Women missing from university leadership

Experts discuss how to improve equality at the top

Melissa Sundardas

Share

While the number of women enrolled in higher education and hired as staff in universities is rising worldwide, the pace of this change and shift in attitude toward women leaders of universities is not happening quickly enough.

Five women who want to speed up equality gathered on Thursday at the Worldviews Conference on Media and Higher Education at the University of Toronto for a panel discussion entitled Majority in enrolment, minority in leadership: expanding the coverage on women.

Zukiswa Kekana, a doctoral student from New York University, told the audience that a greater number of women are enrolled in undergraduate and graduate programs and are shifting from predominantly studying the social sciences to a more broad array of disciplines like health sciences.

That’s where the good news ends. Teboho Moja, a clinical professor of higher education at NYU, said that although women are overrepresented in higher education enrollment overall, the American Council on Education’s data show they’re poorly represented at the top. Between 1997 and 2013 in the U.S., women made up only 16 to 22 per cent of university presidents, 13 to 14 per cent of chief business officers and 25 to 43 per cent of chief academic officers (such as deans).

In the U.K., Moja pointed out that the majority of academic staff are women, but they are mainly “the three A’s: adjuncts, assistants and associates”—lower paying and less permanent positions.

“Statistics send a powerful message,” she said. “There is evidence that there is progress, but it’s the pace of the progress that needs to change,” she added. Most people are quick to blame the media, but the university is to blame, she said. “The misconception is that there are no women to fill these roles,” she added. “Just give me five minutes and I will find you qualified women.”

A change in attitude toward women in leadership roles can be achieved if there is a better relationship between the media and universities, so that diverse and positive stories about women are shared with the public, she said. The common profile of female leaders presented in the media is one of a woman who is extremely busy, has long days and couldn’t possibly have time for a family.

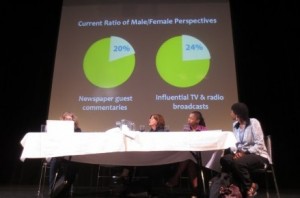

Shari Graydon is founder of Informed Opinions, a Canadian non-profit organization that looks at the media’s representation of women. She pointed to Canadian data that show women are vastly underrepresented on commentary and opinion pages in major daily newspapers and on influential radio and television public affairs talk shows. Only 20 per cent of guest commentaries in newspapers and only 24 per cent of appearances on influential broadcasts were by women.

She said that women are still vastly underrepresented in university “expert” databases too. To combat this, her organization works with women to help them develop skills to make themselves heard in the media. Women are not often willing to come forward, and that’s partly because of “notions that if you were to agree to do media interviews you’d have to get somebody else to pick up your children at the end of the day,” she added.

What’s worse, when contacted by a journalist for a quote, she said women experts are much more inclined to say, “I’m really not the best person,” while males rarely turn down an interview.

She stressed that while women in academia are often reluctant to be put under scrutiny, without their voices many important issues—consent, abuse and equality—could get missed.

Katherine Forestier, director of Hong Kong-based consultancy Education Link, talked about the Manifesto for Change, which was developed by participants in a workshop organized by the British Council called Absent Talent: Women in Higher Education, Leadership and Research. It aims to share experiences of women in higher education and leadership and come up with solutions.

Like the other speakers, she said a common misconception the world must dispel is that women are not progressing in their careers because their lives are interrupted by family.

In sharing their international research, data, and experiences, all four of the panelists said they hoped to send the message that networking is important in order to encourage women to advance as leaders in academia. The speakers urged the audience to be vocal about such issues, saying that it was now up to participants to take this data back to their countries and make change.

Melissa Sundardas is a Toronto-based writer and recent graduate of York University.