How the deficit gambit stunned Conservatives into silence

Conservatives took for granted that they had won the intellectual debate about deficits. So when the Liberal party made its surprising tack left during the campaign, Conservatives simply didn’t have the words.

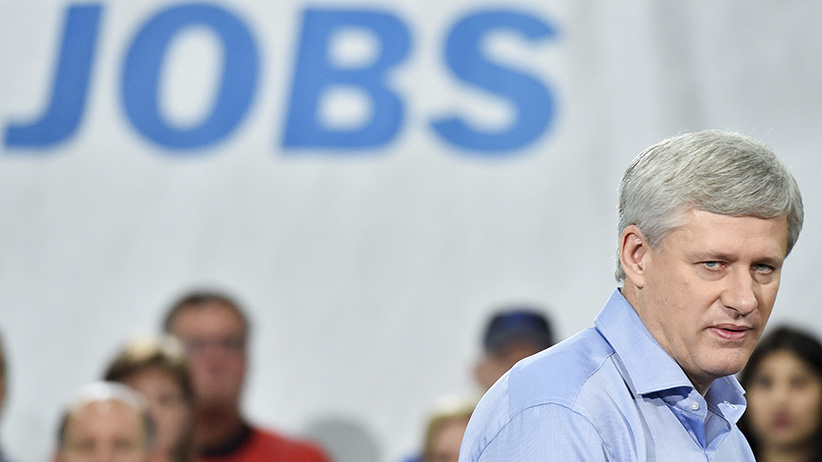

Conservative Leader Stephen Harper speaks during a campaign stop at Global Systems Emissions Inc., in Whitby, Ont., on Tuesday, October 6, 2015. (Nathan Denette/CP)

Share

Earlier this month Canadians went to the polls to select a government and a Prime Minister. It was the first federal election in more than twenty years contested on fiscal policy and conservatives lost. The result ought to prompt a moment of introspection and rediscovery.

The post-election analysis thus far has tended to characterize the election as a referendum on Prime Minister Harper. That is to be partly expected. Mr. Harper governed Canada for nearly a decade and, despite a significant record of accomplishment, was always seen as an imposter by the country’s left-wing commentariat. Justin Trudeau ran a “time for a change” campaign that resonated with Canadian voters and delivered a majority government.

Yet the public clamour for newness needed to be weighed against Prime Minister Harper’s record of accomplishment and the backward-looking ideas proposed by the winning Liberal Party and their dauphin leader. And herein lies the lesson for conservatives as they develop a forward-looking agenda.

Prime Minister Harper’s record is one of competent, effective, and conservative governance. He limited the scope and ambition of the national government consistent with his view of federalism and the role of the state relative to the individual and civil society. He reoriented federal support programs to give families more choice over their child care decisions and personal savings, resisted calls for “national strategies” and centralized bureaucracy to address every perceived social and economic problem. He cut taxes – including sales taxes and corporate taxes – and brought federal revenues as a share of GDP to their lowest level in fifty years. And he controlled public spending. Federal spending grew, on average, by 0.2 percent per year since 2011. The budget is balanced. And Canada’s debt-to-GDP ratio is significantly lower than all other G7 countries. Polls near the end of the campaign indicated broad support for his economic and fiscal record.

When one adds Prime Minister Harper’s principled foreign policy and ambitious free trade agenda, a picture of conservative leadership comes squarely into focus. He admitted his imperfections during the campaign, but, like Isiaah Berlin’s hedgehog, Mr. Harper understood the big issues well, and consistently got them right.

But it was more than just Mr. Harper’s governing record on trial in this campaign. The election was also about a conservative policy consensus to which he had contributed – some may say forged – for over a quarter century.

The Reform Party was established in 1987, and Mr. Harper was the founding policy chief. That party led the charge for fiscal probity at the federal level and elected a significant contingent of Parliamentarians, including Harper, in 1993. Canada’s federal government had run budgetary deficits for more than a quarter century to that point. But fiscal profligacy was not the exclusive domain of the federal government. Several provinces followed a similar course of high taxes and large, protracted deficits. Then the country hit a wall. The federal debt-to-GDP ratio hit nearly 70 percent. Federal debt charges as a share of revenue exceeded 30 percent. The Mexican peso crisis of early 1995 brought things to a head culminating in the Wall Street Journal editorial warning that Canada was becoming “an honourary member of the Third World.”

Out of this crisis came reform. Mr. Harper, as an opposition member of Parliament, was a leading voice for fiscal consolidation. But it would be wrong to characterize this moment as a partisan one. Mainstream politicians across the political spectrum understood the urgency and adopted serious programmes of fiscal reform. There was a pervasive consensus that swept across the country. As one think-tank scholar has put it: “The entire political class decided to stop treating this as a matter of political contention and started treating it as a matter of national interest.”

This consensus helped to put the country’s public finances on a solid footing. Total government spending fell from 53 percent of GDP in 1992 to 39 percent in 2007. The federal debt-to-GDP ratio shrank from 68 percent in 1996 to 28 percent in 2009. And the federal tax burden began to fall as successive governments reduced taxes. The result was period of sustained economic growth, job creation, and wage increases.

The political outcome was a durable consensus in favour of balanced budgets. The federal government ran eleven consecutive fiscal surpluses until the 2008-09 recession. Provincial governments, by and large, did the same.

Fast forward to the 2015 federal campaign. The winning Liberal Party – the party that had delivered a balanced budget at the federal level the last time it held office – broke from this political orthodoxy. The Liberals rejected the balanced budget that Mr. Harper had delivered and campaigned on an explicit promise to return to deficit during a period of economic growth. Mr. Trudeau called deficits “a way of measuring the kind of growth and the kind of success that a government is actually able to create.”

This assertion – backed up by a plan to add $150 billion in new spending to the federal budget over four years and at least three years of deficit spending – signaled a major break from the fiscal policy orthodoxy that dominated national politics in Canada since the mid-1990s. The Liberals were promising, nay campaigning on, a pledge to break the balanced budget consensus. As David Frum has written of the Liberal electoral proposition: “The government he [Mr. Trudeau] leads will repudiate the legacy not only of the incumbent Conservative prime minister, Stephen Harper, but the neoliberal Liberals of the 1990s.”

Liberals abandoned the consensus and sought to re-litigate a debate that been largely absent from mainstream federal politics for twenty years and conservatives, to be frank, were not ready for it. The conservative intellectual case for balanced budgets had atrophied. We lacked the political vocabulary to make the case for prudent government spending and a balanced budget to the Canadian public. Mr. Trudeau’s calls for “investment” seemed more compelling than our musings about “being in the black.” We were unable to persuasively argue for the concrete, real-life utility of not spending more than the government collects. A return to deficit spending, the anti-consensus, won the day.

Why? Canadians did not become fiscally irresponsible overnight. Nor did they suddenly abandon the prevailing consensus and assume a new ideological poise in favour of deficit spending and bigger government. The result has more to do with conservatives’s inability, or perhaps unreadiness, to communicate the case for balanced budgets and fiscal probity. We took for granted that we won this intellectual conflict. We assumed that Canadians instinctively understood the importance of fiscal plans that reconciled.

It is a powerful reminder that conservatives cannot take for granted the intellectual terrain gained in past battles.

And this is the lesson: While conservatives must put forward concrete, practical, forward-looking ideas to grow the economy and help families make ends meet, we must never lose sight of our rearguard and continue to make arguments in favour of sound public finances and balanced budgets. The conservative consensus was, it turns out, not as durable as we assumed.

Conservatives must continue to demonstrate how a balanced budget is an important means to the ends of lowering taxes and creating the conditions for economic growth and job creation. We must explain how a limited, less activist government promotes individual choice and creates the space for community and civil action. And we must argue that going backwards to failed ideas of the past would undermine the economic and fiscal gains that we have made. In short, it means following Samuel Johnson’s adage about how “men more frequently require to be reminded than informed.”

Yet, despite losing this battle, Canadian conservatives are well positioned for the longer struggle. We have plenty of reasons to feel optimistic and have made tremendous progress in the battle of ideas. Mr. Harper will go down as a historic Prime Minister and the most important conservative in Canada’s modern political history. We must follow his example to put forward thoughtful, well-crafted ideas that speak to the goals and aspirations of families. But we must also never take for granted that past battles will not re-emerge as skirmishes that must be refought. We must always keep up rearguard actions to protect what we have won. Conservatives would be wise to heed this lesson.

Sean Speer and Ken Boessenkool have been senior policy advisors to Prime Minister Harper and were members of the Conservative national campaign team.