How to save beer’s most important ingredient: Freezing it in time

Students at Saskatchewan Polytechnic teamed up with a local craft brewer to figure out a way to preserve their yeast

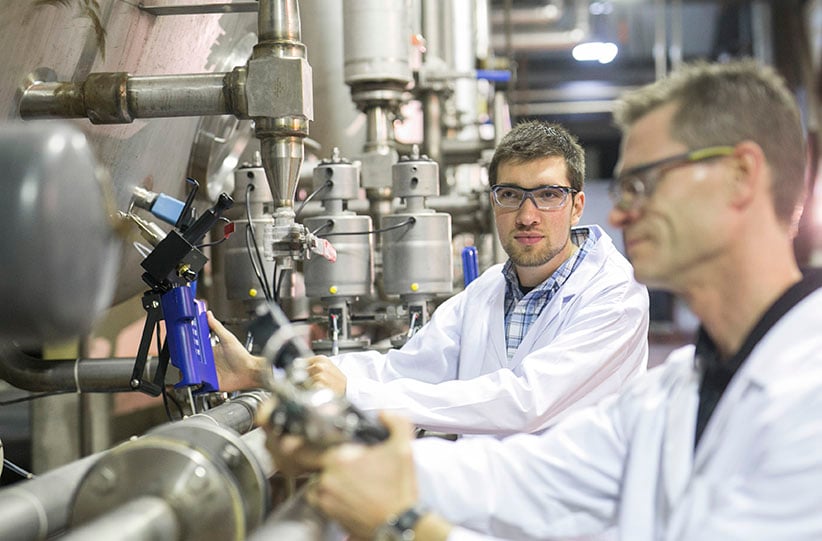

Lance Wall foreground, David Thiessen background. (David Stobbe/Saskatchewan Polytechnic)

Share

The study of booze isn’t limited to wine academies and chef schools. At Saskatchewan Polytechnic’s BioScience Technology Program in Saskatoon, researchers teamed up with a local craft brewer to find a way to preserve its yeast, the little single-cell organism that gorges on sugary liquids to produce alcohol and carbon dioxide. Why? Yeast is the brewer’s version of the colonel’s 11 herbs and spices or a baker’s mother dough, the key ingredient to the finished product’s recognizable taste and smell.

“Without yeast, you basically have barley soup,” says instructor Lance Wall. “There are different types of yeast and they all react in different ways, giving the brew its characteristics. For example, top-fermenting yeasts tend to float at the top of the fermentation, giving you an ale-type, fruity beer. Other yeasts that go to the bottom will give you a bolder lager type. It’s an art, really.”

Last spring, Saskatoon-based beer-makers at the Great Western Brewing Co. approached Wall, hoping to find a way to preserve their strain of yeast for safekeeping. “If a disaster happened at the brewery, you can repurchase other ingredients. But if you lose the unique yeast, it could be impossible to replace that,” says Wall.

Overseeing a team of two research students who looked at the brewer’s unique yeast strain, Wall recommended using cryopreservation, a process that essentially puts cells, tissues, bacteria, and in this case, fungi, in a state of suspended animation by keeping them in sub-zero temperatures.

It’s not a new technology, but that’s the goal of applied research: using existing science to find solutions to real-life conundrums—and preserving a good pint is arguably of utmost importance for a craft beer industry that is booming across the country. The lab also has a ongoing joint project with the University of Saskatchewan and Federated Co-operatives Limited (a distributor of products like lumber and propane) to look at the remediation of soil at former service station locations.

“That’s one of the unique things about our program: how broad the subjects we train our students in,” says Wall. “We also have students that go into food and agricultural production, pharmaceuticals, health and environment research. Part of the advantage for the companies is that any intellectual property goes back to them. We’re here to do the research, so they don’t have to worry about losing their data or investing in something that they’re not going to own.”

While this yeast challenge was the first official project Great Western Brewing Company had with the polytechnic, students have done one-month practicums with the company and many graduates have been hired. “We’re all after the same goal of training future workers,” says Wall, “ so we come together to have fun and solve these problems.”

[widgets_on_pages id=”Education”]