What happens when Canada’s housing bubble pops?

If it’s any consolation, we won’t be going down by ourselves

Nathan Denette/The Canadian Press

Share

A few days ago, Bank of Canada governor Mark Carney released another alarming, albeit muted, warning shot about the state of the Canadian real estate market. Some properties in Canada are “probably overvalued,” the central banker said during an interview with CTV. Last week Finance Minister Jim Flaherty hinted he is also worried about housing: “We watch the housing market carefully and we are prepared to intervene if necessary,” he said.

So, are we literally living in a bubble? And when it bursts, will it get as ugly as it did south of the border? Here’s where the most recent speculation is pointing:

Yes, we’re in a bubble, and it will probably pop soon.

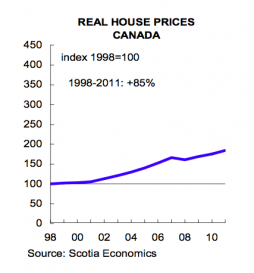

The signs of a bubble are unequivocal. At 13 years and counting, Canada’s current housing boom is one of the longest-lasting in the world, the Bank of Nova Scotia noted in a recent report. The real price of Canadian homes has increased by 85 per cent on average since 1998. Prices stagnated in 2008, at the height of the financial crisis, but they were back on the rise again as soon as 2009, when they grew by nearly 20 per cent, according to the Canadian Real Estate Association.

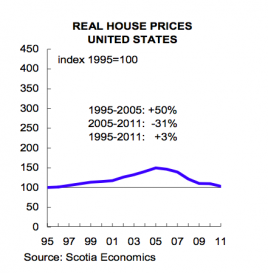

Meanwhile, Canadian household debt set a new record last year. On average, the debt burden of Canadian families stands at 153 per cent of their disposable income, according to Statistics Canada. That’s almost as much debt as American households had at the peak of their bubble.

The ratio of home prices to rents reflects returns that people can expect from homeownership–in terms of either rents earned by landlords or saved by owner-occupiers. Based on this measure, The Economist figures the Canadian market is overvalued by over 70 per cent. Last month, Merrill Lynch wrote in a report that our housing market is afflicted by “overvaluation, speculation and over supply.” No wonder a recent international survey of housing affordability found Vancouver to be the second-least affordable city in the world!

The scary part is that, by most accounts, 2012 is going to be the year when housing prices start heading south. The housing market is already showing signs of weakness. Despite a rebound in December, housing starts fell in the last quarter of 2011. And in some smaller markets on the west coast, condo prices have already declined 15 per cent, according to Merrill Lynch. The bank predicts that prices nationwide will slip by five per cent this year in the best-case scenario. A spike in unemployment could trigger a 10 per cent price drop.

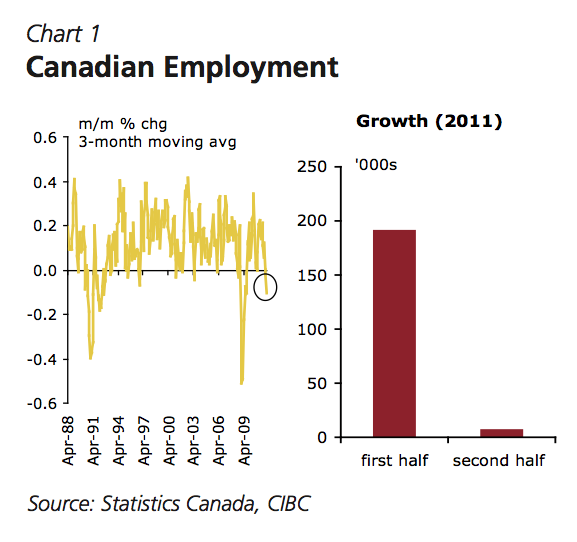

Meantime, the economy is slowing, unemployment has been on the rise since September and it will probably continue to climb as Ottawa reins in public spending. CIBC noted this week that job creation hasvirtually stalled in the second half of 2011, and a growing number of Canadians are resorting to self-employment, where they’re likely to earn 10-15 per cent less than full-time employees. “The job market is currently weaker than any non- recessionary period,” the bank noted. The reason this is frightening is that, even if uncertainty about the global economy forces the Bank of Canada to keep rates at current lows, Canadian households have no room to take on additional debt. Many will probably struggle to keep up with what they already owe.

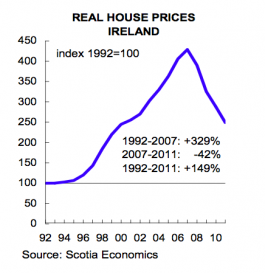

If it’s any consolation, we won’t be going down by ourselves. Canada’s pop will be part of a much bigger deflation of Western housing markets. The U.S., and Ireland were merely the beginning, says the Economist. The U.K. is getting there, and the next victims could include Australia, Belgium, France, New Zealand, Spain, Sweden–and, of course, us.

No, it won’t be “housemageddon.”

The good news is that, in all likelihood, our bubble won’t go KABOOM! Instead, we seem to be in for a painful but not devastating pop. That’s because only certain parts of Canada are in a bubble. Overcrowded markets in B.C. and Ontario may be close to busting, but many other areas of the country remain very affordable. The very same survey that ranked Vancouver most-unaffordable-city after Hong Kong rates Canada the third most affordable country, after the U.S. and Ireland.

Secondly, even in areas where there is a bubble, not all sectors of the market are equally inflated. Concerns about overvaluation and oversupply mostly regard the condo market, which has been the main engine driving the boom. Construction of single-family homes, on the other hand, “has already landed softly below its long-run average,” Merrill Lynch notes.

Most importantly, however, Canada’s pop won’t bring down the entire financial system, as it did in the U.S. That’s primarily because subprime mortgages are virtually non-existent in Canada, and government guarantees on mortgage insurance act as a buffer protecting the banking sector from housing market downturns. A whopping 75 per cent of mortgages in Canada are fully insured by Ottawa, according to the Financial Stability Board. Also, at the height of the crisis, the U.S. was grappling with severe unemployment, which kept fuelling the housing bust as more and more households became unable to afford mortgage payments. Though job creation is softening in Canada, there’s little reason to believe joblessness will rise to America’s level. Even economist Nouriel Roubini–famously dubbed Dr. Doom for accurately predicting the great recession–doesn’t think Canada is headed for disaster. He predicts a 10-per cent correction, but not a U.S. style meltdown.

Besides, Ottawa is keeping a close eye on the market. The government already cut the maximum length on federally insured mortgages from 35 to 30 years in early 2011, and Flaherty may have more of the same in mind–along with other cooling measures that aren’t tied to interest rates.

Most likely, then, the Canadian market will let the air out gradually. As inelegant as that sounds, it’s good news.