Why do the Liberals insist on projecting a deficit for this year?

Economist Stephen Gordon has studied Ottawa’s finances and sees a surplus for 2015-16. Are the Liberals playing ‘silly games’ with their deficit talk?

Minister of Finance Bill Morneau participates in a town hall meeting ahead of pre-budget consultations in Ottawa, Monday February 22, 2016. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Adrian Wyld

Share

Although it attracted most of the attention given to the Liberals’ pre-budget update, the projected deficit of $18.4 billion for the upcoming fiscal year 2016-17 is largely of academic interest: it represents the Liberals’ version of what would happen if they simply carried out the plans set out in the April 2015 budget brought in by the Conservatives. One suspects that the Conservatives’ version of what 2016-17 would bring would look very different: perhaps without that $6-billion “risk adjustment” or the $4 billion of additional spending. But it doesn’t really matter—no-one is going to implement the Conservatives’ plan for 2016-17. What puzzles me is what the Liberals are saying about what’s going on now.

The Conservatives’ plan for the current fiscal year is still in place, and the new Liberal government is still projecting a deficit of $2.3 billion for 2015-16. This is slightly more optimistic than the $3 billion they projected in last November’s fiscal update, but I still can’t figure out how that’s going to happen. (See here for my doubts about that November forecast, as well as an update here.)

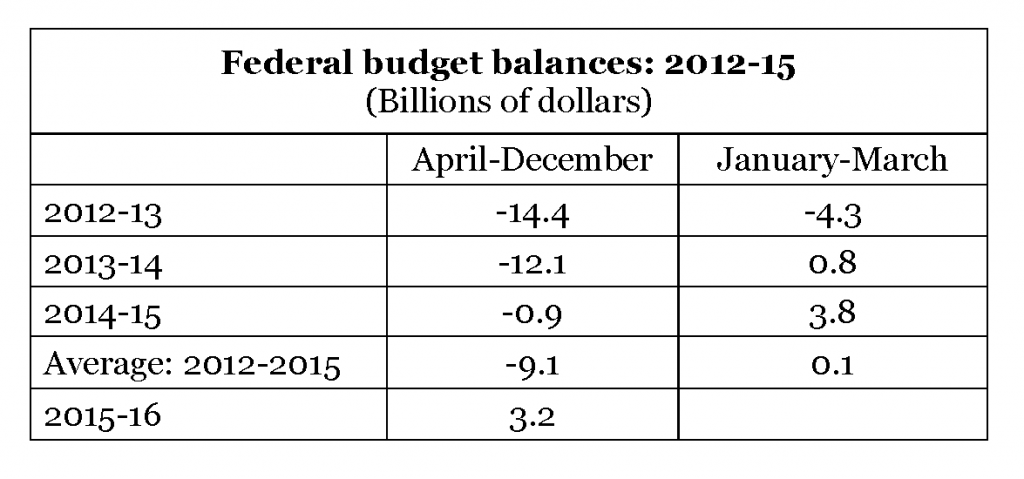

The December Fiscal Monitor was released along with the update, and it shows a surplus of $3.2 billion over the first nine months (April-December) of 2015-16. How do we get from a $3.2-billion surplus in the first nine months to a $2.3-billion deficit over the entire year?

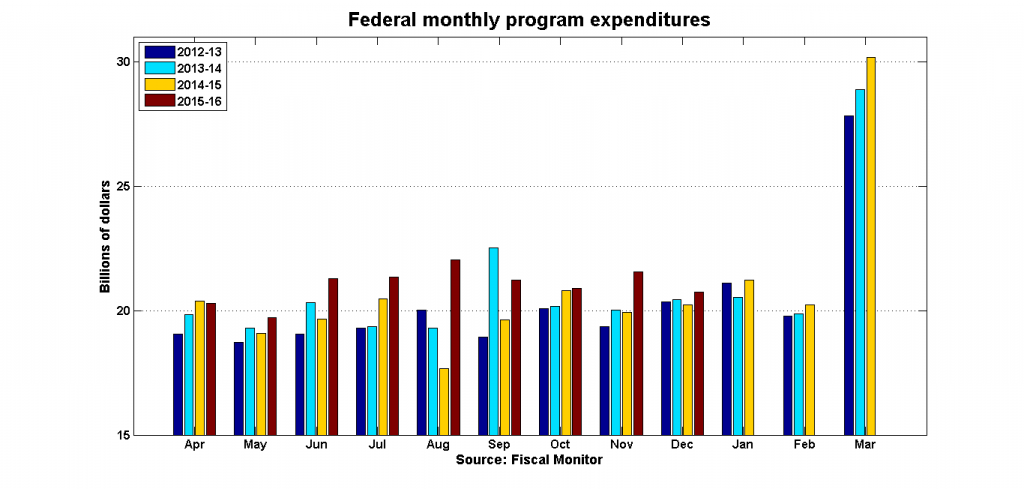

Finance Minister Bill Morneau’s answer to that question is that a lot of bills will come due in March, and there’s something to that. Program expenditures are fairly stable from month to month throughout the fiscal year, but there’s always a sharp spike in March :

But this isn’t really enough of an answer. Last year saw the same pattern in expenditures, but the federal government ran a $3.8-billion surplus in the final three months of 2014-15. It would take a $7-billion swing from last year’s January-March balance to send the federal government into deficit this year, and a $9.3-billion swing to bring it down to the Liberals’ projection.

I suppose this is still possible, and people will no doubt point to the downward revisions to the economic outlook. But the economy wasn’t exactly booming in the first three months of 2015: real GDP fell 0.7 per cent at annual rates, and nominal GDP—which is what matters for revenues—fell by 3.5 per cent at annual rates. That’s a pretty low bar.

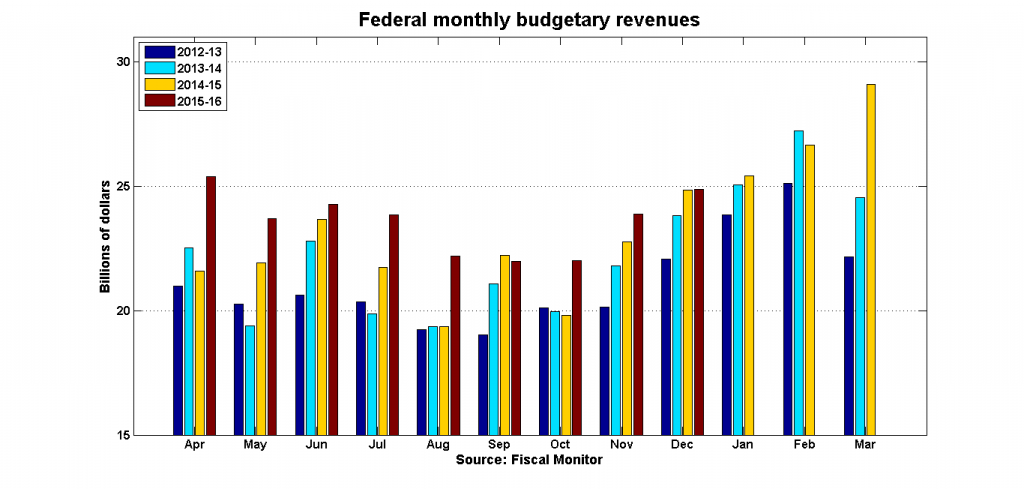

While it is true that we can expect an end-of-year spike in program expenditures, we can also expect a surge in revenues in January and February if the usual patterns hold:

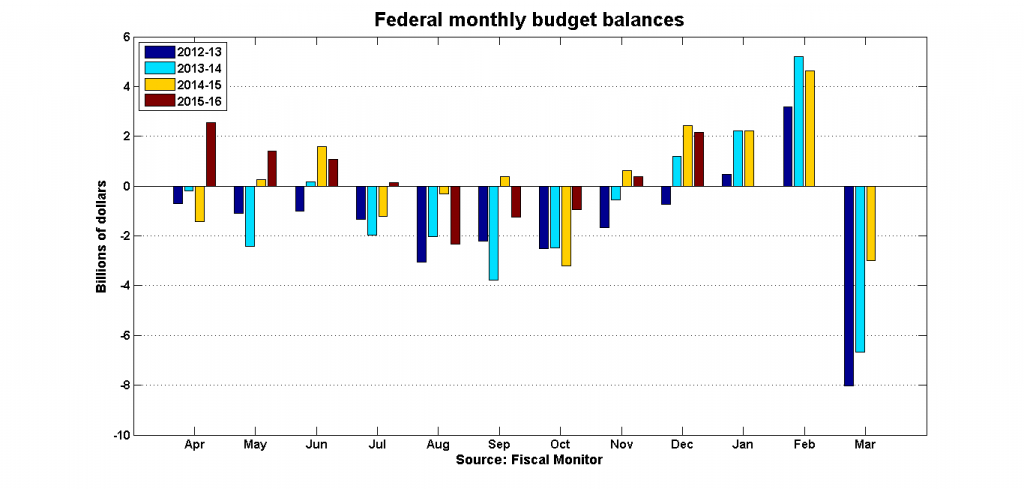

When you put the two together (including debt service payments), you get a seasonal cycle for monthly budget balances that looks like this:

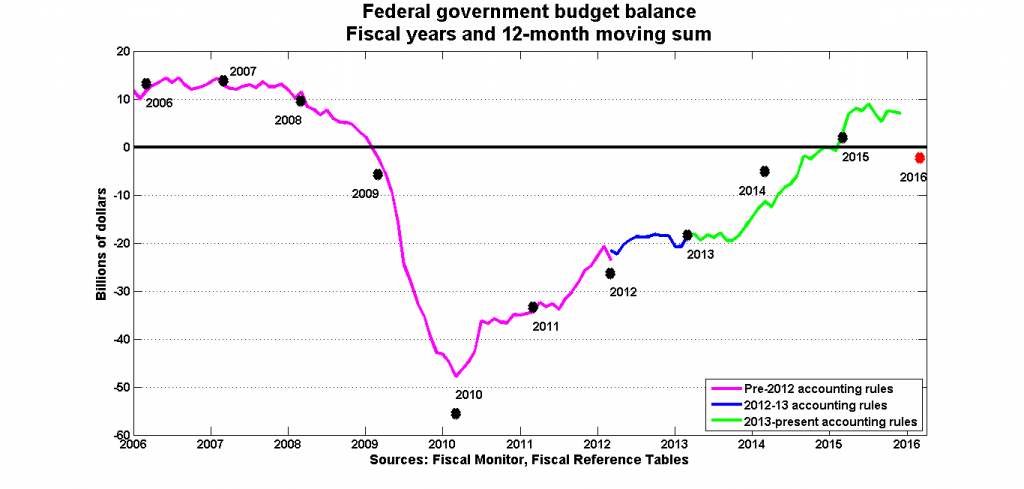

These seasonal patterns are why I like to work with 12-month moving sums for Fiscal Monitor data: each observation includes data for all 12 months, and always includes the most recent March. As of December 2015, the 12-month sum of the budget balances showed a surplus of $7 billion:

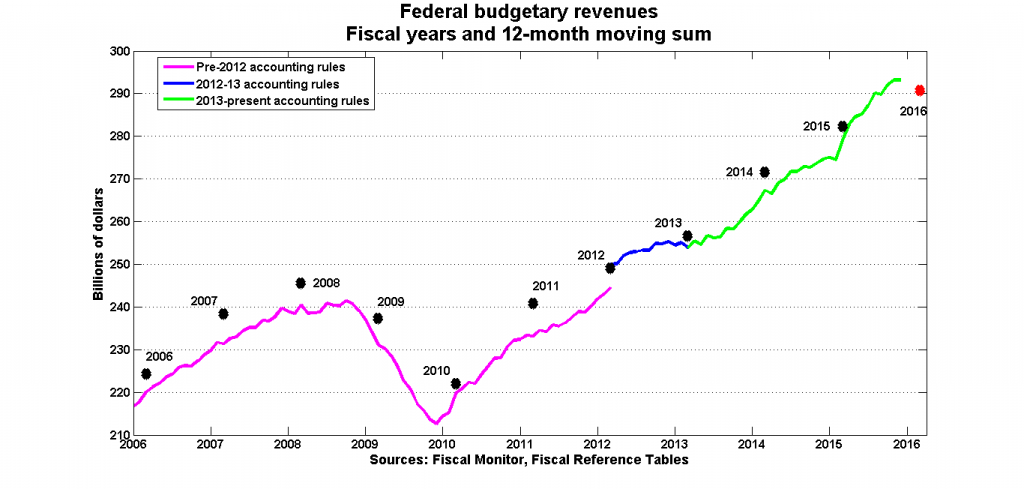

The story here is that revenues are coming in well ahead of what the Liberals are projecting:

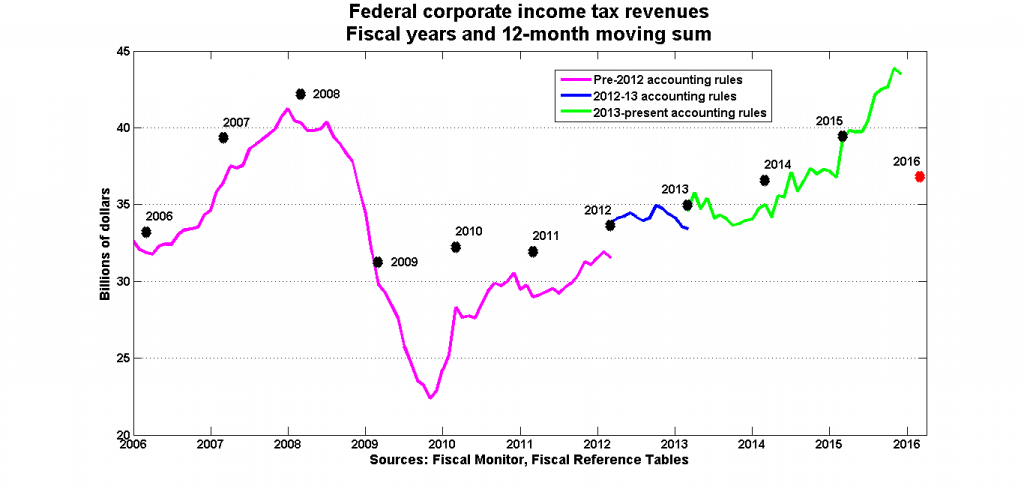

And in particular, it appears to be corporate income tax (CIT) revenues that are surprising on the up side:

This surge in CIT revenues is puzzling. While I think the weakness in the Canadian economy has been exaggerated at times, it’s hard to see how the slow growth we’ve seen can be reconciled with a sharp increase in CIT revenues. And then there’s the question of how and why CIT revenues are supposed to fall off a cliff in the next few months.

An official at the Department of Finance offered a two-part explanation during a recent conversation. The first part was new to me, and would explain why CIT revenues have increased rapidly in an environment of weak economic growth. A few years ago—a cursory search suggests the 2010 budget—the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) was given extra resources to crack down on tax evasion and some of the more aggressive forms of tax avoidance, and these efforts are finally bearing fruit. This year’s CIT revenues have been boosted by a few biggish court-ordered payments that have resulted from various investigations and audits. Finance doesn’t know if these supplemental payments will be repeated; they depend on the outcomes of proceedings that are under way. But this does offer a very plausible explanation for why CIT revenues have been so strong.

The other part offers an explanation for why the government is expecting corporate income taxes to come in lower than what the latest trends suggest. This is a story I had heard already, and has been mentioned in the past two Fiscal Monitors. Corporations pay their income taxes in instalments throughout the year, and these instalments are based on profits earned in the previous year. Firms that are doing less well this year than during 2014-15 are probably paying too much in income tax, and government revenues will fall as these overpayments are repaid. In other words, the weak economy hasn’t yet shown up in CIT instalments, but it will show up in the end-of-year reckoning.

I’m not convinced. As many observers have noted, it seems very unlikely that corporations will docilely continue to make large tax instalment payments as their financial situation deteriorates. It’s far more likely that they will reduce or even stop those payments altogether, and I’m given to understand that the CRA is typically very accommodating when this sort of situation arises. For example, look at the pattern of CIT revenues in 2008-9 as the financial crisis hit. Even though firms were presumably still faced with instalment payments based on the booming economy of 2007-8, the decline in CIT revenues coincides almost exactly with the decline in economic activity.

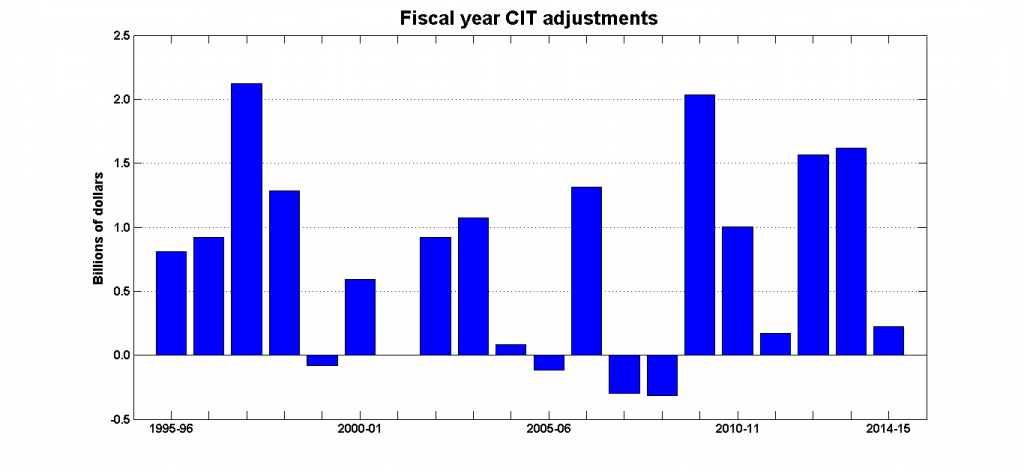

It’s still possible that there will be a large, negative year-end adjustment to CIT revenues this year, but such a revision would be something new. This chart compares the CIT revenues reported in the March Fiscal Monitor over the 12 months of the fiscal year and the annual CIT revenues reported in the Fiscal Reference Tables. (Changes in accounting rules are taken into account by comparing the March 12-month numbers with the annual data released in the following autumn under the same rules used to produce the March figures.)

Negative revisions to annual CIT revenues are rare, and large negative revisions have never happened in the 20 years for which data are available. It might happen this year, but it would be a development that has no recent precedent.

Kevin Page is already concerned that that Liberals are showing signs of not being able to clear the (very low) bar that the Conservatives had set for transparency in public finances. A budget balance a couple of billion dollars on one side of zero or the other is of almost no real importance in the grand scheme of things, but the Liberals’ apparent willingness to play silly games here is a worrying sign.