Day 24: Horror on the Trans-Canada

“Five more minutes, five more minutes …’ Memory of tragedy never fades

A site of unimaginable horror

Share

Ottawa, Ontario –

Trans-Canada distance: 2,624 km

Actual distance driven: 6,486 km

NOW: (OTTAWA) The story stays with me even today, 20 years after I first covered it as a reporter for the Ottawa Citizen newspaper.

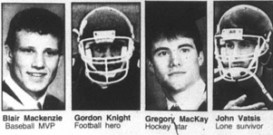

Four young high school football players drove from Ottawa to visit a relative in Montreal, then left at midnight to drive home. Along the way, something happened and the driver slewed off the road into the centre median. The van careened through the grass for half a kilometre before it launched over a small river, smashed into the opposite bank and dropped down into the water.

Three of the young men were killed instantly, The fourth, the 19-year-old driver, broke his leg and both ankles and could not climb up from the wreck, but the van was out of sight below the highway. Eventually, after more than 30 hours in the ravine, he pulled himself up to the road and was found by a passing motorist.

It’s a horrific reminder of how cruel the road can be. I’ve always wondered what happened to that young man afterwards, so today I found his mom and she put me in touch with him by phone.

John Vatsis, who now lives near Toronto, says the memory of that crash never fades: “I remember it clear as day. Greg and Blair were in the back sleeping and Gord was beside me and he was falling asleep too. I said to him not to fall asleep on me, but he did and I was tired too, so I was nodding. I kept saying, ‘five more minutes, five more minutes and I’ll stop.’

“All of a sudden, there was just a blank sheet of red in my head. I was looking at my friends and their eyes were closed and I knew they had passed away, their necks were broken, except Gordie, his eyes were open, but he had passed too. I didn’t feel any pain. Eventually, I got the van door open, but when I stepped into the river, there was two feet of water and my ankle just twisted in it like rubber. It was crushed.”

John says he crawled back into the van and slipped in and out of consciousness all day. He could hear the traffic on the Trans-Canada above and tried throwing rocks up to the road to attract attention, but the high school star quarterback was too weak to throw them far enough. When darkness came, he crawled into the back of the van, past his dead friends, and covered himself with his brother’s hockey bag for warmth. Finally, sometime in the night, “I realized that it really was now or never. I smashed the window on the other side of the van with my helmet, crawled out of the van and used the grass and the branches to pull myself up.”

He was in hospital for several months, and when he returned home, he barely slept, forcing himself to work out so that he could play football again. The next year, his team won the school’s football trophy but his legs hurt too badly to play more seriously; without the sport he loved, he started drinking, and found drugs. He married and had children, but he says he despaired and attempted suicide. He would go back to the accident scene, where somebody had placed three crosses in the grass, and just sit and look at the river’s water.

Eventually, with the help of a psychologist who he now considers one of his closest friends, John says he came to recognize the value of his children and turned his life around. A month ago, he went back to the river for the first time in six years and it was as if he’d finally moved on from the crash. He’s a truck driver who tells everyone who’ll listen to not drive if they’re tired, and he’d like to speak to schools about the fragility and responsibility of life.

“My eldest boy is 12 – he knows about my accident,” says John. “I try to teach him about these things because you know, you think the world of your dad, but these things can happen in an instant. I hope he knows that. Just an instant, and everything’s changed.”

THEN: The old Trans-Canada Highway went through neighbourhoods and downtown areas because it was seen as a commercial boon – merchants lobbied for the road to pass by their businesses.

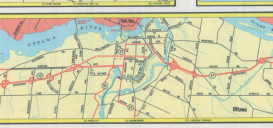

This wasn’t too much of a problem in its first few years in the early 1960s, but it soon became clear that heavy trucks were not welcome on Montreal’s Saint Catherine Street, or in downtown Ottawa. Even though the highway was declared open in 1962, it was obvious that it was not yet finished – the 1962 Ontario road map here shows that the TCH was still running right along Ottawa’s Laurier and Bronson Avenues. It was always planned that a better highway network would offer a bypass around town for commercial traffic, but the pace picked up once the traffic began to build, and an entirely new highway was obviously needed.

In Eastern Ontario, the original TCH followed Hwy. 17, running alongside the Ottawa River at Rockland. But Highway 417 was already under construction to speed traffic past the capital, and the highway was then extended to become a four-lane, high speed highway all the way to the Quebec border.

SOMETHING DIFFERENT … (Ontario/Quebec border) Cross-country travellers know the curse of the Ontario border sign: You see it and think you’re almost there, but in reality, you’ve barely begun.

It’s 2,132 kilometres from here at the southern Quebec border to the border with Manitoba, and that’s the quick way, missing out on Toronto and the entire Southern Ontario region. Truckers know the distance to be at least 24 hours of non-stop movement, while recreational drivers think of it as being a good three days of rocks and trees between Toronto or Ottawa and the start of the prairie.

It’ll be a lot longer for me, taking my time to meet people and see things. Join me here to share the journey.