Canada’s all or nothing abortion debate

The Conservatives didn’t want to open debate surrounding Bill M-312. MPs weighed in anyway

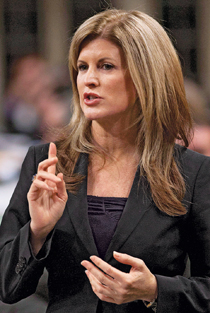

Adrian Wyld/CP

Share

Rona Ambrose is the minister for status of women. She is also the new enemy of the Canadian pro-choice movement, because she voted in favour of M-312 last week, Conservative MP Stephen Woodworth’s controversial motion that would allow for an all-party parliamentary committee to revisit the question of when exactly a human life begins (read: hopefully in the womb, not outside). The motion, which Prime Minister Stephen Harper voted against, was defeated in the House of Commons by a vote of 203 to 91. Critics have called Woodworth’s motion disingenuous; he didn’t officially reopen the abortion debate, they argue, but he tried to start a conversation that might have led us down that path. Lately, however, the question is less about Woodworth than it is about Ambrose: should a champion of women’s rights, especially the federal champion of women’s rights in Canada, be supportive of any legislation that could potentially bring abortion laws back to Canada? (In 1988, the Supreme Court struck them down.)

A lot of people think not. In particular, Ambrose has raised the ire of women’s groups and certain politicians, most notably the official Opposition. NDP MP Niki Ashton practically called for her resignation on the web (“time for a new minister,” she tweeted) and a number of online petitions followed suit—one of which, on the activist website avaaz.org, has more than 15,000 signatures. Janet Currie, a board member of the Canadian Women’s Health Network, told me last week the abortion debate “should no longer be in the public domain” and it’s “contradictory that a minister who’s supposed to be defending women’s rights” would try to reinstate it.

But things are not always as they seem. Ambrose has been fairly quiet in the wake of the backlash, but she did reveal, in less than 140 characters, her actual motivation for voting yes on M-312. “I have repeatedly raised concerns about discrimination of girls by sex-selection abortion,” she tweeted last week. “No law needed, but we need awareness!” In other words, Ambrose isn’t interested in legislating against a woman’s right to choose. Rather, she would like to have a discussion about the motive behind that choice, more specifically, the choice of aborting a fetus because it’s female. M-312 may have died last Wednesday, but it left something behind: the awkward reality that the reproductive rights feminists fight for are the same rights used to discriminate against female fetuses via sex-selective abortion.

Margaret Somerville, the founding director of the McGill Centre for Medicine, Ethics and Law, pointed out this apparent contradiction—and hypocrisy—in the Globe and Mail last week. Pro-choice activists like Joyce Arthur, executive director of the Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada, she wrote, are “willing to selectively sacrifice unborn female babies to keep the ‘purity’ of their ideology, at least in terms of ‘choice.’ ” Somerville is right. Such a position is both hypocritical and extreme. But perhaps it’s the only viable one out there.

The problem is the slippery slope. Once you deviate from an absolute position and start debating which abortion choices are repugnant and which ones aren’t (gender selection vs. mentally handicapped vs. conceived by rape, etc.), you’re no longer debating that the fetus is a person. You’re arguing that some fetuses, let’s say females, are persons, and others, let’s say kids with Down’s syndrome, are not. It’s pretty obvious, especially from Ambrose’s pro-life moment last week, that the public’s indignation is stronger when it comes to sex-selective abortion than a Down’s abortion, or any other kind of health-based selectivity. Which isn’t to say that one day Canada will or should legally restrict some forms of abortion—that some choices should be permitted and others shouldn’t—but that the abortion debate reveals something reflexive about our society: that when it comes to moral dilemmas, we often operate on a utilitarian grading system disguised as compassion—a system of selective mercy that reveals who we value and who we value less.

What this debate has crystallized for me, however uncomfortably, is something simpler: that abortion is an all-or-none paradigm. The only good-faith way of approaching it is to ask whether or not a woman has the right to dominion over her own body. If she doesn’t, all bets are off, and we’re headed back to the days of the pre-1988 therapeutic abortion committees that determined which abortions were kosher, and which were not. If she does, however offensive we may find it, nothing about the sex, physical condition, or for that matter, the shallowness or depth of the mother’s reasons for aborting, have any bearing on the argument. Your personal feelings may be mixed, but her choice must be absolute. The compensations have to be the imperfect ones of a free society: censure, comment, persuasion—but not a law. For me, the most eloquent expression of this idea comes, ironically, from another member of Parliament, one who voted for M-312, Conservative MP Brent Rathgeber. “I am, in my personal life, pro-life,” he wrote in an opinion piece on the Huffington Post. “I struggle with the notion that a fetus, not completely exited from its mother, is not human life. As I am tolerant toward individuals who feel differently, I am prepared to allow them the freedom to choose differently than I would if in their circumstance. In that regard, I am pro-choice. I am not prepared, as a legislator, to impose my opinion on others; although, ultimately I would hope that they will choose life.”