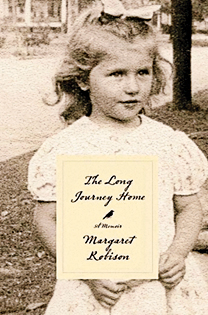

When the author, an American poet, first tried to leave her abusive husband, he yelled, “The cars are mine! The house is mine! The land is mine!” Robison’s close friend (and eventual lover) Suzanne replied: “What’s Margaret’s, John?” Robison, meanwhile, wondered, “Is the story of my life mine?”

When the author, an American poet, first tried to leave her abusive husband, he yelled, “The cars are mine! The house is mine! The land is mine!” Robison’s close friend (and eventual lover) Suzanne replied: “What’s Margaret’s, John?” Robison, meanwhile, wondered, “Is the story of my life mine?”

The first person to tell that story—or a version of it—was Robison’s son Augusten Burroughs, in his 2002 memoir, Running with Scissors. Burroughs depicts his mother as eccentric, narcissistic and often psychotic, writing how she signed custody of him over to her less-than-professional (and possibly also psychotic) psychiatrist, William Turcotte. In her own account, Robison confirms much of her son’s story (not always on purpose), while also providing some context and revealing many more dimensions of her character.

Her tale begins with her own mother, Louisa, whose affection and approval always evaded her, and about whom Robison was deeply ambivalent. At 14, she overheard her mother agonize over the possibility that Robison was gay. At 21, when Robison confessed to being frightened of her future husband, Louisa suggested that she “just tell him.” Instead, Robison married him, convinced that’s what her mother truly wanted.

Fifteen years later, John’s suicidal threats led Robison to Turcotte, and the beginning of a long and destructive relationship. It is hard to say who drove her craziest: mother, husband or shrink. But Robison sees her psychosis as a creative force, ultimately helping her become a published poet (years before her son was a published memoirist). Burroughs derides her talent (Robison claims he despaired having to write in her “shadow”), but his mother has an undeniable gift for lyrical description (particularly of madness). She has more trouble conjuring how her illness affected her children, and claims her abandonment of Burroughs to Turcotte was a technicality so he could attend a certain school. Still, Robison’s ability to recover from misfortunes that might have broken her—including a debilitating stroke in her mid 50s, as well as Burroughs’s book—suggests that, in the end, she can clearly claim her life story as her own.