What two epic albums say about Kanye West and Jay-Z

They’re Batman and the Joker—no, Felix and Oscar

Share

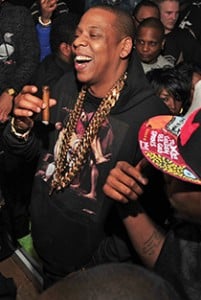

At 12:01 a.m. EST. on July 4, hip-hop fans and music insiders around the world were agog. Magna Carta Holy Grail, the new opus from rap titan Jay-Z, was moments away from becoming an instantaneous bestseller. The emcee had presold a million virtual copies to Samsung for a cool US$5 million; users of Samsung’s Galaxy smartphones who downloaded an Android app would get the album, free of charge, five days before the release date. Commentators puzzled over this brave, branded world. How could Jay-Z guarantee chart success if his album was being given away for free? Was this the future of music releases? By 12:02 a.m., the app had crashed. By 3 a.m., Magna Carta Holy Grail was out there, its beats and lyrics breathlessly parsed by Twitter users. For all the sturm und drang, MCHG made its way into eardrums in the same manner as most other buzzy albums: illegally, on the Internet.

Losing control of your product is an occupational hazard for modern pop stars. The website Has It Leaked exists to keep track of whether unreleased albums have made it on to iTunes playlists. It takes a true businessman to parlay the inevitable into an opportunity to make major cash. And it takes a mogul to turn the entire exercise into an extension of his personal brand. Jay-Z’s approach to his Magna Carta-stravaganza—which included no one-on-one interviews but weeks of behind-the-scenes “trailers” for individual tracks, and lyric sheets that mysteriously made their way online—is a neat summation of how the man who calls himself “Hova” (after “Jehovah”) wants to be seen. In a 2012 profile in the New York Times, author Zadie Smith described his persona as “cool, calm, almost frustratingly self-controlled,” and quoted rapper Memphis Bleek, a long-time acquaintance, who said Jay’s self-contained confidence goes back decades: “This was Jay’s plan from day one: to take over. I guess that’s why he smiles and is so calm, ’cause he did exactly what he planned in the ’90s.”

While Jay-Z’s carefully arranged dominoes fell, his friend and sometime collaborator, Kanye West, was on a full media tour. Three weeks before Magna Carta surfaced, Kanye West unleashed Yeezus, his much-ballyhooed new album. Instead of carefully calibrated video clips and artfully lo-fi liner notes, Yeezus got an old-fashioned, if abridged, promo blitz: West appeared on Saturday Night Live, performing two of the album’s most politicized tracks. He laid bare his artistic psyche in a New York Times interview through a series of audacious quotes. “All I want is positive! All I want is dopeness!” he declared. Later, he pronounced himself the “Steve [Jobs] of Internet, downtown, fashion, culture . . . I got the answers. I understand culture. I am the nucleus.” (Vulture, the culture blog for New York magazine, turned a selection of his choicest bons mots into spiritual posters.) By the time Yeezus rose, it was hard not to know everything Kanye West thought of Kanye West’s latest achievement: it was inspired by a Corbusier lamp, it was super-minimalist, it was “pushing the furthest possibilities.”

The inevitable Yeezus leak, like the Yeezus press, felt unpremeditated and unfiltered, a sudden outpouring from an artist given to sudden outpourings. Given his history of public fits—lamenting (via Twitter) the paucity of cherubs on his Persian rug, accusing George W. Bush of racism after hurricane Katrina, hijacking Taylor Swift’s acceptance speech at the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards—you could read West as a loose cannon who doesn’t care about his public image. But if his persona isn’t as meticulously constructed as Jay-Z’s cucumber-cool facade, that’s equally central to the Kanye West brand. We’re drawn to his antics and outbursts, his ego-fuelled flights of fancy, because they suggest the wild, unpredictable “authenticity” we associate with true savants.

It’s no coincidence that the allies, whose 2011 collaboration, Watch the Throne, broke iTunes sales records and cemented their collective power, released albums within a month of each other without stepping on one another’s toes. Neither appears on the other’s album; the stark percussiveness of Yeezus sits in sharp contrast to the ’90s hooks, Timbaland beats and Grammy-royalty guests on Magna Carta Holy Grail. The two aren’t Batman and Robin—they’re Batman and the Joker, playing off one another in a bizarre, beautiful, dark, twisted fantasy universe. “Juxtaposing those two personality types has been helpful for Jay and Kanye’s respective brands,” says Cord Jefferson, the West Coast editor of Gawker, who’s parsed the strategic moves of both artists. “Their friendship and professional relationship has this kind of ‘Goofus and Gallant’ or Odd Couple mythology around it, which is a common story the public has always loved. Jay is like the big brother who does everything right and Kanye is the little brother who messes up and throws tantrums.”

West, who earned his stripes as Jay-Z’s producer, represents the mania to his mentor’s gravitas, the knee-jerk reaction to Jay’s considered pause. He can’t beat Jay-Z at his own game—on the worshipful Big Brother, from his 2007 album, Graduation, he raps, “I told Jay I did a song with Coldplay / Next thing I know, he got a song with Coldplay.” So, as Jay-Z and Beyoncé, the king and queen of pop, hang out with the Obamas and live airbrushed lives where even their “revelatory” documentaries are hyper-mediated (see: Beyoncé’s self-directed HBO hagiography, Life is But a Dream), West has his own warped funhouse-mirror version: He’s signed on to girlfriend Kim Kardashian’s family business, the inane reality show Keeping Up With the Kardashians. Jay-Z inches ever more toward patrician political correctness—last year, following the birth of his daughter, Blue Ivy, he condemned the cavalier misogyny of his past lyrics and vowed to stop referring to women as bitches. In contrast, West, even on the verge of fatherhood (Kardashian gave birth to their first child, North West, the day after Yeezus leaked), positioned himself as a lusty creep. There was the boast of a sex tape he might release, there are the crass, racially fraught come-ons on his album (too many examples to name, but let’s pick I’m In It, in which West describes putting his fist in a paramour “like a civil rights sign”).

Some have interpreted all of it as straightforward glimpses of the face behind the mask: “Kanye West the man may be a misogynist,” the online magazine Grantland’s Steven Hyden allows, “but as an artist he was honest.” But if West comes across as juvenile and filthy and silly, if his “hidden self” has flashes of toilet humour and the sexual maturity of a 2 Live Crew song, it’s perhaps because he wants to be seen that way. Authenticity is a powerful sell—although, Jefferson points out, “I don’t believe his is a calculated eccentricity in the way Jay-Z calculated his business demeanour. It may be on display more when he’s in the public eye, but only because that’s what people desirous of attention do.”

Meanwhile, Jay-Z’s lyrics make vague gestures toward the legacy of slavery, appropriation of black culture, his own paternal anxiety, and his love for Beyoncé, but more than anything, he’s drawing our attention to his billions. His album is a measured, almost clinical statement from a man more interested in being an elder statesman and CEO of hip-hop than one of the genre’s creative masterminds. “I think Jay-Z is a culture hero to a generation of consumers who have been socialized to conflate materialism with social change,” tweeted Greg Carr, chair of Afro-American studies at Howard University, 12 hours after Magna Carta hit the streets.

West and Jay-Z cater to different psychic needs, and each is the perfect foil to the other. Jay-Z’s is in fact the archetypal hip-hop story: A former drug dealer who grew up poor, without a dad, in New York’s Bed-Stuy neighbourhood, the man born Shawn Carter rose to become the de facto king of contemporary hip-hop. If he has adopted a posture of gravitas, he’s surely hustled enough to earn it. West, for his part, was raised by middle-class parents in Chicago. He had support, education, comfort; the badass attitude adds much-needed cred.

That division of labour is arguably part of the strategy, and it’s worked. As mainstream pop goes, Yeezus is on the fringes. There are no melodies. It’s confrontational and weird. It also had the third-best first-week sales of any album this year—behind Justin Timberlake and, curiously, Daft Punk. The album, with its erratic sounds and forays into awful taste, sounds like the psychic echo we imagine inside Kanye West’s head. Critics noted it was “difficult” to listen to, but gave it raves anyway. As for Magna Carta Holy Grail, it dropped with a disappointing thud. Influential website Pitchfork condemned the album as “a celebration of unlimited financial privilege and power” that separates even Jay-Z’s fans “into haves and have-nots.” On the other hand, Jay-Z still landed a seven-figure first-day sales tally and prompted the Recording Industry Association of America to rewrite its rules to count initial digital sales toward commercial certification. Those million app downloads may have been a bust, but the numbers still counted. And to Jay-Z, making bank is more important than making a masterpiece. “Jay-Z thinks he’s revolutionary because he’s managed to make a lot of money in a structurally racist society,” says Jefferson. “Then signing a deal with Samsung to help sell smartphones is a revolutionary act. That’s the saddest revolution in the world.” Maybe so, but to borrow a line from The Wire, the game done changed.