Learning to fight the opioid crisis at Vancouver Community College

If you’re going to be an addictions counsellor, book learning isn’t enough. These students are getting a dose of reality

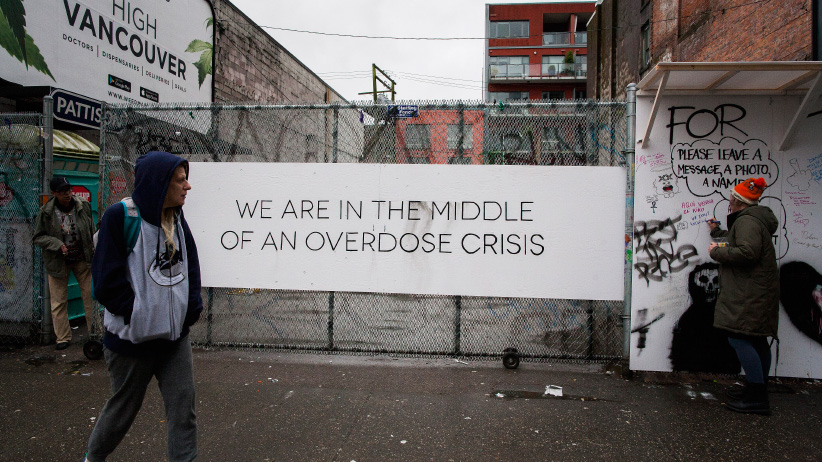

A memorial wall dedicated to overdose victims in Vancouver’s Downtown, British Columbia, Monday, April 10, 2017. April 14, 2017 marks the one year anniversary since Medical health officer Dr. Perry Kendall declared a Public Health Emergency in response to another surge in drug-related overdoses and deaths. (Rafal Gerszak)

Share

A lot of dark, rocky years passed before Jeremyah Clark figured out what he truly wanted to do with his life: what his own experiences and predilections would make him good at. It turns out he is good at helping people—specifically, those struggling with drug addictions.

After all, the 29-year-old Comox, B.C., resident has a kind of expertise, stretching back to childhood. “I was addicted to mainly cocaine,” he recounts. “It became opiates in the end. I was using various forms of pills . . . Oxys and Percocets and that kind of stuff . . . did that for, well, my whole life.”

In 2013, Clark—who has been sober for the past five years—ended up in a psych ward at Richmond Hospital for two weeks, then a detox centre for another 10 days or so. When he left the facility, he sought counselling through an organization called Transitions. He began working as a support and outreach worker with the Turning Point Recovery Society, which provides residential support services to recovering addicts. “That was the job that changed my life,” says Clark. Admitting he’d been self-centred until that point, “it switched me from thinking about myself to thinking about others and giving back.”

That’s a drive motivating many of the students who register for the addiction counselling skills certificate program at Vancouver Community College (VCC), says program coordinator Matthew Stevenson. The average age of students in the program, a part of VCC’s continuing studies program, is 40. “A lot of them have been working for 20 or 30 years and they have decided they want to make a difference. Their passion is in helping people.”

VCC has offered an addiction counselling program since 1980. Over the years, reflecting the college’s growing emphasis on experiential learning, the program has evolved to give a greater dose of reality and practical learning to prospective counsellors. Clark graduated from the program last August and now works in Comox and Courtney with the Vancouver Island Health Authority in rehab support and other positions. Even with his personal experience and his work at Turning Point over the past few years, Clark benefited from both the theoretical and experiential facets of the VCC certificate program.

“Getting the basic knowledge . . . allowed me to connect with the clientele I was working with,” says Clark. The VCC program, aside from teaching him how to tap into the resources available to addicts, gave him interpersonal communication skills and helped him set aside his own emotions. With that, he explains, walls can come down between clients and support workers. “When you build that relationship with them and they begin to trust you, the things that you can do for them—and the things they can do for themselves—just grows exponentially. It’s cool to see.”

The “experiential” learning at VCC comes in a number of forms, explains Bhupie Dulay, an instructor in the program. Some students in the program come in and share their own experiences with personal or family addiction issues. Experienced counsellors—not to mention recovering addicts—also discuss addiction issues with students. Students build counselling skills together; not through what one might call role-playing, but rather, explains Dulay, through more “genuine and authentic” conversations that help build skills transferable to counselling.

Then, students do fieldwork. They observe and participate first-hand in support work with organizations such as Peak House, a live-in program for youth with substance abuse issues. The students, says Matthew Stevenson, “are not necessarily going to Hastings Street [the Vancouver neighbourhood infamous for a disproportionate number of drug addicts] and seeing that face to face. But they will work with our practicum coordinator to find a suitable practicum site. That could be anywhere in the Vancouver area that does have a focus on addiction.”

Vancouver, more so than most Canadian cities, is in the grip of an opioid crisis, with the city expecting to surpass 400 drug-related deaths by the end of 2017. That crisis, says Stevenson, appears to have triggered an uptick in the number of people registering for VCC’s addiction counselling certificate program. Social services work, he says, is now one of the top five growing areas of employment in greater Vancouver. But not everyone is cut out for the job. Before entering the certificate program, applicants must take a prerequisite basic counselling skills course to see if they have the aptitude—the emotional endurance—to cope with such work.

For Jeremyah Clark, who still works in more of a support role, the VCC program has been a big step toward his goal of becoming a full-fledged drug addiction counsellor. It was never a role he envisioned himself doing. “For me, five years ago, life was horrible. I wasn’t even a human being. I cared solely for myself.” Now Clark gets calls from former clients thanking him and saying they’ve cleaned up and life is wonderful. “And I’ve started to see myself as a positive influence.”

MORE ABOUT COLLEGES:

- How to decide between college and university in Canada

- Crane training at this Alberta college leads to an uplifting career

- How Loyalist College is helping with a massive nuclear clean up

- Take that, Ikea! The Canadian college training world-class woodworkers

- Meet the Red River College students who found jobs by busting dust

- Fighting radicalism with research

- Drinking in class is encouraged at this Canadian college program

- Colleges promise to meld Indigenous learning into programming