Is Canada at risk of a balance sheet recession?

A Q&A with Richard Koo, one of the world’s top economic thinkers on the dangers of debt and deleveraging—and why Canada should watch out

(Shutterstock)

Share

Richard Koo, the chief economist at Japan’s Nomura Research Institute, is widely regarded as an expert on the dangers of “balance sheet recessions,” a term he coined to explain why Japan’s economy has continued to struggle despite incredibly low interest rates. Earlier this week Maclean’s wrote about Koo’s research and what lessons it might hold for Canada. As it turns out, Koo just released a report to clients examining the economies of Australia and Canada, in which he writes, “While Canada exhibits none of the signs of a balance sheet recession at present, the sharp increase in household debt due to rising house prices means it is at risk of developing one.”

In an interview from Japan, Koo talked about that risk and how Canada should respond.

For those who are not familiar with the concept, how do you define a balance sheet recession?

A balance sheet recession typically happens after the bursting of a debt-financed bubble. In the bubble days, people leverage themselves up, and once the bubble bursts, liabilities remain, asset prices collapse and people realize their balance sheets are underwater. When that happens, people start repairing balance sheets by paying down debt or increasing savings, which is basically the same thing. That’s the right thing to do at the micro level: everyone in that situation has to get their financial house in order. But when everybody does it all at the same time, then we enter a massive fallacy of composition problem [in other words, while individuals are correct to save and pay down debt, if everyone does this at the same time it hurts the economy by lowering consumption]. If someone is saving or paying down debt, you’ve got to have someone on the other side borrowing and spending money. But when a debt-financed asset bubble collapses, everybody could be paying down debt and no one is borrowing money, even at zero per cent interest rates. In that case, all the savings that are generated and all the debt that’s repaid comes into the financial sector but won’t be able to leave the financial sector. That becomes the leakage to the income stream. And this can happen even with zero interest rates.

What leads you to think Canada has the ingredients for falling into a balance sheet recession?

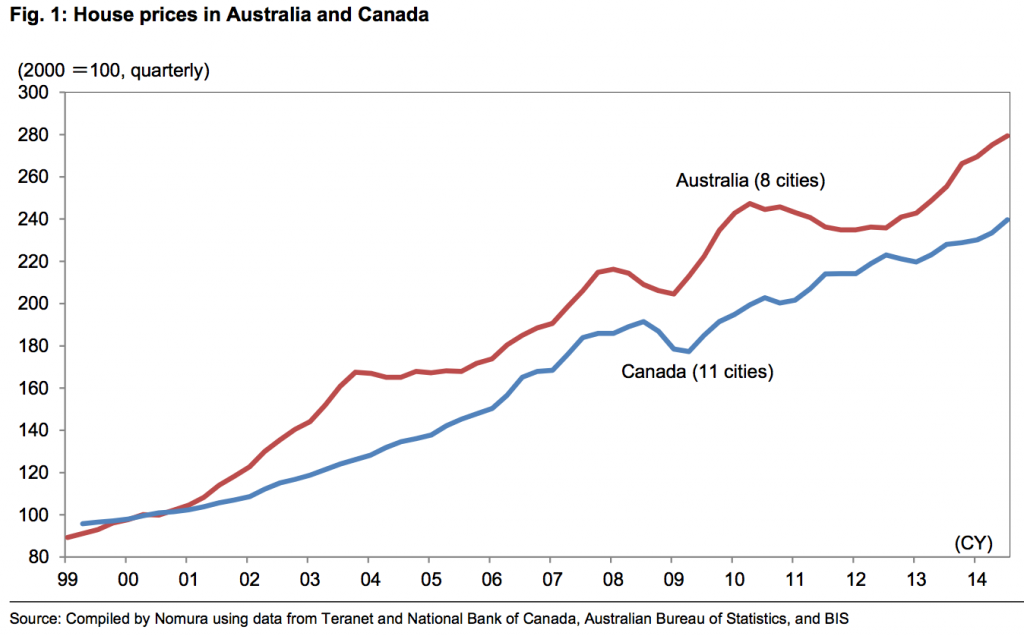

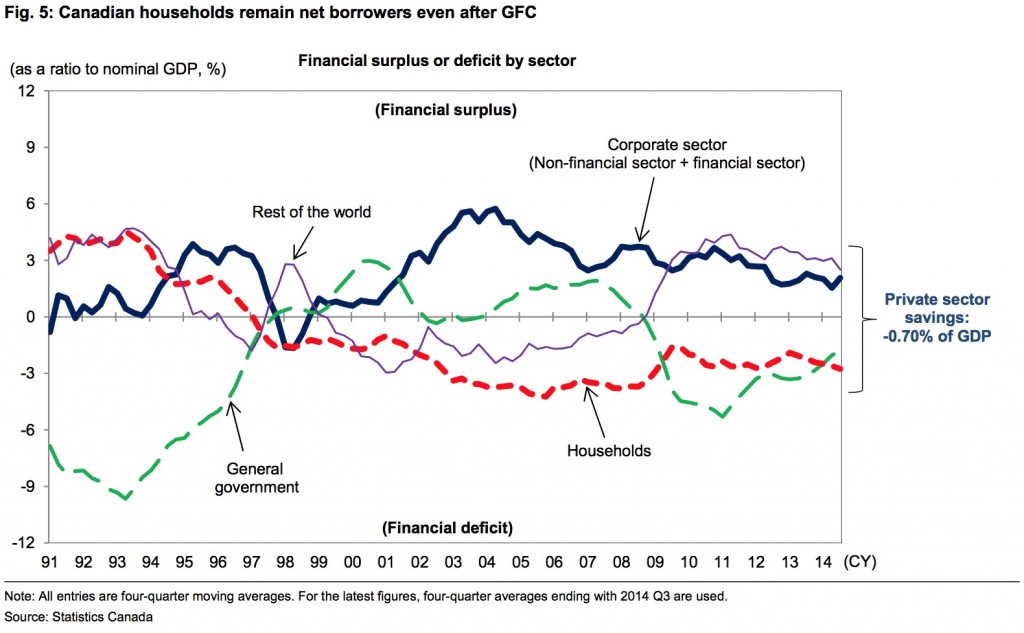

Your house prices have gone up quite steadily even after the Lehman shock. Since 1997, Canadian households have been in deficit all these years. And that means a huge buildup of debt over this period. Now as long as house prices are rising faster than your debt levels, balance sheets will still look fine for individual households. But if something should happen to house prices, if they should start falling, then suddenly some of the people who bought these houses realize their balance sheets are underwater. And if they all start paying down debt or increasing savings, Canada could fall into a balance sheet recession.

Your house prices have gone up quite steadily even after the Lehman shock. Since 1997, Canadian households have been in deficit all these years. And that means a huge buildup of debt over this period. Now as long as house prices are rising faster than your debt levels, balance sheets will still look fine for individual households. But if something should happen to house prices, if they should start falling, then suddenly some of the people who bought these houses realize their balance sheets are underwater. And if they all start paying down debt or increasing savings, Canada could fall into a balance sheet recession.

How does Canada compare to Japan before its bubble burst?

In the Japanese case it was the corporate sector that went crazy during the bubble days. The household sector was very conservative, didn’t borrow very much, but the corporate sector borrowed massively. It was the corporate debt repayment that sunk the Japanese economy even with zero per cent interest rates. In the Canadian case it’s the reverse. Canadian companies don’t borrow that much. In fact, over these years Canadian companies actually saved money and it was the household sector that borrowed money … so there are differences like that. But the fact that one group, one major group of the economy has been borrowing money on ever-rising asset prices, the house prices, is a cause for worry. At the moment, everything is making sense, but if something should happen to house prices, all the problems that accumulated over the years may suddenly come to the surface with the debt levels.

Do you think the authorities in Canada should enact fiscal stimulus now, or wait until consumers are deleveraging?

I don’t think you’d get much support if you put in fiscal stimulus now. The words “fiscal stimulus” [have] such a bad connotation from earlier days … pork-barrel politics, wasted spending, all that kind of stuff. And so until people really feel that something has to be done, you won’t get much political support. If you have limited political capital you don’t want to waste it too early. But I think politicians can explain to people that this is what has to be done once we get into that stage.

In your recent piece, you advise the authorities in Canada and Australia to use macroprudential regulation to ensure that the household sector and financial system can withstand a decline in house prices. What specifically can they do? Should they burst the bubble, even at this late stage?

I think they can do things like [make] sure that the loan-to-value ratios are kept at conservative levels and make sure that households really have income to … pay down [their] mortgage even with some shocks to the economy.

A lot of those policies might actually cause the bubble to burst. A cynic might say that politically they don’t want to bring forward the pain.

I’m sure that’s a big concern for the actual elected leaders. But the central bank can still do quite a bit on the financial regulation side, [such as] slightly more stringent requirement for allowing mortgages and so forth, which hopefully will not attract too much public attention. But who knows, it may be too late already.

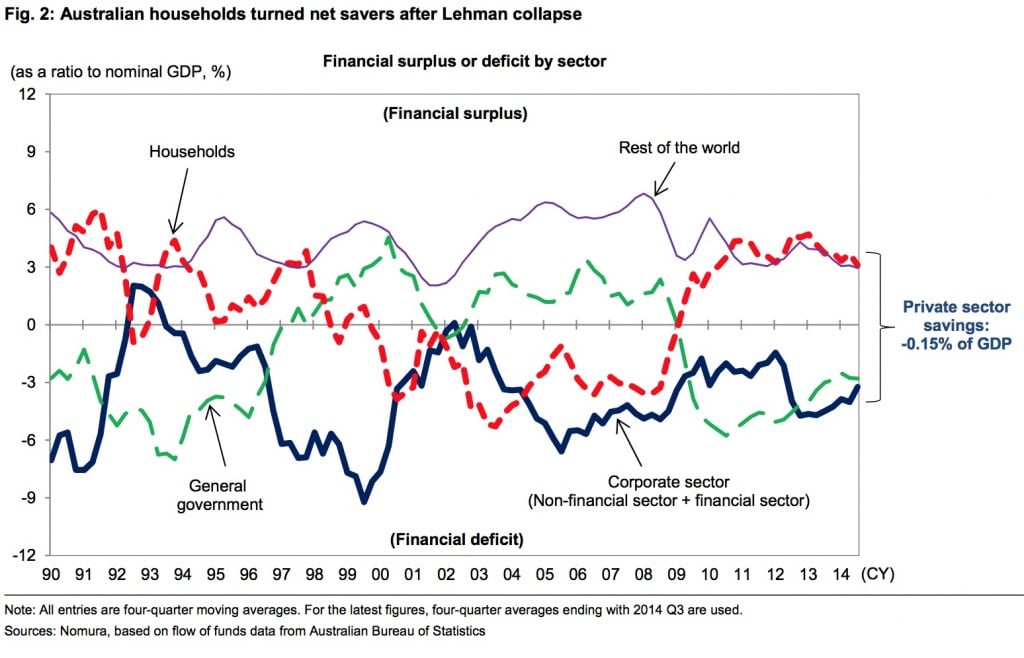

Australian households started saving after the financial crisis but Canadian households kept borrowing. What might explain this divergence?

Maybe they thought Australian house prices were already too high at that point and some people got scared.

They seem like they’re very similar economies.

When I saw those Canadian and Australian charts I was very surprised, too, that Canadian households kept on borrowing money when Australian households reacted somewhat close to households all around the world after the Lehman crisis.

Having seen how Japan handled its recession, what should Canada do differently if it falls into the same situation?

I would suggest that [Prime Minister Stephen Harper] explain what disease Canadians have, that individually everyone in the private sector is doing the right thing. Collectively, you are destroying the economy because if someone is paying down debt or increasing savings someone else needs to borrow money and spend. And the government will play that role as someone outside the fallacy of composition and they will maintain the fiscal stimulus as long as necessary until the private sector is ready to borrow.

Andrew Hepburn is a freelance journalist and former hedge fund researcher. He writes on commodities, the stock market and the financial industry. Follow him on Twitter:@hepburn_andrew