The Kijiji economy and what it says about Canadian households

A report from Kijiji about Canada’s booming second-hand marketplace offers a look at how struggling families make ends meet

Share

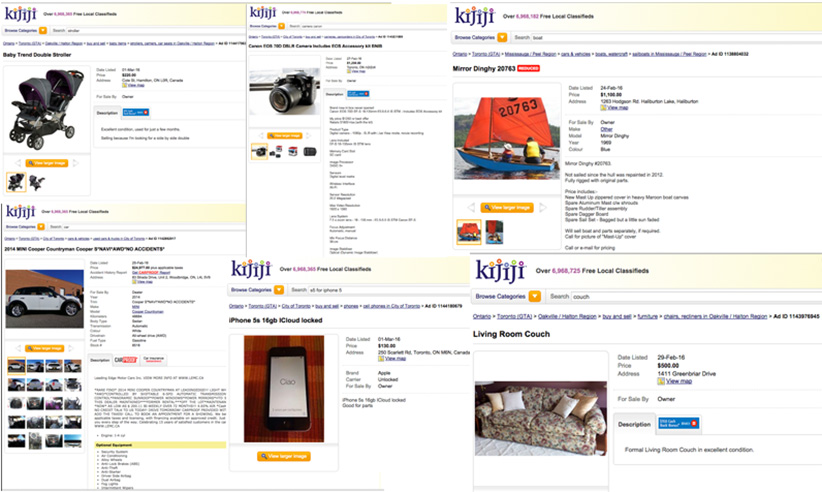

Kijiji released their second annual report on the second-hand economy today. Yes, that Kijiji—the site where maybe you looked to find that second-hand smartphone or sold off your baby stroller when your child was too big for it. As with last year’s report, Kijiji has partnered with an impressive team of academics to field a survey of our habits of trading, renting, donating, buying and selling “previously loved” goods.

The second-hand economy isn’t new. Thrift stores, garage sales and church basement sales have been around for a very long time. Family members and neighbours were swapping, re-gifting and borrowing each other’s belonging for centuries before the term “sharing economy” gained traction. But I think there are at least two reasons to pay more attention to a report like this one.

First, the emergence of online platforms to facilitate trades in second-hand goods is a game-changer in all kinds of ways.

Digital classified services like Kijiji (or Craigslist) should make it easier for resellers to set prices and for buyers to shop around, reducing information asymmetries and improving efficiency in matching buyers and resellers. Interestingly, the report finds that resellers who take the time to use online information before posting their own ad do better—earning an average of $579 from online classifieds versus $279 for resellers who estimate their price. It’s possible that resellers of more expensive goods are just more likely to take the time to research their pricing. The data in this report don’t tell us.

Online platforms may also now be really important for the off-line second-hand economy. Check your local Kijiji or Craigslist or other online classifieds and you’ll see lists of notices for garage sales, book sales and more. One community organization in my city now relies on an online form to pre-screen donations of household goods for Syrian refugees. A popular local chain that resells baby clothing, toys and gear on consignment relies on a web-based platform for resellers to check their list of goods for sale and track their profits. Moving online, in theory, makes it easier for the local book sale to attract more buyers and to attract buyers from outside the area volunteers could reach with posters or flyers. Again, this should be good from the standpoint of connecting buyers and resellers in a competitive market, even if the transaction itself takes place off-line.

Kijiji is a bit like Uber, but for second-hand strollers and cellphones. And, as the research report makes clear, there’s up to $36 billion in economic activity happening that wouldn’t without marketplaces for second-hand goods that 85 per cent of us in Canada participate in at least once a year. But we don’t yet know much about the distribution of all that activity. The report has a few tables on the geography of survey respondents who were intense second-hand buyers or resellers. It could be a fun project to track trends in second-hand economic activity against other measures of local or regional economic activity, and hopefully next year’s report might do some of that.

Which brings me to my second reason for thinking this report and the topic of second-hand markets more generally are worth some attention: I think we might learn something new about how Canadian households manage their personal finances and make ends meet.

The report includes three composite profiles of high-, medium- and low-intensity users of second-hand markets. The “heavy” user likely has kids and a comfortable household income. He or she may be selling goods the household no longer needs or upgrading from an older-model good (maybe last year’s smartphone model) to subsidize the costs of the new model in the traditional retail market. The report points out that while many second-hand buyers or resellers name ecological motives, economic motives are strongest and 22 per cent of resellers said their proceeds would be going toward the cost of a new product.

But the profile that interests me the most is the“medium-intensity” user whom the report describes as struggling to make ends meet with an income that “barely meets their budgets.” I’ve seen this kind of user in other data. They struggle at times to keep up with monthly bills. They are more likely to turn to fringe “financial services” like a payday lender or pawnbroker. They may have some small cash savings, but if a sudden cost wipes those out, their next buffer is fixed assets like household goods. They aren’t less financially literate than you or me, and in fact do a better job of watching their spending and economizing. How do they use the second-hand economy to liquidate fixed assets as a way to borrow or to meet household needs at a lower cost? What role does the second-hand market play in their household financial practices? I think these are big and policy-relevant questions worth asking.

A few years ago, we all had some fun with a federal minister using Kijiji ad information to supplement official labour-force statistics. That probably wasn’t a great use of Kijiji data. This report is far more promising and deserving of the attention of policy-makers.