How China went from economic miracle to military threat

We used to be in awe of China’s economy. Now we fear their sabre-rattling, writes Jason Kirby

Soldiers of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of China arrive on their armoured vehicles at Tiananmen Square during the military parade marking the 70th anniversary of the end of World War Two, in Beijing, China, September 3, 2015 (Damir Sagolj/Reuters)

Share

From the moment China’s economy lifted off last decade, the world was spellbound by its transformation from poverty-stricken backwater to economic superpower, the entire country at times resembling one massive construction site. And so we marvelled at reports that China was building 12 to 24 megacities a year, a full-size replica of Manhattan, a full-size replica of the Titanic (yes, the Titanic), at least one world-scale power plant each week, and even a plan, unveiled two years ago, to erect the world’s tallest skyscraper in under three months.

Never mind that the skyscraper project today remains a gaping, water-filled pit in which some enterprising locals have been raising fish, or that many of China’s most audacious projects were economic tomfoolery. (Ghost cities, anyone?) The point is that China’s remarkable rise fit comfortably into a “miracle” narrative that saw it aspire to be the world’s largest economy, and a cornerstone of peaceful and robust global growth for decades to come. We’re now in a period when that narrative is being dramatically tested, and the potential for things to go wrong should not be underestimated.

A chest-thumping military parade to commemorate China’s Second World War victory over Japan last week was just the latest display of sabre-rattling from Beijing. Over the last year, China has been on a frenzied island-building campaign across the South Pacific, dumping sand and rock on reefs as far as 800 km from the mainland, then erecting military ports and airstrips on them. True, President Xi Jinping used the military parade to announce he would reduce the size of his country’s army by 300,000 troops. And yes, that soothed some worries among his closest neighbours. But military analysts were quick to note that the move was primarily aimed at modernizing and strengthening the army. Any peaceful overtures were overshadowed by the coming-out party for China’s newest high-tech war machines, including a ballistic-missile system with a range of 4,000 km, capable of reaching U.S.-controlled Guam.

It’s no coincidence this is all happening as China’s economy slips deeper into malaise, and the economic reforms touted by Xi—meant to transition the economy from its reliance on wasteful investment spending to domestic consumption—appear to be faltering. Growth has sputtered, consumer spending is in retreat, and China’s exports and imports are both down sharply. The more China’s economy slows, threatening the economic gains its huge middle class enjoyed over the last decade, the more conspicuous Beijing’s military ambitions have become.

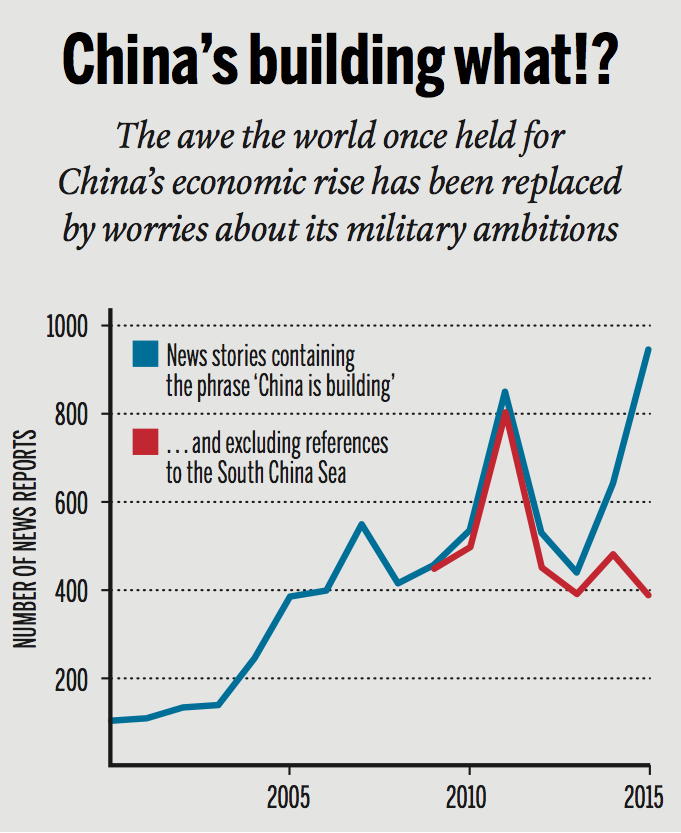

The world has taken note. That awe once reserved for China’s miraculous economic transformation has given way to levels of unease not seen in 30 years. The chart on this page partly illustrates that. The Western media’s obsession with what “China is building” soared as the country’s massive stimulus program in 2008 kicked into gear—all those new cities, factories, airports and railway lines—but has since been eclipsed by concerns over China’s island-building offensive.

This could also explain the newly skeptical attitude being taken toward Chinese statistics. China’s economic data, from its official GDP figures to employment statistics, have long bore little resemblance to reality, yet Western investors, companies and politicians willingly suspend their disbelief, because at least the nation was headed in the right direction. China’s insistence that its economy continues to grow at roughly seven per cent, despite all the evidence to the contrary, has completely failed to slow the rush of capital fleeing the country.

There are any number of ways this new confrontational tone could lead to a crisis between China and the West. For one thing, China’s economic rout could easily get away from Beijing’s control. Despite China having spent an estimated US$240 billion to prop up the stock market, panic has ensued. If the pace of growth falters further, and consumer confidence wanes, China’s Communist party—which has enjoyed unchallenged authoritarian control, as long as it delivered rising prosperity to the masses—may double down on its militaristic appeal to nationalists.

On this side of the Pacific, Donald Trump’s seemingly unstoppable presidential campaign is equally problematic. Trump has successfully tapped into America’s worst isolationist and jingoist tendencies. Whether he wins or not, he may very well succeed in pushing the political needle further toward isolating and confronting China.

No one wins in these scenarios—not China, the West or the rest of the world. Military tensions and trade threats would only put the tenuous global economy further on its heels. Here’s hoping for another miracle.