And the engine of Canadian resourcefulness is…

Memo to Trudeau: Canada’s resourcefulness engine is in the same province as its resource engine

Children run up to the sculpture Wonderland by Spanish artist Jaume Plensa, in downtown Calgary, Alta., on Sunday October 18, 2015. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

Share

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s pledge at Davos last week to change the world’s view of Canada from a country known for its “resources” to one recognized for its “resourcefulness” has come in for some well-deserved criticism. The implied message was that resource extraction is somehow beneath Canada because it requires mere brawn, whereas the country should instead aim to be known for what’s “between our ears.”

Digging stuff out of the ground, of course, is far more complicated than Trudeau made it out to be. And even he seemed to walk back the comment when MPs returned to the Hill this week, with Trudeau declaring—rather convolutedly—that his resourcefulness includes resources: “When we talk about the resourcefulness of Canadians, we include the natural resources sector and the people who work extremely hard to innovate, to create technologies, to build on science, to ensure that while they are working hard we are creating the very best of value to everything we have to offer the world.”

So here’s a question: if resourcefulness is to be the all-encompassing engine of Canadian growth, where will it be grounded? Arguably one of the best ways to gauge a country’s ability to innovate, and hence be resourceful, is to look at patent filings. Thanks to a newly updated OECD patent database, which drills down to the regional level across member nations, we’re able to see exactly how innovative Canadian cities have been.

If the last 15 years or so of patent applications are any indication, Canada’s resourcefulness engine is in the same province as its resource engine. Between 2002 and 2012 Calgary saw the biggest jump in the number of annual patent applications of any area in the country.

Calgary isn’t neccessarily the largest source of new patent applications—that would be Vancouver, followed by Ottawa, Montreal and Toronto. (You can see the top 10 cities for patents and how they’ve changed since 1990 in a chart I made here. All city names refer to their greater metropolitan areas.) What sets Calgary apart, though, is the remarkable increase in the number of patent applications over a time when application growth stumbled or flatlined elsewhere. For instance, going as far back as 2000 the number of patents coming out of Toronto and Montreal remained almost unchanged, despite ups and downs along the way.

Since the OECD data doesn’t break out what types of patents these were in sufficient detail, it’s impossible to say how many applications from Calgary related to the resource sector. And of course, since the database update only brings us to 2012, it doesn’t reflect what’s happened since the oil crash brought Alberta’s energy sector to its knees.

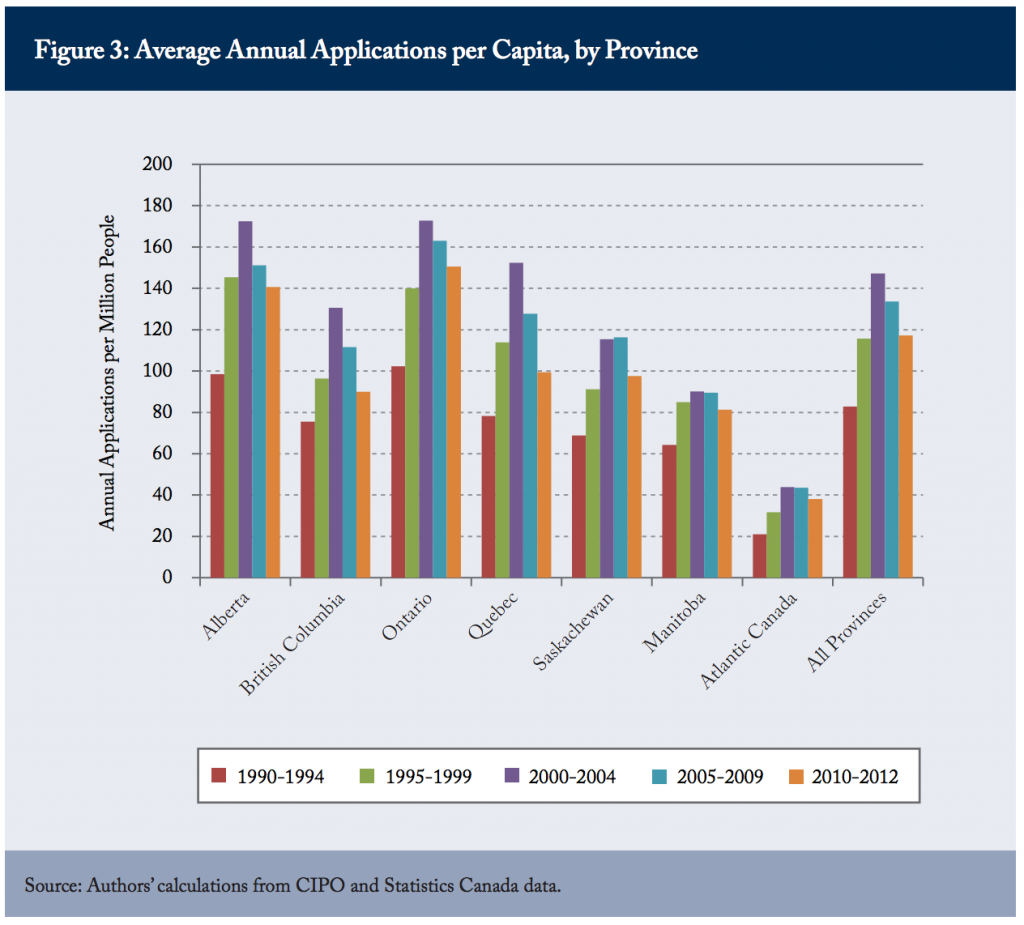

But there’s good reason to think that even after the oil bust, Alberta will punch above its weight in patents. In 2014 the C.D. Howe Institute released an analysis of several decades of patent activity in Canada. When measured on a per capita basis, Alberta and Ontario lead the country in patent applications. In the case of Alberta, it didn’t seem to matter whether oil was booming or not. “Alberta outperforms both the national average and the other Western provinces, suggesting that it is a hub for patenting activity,” the report’s authors note.

That report should also serve as a warning to Trudeau, however, as he attempts to project a new economic persona for Canada on the world stage. Since the early 2000s, patent applications in all provinces have been on the decline, on a per capita basis.

Maybe it’s a good thing we have all those resources to back us up in case our resourcefulness doesn’t live up to Trudeau’s billing.