Canada’s not-so-great expectations about house prices

Why the Bank of Canada is so worried about the unrealistic expectations driving house prices in Toronto and Vancouver

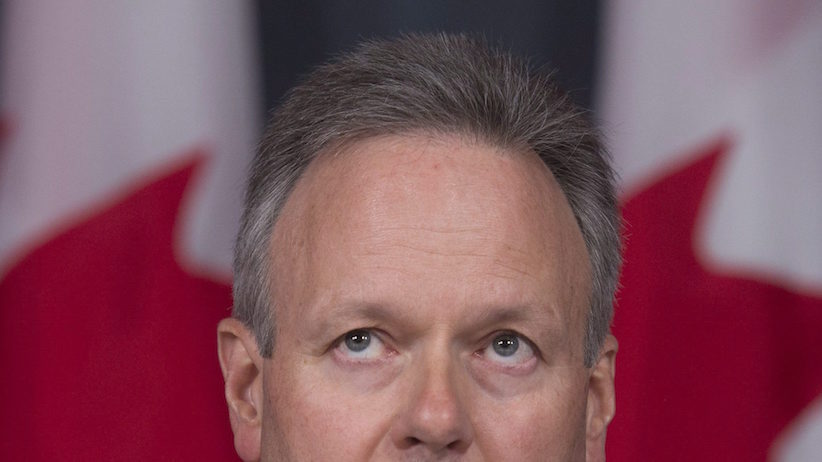

Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz speaks about the Financial System Review during a news conference in Ottawa, Thursday,June 9, 2016. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Adrian Wyld

Share

Central bankers aren’t known for being blunt. Alan Greenspan, the former chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve was famous for his “opaque utterances” and even though the current generation of central bank chiefs strive to be more transparent, their words still leave lots of room for parsing and interpretation.

In releasing the Bank of Canada’s latest financial system review on Thursday, Stephen Poloz, Canada’s top banker, tried a new approach to address surging house prices in Vancouver and Toronto: central banking by sledgehammer.

“If prices are going up because people expect prices to go up, that of course is probably unsustainable and those expectations will not be realized in the longer term.”

Sorry, Mr. Poloz, what are you saying?

“In these two areas [Toronto and Vancouver] we see a rate of price increase that would be very difficult to match up with any definition of fundamentals that you could point to.”

Come again?

“When people say ‘Well, I need to buy a house because I’m worried that prices are going to go up this much again next year and I’ll be priced out of the market’ … In our opinion the fundamentals do not justify that kind of extrapolation.

You don’t need a formal model or a specific analysis to make that assertion.”

Ah, in other words, any fool can see Canada’s two hottest housing markets have become completely detached from reality.

Why didn’t you just say so?

The surge in prices in the two cities over the last year has indeed been jaw-dropping—up 15 per cent from last year in the case of Toronto and 30 per cent in Vancouver. That Poloz has now embraced such frank language after earlier gentle warnings about overheating markets failed to get his message across suggests the Bank is growing genuinely fearful of what’s ahead. To be sure, Poloz still clung to the tightrope he’s been on for the past few years when it comes to questions of a bubble in Canadian real estate—he refused to entertain reporters’ entreaties that he speculate on outright price declines, and despite arguing that fundamentals in no way support such frantic appreciation, he still trumpeted the “strong” fundamentals of Toronto and Vancouver—but something has definitely changed in the way the Bank views the two markets.

What the Bank no doubt worries about is the role that unrealistic price expectations have played in every asset bubble of the last 500 years. Humans suffer from a host of cognitive shortcomings that can make us do really dumb things sometimes. One of the ways our brains fail us is recency bias—the tendency to believe that trends we’ve seen in the recent past will continue to unfold into the future. We’re also social animals, fearful of missing out—when all our peers are buying homes, and those homes are soaring in value, the pressure to participate is immense. Combined, those two traits make it easier to believe massive annual price gains are the new normal. Meanwhile, as home buyers and real estate investors come to expect they’ll be able to resell a house at a higher price in the future, that invariably leads to even higher prices in the present. This is what Poloz meant when he highlighted the risk from “self-reinforcing expectations.”

The tendency of people to extrapolate that prices in the future could only soar up, up, up was key to inflating the U.S. housing bubble of the early 2000s, according to an IMF working paper released last year. It found that price expectation shocks accounted for 30 per cent of the increase in home values between 1996 and 2006, larger than all other factors driving price gains, such as housing supply, housing demand or mortgage rates.

It’s not only domestic home buyers the Bank of Canada is worried about, either. Carolyn Wilkins, the senior deputy governor at the bank, said the same temptation to believe prices will keep rising at these torrid rates applies to foreign buyers, too. There’s been a lot of focus on the role of foreign buyers, particularly from mainland China, in Canadian housing markets, especially Vancouver. While Wilkins admitted that the data related to foreign buyers in Canada is “particularly poor” there’s no question the phenomenon is occurring. The real worry in the eyes of the Bank is how “sticky” those foreign buyers are. When the pace of price increases inevitably slows, or turns to outright declines, will those foreign buyers cut and run?

But buyers, whether they’re domestic or foreign, aren’t alone in being susceptible to irrational price expectations. “We’re concerned not just about buyers, but also lenders,” Poloz said, describing lenders as “the first line of defence” in ensuring the mortgages that do get issued are to people who can actually afford them. If lenders also come to believe that prices will continue to climb at double-digit annual rates, there may be a tendency to lower lending standards even further than they already are.

By the way, if you’re wondering what extrapolation looks like—in other words, what’s keeping Poloz and Co. up at night—here’s a chart we made back in March which took house price expectations to their most ridiculous extreme, assuming 17 per cent annual gains for years to come.

It wasn’t long before realtors were sharing the story and chart as a warning to potential buyers that they’d better jump into the market before it’s too late.

It was to be expected.