B.C.’s new subsidy for homebuyers is pure politics and bad policy

By offering interest-free loans, B.C. is encouraging residents to take on bigger risks, with all the benefits going to existing homeowners and developers

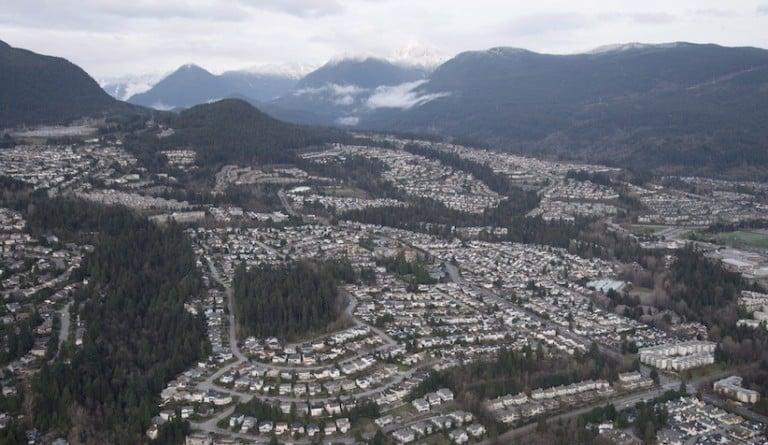

Houses are pictured from the air in Port Moody, B.C., Friday, Nov. 25, 2016. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jonathan Hayward

Share

With an election less than five months away, Christy Clark’s B.C. Liberal government is into full-on election mode and the countless government spending announcements that come with it. This past Thursday, the government rolled out its newest election-season offer: the B.C. Home Owner Mortgage and Equity Partnership Program, carrying a price tag of $703 million over three years. The program’s stated goal is to “ensur[e] the dream of home ownership remains within reach of the middle class” by providing first-time home buyers in the province with 25-year, matching loans worth up to $37,500 for their down payment. No interest would be accrued or payments required over the first five years of the loan.

The response from economists and other housing experts has been nearly unanimous: in the words of professor Tom Davidoff of UBC’s Sauder School of Business, “it’s terrible policy.” In an overheated housing market with substantial constraints on the supply side like Vancouver or Victoria, this kind of demand shock will simply lead to increased home prices, with the vast majority of benefits accruing to existing homeowners and developers.

The policy not only fails to address its stated goal, but it does so while encouraging young British Columbians to take on more debt than they would otherwise have. It’s difficult to see what economic rationale the province may have to encourage its residents to engage in more risk-taking. If it turns out that the recent appreciation in British Columbian housing values has been, at least in part, a housing bubble, this could have truly disastrous consequences.

The policy’s most overlooked economic failing is in its opportunity costs, as noted by professor Joshua Gottlieb from the Vancouver School of Economics, who has argued that “a grant to new home buyers will ultimately require raising tax rates on working families in B.C.—rates that are already very high.” For a program that does little more than transfer wealth to existing homeowners and developers, it wouldn’t be difficult to find dozens of alternative programs or tax reductions that would provide greater social value.

So why would a government that has been in power for so long implement such a horrendous piece of policy? Politics, plain and simple. And while some commentators think that the policy was “well intentioned,” it has the trappings of a carefully designed electoral offer with little regard for non-political outcomes.

Over the first three years of the B.C. Liberals’ current mandate, housing affordability was their single greatest vulnerability. Clark’s former Vancouver–Point Grey rival, NDP MLA David Eby, successfully channelled the public’s frustrations over rapidly increasing home prices and collapsing vacancy rates. In an effort to control the damage on the file, the government introduced a 15 per cent tax on foreign homebuyers in Vancouver, which, while similarly panned by economists, has proven to be quite popular.

Early reports suggest that the foreign buyer’s tax may actually be having an impact in the Vancouver real estate market. However, for a government seeking re-election in five months, the last thing Clark wants to see is a slowdown in economic activity. Since the political value in the foreign buyers tax is less about actual price decreases than it is about the perception that the government is doing something, the government clearly felt that it had the political space to move forward with a countervailing measure.

That’s one side of the political motivation behind the new subsidized loan program, but even in the absence of the foreign buyer’s tax the government may have opted to offer up this subsidized loan scheme. Why? The benefits of the subsidized loan program accrue entirely to British Columbians who are very likely to vote and donate to political campaigns: existing homeowners, developers, and potential new homeowners. Further, on average these voters are more likely to be within the voting universe of the B.C. Liberal Party.

It’s for these reasons that the government has chosen this path over the otherwise superior B.C. Housing Affordability Fund proposal that would tax vacant properties or a broader investment in affordable housing. Both of these options would actually address the policy problem in that they shift the supply of housing rather than the demand for it, but fail in that many of their benefits go to renters who are less likely to vote.

It shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone that a government has chosen to try and maximize its odds of re-election through a policy choice, but what is particularly egregious about this case is the complete disregard for the quality of the public policy. We need to demand better from our elected officials and, in the case of British Columbia’s housing crisis, that means pushing them to take concrete steps to increase private sector housing supply or affordable housing.

Rob Gillezeau is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Victoria with expertise in economic history, labour economics, and public policy. He previously served as the Chief Economist in the Office of the Leader of the Official Opposition for the NDP.