Cities are facing a coronavirus fiscal crisis

Analysis: Canada’s cities are under intense fiscal strain from COVID-19 and Ottawa and the provinces will soon need to act

Vancouver City Hall is pictured in Vancouver, B.C. Thursday, March 19, 2020. (Jonathan Hayward/CP)

Share

Jack Lucas is associate professor of political science and Trevor Tombe is associate professor of economics at the University of Calgary

To control the spread of coronavirus, vast numbers of Canadians are staying home and keeping a safe distance from others. While this is necessary to slow the virus, it comes with significant costs to individuals, businesses, and governments. It means sudden increases in government spending, decreases in revenue, and dramatic increases in public debt.

We rightly focus on the fiscal strain on Canada’s federal and provincial governments, but we mustn’t forget about municipal governments. Their challenges are unique, and their ability to cope more limited.

Property tax deferrals, potential defaults on payments by homeowners and businesses, waiving fees on many city services such as transit and parking fees—all of these policy choices mean less revenue for local services. For Ottawa and the provinces, public debt provides a shock absorber. For most municipal governments, however, this option is heavily restricted.

As a result, Canada’s cities are under intense fiscal strain from COVID-19. And our local leaders know it.

READ: Coronavirus in Canada: These charts show how our fight to ‘flatten the curve’ is going

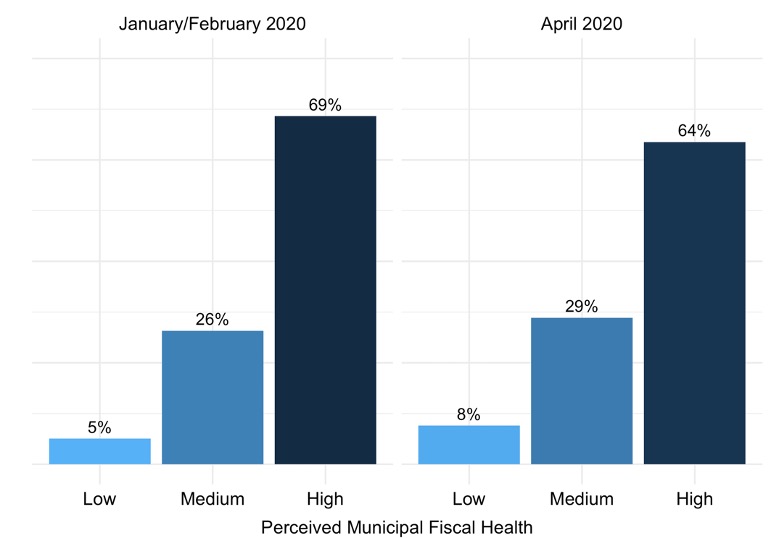

Data from the Canadian Municipal Barometer provide a unique insight into municipal leaders’ thinking about their fiscal situation. In January and February of 2020, just before the pandemic, we asked mayors and councillors across Canada to rate their municipality’s fiscal health on a scale from 0 (fiscal crisis) to 10 (perfect fiscal health). In the past two weeks, we went back to the same local leaders with the same question. Comparing these responses allows us to understand how much the pandemic has shifted local leaders’ perceptions of their municipal government’s fiscal health.

In the figure below, we summarize the percentage of our respondents who considered their municipality’s fiscal health low (0-3), medium (4-6), and high (7-10) in the two surveys. The results suggest that attitudes have indeed shifted, with a smaller percentage in the “high” category and a larger percentage in both “low” and “medium” fiscal health.

Given the extraordinary upheavals of the past month, these changes are surprisingly modest. But the overall numbers are misleading. Even today, in the heart of the pandemic, many rural municipalities have zero reported cases of COVID-19, while big cities like Toronto and Montreal have thousands. Canada’s big cities face a challenging one-two punch: they are particularly hard-hit by the pandemic and also responsible for an especially diverse array of services. We would expect to see more pronounced changes in perceived fiscal health among Canadian Municipal Barometer respondents from larger municipalities.

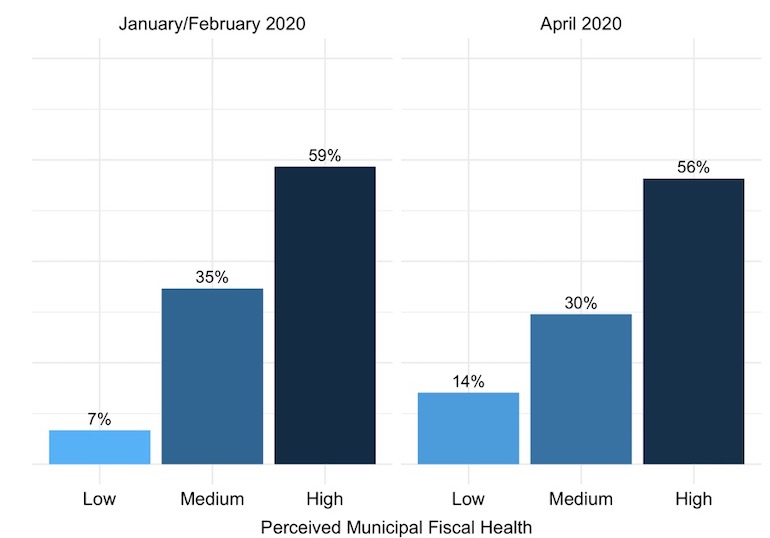

Our second figure, below, is identical to the first but only includes responses from cities above 100,000 residents. The results are striking: in a period of just weeks, the percentage of mayors and councillors who place their municipality in the “low” fiscal health category has doubled from seven to fourteen percent—a stunning shift in so short a span of time. Nearly one in six leaders in these cities tell us their municipality is closer to fiscal crisis than to perfect fiscal health.

Their concerns are not misplaced. And, if anything, they appear too optimistic.

Canada’s municipalities were expected to see roughly $200 billion in revenue this year. Roughly one-third of that is from property taxes, another third from transfers from provincial governments, and the remaining third from sales, fees, excise taxes, and other sources. COVID-19 and the resulting lockdown will cut into most of these sources substantially. With transit ridership low, recreation facilities closed, building activity stalled, park revenues evaporated, and property taxes deferrals at risk, the fiscal hole for municipal governments may be hard to manage.

For each 10 per cent of property owners who cannot pay their taxes in Vancouver, for example, the municipal government there will lose $80 million. For each 10 per cent who cannot pay across the country, the total revenue loss may exceed $6 billion. Toronto recently estimated various scenarios. A three-month lockdown and gradual recovery might create a $1.5 billion shortfall, they estimate — over 10 per cent of their total budget. For perspective, if this applied nationally, the shortfall could reach $20 billion across all of Canada’s cities. Though significant uncertainty remains, and smaller cities are at less risk, it is clear that significant fiscal stress for local governments is a reality in Canada.

How should governments respond?

In the short-term, direct support to municipalities may be needed. For perspective, the United States earmarked US$67.5 billion for direct support of local governments within its recent $2.2 trillion COVID-19 relief package. Only available to cities with populations above 500,000, the funds will help offset costs related to city pandemic responses. A similarly large package in Canada would total over C$10 billion. This is potentially the magnitude of support that may be required.

In addition to direct support, provinces may also extend greater flexibility to municipalities to borrow during this unique shock. British Columbia, only a few days ago, did just that. And even if direct borrowing is restricted, borrowing from internal capital reserves will become widespread.

Beyond fiscal measures, governance reforms have also been floated in the past two weeks. Long-standing calls to rethink “who does what” in Canada’s provincial-municipal systems are likely to grow as the pandemic reveals the challenges municipalities face in policy areas like public health and long-term care.

Different provinces will respond differently. And each city faces its own unique challenge. But most will see strain, and since local governments account for roughly one-fifth of our country’s total government spending, this will matter for us all. Whatever the details of our local fiscal responses to COVID-19 may prove to be, action will soon be needed.