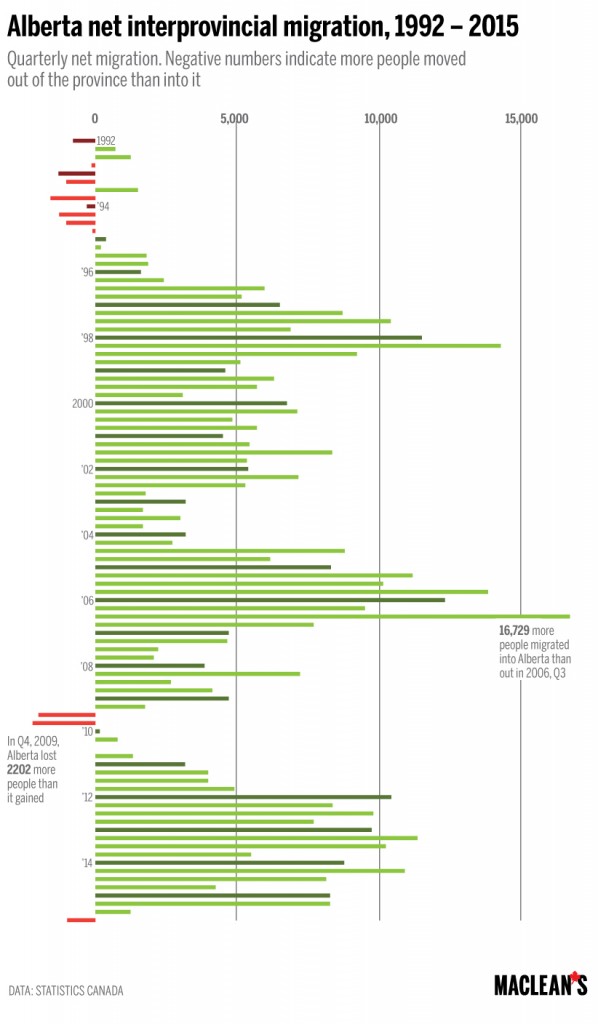

For decades, one of Canada’s biggest power dynamics was that large sucking sound from Alberta, hoovering up job-seekers from other provinces. And lo, Statistics Canada on Wednesday reported that 977 more people left this well-oiled province than moved in during the last three months of 2015. That’s the first quarter of negative interprovincial migration for Alberta since late 2009 at the end of the Great Recession—and before that bad spell, Alberta had been a net gainer since the early 1990s, when the province finally began pulling itself out of the economically nightmarish ’80s.

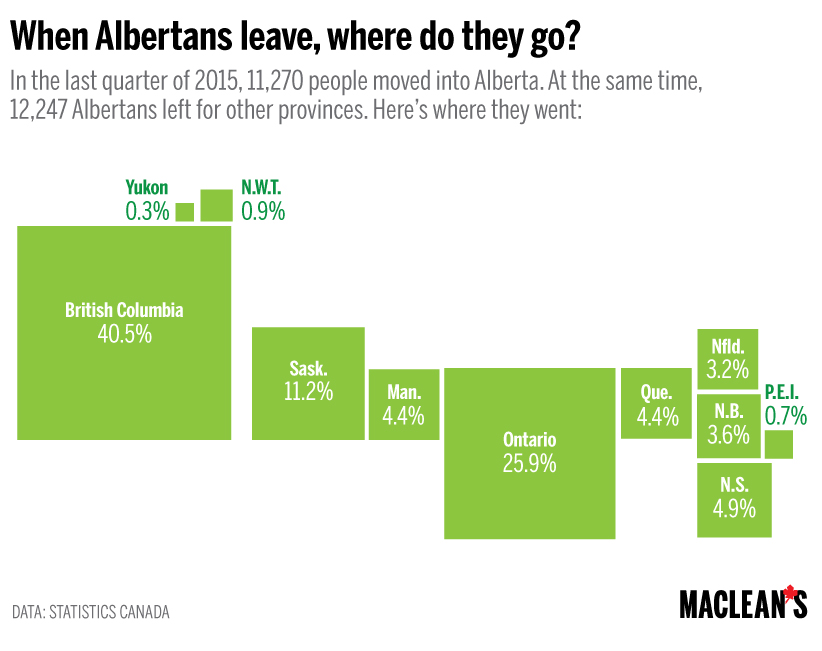

Living in Alberta it’s rare to be in a workplace or at a social gathering without running into at least a few people who have a Saskatchewan Roughriders jersey at home, or really miss Montreal bagels, or lapse into a Newfoundland lilt when on the phone with Mum. Now, people have begun flowing back home, or seeking adventures anew elsewhere. Here’s how Donald Trump would explain it: “We’re losing to Nova Scotia! It’s terrible! We’re losing to Ontario! We’re losing to British Columbia! And my god, we’re losing to New Brunswick! It’s terrible!”

Population move-outs always come later in an economic downturn. “At the start of a downturn, the layoffs come a little later. Then once you’re laid off you have to make the decision ‘Am I going to stay or am I going to go?’, and it all takes time,” says economist Rob Roach of ATB Financial. Somebody laid off from an oilsands work camp can return to Cape Breton or Windsor the next day, while a homeowner or apartment renter must make a bigger decision, and unload their property.

This will also show in the sliding real-estate market.

Related: The death of the Alberta dream

“And it’s also fewer people moving in, now that low oil prices have been with us for quite a while now, people have now heard of this. At the start, they might have said, ‘No, it’s temporary, I’ll head out there and find some work’,” Roach says. “But now it’s sunk in to people from other parts of the country that it’s probably not the best time to move to Alberta. Unless you have a job lined up.”

All is not on the downside in Alberta. Between immigration and a natural increase (more births than deaths), the province still grew by 15,084 people last quarter, better than the Canadian average. But people leaving Calgary and Medicine Hat for Canso, N.S., and Markham, Ont., will continue to be a drag on that growth as the job market stays lousy.

In better times Alberta regularly gained interprovincial migrants by the thousands; in the second quarter of 2014, close to 11,000 more people came to the province than left. The boomerang of the bust would likely be worse if economies were substantially more robust elsewhere, which explains why the Roughrider fans aren’t rushing back to Saskatchewan, which is also shedding jobs because of the oil sector’s crash.

“If you’re sitting in Alberta right now, it’s not obvious where you would go to find work. Where’s the hotspot?” Roach says. “B.C.’s doing OK. You might want to go home because you’ve got a safety net and familiarity there, but it’s not sort of obvious (you’ll) move to Saskatchewan or Ontario because they’re not really booming… If you had lost your job in Alberta, you might say ‘I’m going to wait it out’.”

Ontario doesn’t have the same strong manufacturing sector it had in the 1980s, when it served as safe harbour for many Albertans coping with a lengthy financial crisis plus high mortgage rates. But Ontario picked up 3,170 Albertans while 2,843 went the other way the last quarter—the first time the quarterly flow tipped in Ontario’s favour since early 2002.

Quebec isn’t yet a net beneficiary of Alberta’s woes, but that could change. Last month, the Alberta unemployment rate (7.9 per cent) surpassed Quebec’s for the first time since 1987.

Alberta should expect a few more quarters of more goodbye parties than welcome wagons through 2016. Because population is a lagging indicator, any sustained rebound in oil prices or economic growth in Alberta will take time to show up in the movement of people.

“Fingers crossed, things will probably pick up again in 2017,” Roach says. For now, that might as well be Alberta’s official hand gesture.