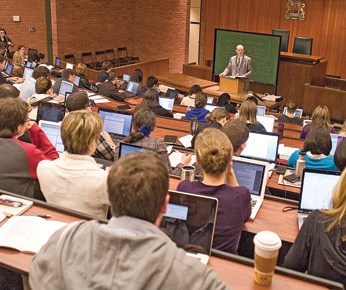

Moving from the small, intimate, setting of a high school classroom to a university lecture hall with hundreds of students can be intimidating. At first you may feel lost and nameless in the mob, and perhaps a bit awkward when raising your hand. In fact, the size of class might not matter all that much and a large classroom might even be to your advantage.

Moving from the small, intimate, setting of a high school classroom to a university lecture hall with hundreds of students can be intimidating. At first you may feel lost and nameless in the mob, and perhaps a bit awkward when raising your hand. In fact, the size of class might not matter all that much and a large classroom might even be to your advantage.

Tom Haffie, who teaches a first-year biology course at the University of Western Ontario, that has two sections of 700 students each, disagrees that smaller is always better. “It’s easier to have a more in-depth experience in a small class,” he admits. “But that’s all it is, it’s easier.”

Haffie, who is a 3M Teaching Fellow and describes his student evaluations as “average to above average,” relies heavily on technology to assist his students in getting the most out of his lectures. Notes are posted online beforehand, and audio is posted after class.

Each student is provided with a clicker, so when he poses a question, everyone has the chance to answer. When they do, Haffie can get a better idea of what was understood, and where students are having trouble. “It’s a way to have a kind of conversation . . . It’s a cliché that technology shrinks the room, but it’s true,” he says.

Students are still exposed to a small classroom experience. Similar to large classes everywhere, a small army of teaching assistants run labs and tutorials to groups of 40 students.

What really makes or breaks a large class like Haffie’s may have less to do with room shrinking technology, and everything to do with the professor’s performance as a lecturer. Emily Rodriquez, one of Haffie’s students, says he is “intriguing” and entertaining. “I want to go to that class. He lectures in a way that makes you want to learn biology,” she said.

A survey of 5,886 students conducted by consulting firm Higher Education Strategy Associates, and released in August, supports the notion that who is in front of the class matters more than its size. Participants were asked to rank nine factors that contributed to their favourite class. At the top of the list was “Interesting subject matter,” followed by “Instructor’s engaging teaching style.” Near the bottom, in second last place, was “small class size.”

One common complaint about large classes is that students will get less face time with their professor, or even their TAs. The reality might be the same as it is for other classes: students simply don’t take advantage of a professor’s office hours. “For the most part, office hours are very underutilized,” Haffie says. He’s even tried holding court in the cafeteria and sending TAs to residences to hold their hours. Still, the students don’t come.

Rodriquez might have an explanation. “One-on-one with the professor is kind of intimidating,” she says, preferring to ask her questions by email.

Student faculty ratios remain one of the most common metrics when administrators and professors consider the quality of education. University “accountability” measures, often posted on an institution’s website, will usually prominently feature average class size.

A September study published by the Ontario Confederation of Faculty Associations (OCUFA) found that 57 per cent of academic staff in the province say education quality has been declining over the past year. Growing class sizes was seen as the main culprit, as 55 per cent of respondents reported larger class sizes and 38 per cent said retiring or departing faculty had not been renewed. As a result, 38 per cent said that out-of-class support for students had declined, and 39 per cent were using fewer essay-style exams to compensate for larger classes.

OCUFA advocates an investment from the Ontario government to bring student-faculty ratios down from 26 to 1 to the national average of 19 to 1.

James Turk, executive director of the Canadian Association of University Teachers says “anecdotes” from across the country suggest similar trends are occurring elsewhere. While Turk is not too concerned by class size in and of itself, noting that “it doesn’t make a difference” if classes have 100 or 1,000 students, he is worried about what he says is a decline of resources invested in the classroom. Professors are “reporting the number of TAs [per class] are getting worse,” he says.

While Turk is sceptical that technology and quality lecturers can mitigate the challenges of large classes, Meaghan Coker of the Ontario Undergraduate Students’ Alliance says that it would be more efficient for the government to invest in instructor training aimed at encouraging more active learning techniques. Reducing class sizes alone may not make much of a difference. “You could have the same horrible boring teachers, just teaching more classes,” she says.

Similarly, Jeffrey Niehaus, a psychology instructor at the University of Victoria isn’t so sure that more TAs is the answer. His first year psychology class has 300 students, and is coordinated along with two other sections of equal size. In total, there are only three TAs, plus a senior TA who oversees the others. That’s 225 students per TA, but Niehaus insists it hasn’t been an obstacle. “We work them pretty hard and we automate as much as we can,” he says. “If we had 30 students for every TA, I’m not sure we would have put the effort into getting things online.”

Each week Niehaus’ students complete small assignments online that the course website marks automatically. The students are also asked to do several short essay assignments throughout the term, also online, that the TAs are required to grade. Like Haffie at the University of Western Ontario, Niehaus employs clicker technology to pose questions to the class, but also to survey students to quickly illustrate psychology lessons with a live sample.

Krystal Dash, one of Niehaus students, cites his energy, use of pop culture references and humour, as factors that contribute to the success of the class. “You don’t feel that it is a huge class,” she says. Though Dash admits that large classrooms are not always ideal and more intimate settings allow professors to more easily have a back and forth conversation with students. “I do like the smaller classes,” she says.

Teachers like Niehaus represent a new brand of professor in Canadian universities, those dedicated predominately to teaching. While most universities have some sort of position for teaching-only professors, compensating them and putting them on tenure track, similar to traditional research oriented faculty is only starting to take form. Niehaus was recruited from the University of California-Santa Barbara last year, and is on tenure track to become a Teaching Professor, a tenure stream that didn’t even exist at the University of Victoria five years ago.

The growing trend of putting the best teachers—those who are engaging, tech savvy and up to date on the latest pedagogical techniques—in front of large lecture rooms may mean students in those classes, at least in first and second year, are actually at an advantage over their peers in smaller classrooms.

While small classes offer more opportunities for students to interact directly with their professor during class time, unless the instructor is capable of controlling the class, it can often degenerate into a situation where only a handful of students actually get the professor’s attention. “[Small classes] tend to be more easily monopolized by some students,” says Jennifer Marinucci, a third-year English student at the University of Guelph.

What is really needed says Haffie is more research into what classroom techniques actually work. “There’s a whole lot of teaching going on,” he says. “There’s not a lot of investigation into it.”