Why a $15 minimum wage is good for business

Boost the minimum wage and you boost the economy from the bottom up, writes economist Armine Yalnizyan. That means more demand for what businesses have to sell.

(iStock)

Share

This week the Ontario government introduced plans for truly sweeping labour reforms. Perhaps none is more important—and controversial—than the proposal to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour by Jan. 2, 2019.

There’s an argument to be made that going so far so fast could kill the goose that lays the golden egg, destroying jobs at a time when more are desperately needed, particularly for the young. The counterargument is that this would add another gold-egg-laying goose to the mix, and spur the demand that creates jobs in the first place.

Unsqueeze the driver of growth

Domestic consumption drives the economy, in Canada and around the world.

Household purchases account for 57 per cent of Canadian GDP, a rising share of economic activity since the Great Recession of 2008 because business-to-business purchases, business investment and exports haven’t found their mojo since.

Housing costs have been rising in the biggest cities where most of the population lives. That is eating up even more disposable income, constraining how much of the monthly budget is left to make purchases from domestic and international producers.

When higher income households see wage gains, some of it goes to savings. Additional consumption also often flows to vacations and luxury goods, often imported. In other words a non-trivial part leaks out of the local economy.

When lower income households see a sustained rise in incomes, they spend virtually all of it. Most goes to food (more nutritious food or eating out), better health care and more education. Sometimes it also goes to rent (moving to a better neighbourhood). Almost all of this spending stays in the local economy.

So boost the minimum wage and you boost the economy from the bottom up.

Spur productivity

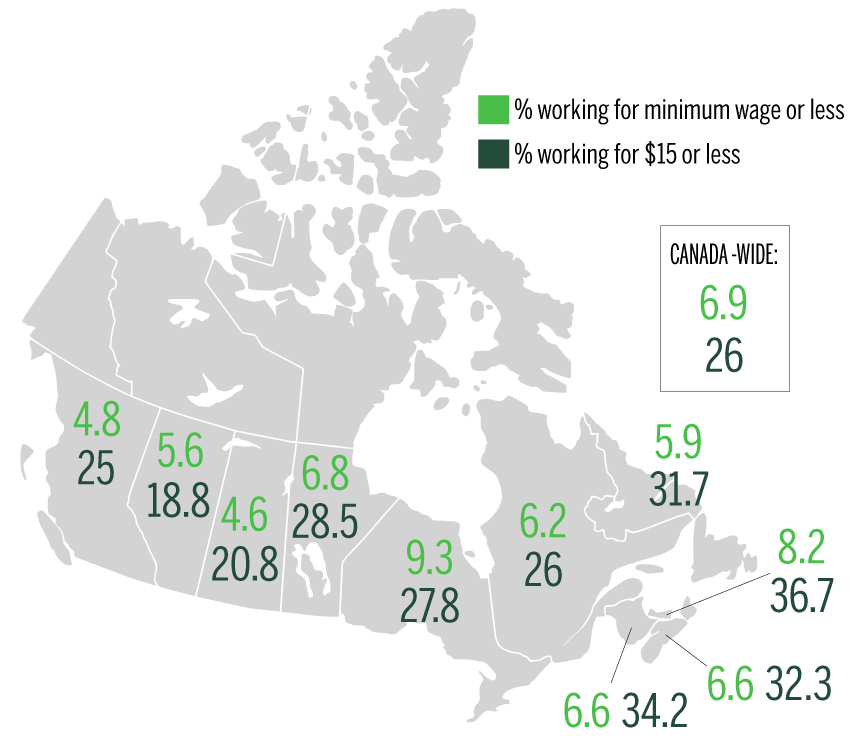

You may be surprised to learn nearly 30 percent of Ontario’s labour market earned less than $15 an hour in 2016. The nation’s biggest labour market has more people working at low wages than any other big economic engine of Canada (Quebec, B.C., Alberta)

While some workers may lose their job after the minimum wage increase (more on that in a minute), a very large number of workers will see an important pay hike, and that will loop back into the economy. Increased consumer spending will grow the top line of businesses, and increase the need for more workers to meet the higher demand for goods and services…and earning better pay.

Rising costs will also raise productivity, something virtually every business and economist says we want and need.

That’s harder to do if you’re doing things the way you’ve always done them.

Canada has been running a low-wage economy for decades, relatively speaking, according to Statistics Canada. In fact, at last count Canada outpaced the U.S. in the reliance on low-wage work. Within Canada, Ontario has the highest reliance on low-wage work.

Boosting wages may knock out some jobs and some marginal businesses. The remaining enterprises that rely on low-wage work will see improved productivity, less absenteeism and turnover, reducing recruitment and training costs.

We shouldn’t rue the loss of a few poorly paid jobs, particularly when rising minimum wages also help meet the twin challenges of the early 21st century: constrained revenue growth and higher service needs due to population aging.

We’ve got to spur change, and a substantially higher minimum wage will surely spur change.

Job loss and (teen) angst

Economic theory offers a perfectly reasonable assumption: a higher minimum wage leads to job loss. Theory has not been borne out by evidence, with one possible exception: teenagers.

Let’s take this in two steps: research on job loss, and teen troubles.

A 2016 study examining 78 years of federal minimum wage hikes in the U.S. (between 1938 and 2009) showed no correlation between those increases and job losses, even in sectors most affected by such policies.

Between 2013 and 2014, 13 states increased the minimum wage. The majority of these states saw above-average job growth.

A review of studies suggests even where the impact of minimum wage increases is not “benign,” job loss evidence has to be weighed against what happens to the purchasing power of the remaining workers.

The point is, even where there are job losses, other opportunities open up, and there is more purchasing power to spur demand.

Furthermore, higher minimum wages improve not just the top line, but the bottom line of business. Exhibit A: Walmart, which last summer reported higher than expected profits, partly due—according to the company—to paying its workers higher wages.

But what about the kids? A paper written for the Ontario government in 2007, and widely cited of late, says a “10 per cent increase in the minimum wage is likely to reduce the employment of teens by three per cent to six percent.”

This is a serious issue. Though their unemployment rate has been very slowly falling, young Canadians (15 to 24) are the only demographic group who have seen their employment rate remain far below pre-crisis levels. This means there are more young people simply out of the labour force. A growing group of idle young men has never produced a happy turn of events.

But minimum wage policies are not the only worry young workers face. Their unemployment rates go up even when the inflation-adjusted value of minimum wage declines, because macroeconomics swamps all. Any reduction in demand will mean last hired is first fired. That means young people and newcomers always have higher unemployment rates, no matter the level of the minimum wage.

The new normal?

A more nagging problem is that “failure to launch” has led to more people in their prime earning years working minimum wage jobs.

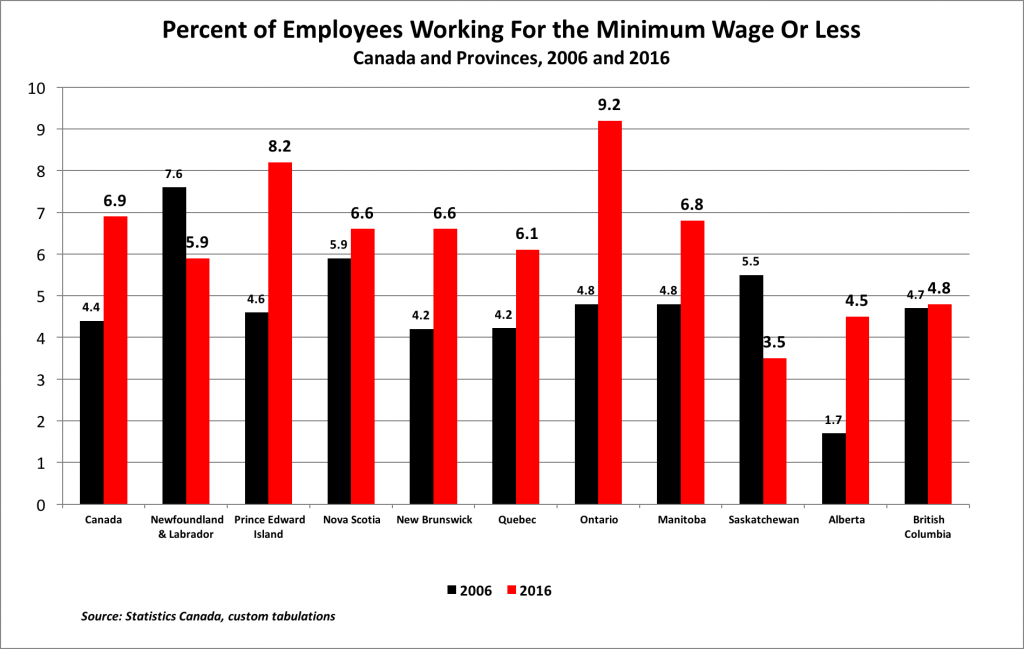

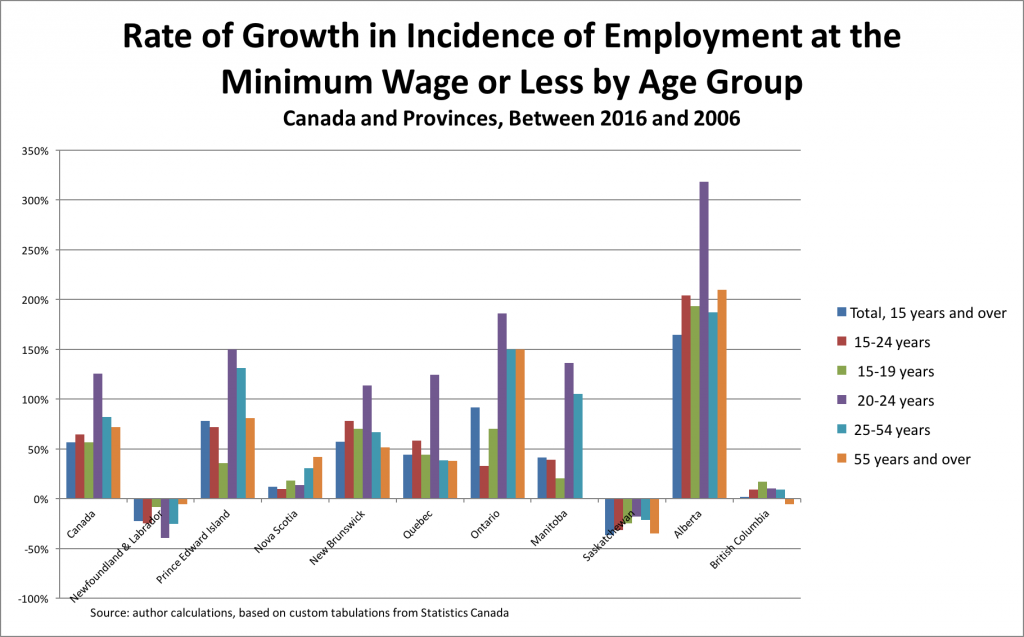

In Canada, the proportion of people aged 20 to 24 working a minimum wage job doubled since pre-recession, as did the proportion of people aged 25 to 54. The proportion of older workers (55+) working minimum wage jobs grew much more slowly…but it’s the fastest growing age cohort of workers.

(Click charts to enlarge)

The fact is, a higher proportion of teenagers work at a minimum wage job in most provinces across Canada today than a decade ago (49 per cent across Canada, 70 per cent in Ontario in 2016), but a growing proportion of adults have been doing so as well.

(Click to enlarge)

In 2016, 64 per cent of minimum wage workers across Canada were not teenagers, up from 52 per cent in 2006. In Ontario, the proportion of minimum wage workers who are not teenagers has risen from 45 per cent to 61 per cent in a decade.

When do we start to be concerned about the macroeconomic effects of so many workers having to wait for a law to change before they get a pay hike? Have you ever tried to change a law?

In the 1950s and 1960s, the manufacturing sector provided a growing share of middle class job opportunities, thanks to strong unions. In the 1970s and 1980s, growth of the public sector (and its organization) accomplished the same.

It’s unclear where the next middle class will come from, but until we figure that out, it should be clear why people are raising the roof about raising the wage floor. It may only be one tool to help low-wage earners—others include reforms introduced this week by the Province of Ontario, more affordable housing and child care, and more ways to pursue collective action—but it’s a big one.

Why is $15 the magic number?

Most people agree that today’s $11.40 an hour minimum wage in Ontario is too low to make ends meet, unless you can depend on others’ incomes.

But why is $15 an hour the “right” amount for a minimum wage in Ontario? Why not $30 or $100 an hour?

There is no articulated policy reason for the $15 minimum wage, but there could and should be.

Some say it should be enough to lift someone out of poverty if they work full time and full year. Historically, however, minimum wage wasn’t about poverty reduction. It was about acknowledging the inter-relationship of all work, and making sure no one got left too far behind as wages grew.

In many European countries public policy sets the minimum wage in relation to other workers’ wages, at between 50 per cent and 60 per cent of the average wage.

Today the average hourly wage in Ontario is $26.43.

Half of the average is $13.22; 60 per cent is $15.86

The government’s proposal to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour by January 2019 will bring it to roughly 55 per cent of the average wage, if wage growth keep pace with inflation in the intervening period.

Once you have reached the target level, annual inflation adjustments should take care of increases; but the level should be reviewed every five years, in case things are getting out of whack.

This makes the process rooted in logic, and predictable, both of which rightfully improve business buy-in.

By the way, there is no legislated minimum wage in Sweden, Finland, Norway, Denmark, Switzerland, Iceland and Italy.

The reason? Collective bargaining covers all workers, and minimum pay in these agreements is most commonly between 60 and 70 per cent of average wage rates.

Still think $15 is too rich? The negotiated minimum in Denmark is the equivalent of C$22.50. The legislated minimum in Australia is C$17.70.

Both countries pay their lowest-skilled workers much more than we do, but have unemployment rates similar to Ontario’s, around six per cent.

The elephant in the room: big business

Raising the minimum wage raises costs for business, there is no denying; and the affected businesses are not just small business.

Businesses large and small have been making the case that they can’t afford paying more for labour going back to when laws were first proposed to curb the use of seven year-olds in coal mines or put an end to 16-hour workdays.

Of course, there will be some job losses, and some smaller businesses that go under. There are always some marginal businesses for whom any higher cost—electricity or any other input, a legal dispute—will mean The End. That is genuinely heart-breaking for that business.

But small business isn’t the only beneficiary of minimum wage laws.

Low wages help maximize profits. Period.

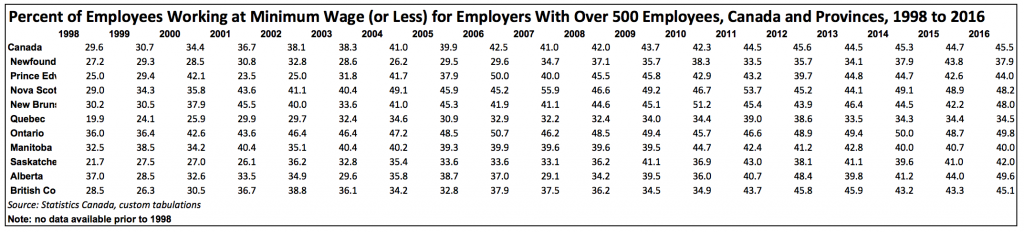

Did you know at least half of all minimum wage workers in Ontario work for employers with over 500 employees? That’s a growing trend. The same is true in most other provinces.

(Click to enlarge)

It’s unclear why governments need to protect corporations, but not the workers they hire.

And it’s also unclear why businesses (and many economists) bemoan the increase in minimum wage but are mum about ballooning compensation of employees at the top, from senior management to the CEO. After all, these are also rising input costs. That should also trigger concerns about prices, employment levels and solvency, n’est-ce pas?

Businesses will understandably worry that uncertainty from south of the border may make all of this more challenging to implement. Let’s pause on the fact that Ontario’s economy is expected to enjoy the fastest growth in Canada in 2017.

But it’s true. The future is uncertain.

What’s not uncertain: the slow drip of unresponsive labour market regulations and mostly unenforced rules over the past quarter century has shifted bargaining power towards employers, against workers.

That was just challenged in Ontario. And not a moment too soon.

Armine Yalnizyan is a Toronto-based economist and business commentator. You can follow her on twitter @ArmineYalnizyan

The author wishes to thank the team at Statistics Canada for the timely production of these custom tabulations. Statistics Canada is back!