Can Canada’s universities survive COVID?

Fewer international students, half-full residences, shuttered food services and empty parking lots add up to devastating revenue losses. And public funding has fallen over the past decade. Universities are in for a reckoning.

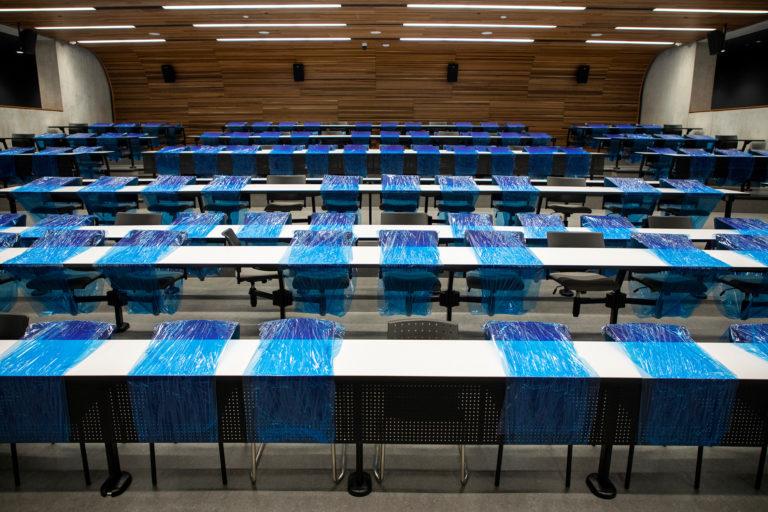

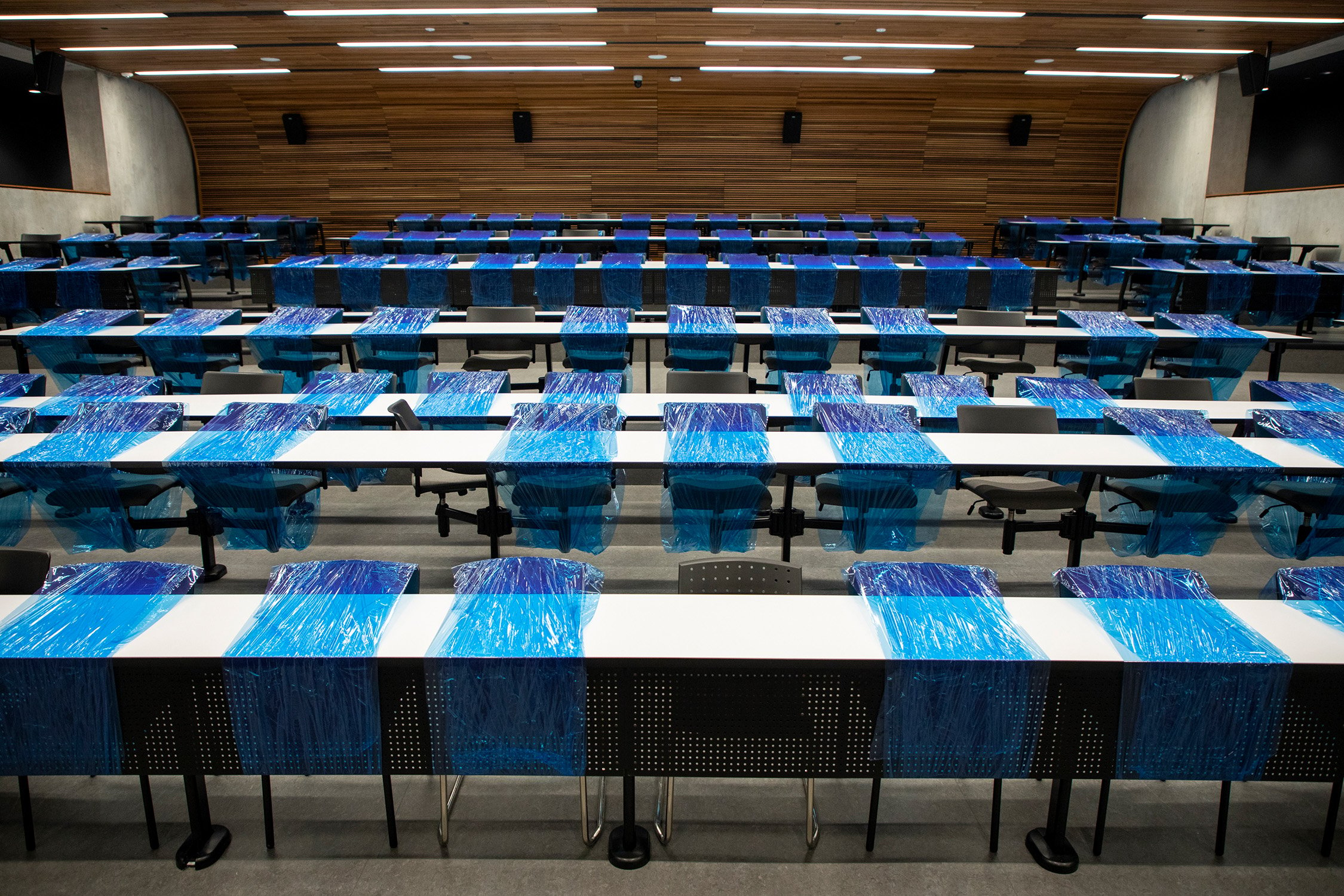

Building and classroom safety measures in the Maanjiwe Nendamowinan building at the UofT Mississauga Campus (Nick Iwanyshyn/University of Toronto)

Share

In early August, McGill provost Christopher Manfredi took the bus from Westmount to the school’s downtown Montreal campus. He actually got a seat for the 20-minute ride in, which is usually a feat to be celebrated. But on this day, it was a reminder that we’re still in a pandemic, and most people aren’t going into the office. Upon arrival at the school, campus looked much nicer than usual, says Manfredi. The lower field, an expanse of grass on the east side of campus, was glowing green, for example. In years prior it was dead by June, after thousands of graduates stomped on it excitedly on their convocation day.

Entering campus magnified the impact of COVID-19, says Manfredi. “We have to answer a set of questions—whether we have any symptoms, whether we travelled outside the country, whether we have been in contact with someone who has COVID-19.”

Along with screening, there are Plexiglas barriers and signage reminding people to wear masks indoors, measures that make up a fraction of the financial toll the pandemic has taken on the school. More significant are the multiple losses the university has incurred on its balance sheet, signs of which are also evident throughout campus: empty parking lots, shuttered food counters and closed athletic centres, not to mention residences that will only be at half-capacity in the fall. At the same time, the lights need to be kept on, the grass needs to be mowed and, eventually, the snow will need to be plowed. “I liken it to a heart attack versus chronic high blood pressure,” says Manfredi. “The heart attack requires instantaneous intervention to prevent the damage, but high blood pressure requires constant monitoring. We’re in the chronic high blood pressure stage of this.”

The ongoing public health crisis has thrown Canadian universities into financial uncertainty. The schools’ two main revenue sources—public grants and tuition fees—threaten to shrink as students opt for gap years and governments rein in spending. Supplemental income—from parking fees and corporate partnerships, for example—can no longer be counted on. Meanwhile, the recruitment of international students that many universities rely on to boost enrolments and revenue is clearly compromised. Despite taking swift measures such as hiring freezes and deferring already deferred maintenance, the country’s post-secondary schools have been struggling mightily since the pandemic hit. The University of British Columbia, for instance, is projecting a $138-million loss in tuition and is also anticipating a deficit for the first time—$225 million this upcoming academic year. Schools are pouring money into emergency measures with no sense of when or even whether a traditional post-secondary experience will resume. The pandemic piled on top of an already delicate situation raises an almost unthinkable question: will Canadian universities survive COVID-19?

***

Prior to the pandemic, many administrations were battling what higher education consultant Ken Snowdon called a “perfect storm” in a 2015 report for the Canadian Association of University Business Officers on the financial sustainability of universities. The 2008 financial crisis destabilized the schools’ business model—endowments, investments and public funding all struggled as a result of the downturn. When it was over, many other pressures continued to put a squeeze on the universities, including pension deficits, salary increases, pressing maintenance needs and the reality that the Canadian population was not going to produce massive increases in enrolment numbers any time soon.

And while Snowdon anticipated a financial rebound in a 2018 revision of his report, there remained persistent structural challenges. In particular, expenditures continued to mount, mostly as a result of salaries, which make up the largest part of operational spending. Recent data from Statistics Canada shows the continuation of this trend, with spending going up by $179 million from the 2016-17 to the 2017-18 academic year across the post-secondary sector, which spent over $16.7 billion on salaries alone in 2017-18. Salaries grew partly because the federal government eliminated a mandatory retirement age in Canada, and partly because an increased focus on research at several institutions meant faculty were teaching fewer hours, so more staff were needed. Other factors contributed to ballooning costs. Post-secondary education consultant Alex Usher has pointed to a rise in enrolment in programs like science and technology that cost more per student than arts programs, while government grants per student remain the same.

[contextly_sidebar id=”3fklSw96oXEJ9xamjy8rieiMy2sLid6x”]

In fact, in a 2019 report on the state of higher education in Canada, Usher described Canadian universities as having undergone a transition from being “publicly funded” to being “publicly aided,” as the gap between their expenditures and provincial grants steadily grew. While for decades post-secondary institutions received more than half their income from governments, the latest data from Statistics Canada shows a slight but steady decline, down to 47 per cent in 2017-18. The bulk of these funds come from provinces, supporting operating and capital costs, while federal funding often supports research.

Public funding peaked in 2010-11 at $22 billion, according to Usher, and dropped to $21 billion in 2016-17. Over a decade, Usher writes, the drop in provincial funding was about 15 per cent: “For the most part, these cuts have not been dramatic: in fact, the erosion of provincial funding has been rather quiet. A halt to construction programs here, a nominal freeze in operating grants there. But even in the absence of drama, over a decade these little nicks and cuts add up.”

The second-largest chunk of universities’ revenue comes from tuition—around 28 per cent across the post-secondary sector. But Canada’s low population growth means domestic enrolment, which peaked in 2013-14, can’t guarantee an institution’s financial health. This, in conjunction with regulations capping domestic tuition in many provinces, has meant that universities have looked to international enrolment to help make up the difference. In 2019-20, McGill’s international students comprised 30 per cent of the student body, and at the University of Toronto that number was close to 25 per cent. And across Canada, international enrolment made up 14.7 per cent of the student body in the 2017-18 academic year compared to 8.2 per cent in 2009-10, with most international students coming from China and Saudi Arabia. These students pay four or five times more than their Canadian counterparts, and sometimes much more than that—fees that are comparable, in some cases, to U.S. schools.

Snowdon describes international student enrolment as a “godsend to many institutions.” But he also sees it as a risky strategy, especially for schools that rely on it for more than half their tuition revenue. And it’s a strategy that has been highly criticized. “International students are constantly used as cash cows,” says Nicole Brayiannis, national deputy chairperson with the Canadian Federation of Students. “The only way this will change is by having that public investment that institutions currently aren’t receiving from the government.”

Given the fact that governments have been actively encouraging international enrolment at Canadian schools—in 2019, Ottawa announced a five-year, $148-million international education strategy, which included the goal of diversifying the countries students are recruited from—Snowdon thinks they have a responsibility to step in and help universities. “They were party to this,” he says.

***

Queen’s University Principal Patrick Deane laughs as he recalls the first week of the pandemic, when the administration’s focus was on ensuring there was hand sanitizer in every building. “Good lord, we had no idea what was ahead of us,” he says. Within a week, Queen’s had moved their operations online and sent most students living in residence home. “That was the simple part,” says Deane. “What came next was what the fall will look like. That has been very, very complex.”

According to a statement provided by the school, Queen’s is in a position to manage the shortfalls in the fall term and likely the one after that, but “beyond that, we would need to critically assess the financial situation.”

The pivot to online learning last spring meant universities needed to quickly invest in extra IT infrastructure and video call licences. Over the summer, many schools have made further investments in online learning. Queen’s expects to spend another $10 million on IT support, software to improve online learning and other expenses that support remote instruction. Deane feels strongly that these investments are critical, as painful as they may be to the bottom line. “We don’t want a Queen’s degree [earned during] COVID-19 to be a second-grade degree,” he says.

Certainly, students across the country feel they are getting a subpar product in online education. During the summer, Carleton undergraduate Jasmine Doobay-Joseph started a petition calling for Ontario to reduce tuition fees. “Students are paying to be able to sit in a classroom and listen to the professors face to face, to do labs that are not online [simulations], to be a part of discussion groups,” it reads. “We believe that students should only be paying full tuition for the full university and college experience.”

And it’s not just domestic students who are protesting the absence of rebates on tuition. Maya El-Hawary is a second-year international student at UBC in English literature and political science. She won’t be able to return to Canada in the fall, as the federal government has indicated it will not allow those with international study permits to enter unless they can prove they have to be in Canada to complete their studies.

El-Hawary is now living with her family in Dubai, which is 11 hours ahead of her scheduled classes in Vancouver. She misses going to office hours and having casual conversations with her peers. She was active in many campus clubs and longs to be in the library. “Let’s be honest, people don’t pay $40,000 a year just for the course material,” she says.

She understands why international students pay more than domestic students, but at a time when classes are delivered online, without the benefit of the social and professional capital, El-Hawary feels her higher tuition is a way for schools to make more money. “It creates a little bit of toxicity in your relationship to the school because you feel like you’re being exploited,” she says.

UBC, which has recruitment offices in New Delhi and Hong Kong, reports that it is seeing similar enrolment numbers of international students during COVID-19 to previous years—last year, 28 per cent of its students came from abroad. The school acknowledges the financial cushion this provides. “Thanks to the fees paid by international students, the university can employ more faculty members and provide additional supports and services to students across both our campuses,” reads a statement from director of university affairs Matthew Ramsey. He adds that international students enhance the experience for all students by bringing a “diversity of opinion, perspective and circumstance.”

Ancillary revenues are also a key source of income for schools. At McGill, for instance, funds from residences, food services and parking make up 15 per cent of total operating revenue. “That is going to be a big pressure point, for sure,” says Manfredi. At UBC, the “largest revenue loss” will be in student housing and associated services, according to Ramsey. At Queen’s, residences will be operating at about 40 per cent capacity in the fall, and the school has offered free parking since the pandemic started. It has also lost revenue from conferences and events usually held on campus over the summer.

Even as many schools report high enrolment numbers for September, universities won’t know final numbers until tuition is actually paid and the date for the deadline to drop courses rolls around; that could be as late as October. A drop in enrolment could impact how much government support a school receives; provinces like Ontario and Quebec provide funds based on enrolment numbers.

Across the country, government support to universities in the wake of the pandemic has been uneven. Quebec agreed to provide grants equivalent to 2018-19 enrolment numbers, providing the kind of backstop Snowdon suggests is needed right now. “That’s really taken the pressure off,” says Manfredi. The Ontario government provided $25 million to 45 colleges and universities “to help each institution address their most pressing needs,” and delayed the introduction of performance-based funding for two years; Alberta delayed a similar initiative by one year. Manitoba halted previously planned cuts and announced a $25.6-million fund that schools can access provided they show how they will meet labour market demands, deal with uncertain enrolment and deliver online learning. The Nova Scotia government has provided schools with their full operating grant upfront this year instead of in monthly instalments, and will go forward with a planned one per cent increase in funding. B.C. provided emergency funds for students when the pandemic hit, but did not offer any support to schools. And Ottawa instituted the Canada Emergency Student Benefit, which provided between $1,200 and $1,750 per month to students who were unable to work full-time over the summer and weren’t eligible for other income support.

***

The case for coming to the aid of this sector is compelling—there are over one million students enrolled in universities in Canada, post-secondary education makes up 2.4 per cent of the country’s GDP, and in some communities, universities fuel the local economy. “These students, our workforce, they are our future,” says Shiri Breznitz, an associate professor at the University of Toronto who studies the role of universities in regional economic development. Along with her colleague Daniel Munro, Breznitz wrote an op-ed for Policy Options in July, imploring governments not to cut post-secondary funding: “If we want higher education institutions to produce skilled graduates, support regional economic development and ensure education is accessible and equitable for all, we need to fund them in crisis and in prosperity.”

Snowdon takes it a step further, arguing that governments should put money into helping universities boost their talent pools. “From an institutional perspective, now’s a fabulous time to hire faculty because a lot of jurisdictions aren’t,” he says. “It’s a great time to snap up the very best and brightest.”

But given that some provinces haven’t even provided emergency funds to schools, an infusion of public cash looks unlikely. And other possibilities appear equally bleak. Raising tuition isn’t a viable solution—students are already balking at paying in-class rates for online learning. Corporate partnerships, mostly in research, are also hanging in the balance. “Everybody’s tightening their belts,” says Breznitz. ”This is not the time to say, ‘Somebody else is going to pick this up.’ ”

Snowdon predicts the short-term cash crunch will last two or three years. He says institutions must also look for longer-term solutions. He expects to see mergers, in the form of bigger schools absorbing smaller schools and collapsing administration costs, for instance, or institutions sharing delivery of more general first- and second-year courses.

One seemingly simple solution would be to increase enrolment—most teaching has moved online, so on-campus capacity is less of an issue. But larger classes require more faculty time—for grading and office hours—and any instructor will tell you that having a bigger class size decreases a course’s quality. Breznitz sees another issue with increasing enrolment, especially in the context of asynchronous online teaching: “When you post everything online and you don’t see the students and they do their work by themselves, then the question is, why would they come to you and not go to Harvard?”

Of course, not every student can get into an Ivy League school. But universities across the board may become more accessible if online class sizes expand. And in this sense, there is opportunity for all of them. “If you can ramp it up at a global level, or even a national level, the marginal cost starts to become much more attractive,” says Snowdon. “It’s one thing to be doing it for classes of 50, but if you start doing it for classes of 5,000, it starts to become financially much more viable.”

Only a handful of institutions—and particularly those with established international brands such as UBC, McGill and the University of Toronto—will be able to do that successfully, he says. “It’s going to be difficult for universities like Lakehead, the University of Winnipeg or the University of Regina to move into that league,” he says. “They don’t have the size, the investment capability or the brand recognition to move to national and international scales.”

For Deane, this type of scenario threatens to fundamentally transform the university experience. “Let’s say one result of this is that students decide online is not that bad and say, ‘I’d save money on residence—it’s cheaper I can just do it from home,’ ” he says. “What goes along with that is an increasing commodification of education as institutions insulate themselves against the damaging effects of that declining interest [in residence] by growing their online [enrolment].” The risk is that a university education becomes something you buy online rather than an immersive experience.

But Snowdon thinks that, in a way, the financial crunch the pandemic has caused is accelerating a conversation universities needed to have anyway. Schools have become so large, “you lose the notion of a community of learners or scholars,” he says. Universities have to some degree already shifted from being centres of learning to focusing on disciplines that will help students’ chances at employment. Snowdon thinks it’s worth asking: “What’s the cost of continual growth and greater emphasis on vocational programs that have a greater emphasis on jobs rather than learning?”

Snowdon suggests that refocusing on the role research plays in universities could help ground the vision of what a university should be and, on a more practical level, help schools focus on finding sustainable funding to support research. “There will be a reckoning in the next few years, and not only about the future of the institutions,” he says. “The institutions need to be asking themselves what they are trying to do.”

This article appears in print in the October 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Will they ever be back?” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.