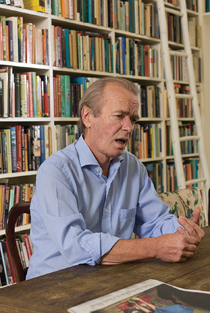

Author Martin Amis on leaving England and finding America

In conversation with Mike Doherty

Photograph by Lee Towndrow

Share

Martin Amis moved from London to New York City last year, and his new novel, Lionel Asbo, has widely been viewed as a parting shot at his native U.K. But Amis himself sees it more as a goodbye hug, even though it’s a satire about a lout who wins a lottery and becomes a ridiculous public figure. Over the phone from a lodge in British Columbia, the author of Money and London Fields spoke with Maclean’s about America, England, new beginnings, and what he’d like to leave behind.

Q: Are you on holiday now?

A: Yeah, sort of. My wife [writer Isabel Fonseca] is doing a travel piece, and I just tagged along. It’s all hiking and kayaking and whale-watching, and I’m an indoorsy type. It’s great, ’cause I don’t have to be taking notes or involving myself in anything. I can just get on with my stuff.

Q: You’re now based in Brooklyn, I take it, for family reasons?

A: Just over two years ago, my mother died, and within a week, the prognosis for Christopher Hitchens was available. That got us thinking about mortality and my wife’s mother and stepfather. We thought, “They’re not going to be around forever.” At this point, it looked as though Christopher might well have lived for five or 10 years more, and those two considerations were enough. It was expressing no disaffection for England.

Q: That said, over the years you have mused about moving to the U.S., because Britain is “not exciting.”

A: The truth is, I’ve never been interested in British politics—or interested only to the extent that it relates to American politics. There’s undoubtedly a kind of gravitational attraction exerted by the centre of the world. Things that happen in Washington matter all over the world, and that has long ceased to be the case for London.

Q: You covered the Iowan Republican primary for Newsweek, and you’ve described Mitt Romney as looking “crazed with power.” What do you make of his running mate, Paul Ryan?

A: It seems to me quite an aggressive choice, making no bones about the fact that this is a plutocratic-leaning party, that money has entered politics in the last couple of years much more obtrusively than ever before. It seems that the Republican party’s just burning itself out and I think will lose the election and will then have to go back to the drawing board. Q: The Tea Party continues to splinter the GOP. A: Only a heavy defeat would get rid of them entirely, but I think the social issues that keep bobbing to the surface, like gay marriage and abortion, are losing their grip on the populace at quite a rate.

Q: What did you make of all the brouhaha in the press about your move to Brooklyn?

A: So far I’ve had a very nice welcome. I had a very weird exit from England. In America, there isn’t the suspicion of writers that there is now in Britain, because everyone understood that writers would play a part in defining a new country. Britain would be so very resentful of any attempt to define it, because its culture is so much more deeply embedded.

Q: Does that also explain some of the spleen that’s been directed at the subtitle of your new book: “State of England”?

A: Yeah. That was all a sinister coincidence, really, because I was halfway through the book when we had this fairly sudden decision to move. And it does look like my verdict in leaving was that novel, but that’s erroneous. It was more my affectionate evocation of Britain.

Q: Some reviewers have critiqued Lionel Asbo as being derogatory toward the working class; they focus on Lionel, who’s a criminal, rather than his hard-working nephew, Des, the book’s other main character.

A: He’s a celebration of the working class. It was much more of a challenge to create Desmond because of the inherent difficulties of making goodness interesting on the page. Something that Dickens, who was my great god when I was writing this novel, in fact failed to do: his goodies are famously insipid and dull. We don’t read Dickens for Little Nell and Esther Summerson; we read him for Quilp and Carker—all the villains and the wags and the eccentrics. That’s where Dickens’s energy goes. To channel energy into a good character is very difficult, and not very many writers have made goodness, happiness, the positive, work on the page.

Q: Your last novel, The Pregnant Widow, has an epigraph by 19th-century Russian socialist Alexander Herzen. Lionel Asbo’s sections start with variations on the chorus of the Baha Men song Who Let the Dogs Out. How did it work its way into the book?

A: It was the initiating idea. Ideas for novels often come from an overheard conversation, or something you see in a newspaper—Lolita began life that way. I was reading about someone who, as an act of revenge, unleashed his pit bulls on the infant of his enemy; that was the first thought I had when the novel was taking shape in my unconscious. I wanted that kind of chant, that incantation, because the lines are very resonant for me.

Q: When Lionel’s pit bulls are treated well, they become loving, and when they aren’t, they’re violent. Is this a metaphor for the English?

A: Well, a universal metaphor. One other surprising thing about the novel snuck up on me as I was writing—it’s to do with intelligence. Desmond idealistically cultivates his own intelligence and worships it and values it, whereas Lionel hates it; Desmond [observes] that Lionel gives being stupid a lot of very intelligent thought. And I realized that all my life I’ve hung out with people a bit like Lionel and Desmond; even the most law-breaking of them is in fact amazingly vivid and articulate and expressive. I feel that down there, in the underclass, there is a great deal of thwarted, trapped intelligence. It becomes self-destructive, and then out of that comes a sort of delight in stupidity, which nearly always includes a delight in violence. There was an old [Tony Blair-era] Labour slogan that just said, “Education, education, education,” and I found myself very strongly agreeing with that, and feeling that that is in fact the core political question. I see the job description of the novelist [as] playing some sort of role in the education business.

Q: You’ve said recently that the novelist has to love his characters as well as his readers. Is this different from your oft-quoted sentiment that “the author is not free of sadistic impulses”?

A: Ah, [laughs]. Well, I think they don’t completely rule each other out, but it’s become clearer and clearer to me that the world is there to be celebrated by writers, and in fact this is what all the good ones do, and that the great fashion for gloom and grimness was in fact a false path that certain writers took, I think in response to the horrors of the first half of the 20th century. Theodor Adorno’s line, “No poetry after Auschwitz,” is in fact contradicted by Paul Celan, who was writing poetry in a Romanian labour camp.

Q: Is it harder to get across the idea of celebration when writing about the Holocaust, as with the novel you’re working on now?

A: Yes, it is slightly more difficult, but interesting. And [I’m writing about] an absolutely hateful character, but Nabokov, who was always a very good guide in these things, was convinced that the way you dealt with extreme villainy in fiction was not to punish it. Your villain is not to be tritely converted, as Dickens tended to do, but the novelist’s job is bitter mockery, and that’s part of how I’m going at it.

Q: I understand that when Christopher Hitchens passed away, you felt that he left you some of his joie de vivre.

A: Yeah. It was surprising, because the death is a disaster, but what surprises you in the ensuing months is that—and wouldn’t it be nice if it were universally true—it’s as if you have the duty to feel that love of life. His was very strong—stronger than mine, I always felt. Wouldn’t it be nice if they do bequeath you that? It warms you, but it also warms your memory of them.

Q: You called the publication of last year’s biography of you by Richard Bradford, for which you were interviewed, a “regrettable episode.” Do you hope that one day a better book will be written about you?

A: Yeah, eventually. But I haven’t thought about it. It was vanity that got me into that first one, but vanity is, I suppose, part of the job. It would be nice, but it doesn’t bother me. What does bother me is being read after I’m gone. I think every writer thinks about that. It’s nicely complicated, and it keeps you honest, because you won’t be around for that.

Q: Much has been written about you and your father, Kingsley, as two generations of uncommonly successful writers. Your son Louis writes non-fiction, and when she was 10, your daughter Fernanda published fan fiction in The Guardian about Harry Potter. Should we be on the lookout for a third generation of Amises on the literary scene?

A: [laughs] As my first wife said, “Yet another nightmare writer is going to appear on the horizon.” I don’t know. I don’t even speculate about it; I think even if I do, that creates a bit of unwelcome pressure for [my children]. I certainly would never encourage them to write. Not that I don’t think it’s a wonderful way to spend your life.