In his fifth novel, Hollinghurst continues his exploration of gay social history, this time in a sly and erudite saga that spans 95 years of British life, beginning at a house party (always a reliable venue for a novel of manners) in Middlesex in the summer of 1913. George Sawle has brought the budding poet Cecil Valance, his best friend at Cambridge, to Two Acres to meet the family—and engage in sylvan sexual antics on the modest two acres. During his visit, Cecil drinks too much, stays up half the night, dominates the conversation and performs pagan rituals at dawn—very much a cat among the pigeons. George is besotted with him. Before the weekend is over, so is Daphne, George’s 16-year-old sister. Cecil kisses her, and writes a poem in her autograph book titled “Two Acres.” But was it written for Daphne? Or George? Or was it just another poem about houses, the topic of much of Cecil’s verse?

In his fifth novel, Hollinghurst continues his exploration of gay social history, this time in a sly and erudite saga that spans 95 years of British life, beginning at a house party (always a reliable venue for a novel of manners) in Middlesex in the summer of 1913. George Sawle has brought the budding poet Cecil Valance, his best friend at Cambridge, to Two Acres to meet the family—and engage in sylvan sexual antics on the modest two acres. During his visit, Cecil drinks too much, stays up half the night, dominates the conversation and performs pagan rituals at dawn—very much a cat among the pigeons. George is besotted with him. Before the weekend is over, so is Daphne, George’s 16-year-old sister. Cecil kisses her, and writes a poem in her autograph book titled “Two Acres.” But was it written for Daphne? Or George? Or was it just another poem about houses, the topic of much of Cecil’s verse?

Whatever, “Two Acres”—and the poetry Cecil later writes in the trenches—secures his place as one of Britain’s great second-rate poets. (One thinks of Rupert Brooke, also sexually fluid, also primarily remembered as a war poet.) The story next picks up in 1926, then 1967, 1980 and finally 2008. Characters who are central in one section play only glancing parts or are absent in another. That is one of the delights of this elegant and demanding work, wondering when and where and with whom we will find ourselves next. Hollinghurst is interested in time—how it changes social mores, individuals and biography. And turns truth on its head.

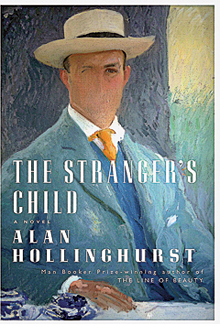

Hollinghurst’s slow pace is often compared to that of Henry James. Which is to say, it can be tiring—you wish he’d get on with his yarn. But this is not fast fiction: it is a detailed universe, one that rewards the reader’s patience. His last novel, The Line of Beauty, won the 2004 Man Booker Prize. The Stranger’s Child got only as far as the long list. Many feel Hollinghurst was robbed.