B.C.’s free textbooks plan needs a closer look

Prof. Pettigrew is skeptical

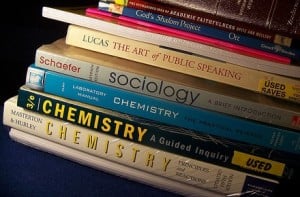

wohnai/Flickr

Share

This week, the B.C. government announced its plan to make free textbooks available to its students. This is one of those concoctions that smells delicious until you get a bit closer. And then it seems half baked. And then you realize it might even have been a recipe for disaster all along.

First, it is not at all clear who will be writing these books. None of the published reports I have seen make this point clear, and the government press release says they will be “created” with “input” from faculty and others. That sounds ominous. The only textbook that sounds worse than a free government textbook is a free government textbook created by a committee.

Even more ominous, none of the “quotes” in their press release is from an actual university instructor. Were faculty even consulted about this scheme?

Second, are these cobbled-together texts really going to be the best available texts? Almost certainly not. Conscientious profs may not, therefore, assign them in the first place. You can lead a prof to the web, but you can’t make her download. Besides, in a great many courses textbooks contain modern readings already themselves under copyright, especially in the humanities: think Modern Philosophy, for example. Such readings could not, I suspect, legally be included in an open source text. Which gives students yet another incentive to stop studying, say, Canadian Poetry. In fact, when I went to the web site of BCcampus, the group that will coordinate the this process, they directed me to a site with “good examples” of open textbooks. None of them were in humanities disciplines. With more digging, I did find an open-source art history “textbook,” but it was disappointing. When I clicked on a modern art section, for instance, I got an interesting, but rather casual chat on YouTube (favourite line in video: “This is a wild painting, really!). Interesting, no doubt, and even educational to an extent, but it’s not a textbook.

In any case, if profs do assign these books, chances are high that they will only be caving to student pressure to assign them because they are free. Which sounds fine until you realize that textbooks are different. The bureaucrats in Victoria may assume that a text is a text is a text, but anyone who has actually worked closely with such books knows better. Textbooks vary widely in their approach, content, and quality, and to imagine that one can be slapped together online and be good simply because it’s cheap is naïve.

Still further, the books are only free if you get the online version—which raises more questions. What, for instance, about courses where students need to have the texts in class to consult some key passage? Does that mean all students will need to purchase book readers or tablets to use them? Even if the cost of such items is recouped by the free books, such a scenario simply begs for more distracted students closing the textbook and opening Facebook.

If B.C. really wants to help students make ends meet, they could cut tuition by the 1,200 bucks or so that students are paying for real books. Now that would be sweet. It won’t happen of course, because few governments in this country are willing to spend more on education these days.

But in social policy, as in text books, you get what you pay for.

Todd Pettigrew is an Associate Professor in English at Cape Breton University.