Talks end between Confucius Institutes and U Manitoba

Academics debate whether to accept Chinese cash

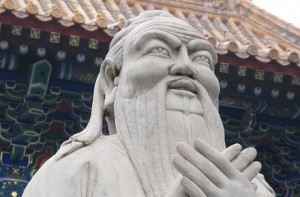

Photo courtesy of IvanWalsh.com on Flickr

Share

When he first heard from a university administrator about a new Confucius Institute (CI) proposed at the University of Manitoba, Asian Studies professor Terry Russell asked for a meeting with the dean in charge. At that meeting, he asked her to carefully consider who was offering to pay for it. The money would come from the Hanban, an arm of the Chinese government that’s chaired by the minister of education. That’s the same government, as Russell put it, that jailed Nobel-prize winner Liu Xiaobo for 11 years, the same government who took the University of Calgary to task after it gave the Dalai Lama an honourary degree, and the same government that employs 50,000 citizens to scour the Internet in search of dissent. Russell says that Canadian universities shouldn’t take money from an education ministry that does such things.

Less than six months later, the university has announced that it will join a short-but-growing list of institutions that have decided against taking Chinese government money to set up CIs on campus. The university’s spokesman, John Danakas, says that “overtures were made” by Confucius Institutes earlier this year, but that “conversations have ended… for logistical reasons.” Pennsylvania State University, the University of British Columbia and the Republic of India, have also decided against CIs on campus.

But in the same month that Manitoba declined funding from China, the University of Regina and Brock University both inaugurated their new Confucius Institutes, bringing the total number at Canadian post-secondary schools to eight. More than 320 exist worldwide. China says that the funding of CIs—$150,000 initially and up to $200,000 per year after that— is meant to promote cultural understanding. But along with the money, schools, including Brock, have signed constitutions that says that “institute activities must … respect cultural customs, and shall not contravene concerning laws and regulations in Canada and China.”

Quite what that means is open to interpretation.

Russell says that means employees will feel dissuaded from mentioning Taiwan, Tibet independence, Falun Gong, or the Tiananmen Square massacre. If that’s true, the result could be an unrealistically positive view of China among the students who pass through the free language and history courses that they offer on Canadian campuses. He goes even further than that. “They’re nothing more than a propaganda and public relations exercise within the legitimizing framework of a university,” he says.

Sheila Young, Director of Brock International, takes the opposite view of their new CI. There isn’t any propaganda, she argues, but instead a fantastic opportunity for academic exchange with the world’s next superpower. “We’re in complete control of the curriculum and always have been, always will be,” says Young. The Chinese government offered to provide textbooks to them during at the Confucius Institutes Conference that she and other administrators attended in Beijing in December, but Brock has not decided which materials it will use. “Nothing has been shipped to us, where they said, ‘here these are prescribed texts,’” says Young.

Young stresses that the CI will allow them to offer many more Mandarin courses than they would be able to otherwise, plus teacher-training certification and possibly Chinese history and political science courses in the future. “There are a lot of cutbacks in the economy we’re in now,” says Young. “So the idea of getting some funding to teach in an area that hasn’t been taught [in] before is appealing.”