Year One: The untold story of the pandemic in Canada

In March of 2020, Canadians started dying of COVID-19 and the country shut down. This is a comprehensive report on the country’s mishandling of the crisis of the century.

Share

We gave our entire April 2021 issue over to a single piece, written by Stephen Maher and edited by Sarmishta Subramanian. The 22,000-word story is the most comprehensive accounting yet of what went wrong, and right, in our nation’s handling of the pandemic. Learn more about why we did it.

Chapter One: A danger dawns

‘Everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world; yet somehow we find it hard to believe in ones that crash down on our heads from a blue sky. There have been as many plagues as wars in history; yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise.’

—Albert Camus, The Plague

In the last hours of 2019, Dominic Cardy and Julie Smith checked into the Arenal Observatory Lodge & Spa, a hot spring resort in La Fortuna de San Carlos, Costa Rica, with a view of the spectacular Arenal volcano, which rises out of a rainforest full of waterfalls, howler monkeys and exotic birds. Their room wasn’t ready when they arrived, so they took the hotel clerk’s suggestion and had a drink in the bar. “And it flashed up on the screen that there had been the first suspected transmission,” Smith recalled later.

Smith heads a literacy organization in New Brunswick, but for 10 years she worked for the federal government, mostly in Ontario, doing policy work in areas including counterterrorism. Her boyfriend, Cardy, has been the New Brunswick education minister in the Progressive Conservative government of Blaine Higgs since 2018, but for many years he worked in the developing world for the National Democratic Institute. Self-described policy wonks, they like to unwind by talking about news and ideas, even when they are drinking tropical cocktails in a Costa Rican forest. “So we spent the night in hot tubs, and as normal humans do, spent our New Year’s Eve talking about COVID,” Smith said.

The disease was not then known as COVID-19. (The World Health Organization gave it that name in February.) Few people were thinking about it outside of China. The TV report that Smith and Cardy saw that day in Costa Rica would have been among the first international media reports on the virus, the result of a bulletin issued the day before by ProMED, a volunteer-run information service alerting scientists and doctors of infectious disease outbreaks.

The message, titled “UNDIAGNOSED PNEUMONIA – CHINA (HUBEI): REQUEST FOR INFORMATION,” laid out the earliest news out of Wuhan for ProMED’s 80,000 subscribers:

On the evening of [30 Dec., 2019], an “urgent notice on the treatment of pneumonia of unknown cause” was issued, which was widely distributed on the Internet by the red-headed document of the Medical Administration and Medical Administration of Wuhan Municipal Health Committee.

On the morning of [31 Dec., 2019], China Business News reporter called the official hotline of Wuhan Municipal Health and Health Committee 12320 and learned that the content of the document is true.

The report was based on a Google translation, which explains why a red notice was called a “red-headed document.” It described four patients with fever, in acute respiratory distress that failed to respond to antibiotic treatment. Dr. Li Wenliang, a 33-year-old ophthalmologist at Wuhan Central Hospital, had sent messages to a private WeChat group warning medical school classmates: “There are seven confirmed cases of SARS at Huanan Seafood Market. The latest news is, it has been confirmed that they are coronavirus infections, but the exact virus strain is being subtyped. Protect yourselves from infection and inform your family members to be on the alert.”

When someone posted Li’s message on a bulletin board, Western virus watchers were alerted, and so were Chinese police. They detained Li and seven other medical staff for violating a Chinese law against spreading rumours. They forced Li to issue a statement retracting his warning. He was allowed to return to his hospital, where he contracted the disease, which killed him on Feb. 7. He is now celebrated as a hero in China and around the world.

Early on Dec. 31, the Reuters news agency in Beijing reported that the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission was investigating 27 cases of viral pneumonia. Chinese officials reported the outbreak to the World Health Organization (WHO), and global media organizations started to take notice. The same day, authorities closed the market in the heart of Wuhan (population 11 million) that had been identified as the locus of the outbreak.

On the other side of the world in Costa Rica, Cardy and Smith read everything they could find about the mysterious virus. “I remember raising it with her, [saying] ‘This doesn’t look good,’ ” said Cardy. “All those things you look for that usually make the initial scare around a disease somewhat less scary once there’s more science and data—in this case, every single day, every single new piece of information made COVID seem like it was going to be much more viral.”

Smith was living in Ghana when Ebola broke out in neighbouring countries, when Ghanaians were petrified it was going to spread to their country. She and Cardy were both aware that security experts believed the world was at risk from a new global pandemic—something they had learned at conferences and in their readings—so as they continued their Costa Rica vacation, they talked about the policy implications.

“I think we were unpacking that expectation that we were going to have the 100-year sort of thing, that we were due for a big pandemic,” said Smith. “Were we ready? This could be really bad. It could be the one.”

***

If it was going to be the “one,” the world-shaking pandemic that experts had warned was coming, Canada seemed well-positioned to handle it. After being tested by the SARS outbreak in 2003, Canada had put some effort into building up its public health capacity. And the country was governed by Justin Trudeau’s Liberals, who had campaigned on ending the Conservative “war on science.” The virus didn’t have an ally in this country the way it did in the United States, with a commander-in-chief and state-level politicians who questioned the science and resisted mitigation measures even when tens of thousands were dying.

Canadians could also be reassured by the presence of Dr. Theresa Tam, at the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Tam, the chief public health officer of Canada, seemed the perfect leader for the challenge. Born in Hong Kong and raised in the United Kingdom, she has deep experience with Asia and respiratory diseases. She was chief of respiratory disease at PHAC’s Centre for Infectious Disease Control and Prevention, and working for the agency in 2003, when a Toronto woman contracted SARS on a trip to Hong Kong and brought it back to Canada. It quickly spread through an ill-equipped Ontario health system.

Tam also literally wrote the book on how Canada should manage a pandemic. In 2006, she co-authored “The Canadian Pandemic Influenza Plan for the Health Sector,” a complex, detailed 550-page road map for Canada facing a viral invasion. Tam consulted dozens of doctors, academics, public health officials and other stakeholders, and warned of the risk Canada faced.

With that experience, her 55 peer-reviewed papers and years of high-level experience as an expert with the WHO, Tam would have been among the people in the world best-placed to understand the threat from the mysterious viral pneumonia spreading in Wuhan.

In early 2020, Tam did not yet see evidence that the new coronavirus that was panicking officials in China was going to reach Canada. On Jan. 7, PHAC issued a mild travel warning, merely asking Canadians visiting Wuhan to “avoid high-risk areas such as farms, live animal markets, and areas where animals may be slaughtered.” It’s not that Canada wasn’t paying attention. “Right now we are monitoring the situation very carefully,” said Tam. “There has been no evidence to date that this illness, whatever it’s caused by, is spread easily from person to person; no health-care workers caring for the patients have become ill, a positive sign.”

On Jan. 21, while Trudeau was in Winnipeg for a caucus meeting, he made headlines, not over the coronavirus, but for buying boxes of fancy doughnuts at a local shop rather than at a chain. Tam had reassured Canadians the previous day: “It is important to take this seriously and be vigilant and be prepared, but I don’t think there’s any reason for us to panic or be overly concerned.” The country was much better prepared since SARS, she suggested. “From my perspective a lot has changed from 2003, and we are in a better position to respond to a variety of emerging infections.”

In China, the virus was spreading. By then, there were 278 cases of mysterious pneumonia, the vast majority in Wuhan. There were four cases outside China, in Thailand, Japan and South Korea. The day before, senior Chinese leaders, alarmed by the spread of the illness, had ordered Wuhan locked down. Worryingly, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission had reported that 15 health-care workers in the city had been diagnosed with the illness, a clear sign it was spreading between people. In nearby Taiwan, officials intensified the airport screening they had already implemented weeks earlier.

But in Canada and elsewhere, the virus continued to be a remote concern. On Jan. 23, Tam was among the dozen expert advisers who helped WHO director general Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus decide it was not yet time to declare the coronavirus “a global health emergency.”

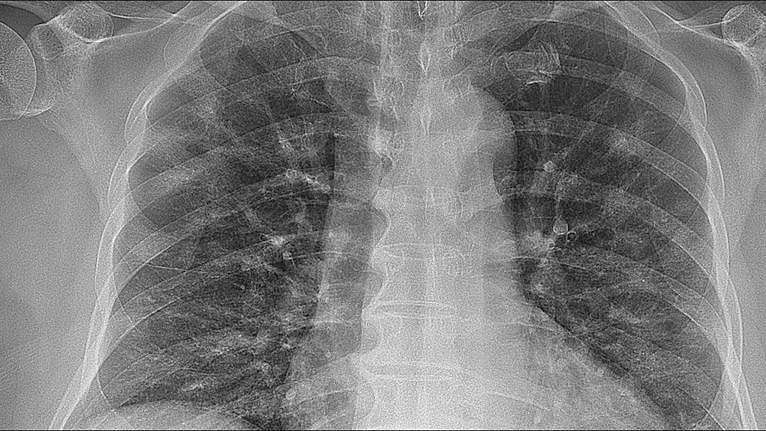

That evening, the novel coronavirus made its debut in Canada. A 56-year-old man who had recently travelled to Wuhan was admitted to Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto. He had a temperature of 38.6° C, a low-grade fever, and was congested. Dr. Jerome Leis, medical director of infection prevention and control, was watching for patients who fit the risk profile. He had an X-ray of the patient’s lungs sent to his home. One look told him what he was dealing with.

“There were diffuse opacities throughout both lungs in different regions of a patient who really only had a few days of symptoms,” he said. “So I thought that was quite striking. Usually, if you hear about someone who’s got a bit of a cold, we don’t expect to see those types of lower lung abnormalities so quickly.”

The hospital sent a blood sample in a taxi to Public Health Ontario’s laboratory, where technicians had been frantically working with information from China to develop a test for the virus. Once Sunnybrook got the result, Dr. Lynfa Stroud, division head of general internal medicine at Sunnybrook, and Leis went to the ward to let staff know they were looking after Canada’s first novel coronavirus patient.

It was a dramatic moment for nurse Kathryn Rego. “They came up to the nursing station and we went into this tiny little room and squished all of ourselves in, and that’s also not a common thing, that every single person on a unit stops,” she said. “The cleaners, our support staff, everyone stopped what they were doing, just squished into this room to hear that this guy was positive.”

The news that they were caring for a coronavirus patient was startling, but not unexpected. Sunnybrook had prepared for the possibility. When Clarice Shen, a nurse in her third month on the job, showed up at work that day she discovered she had been assigned to a “closed” room in the general internal medicine ward, with no patient. Confused, she asked a supervisor about it, and was told the room was reserved in case a patient came in with the novel coronavirus. It was a negative pressure room, one of eight the hospital had set up after SARS, where a patient could be kept in isolation, following protocols for any novel pathogen. A few hours later, she had a patient: the man who had travelled to Wuhan. Shen volunteered to work more shifts so she could care for him, because they could both speak Mandarin. The man had a mild case. He spent a week in hospital, and was discharged.

For Canada, the story was just beginning. There were four confirmed cases by the end of that month; 20 by the end of February; and 8,589 by the end of March. A year after that first patient checked into Sunnybrook, there would be 747,110 confirmed cases in Canada and 19,009 deaths. But already, by that January evening, the microbe known as SARS-CoV-2 had begun its remorseless spread, following its viral logic. Viruses want only to replicate, to find new hosts and fresh lung tissue to infect. To stop them, to curb transmission, societies must follow a narrow path. A few countries succeeded in doing this in that vital first month. Canada did not. It was the first failure of many, setting the country up for a year of challenges we would struggle to meet.

***

In New Brunswick, Dominic Cardy and Julie Smith were worried. Since returning from Costa Rica, they had been tracking news about the coronavirus, texting each other links to stories. On Jan. 23, the same day the patient arrived at Sunnybrook, Smith travelled to Ottawa. Cardy texted her reminders to avoid touching her face. He sent a link to a cellphone video taken in a Wuhan hospital showing patients suffering on gurneys in hallways. “The stuff coming out of China is worrying,” he wrote. “Have you seen the videos? People collapsed in the streets etc.”

“I basically tried not to touch anything at the airport and have used Purell three times this morning already,” Smith replied.

By then, 655 cases had been confirmed around the world, and 95 people were severely ill. There were now cases in Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan and the United States. The virus was spreading in Guangdong province among people who had not travelled to Wuhan. A WHO situation report on Jan. 23 contained a sense of growing urgency. “WHO assesses the risk of this event to be very high in China, high at the regional level and moderate at the global level,” it said; the global risk level was corrected afterward to high.

In the U.S., President Donald Trump was briefed, and on Jan. 24, Congress had its first coronavirus meeting. U.S. classified intelligence briefings, which would presumably have been shared with Canada’s leaders, were warning of a possible global pandemic. The medical community, too, was publicly sharing dire warnings. On Jan. 27, Dr. Gabriel Leung, dean of the University of Hong Kong medical school and a graduate of the University of Western Ontario, made headlines around the world when he revealed modelling showing the virus was much more widespread than China had acknowledged. He followed it up with a Lancet article a few days later telling the world to get ready for COVID-19: “Independent self-sustaining outbreaks in major cities globally could become inevitable because of substantial exportation of presymptomatic cases and in the absence of large-scale public health interventions. Preparedness plans and mitigation interventions should be readied for quick deployment globally.”

On Jan. 30, the WHO finally declared “a public health emergency of international concern,” which didn’t stop China from pressuring other countries to keep their borders open.

Cardy and Smith followed these developments with concern. On Feb. 2, Cardy got the opportunity to do something about it. Louis Léger, the chief of staff to Premier Blaine Higgs, had invited Cardy to his place in Fredericton to watch the San Francisco 49ers and the Kansas City Chiefs in the Super Bowl. Cardy, who doesn’t care for football, jumped at the chance, because he wanted to use it to convince Léger that New Brunswick had to start getting ready for the virus.

Cardy went to Léger’s home, where they watched the game with Léger’s daughter. Eventually, talk turned to politics. “He started off by asking, ‘What’s worrying you?’ ” said Cardy. Léger admits he was expecting a normal discussion about politics. “At that time we were in a minority situation, with all the complication of a minority, the house coming back with a budget,” Léger recalls. Instead, Cardy launched into a discussion of COVID-19. “He was genuinely very preoccupied by it,” Léger recalls. “He was reading, reading, reading, and I think he saw it coming.”

Persuaded by the urgency of Cardy’s observations, Léger asked him to write a report for the premier. Cardy and Smith set to work on it together, in their Fredericton condo. They enlisted the help of Cardy’s sister, Vanessa Cardy, a family doctor who practises in Wakefield, Que., near Ottawa, and in the Cree community of Chisasibi, on James Bay.

Smith was sure the federal government was failing to act quickly enough, imposing travel guidelines after the virus had already moved and constantly struggling to catch up. It was a pattern that would continue. “If you actually read the news, Italy has collapsed because of this. But people can still come from Italy,” she said. “And then we finally deal with Italy, but it’s in the States. It always felt like the response was behind.”

Cardy wanted to make sure that New Brunswick didn’t end up like many other places in the world, where officials learned with horror that their hospital ICUs were suddenly full.

The virus had spread to 32 countries and there were soon worrying indications that officials in Iran and China were hiding the extent of transmission. At a caucus meeting on Feb. 24, Cardy delivered a grim 4,000-word report explaining the risk he saw. He described the impact of “superspreaders,” like the South Korean woman who had infected dozens by attending a church service while symptomatic—a phenomenon that would, months later, become the focus of intense study. He outlined the threat and laid out steps New Brunswick could take using emergency legislation to contain the virus.

“The COVID-19 virus will arrive in New Brunswick,” his paper argued, “and may be already present, given the unreliability of tests, the weakness of Canada’s public health response to date and the nature of our open society. This is not a question of if, but when. COVID-19 will kill some New Brunswickers, infect many others and disrupt the operation of government, the economy and the lives of all citizens. The extent of the damage and disruption cannot yet be predicted, but it will occur. Government will be judged on their handling of this crisis.”

Cardy had convinced the premier. But some public health people were reluctant, he said. “I still remember one of them saying . . . one of the sections in my paper was how to manage a pandemic. And he’s like, well, the first thing politicians need to know is that they shouldn’t manage pandemics. That’s our job.”

Cardy, who was right when a lot of other people were wrong, thinks it was difficult for politicians and health officials—in Fredericton, Ottawa and across the country—to accept the urgency of the situation. “There was a tendency from elements of the bureaucracy that have high levels of trust but had very little experience dealing with anything similar in recent decades, coupled with a political class that’s feeling pretty beleaguered and disconnected and being knocked back and forth by populist movements from left and right. When you combine all those things, it led to a pretty slow and piecemeal and not very well-targeted response, because in Canada, we were weeks and weeks after everyone else was talking about asymptomatic spread.”

Cardy was determined to keep the virus out of New Brunswick. He and Smith connected with Roxann Guerrette, a 30-year-old scientist who was working on her Ph.D. at the Université de Moncton, who was also worried, and they started exchanging ideas about how they could goad a reluctant bureaucracy and an unaware public into action. They had a fight ahead of them, and they still carry the scars, but as of February 2021, New Brunswick has lost only 27 people to COVID. Neighbouring Maine lost 703 and Quebec a horrifying 10,393.

***

In her 550-page pandemic plan, Tam had predicted what was about to happen. “The next pandemic virus will be present in Canada within three months after it emerges in another part of the world, but it could be much sooner because of the volume and speed of global air travel,” she wrote. “A pandemic wave will sweep across Canada in 1-2 months affecting multiple locations simultaneously. This is based on analysis of the spread of past pandemics including the 1918 pandemic.”

Tam knew what to look for, but in January 2020, she was either not seeing it coming, or not making her fears public. She had had experience dealing with SARS, which killed 44 Canadians before it was wrestled under control. In 2005, Tam and five colleagues published a research paper on screening measures—questionnaires and thermal scans—used in Canadian airports during that outbreak with a goal of preventing passengers with SARS from introducing it to Canada. Tam and her colleagues found that although the Canadian government spent $7.6 million on the effort, it did not detect a single case.

Tam knew what worked and what didn’t, knew what resources Canada had, knew the players here and around the world, and knew how a pandemic would behave. She has been a reassuring TV presence throughout the pandemic, delivering succinct public health messages in her mid-Pacific accent, which sounds as if it was picked up at health conferences. She’s not a dynamic speaker, but she is approachable. She told children in a CBC Kids interview that her song of choice for handwashing is “We will, we will, wash you,” to the tune of the Queen classic.

Tam comes across as calm and determined, unflappable, trustworthy, the right person for the job. But she seems to have been wrong about a number of things when it would have been good to be right. In early 2020, her agency repeatedly said the risk of an outbreak in Canada was low. On Jan. 6, a spokesman for PHAC told the Ottawa Citizen that Tam was monitoring the issue, but Canada was well-prepared, in part because of public health systems that would “identify, prevent and control the spread of serious infectious diseases into and within Canada.” Health Minister Patty Hajdu, too, made similar reassuring statements.

Early interventions were modest. On Jan. 22, the government moved to screen passengers from Wuhan at three Canadian airports. When Liberal MP Marcus Powlowski, a Thunder Bay ER doctor, asked Tam in a health committee meeting if it might make sense to ask travellers returning from China to isolate for two weeks, given the virus had moved beyond Wuhan and there were newspaper reports of asymptomatic transmission, Tam said no, bolstering her initial statement that, “for other completely asymptomatic people, currently there’s no evidence that we should be quarantining them.” Hajdu told a teleconference with provincial counterparts that “the risk to Canadians remains low.”

Even after the WHO declared COVID an emergency on Jan. 23, 2020, Tam was warning Canadian leaders against quarantines or travel restrictions, in keeping with WHO guidelines. Tedros had warned countries not to restrict travel more than was necessary: “We call on all countries to implement decisions that are evidence-based.”

Looking back with the benefit of hindsight, it is striking that many public health experts believed COVID-19 could be managed like previous threats—SARS, MERS, swine flu—that flared up, capturing headlines and provoking anxiety before being suppressed. COVID-19, with its easy person-to-person transmission and its long period of asymptomatic spread, would not be stopped as easily.

The same day Hajdu spoke to provincial ministers, Tam warned healthy Canadians against wearing masks. “Sometimes it can actually present risks as you are putting your fingers up and down your face when removing your mask and putting them near your eyes,” she said. She was not alone in this; at that time, neither the WHO nor the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were recommending that the public wear masks, either because the research was unclear on whether it was protective, or because officials feared that hoarding would disrupt the supplies needed in hospitals. In any case, masks would, of course, become a vital piece in slowing transmission.

Meanwhile, the virus moved around the world. University epidemiologists were sounding alarms. And there were countries, particularly in Asia, that were taking the threat seriously, and using the mask policies and border controls that the WHO and Canada were still not recommending. In early January, before there was a single domestic case, Vietnam’s government began monitoring the outbreak’s progress within China and, before long, introduced quarantines at airports, seaports and land borders. On Feb. 3, Japan ordered the cruise ship Diamond Princess quarantined in Yokohama after COVID was confirmed in a passenger who had disembarked in Hong Kong; soon there would be hundreds of infected passengers aboard. Researchers eventually revealed that asymptomatic passengers were carrying the disease, providing an illustration to media consumers around the world of the pernicious nature of the virus. On Feb. 5, Taiwan announced that Chinese nationals were banned from entering the nation; all other travellers had to quarantine for 14 days. By the end of the month, many schools in Japan had closed. After an outbreak in South Korea, the government there declared a red alert on Feb. 23, and other countries started imposing restrictions on Korean travellers.

By late February, the crisis had moved beyond Asia. Outbreaks were appearing in small Italian towns. Venice brought its carnival to an early close and the Italian government suspended sporting events.

All along, in Canada, the government was emphasizing the need for social harmony. There is a long, grim history of ethnic groups being scapegoated during disease outbreaks, and Trump’s anti-China messaging targeted Asians. Incidents of hate surged in the United States in 2020, and the Vancouver Police Department reported a spike in anti-Asian hate crimes in that city.

That well-grounded fear, rather than the threat of a virus that would ultimately take a terrible toll on racialized Canadians, seems to have been top of mind for Canadian leaders early in 2020. At a health committee meeting in Ottawa on Jan. 29, Tina Namiesniowski, then the president of the Public Health Agency of Canada, told MPs the government needed to take care to avoid targeting communities. “This is a vital lesson we learned from our experience with SARS, when a situation arose in which some Chinese communities and individuals were the victims of racism and racial profiling. We must confront that problem,” she said. Tam, in answering MP Powlowski’s question about travellers from China, echoed that message. “The global effort to contain the virus requires the absolute commitment and engagement of the communities that are affected. Otherwise, they’ll be stigmatized,” she said.

Likewise, Trudeau’s first substantial comments about the virus came at a Chinese New Year dinner at a banquet hall in the Scarborough neighbourhood of Toronto on Feb. 1. “There is no place in our country for discrimination driven by fear or misinformation,” he said to applause.

There are indications that behind the scenes the federal government was starting to see the danger. On Feb. 3, as part of preparations for an emergency flight to airlift Canadians out of Wuhan, the Trudeau government made an order-in-council declaring that COVID-19 posed “an imminent and severe risk to public health in Canada.” But although the government had reached that conclusion, it was not behaving as if it was worried. During a teleconference with provincial health ministers and officials—leaders who would before long be struggling with the most serious pandemic to hit Canada in a century—Tam appears to have been focused on keeping everyone calm. “Having been part of the WHO Emergency Committee’s deliberations,” she said, “I can say that the decision to declare a Public Health Emergency of International Concern was based on the need to enhance preparedness and response in vulnerable countries in particular, given the potential for the outbreak to overwhelm their health systems.”

In February, Canada shipped 16 tonnes of masks, goggles, face shields and other personal protective equipment (PPE) to China to help it contain the virus. China, which as the year went on was less and less helpful to Canada, thanked us for the equipment, but before long, people in Canadian long-term care homes were dying in part because staff didn’t have masks. We later learned the federal and Ontario governments had also let PPE emergency stockpiles dwindle, discarding them when they expired rather than replacing them. A CBC investigation discovered that two million N95 masks and 440,000 medical gloves were landfilled in 2019.

As February drew to a close, it was becoming increasingly clear the world was about to face an unprecedented threat. By Feb. 24, the day Cardy gave his grim presentation to New Brunswick Tories, Tam had stopped sounding quite as calm. “These signs are concerning,” she told reporters, “and they mean that the window of opportunity for containment, that is for stopping the global spread of the virus, is closing.”

Canada had failed to take the steps that might have stopped the virus from getting a foothold. COVID-19 was about to put the country through its worst crisis since the Second World War. Some countries saw the warning signs. Why didn’t we?

***

There is a hint of an answer in PHAC’s first public statement about the virus. On Jan. 6, when a spokesperson assured Canadians they were protected by a Canadian centre that describes itself as “an indispensable source of early warning for potential public health threats worldwide including chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear,” he was describing the Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN). But since 2019, GPHIN had not been functioning as it once did. Tam seems to have been flying blind.

GPHIN was established in 1997. In its heyday, it employed analysts and experts based in Ottawa and around the world, who scanned media, stock markets, open-source data and social networks for signs of health threats, acting almost like a high-tech health CSIS, repurposing information to find infected needles in haystacks. They shared those updates with health experts around the world. The system is still functioning, but Grant Robertson reported in the Globe and Mail in July 2020 that it had been downgraded by officials in 2018, who wanted it to focus on more relevant domestic issues, such as the health risks of vaping. Hajdu announced an independent review in February 2021, a tacit acknowledgement that it was broken.

Decision-makers had been warned. In 2018, PHAC epidemiologist Abla Mawudeku emailed international colleagues in despair. “I would like to let you know that, sadly, we have not been successful in convincing management of the critical value and role of GPHIN within and outside of Canada, and the indispensable relationship with the WHO,” she said in an email later obtained by the Globe. International experts, too, lamented the agency’s decline. “GPHIN has been a pioneer in what was, at that time, a totally barren field,” Philippe Barboza, a manager of the WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme, wrote in an email to Canadian epidemiologists. “I cannot understand that this is not recognized.”

GPHIN’s parent organization—the public health agency—had serious problems of its own. An internal audit made public in January 2021 is blunt: PHAC wasn’t ready for a pandemic. “The agency did not have the breadth and depth of human resources required to support an emergency response of this never-seen-before magnitude, complexity and duration,” auditors found, after interviewing “52 key informants.”

“Management noted multiple capacity and skills gaps across the agency,” the audit continued. “Primarily, most noted limited public health expertise, including epidemiologists, psychologists, behavioural scientists and physicians at senior levels.” As we faced the biggest pandemic in a century, the Public Health Agency of Canada didn’t have enough doctors.

When COVID hit Canada, dedicated staffers were working brutal hours, called on to acquire PPE, to help the provinces and territories get ready for contact tracing and set up quarantine sites, to help prepare prisons. But “there was a limited number of quarantine officers within the agency and it was a difficult position to staff quickly because it requires specific education and training,” the audit said. PHAC did what it could to fill the gap, but when Trudeau eventually closed the land borders and called Canadians home in March, there appear not to have been enough people to handle the traffic.

Tam was getting bad advice. “Her office noted that she often received information in the wrong format, with inaccuracies, or in an inappropriate ‘voice’ needed to convey information to a particular audience,” the audit reported. “The modelling information, critical to the public face of the response, and the foundation for strategic planning, was mentioned as being problematic in its initial stages, because of the lack of a coordinated or strategic approach to the work.”

The problems seem to go back to 2014, when then-health minister Rona Ambrose reorganized the agency, which was created after the SARS outbreak, with the chief public health officer in charge. The reorganization, introduced as part of an omnibus bill, demoted the chief public health officer—a doctor—and established a new head of the agency: the president, a civil servant. Ambrose said in the Commons that the move was “aimed at strengthening both its internal management and public health capacity.”

It appears not to have done so. Epidemiologist Michael Garner, who left the agency in 2019 as a senior science adviser, said the reorganization integrated the agency into the general bureaucracy, bringing in people from other departments without the specialized skills a public health agency needs. Garner left in 2019 to follow his ambition to become a priest; he now ministers to souls at the St. Thomas the Apostle Anglican Church in Ottawa, where he has found himself advising the bishopric on how to safely continue pastoral work during a pandemic.

When he left PHAC, he was lead researcher on a team focused on emerging infectious disease risks. He was glad to get out of there. “With the way—under the Harper government—science was sort of frowned upon, with the reorganization, and with the rewriting of this Public Health Agency of Canada Act where the [chief public health officer] was demoted and a president who was a bureaucrat was put in charge, our team was pushed to the side,” he said. His friends who remain at PHAC “have worked tirelessly over these nine months at great costs to their families, to their own health. So I think they’ve done a great job. But I think Canada has done a very poor job.”

Carolyn Bennett, a family doctor before she became a Liberal MP, had established the agency while serving as minister of state for public health under Paul Martin. She opposed Ambrose’s reorganization. “It was [supposed] to be an agency head with the expertise that could go downtown and get the money and be able to set the priorities,” she told the Globe and Mail in 2014. “Anybody I’ve talked to about [the proposed changes] in the public health community has the same two words: bad news.”

But the Trudeau government did not reverse the changes. Garner blames the Harper government for breaking PHAC, and the Trudeau government for failing to fix it.

Bennett had set up the agency so the person in Tam’s job could speak independently. Harper’s government didn’t like being contradicted by scientists, so they changed it. “There was a very clear decision to make a chief public health officer the head of the organization, where that person would have all of the power and that person was empowered to speak to the public,” said Garner. By restructuring PHAC, the government had allowed the scientists to be subsumed by the culture of the amorphous Ottawa bureaucratic blob, which is not always entirely task-oriented.

On Jan. 27, when Tam testified before a Commons committee, telling them it was not necessary to quarantine travellers returning from Wuhan, she was introduced by Tina Namiesniowski, her boss at PHAC, a civil servant with stints over the years at the Privy Council Office, the Treasury Board, National Defence and Canadian Heritage. Namiesniowski, who resigned around the time the audit was written, said Tam was acting “to ensure an authoritative voice to all Canadians during a public health event, which is essential.” The audit said they worked well together, “standing constantly behind one another, supporting each other and sharing the pressure together.”

It seems fair to wonder if they were too close. Was the government listening to Tam, or was it just using her, as Namiesniowski said, as an “authoritative voice” for a government that wanted to project calm?

On March 5, the WHO’s Tedros was blunt: “This epidemic is a threat for every country, rich and poor, and as we have said before, even the high-income countries should expect surprises.” Five days later, in Ottawa, in an incident described by my colleague Paul Wells in an article for this magazine, a reporter coughed into her balled-up fist at a news conference; Hajdu reminded everyone that it’s safest to cough into one’s elbow and to stand two metres apart, which nobody in the Commons lobby was doing. “But I will also remind Canadians that right now the risk is low,” she added, twice.

Unlike Dr. Anthony Fauci, who often gave interviews contradicting the catastrophically dangerous COVID-19 advice of U.S. President Donald Trump, Tam’s comments have been in lockstep with her political masters. That close alignment of messages may be because the Liberals seemed to take Tam’s advice, unlike Trump, whose former adviser expressed a desire to behead Fauci. But it may also be because the Liberals were using her as a spokesdoctor.

“Does Theresa Tam have complete licence to call it exactly as she sees it?” asks Steven Lewis, an adjunct professor of health policy at Simon Fraser University. “If the answer is yes, then arguably Theresa Tam was overly optimistic about how this was going to go. The messaging wasn’t sufficiently clear and there was just too much wiggle room.”

Lewis thinks she does not have licence, that her role is to stay onside with the government she serves. But the public statements Tam was giving weren’t that different from those of Fauci. They were both likely worried about looking like Chicken Little—a bad position for a public health leader. On Feb. 13, health reporter Helen Branswell, who was worried by COVID’s progress, pressed Fauci on why he wasn’t raising the alarm. Fauci asked how it would look if he was wrong. “I’m telling you we’ve got a really, really big risk of getting completely wiped out, and then nothing happens? Your credibility is gone.”

***

I started to worry about the virus on March 11, when I listened to a webinar by Dr. David Fisman, an epidemiologist at the University of Toronto. I was in Punta Gorda, Fla., at the time, fixing up an old sailboat I hoped to sail to the Bahamas. Sitting on my boat, with bad marina WiFi, I managed to download the Fisman webinar and soon found myself sweating, and not from the heat. Fisman had just revealed modelling that projected up to 70 per cent of Canadians could be infected unless we implemented measures to prevent the virus spreading.

Fisman began by explaining to his audience—the Canadian Society of Association Executives—that he was a “little nervous about what I’m going to bump into in the hospital over the coming weeks.” COVID-19 is a recombinant virus, Fisman explained, which means that it evolved while jumping between animal species before moving on to humans. It is “made up of different viral strains that sort of got glommed together into a recombined virus that turns out to be very virulent,” he said. “It makes people quite sick, but [it’s] also quite transmissible, so that each old case makes two new cases or three new cases before they get better.”

That means it can spread exponentially. That was the part that scared me—the terrible silent spread, leading to a sudden wave of illness that could overwhelm hospitals, as was happening in Italy.

“When we have epidemics presenting with deaths, what that means is it’s an old epidemic, because it takes people a while to get sick enough to die,” Fisman explained. “So, we have a bit of a heuristic. If you see two deaths, and we think case fatality is two per cent, those two deaths represent 100 cases, and they represent 100 cases from two weeks ago. So those 100 cases with a reproduction number of two means 200 cases the next week . . . So you’ve got a minimum of 700 cases in your population by the time you see two deaths.”

I emailed Fisman and asked him for an interview for a story. We spoke on the phone on March 12, the same day Ontario Premier Doug Ford told families they should not cancel their March break plans: “Go away, enjoy yourself and have a good time.” I had come to believe Canadians needed to be frightened.

Fisman agreed. “Everyone should be very scared.” He was convinced that governments were acting too slowly, that leaders were failing to grasp the situation. “We have a choice here right now, which is we can be Hong Kong or we can be Italy,” he said. “We get to choose one or the other. We don’t get to choose the status quo. And the difficulty for the politicians is that if you shut things down now and it’s quiet and you achieve what you wanted to achieve, which is nothing happens, then you’re going to be excoriated for overreacting. You achieved what you set out to achieve, which is we didn’t kind of go through what the Italians went through and that’s why we did that. And then people are going to say, bastards! You cancelled the NHL season. And then my restaurant got no customers for a month. You’ve ruined me!”

Fisman was beginning to be a target. The day before I spoke to him, he did an interview with the National Post in which he discussed his model. “The rage that came at me, it’s really something I’ve never experienced before,” he told me at the time. (He has experienced much worse since.) “I think people are scared and there’s a separate grieving thing going on here as well, where there’s denial and anger and all those emotions.”

Before we finished the interview, I decided to ask for Fisman’s advice about my own situation. I had been in Florida for a few months, where boardwalks remained busy and the waterfront bars were still packed with sunseekers drinking pitchers of Bud Light and listening to dad bands. Even after the NBA suddenly cancelled its games, the people I talked to in Florida were unconcerned, dismissing the virus as media nonsense. The Gulf Coast of Florida is Trump country, and the president was telling people not to worry. On March 10, he famously promised it “would go away.” I imagined the virus spreading, silently, and started hiding on my boat, trying to minimize my exposure.

I had started to worry about what would happen if I got the virus. How would I get medical care? How would I get home? I apologized for using an interview subject for medical advice, and asked Fisman what I should do. He pointed out that only three places in the entire state of Florida were doing COVID testing. And there are a lot of seniors in Florida. “If I were in your boots, I’d probably come on back.”

I moved my boat to storage, rented a car and made the long drive north, 2,400 km, from palm trees to snow, past many golden arches and Exxons, up Florida, through Georgia and the Carolinas, around Washington, D.C., then up through Pennsylvania and New York state. I listened to Albert Camus’s 1947 novel The Plague as I drove. I wore disposable gloves when I filled the gas tank. I avoided restaurants and bathrooms. When it got cold, in upstate New York, I parked at the edge of a truck stop and changed my clothes in the darkness of the parking lot.

At first, there were a lot of RVs, trucks hauling boat trailers. The parking lots in the malls and roadside barbecue joints were full. The further north I got, the more seriously people seemed to be taking the virus. In Pennsylvania and New York state, the digital highway signs—the kind that usually warn of congestion ahead—all had warnings about the virus.

I was part of an enormous movement of Canadians home—the flight of the snowbirds. On March 16, Trudeau had announced that Canada was finally taking dramatic action, closing its borders to most foreigners. “If you’re abroad, it’s time for you to come home,” he said.

About a million Canadians returned that week—in planes from airports around the world, and a huge wave from trailer parks and retirement villages in Florida and other U.S. states. It was an unprecedented influx.

Trudeau had called us home, but somehow there was no plan to safely handle us. The airports were a mess. Travellers were jammed together in waiting areas. Masks were still not recommended, and few were wearing them, a shocking contrast for Canadians returning from Asia, where everyone was masked. Scott Grant and his wife flew from Thailand to Vancouver on an Air Canada flight, on their way back to Saskatchewan after a long holiday. When they stopped in Hong Kong, they had their temperatures checked repeatedly with thermal sensors. On the flight, everyone was masked. When they arrived in Vancouver and left the plane, the passengers at the next gate appeared to be coming from a different world. “We pull up beside a flight from London, and not one person from the flight got off with a mask on,” he said.

Not for the last time in the pandemic, there was a gap between the official version and reality. On March 13, Public Safety Minister Bill Blair tweeted: “We have enhanced screening measures in place at all international airports, as well as land/rail/marine ports of entry. We are taking the necessary steps to ensure that Canadians are safe in the face of COVID-19.” But travellers were quick to respond on social media with stories and pictures showing those measures weren’t being implemented. Glen Canning, a Nova Scotian resident in Toronto, shared pictures of a jammed terminal at Toronto’s Pearson International Airport: “I’ve been in the Canada customs line at Pearson for over an hour along with hundreds of people. Six agents on duty, zero screening, no masks, no sanitizer in site. This is as unsafe as it can get.”

Tam was trying to get the message out. “We are asking that all travellers that come back self-isolate,” she said to reporters on March 15. “This is a voluntary self-isolation. It is impossible to keep tabs on every single traveller who comes in. This is a social phenomenon. This is a societal response and everybody must take that responsibility. Public Health is going to do what it can.”

But travellers weren’t consistently being advised to self-isolate everywhere. A passenger freshly landed in Vancouver after a flight from Mexico sent me a cellphone picture of the pamphlet he had received, which did not mention self-isolating.

It remains a mystery why the measures announced by Trudeau and Bill Blair were not being implemented. I sent questions to Public Safety and the PMO last March, which they have yet to answer. Off the record, officials will only say they were overwhelmed.

***

In Moncton, N.B., Roxann Guerrette, Cardy and Smith were solving the problem. Guerrette was then working remotely for Distributed Bio Inc., a San Francisco pharmaceutical start-up researching a universal flu vaccine. Both the company and Guerrette were featured in Pandemic: How to Prevent an Outbreak, a Netflix series released in January, just as COVID was about to go global.

On Jan. 25, Distributed Bio started working to “engineer a panel of anti-SARS antibodies” to treat what later became known as COVID. Guerrette, an Acadian from the northern New Brunswick community of Sainte-Anne-de-Madawaska, became aware from online conversations with colleagues in Europe that the virus could be a dire threat. “I just knew this would be a pandemic before the government started to act upon it,” she said.

Guerrette and Cardy, the N.B. education minister, had gotten to know each other when she was president of the university’s student union. She was impressed by his pro-science approach and in particular by a bill he had tried to get passed requiring mandatory vaccination for all New Brunswick schoolchildren, a measure narrowly defeated in a free vote in the legislature.

As he and Smith worked on their report for the premier in February, Cardy leaned on Guerrette for help understanding some of the scientific concepts. They shared a sense that Canada was failing to get ready. “Scientists have known for a while that this could happen, that there could be a virus that would take over the planet and we’d have to find strategies to mitigate it,” said Guerrette. “We had the Spanish flu. It’s something that can happen again. And Dominic Cardy kinda knew that this could happen again and the best way was to act fast.”

Guerrette sent Cardy COVID-control protocols she had received from a colleague in Israel. She organized a billboard campaign to encourage people to wear masks, which she considered protective, while Tam was still advising people against them. She convinced her boss, scientist Jacob Glanville, to do a video warning New Brunswickers to practise physical distancing, which she and Smith shared on social media. She raised money to get protective equipment for health-care workers.

When Trudeau called people home, a dedicated group of New Brunswickers realized travellers would be bringing COVID with them. Léger, the chief of staff to the premier, said the province knew it had to tell the convoys of returning travellers coming over the border from Maine to isolate. They needed to be instructed to go straight home, without stopping to buy groceries or visit their relatives, but the Canada Border Services Agency wasn’t going to give the instructions. “Their job was to let people in Canada,” said Léger. “Once they are in Canada, that’s another ball game. So they were travelling to Canada, but as soon as they cross over, they’re already home.”

The province put game wardens on the roads in makeshift roadblocks to give health advice to the returning snowbirds. Civil servants weren’t sure. “Are you sure you want to do that?” Léger recalls some asking him. “ ‘Pretty much.’ The premier was absolutely steadfast.”

Cardy and Guerrette tackled the problem at the Moncton airport. He wired her $250. She went to the Canadian Tire in Dieppe, N.B., where she bought tape, 20-litre jugs of water and bottles of bleach to mix to make disinfectant. They printed pamphlets advising people to self-isolate. She went to the airport, said she was acting on Cardy’s authority, and started organizing the arrivals area, getting hand sanitizer for the airport workers and putting tape on the ground to enforce social distancing, directing people over whom she had no authority in both official languages.

The returning travellers needed to be told what to do, she said. “It was a bit of a shock for them and they couldn’t understand that they couldn’t stop at McDonald’s to get a burger on their way home. And we literally needed to put tape on the floor because people wouldn’t listen to the six-foot-distance rule.”

Guerrette got some blowback. She endured social media attacks that still leave her bruised a year later and a country away. She is now working for a biotech company in Boston. “She was personally brave and ready to stand up and put her credibility on the line,” Cardy said. “She didn’t make herself any friends during that period, but she saved many lives.”

Cardy, too, made enemies. Parents complained when he ordered students who had been out of the country on March break to stay home from school for 14 days. Public health officials in New Brunswick opposed the measure, and Dr. Rama Nair, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Ottawa, told the CBC he was being too cautious. Dr. Chris Goodyear, then the president of the New Brunswick Medical Society, said physicians did not believe the measure was rooted in evidence-based public health policy.

Looking back, it seems strange. Tam was wrong, as were many public health experts. On March 11, Steven J. Hoffman, a professor at York University and director of the WHO Collaborating Centre on Global Governance of Antimicrobial Resistance, praised Canada’s measured response on a TVO panel show. “It really highlights the decision that many governments, fortunately not Canada, but many governments out there when they are imposing travel restrictions,” he said. “We see many countries around the world are overreacting to this threat. The overreaction can actually cause more harm than the virus itself. For example, there are 180 million children in China who are not at school. . . ”

Because of the stringent measures China took, that country has been largely free of the virus since March.

In January, Chinese officials were urging citizens to wear masks, part of the successful national measures that suppressed the virus. Tam didn’t advise Canadians to mask up until April, a few days after the CDC changed its policy. Until then, the research was unclear. Both Tam and the CDC were wrong. And because they didn’t advise wearing masks, warned against the risks, in fact, people got infected and died. But they didn’t know they were wrong. Perhaps they couldn’t have known.

It is difficult to remember now all the things we didn’t know then. On March 15, I was thinking about writing an article calling for the cancellation of St. Patrick’s Day, or at least the part most people like about it: drinking beer in bars and listening to Irish music. I emailed Fisman to ask his opinion. I noted the stories from Italy about young people partying and spreading the disease. “Also,” I added, “South Korean data show high rates of asymptomatic young people.”

“God bless the South Koreans,” he replied. But his answer to my question was careful. “They’re delineating the true epi of this disease with the massive testing. Re St. Paddy’s day . . . I have enough trouble in my life without saying ‘close the bars on St. Paddy’s’ in Maclean’s. But one can easily see how bars would be good for spread.”

He, too, was grappling with a strange new world. It should have been obvious that we needed to close bars, but we were both struggling to come to that conclusion. So were our leaders.

On March 13, Dr. Mike Ryan, an Irish doctor who has spent his career doing emergency medicine in the most difficult places in the world, discussed the necessary mindset during a WHO news conference. “The lessons I’ve learned after so many Ebola outbreaks in my career are: Be fast. Have no regrets. You must be the first mover. The virus will always get you if you don’t move quickly, and you need to be prepared. One of the great things in emergency response—and anyone who’s involved in emergency response will know this—if you need to be right before you move, you will never win.

“Speed trumps perfection, and the problem in society we have at the moment is everyone is afraid of making a mistake, everyone is afraid of the consequence of error. But the greatest error is not to move, the greatest error is to be paralyzed by the fear of failure.”

***

Looking back at the pictures Glen Canning took at Pearson airport, it is strange to see so many people without masks crammed together. There is no way of knowing how many people got infected in the crowded lines at Pearson, but likely a lot. And some of them likely died. A Statistics Canada report from April 2020 found a quarter of COVID cases were directly linked to travel.

A lot of highly educated, dedicated and motivated people failed to sound the alarm, and to heed it when others did.

It made me think of the disaster in Aberfan, a Welsh coal-mining town, where mine waste had been piled on top of streams on the hillside above the town. After a night of heavy rain, the pile of debris slid down the hill, where it crushed a school, killing 109 children and five teachers. The tragedy was dramatized in an episode of The Crown, I later learned. But the part of the narrative that is less well-known is that the local council had complained for decades about the slag heaps, which repeatedly flooded parts of the village with dirty water. In 1963, an engineer warned the National Coal Board: “The slurry is so fluid and the gradient so steep that it could not possibly stay in position in the wintertime or during periods of heavy rain.”

But officials at the coal board, who were ultimately found responsible at a public inquiry, ignored the warnings, and so on Oct. 21, 1966, miners who started their day digging coal finished it digging the remains of their children out of what had once been a school.

The sociologist Barry Turner, in a 1976 study of man-made disasters, including Aberfan, found that organizations often have a “tendency to minimize emergent dangers.” Part of the problem is that officials reflexively discount the views of non-experts, like the villagers who warned the coal waste was ready to slide.

The people who see the danger are, like the mythical Cassandra who warned the Trojans there were Greek soldiers in the wooden horse, ignored because they are not part of the group in charge. Experts often respond with a “high-handed or dismissive response,” Turner wrote. Warnings from outsiders are “fobbed off with ambiguous or misleading statements, or subjected to public relations exercises, because it was automatically assumed that the organizations knew better than outsiders about the hazards of the situations with which they were dealing.”

I emailed that quote to Cardy when I came across it.

“I’m framing that,” he replied.

***

Chapter Two: Canada’s strongest bubble

‘What experience and history teach is this—that people and governments never have learned anything from history’—Hegel, Philosophy of History

On March 29, 1919, in the middle of a pandemic that had started during a world war, the Montreal Canadiens faced the Seattle Metropolitans in the Stanley Cup final. It didn’t look good for the Canadiens at the beginning of the third period in the fifth game. Les Glorieux had to win to have a shot at the cup, but they were trailing 3-0, and their best defenceman, scrappy Joe Hall, a man who once said he played so rough he was “giving a dog a bad name,” was too ill to finish the first period. They somehow rallied, led by Édouard “Newsy” Lalonde, who scored two goals to tie the game, before Jack McDonald put them up 4-3 in overtime. It was a thrilling conclusion to what the Vancouver Sun called “one of the best and fastest exhibitions of hockey ever seen here.”

The stage was set for Game Six, but it was not to be. Five Canadiens were in the hospital with the flu. Hall died a week later. The Habs, without enough men, forfeited, but the Seattle side wouldn’t take the victory, and eventually this was engraved on the cup: 1919, Montreal Canadiens, Seattle Metropolitans, Series Not Completed.

Hall was one of about 50,000 Canadians to perish from the so-called Spanish flu, at a time when there were only 8.8 million Canadians. The flu’s impact, like COVID’s, was greatest on the vulnerable, people who couldn’t avoid infection, or count on proper care once infected. It cut a horrible swath through Indigenous communities, who were vulnerable thanks in part to widespread tuberculosis and federal policies that left them malnourished and ill cared for. And its second wave was worse. In 1918, the Canadian government repeatedly seeded the flu by dispersing infected soldiers around the country without considering the consequences. Vincent Massey, who would later become governor general, wrote a scathing report for prime minister Robert Borden, laying out the federal failure: the government, Massey wrote, “could have given specific directions and ensured that a uniform, coordinated plan was followed.”

A hundred years later, as Canada inched toward the second wave of another pandemic, you could say much the same. Ottawa moved quickly last spring to provide income supports, hatching the CERB program within weeks of the country going into lockdown and providing up to $2,000 a month for those deprived of work. Other programs followed for businesses and individuals. They were all criticized for various reasons, but the money kept the economy moving, preventing terrible deprivations.

What the federal government didn’t do is impose a coordinated response on the provinces, as it might have done if it had invoked the Emergencies Act. In the ensuing months, Tam and Trudeau repeatedly called for provinces to take stronger action. The premiers of Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta mostly ignored those warnings, as well as the lessons of history, and the failure to suppress the outbreaks belongs to them.

In late August, as Canadians visited gyms, bars, restaurants and shops, and schools geared up to reopen, the warnings from health experts grew more urgent. So did their calls for investing in rapid testing and contact tracing. By Jan. 15, without adequate measures in place, the second wave had crested. There were an average of 9,600 new cases a day across the country, about 1,000 of them in Toronto. It has been an ordeal, said nurse Kathryn Rego, who helped care for Canada’s first COVID patient in that city last March. “There was never a thought in my mind that we’d be in lockdowns a year later,” she said, “still fighting this thing and seeing the strain on the hospitals and the strain on the staff and just the burnout.”

On the other side of the world, Melbourne, Australia, a city of five million, was heading into its tenth day with no new cases. Steven Lewis, the health policy professor at Simon Fraser University, has spent the pandemic in Melbourne and thinks Australia did better because its leaders were bolder. Lewis, a long-time senior health policy professional from Saskatchewan, found himself in Australia when his partner got a job there. He has been functioning as “head of domestic affairs” for his family, spending his spare time keeping a close eye on pandemic management in both countries. Australian leaders, he found, did not count on everyone taking responsibility for their actions, the approach taken by Canadian authorities early on.

“The first obligation is to have a clear policy, and the messaging [in Canada] has been, for the most part, extremely ambiguous and always leaves a little wiggle room,” said Lewis. “So you get the chief medical officer saying, ‘We really would discourage people from having mass gatherings’ or ‘You really should restrict unnecessary travel.’ Well, what do you mean by that? Are we allowed to travel or not? And who defines unnecessary?”

Even some helping to make policy interpreted the advice loosely. Last November, Dominique Baker, surely the first acting manager at the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Office of Border Health Services to make headlines, took an all-expenses-paid trip from Air Canada to Montego Bay, Jamaica, to stay at an elite resort. She gushed about the luxurious experience on her style and beauty website, and posted about it on Instagram. After the trip came to light, she was publicly criticized by Iain Stewart, who had replaced Tina Namiesniowski as the boss at PHAC. Baker expressed regret and, before long, announced she was leaving the government to pursue her dream of being a full-time social media influencer.

Baker comes across as a sympathetic person on her style website, and her delight at riding a horse on the beach in beautiful Montego Bay is infectious. But she was travelling in the thick of the second wave, for non-essential purposes, while she had a crucial role in the white-knuckle business of managing travel during a pandemic. She was not the most senior Canadian official to abandon her post to sneak away to a sun spot: Rod Phillips, the Ontario finance minister, decided to spend Christmas on posh St. Barts. Before he left, he recorded a series of holiday greetings for scheduled posting online that suggested he was still in chilly Ajax, Ont. More ill-advised jaunts came to light in the first grim days of 2021: Alberta MLAs in Hawaii and Mexico, the Niagara Health CEO Tom Stewart in the Dominican Republic. A number of those people lost their jobs. Some Canadian leaders in charge of protecting the health of the country obviously had other things on their minds.

From the beginning, Australia responded more decisively, shutting down travel from affected areas and enforcing measures meant to control the spread of the virus, with fines and spot checks when necessary. The state government in Victoria implemented a hotel quarantine order for out-of-country arrivals in March 2020, 11 months before Canada took a similar step.

The aggressive action worked in the first wave: Australia had 4,559 cases at the end of March while Canada had 8,589—23 per cent less per capita. That difference only grew. Tough action all but eliminated the virus from Australia within a month, while cases in Canada kept climbing. Australia had the pandemic under control until June (the start of its winter), when sloppy private security guards at a quarantine hotel got infected, leading to hundreds of cases. The virus spread through asymptomatic people attending family gatherings. The second wave was getting out of hand, relatively speaking, until the state government brought in a tough 111-day lockdown in July, with most people confined to their homes—quite a feat in Melbourne, a city of five million. By August, residents had to observe a curfew and stay within five kilometres of their homes, which they were only allowed to leave for essential purposes or for an hour or two of outdoor exercise. Gyms and schools were closed. Restaurants were only allowed contactless delivery and takeout.

“You can’t say, well, because 80 per cent of the population believes the way we do, we’re going to be successful at pandemic control,” said Lewis. Everybody has to be ordered to comply, or the measures won’t work. Australian politicians were prepared to take dramatic steps. Prime Minister Scott Morrison mused about making vaccination mandatory (he later backtracked). Police in the state of Victoria issued more than 20,000 fines for COVID violations, which helped shut down transmission, although human rights groups complained the penalties were applied inconsistently, targeting more minorities. The measures were harsh and enforcement wasn’t perfect, but they worked.

That took political leadership. “You have an enormous political dimension to what is essentially a scientific and technical problem to solve,” said Lewis. The Australians found the political will. Canadian leaders didn’t. We have lost more than 22,000 people to COVID. Australia has lost 909.

Our disorganization and lack of political will means we got sicker and are poorer. “We’re paying a bigger economic price because we didn’t do it,” said Lewis. “It’s not that Australia chose to pay a higher economic and ancillary-health-concerns price in order to do this. They figured if we do it hard and we sustain it and we stick to our goals . . . until it is very clear we can reopen in the long run, we will be better off, not just health-wise, which is incontrovertible, but also economically.”

Crucially, Australia broke with the advice of the WHO early on, imposing travel restrictions while Canada was still following advice from a body that critics think was unduly influenced by China. Australian leaders were not afraid to act quickly and decisively. Canada was always behind the play. “You don’t even know what the puck is at the beginning, let alone where it’s going,” said Lewis. “So to anticipate is critically important and we’ve chased the puck. Canada’s still chasing. They still wait before they move to another level of lockdown.”

***

In July, I moved home to Nova Scotia after 15 years in Ottawa’s ByWard Market, a lively, pedestrian-friendly neighbourhood full of shops and restaurants that was suddenly empty and charmless in March. I was alone in my apartment, working on stories about the shooting rampage in Nova Scotia, struggling psychologically with the tragedy, frustrated at the distance, so I decided to move back.

The Atlantic provinces had restricted interprovincial travel starting in March, requiring most travellers entering the region to spend 14 days self-isolating, and discouraging internal travel during outbreaks. (“Stay the blazes home,” in the words of Stephen McNeil, then Nova Scotia’s premier.) But after a two-week quarantine in a seaside cottage, I was delighted to roam freely in a jurisdiction where everyone wore masks without complaint in the supermarket although there was virtually no infection—two active cases in the middle of July. It felt like a place apart, a land without COVID. Restaurants and bars were full. Real estate agents were overwhelmed with business from Upper Canadians seeking a seaside escape.

The dark side, if you could call it that, was a certain nosiness—part of the social cohesion that kept the region safe. One day, I stopped by the side of the road on St. Margarets Bay to look at an old fish shed—a shingled building on the rocks at the water’s edge. I walked across a lawn and asked the shed’s owner if she would mind if I had a look, and mentioned I had recently moved home from Ontario. She was friendly, and told me that was no problem. “But have you registered?” she asked. I had wandered into a campground, which she owned. Everyone leaving or entering the campground was required, by provincial order, to register. I could look at her shed after I registered, she said.

I agreed and followed her to the office, where I wrote down my name and number. She then asked for proof I had self-isolated, adding that many people were dishonest about the quarantine. She wanted to know I wasn’t fibbing. I declined to show her my travel documents, which I was not required to do, and left, both of us exchanging polite farewells through gritted teeth.

I didn’t like being quizzed by a self-appointed health inspector, but I am sure this kind of vigilance is part of why Atlantic Canada was able to avoid the worst of the pandemic. In Prince Edward Island, some cars with out-of-province plates were vandalized by local quarantine enthusiasts. Cortland Cronk, a New Brunswick software consultant and marijuana nutrients supplier, moved out of the province after he travelled for work, was blamed for an outbreak back home, and criticized online. Atlantic observers were skeptical of his narrative but he received solicitous treatment from the New York Times, which described pandemic shaming as “a worsening civic problem.”

Premier Stephen McNeil, who left office in February after presiding effectively over the pandemic, told me Atlantic nosiness may have been part of the success. “They would let us know if you weren’t isolating,” he said in an interview during his last week in the job. “But on the flip side, we had to tell people just because someone’s here with an [out-of-province] licence plate doesn’t mean they haven’t isolated. It doesn’t mean they don’t have a right to be here.”

“We tried to frame that in a positive way, communities caring for each other, supporting people,” said Robert Strang, Nova Scotia’s chief medical officer of health. “We’re not stressing the compliance if you will, but a bit of that ‘I’d better be careful because somebody may be watching me’ is probably helpful as well.”

McNeil said he and Strang acted decisively in part because they knew the limits of Nova Scotia’s health system. “I was terrified of what was going to happen to our health-care system and to Nova Scotians when it came in,” he said. “That’s why at the front end we were so aggressive.”

The provinces west of Rivière-du-Loup, Que., even in the tightest lockdown in the spring, mostly declined to institute travel restrictions, arguing that the Constitution allows for free movement within the federation. A November study in Nature Human Behavior that analyzed responses around the world found travel restrictions were among the most effective measures globally in curbing the pandemic in March and April 2020, but Canadian politicians mostly declined to impose them. They faced pushback from voters who bridled at the prospect of being kept away from their cottages, which, after all, they own. The virus, which doesn’t care about our Constitution or the requirements of second-home maintenance, took advantage. The district that encompasses Simcoe-Muskoka, the beautiful cottage country north of Toronto (population 550,000), suffered 189 deaths, compared with Nova Scotia (population 970,000), which lost just 65 people, almost all of them at one large long-term care home.

While Ford was telling Ontarians to go away and enjoy themselves on March break, McNeil was warning people they would have to isolate on their return. Nova Scotia and its Atlantic neighbours did a hard shutdown in the spring of 2020. “My background before I came into this office, I was self-employed,” said McNeil. “I knew I was taking four months’ income from people. I was closing them down.” He didn’t want to do it, but is sure it was the right call. “That’s not an easy decision to make, but it was absolutely the right decision. We couldn’t, in the front end, say, ‘We’re going to leave you half open.’ We had to close it to understand it.”

***

In November, it looked briefly as if Nova Scotia was in for a second wave. Cases started rising, as they were across Canada. McNeil and Strang had evidence the virus was spreading through asymptomatic customers in Halifax bars and restaurants, so they prepared to tighten restrictions.

Restaurant owners had a better idea. Gordon Stewart, executive director of the Restaurant Association of Nova Scotia, asked the province to shut them all down.

On Nov. 24, with Nova Scotia reporting 37 new cases of COVID, the province agreed to the industry’s request. Instead of tightening the rules, they ordered indoor dining shut. “We wanted to stay open,” Stewart told me. “The difficulty was, if you shut down and reopen, shut down and reopen, that can be very expensive. It’s expensive being closed, but it’s not as bad as being closed, reopened, closed, which has happened to many parts of Canada, and other parts of the United States and Europe.”

The restaurants and bars lost their busiest season—they remained shut through the holidays—but when they reopened in January, they reopened for good. “We knew if we locked down and made it tight, then that number would go back down,” said Stewart. “And that’s exactly what happened to us in Nova Scotia.”

Former health minister Jane Philpott thinks it is better for businesses if governments lock down hard enough to eliminate the virus. “I think many people would say, yeah, we would have rather been entirely shut down for a month or two,” she said in a recent conversation. “And not have the torture we’ve had over the winter of this long drip, drip, drip of economic challenges.”

Arguments about the social and economic costs of lockdowns really only apply to lockdowns that fail. Lockdowns that work are ultimately good for the economy. As it turns out, in Nova Scotia, according to Stewart, restaurant receipts in January 2021 were at about the same level as January 2020, before the pandemic hit. The province’s unemployment rate is lower than Alberta’s for the first time in memory.

***

There was a moment in the early fall, before the second wave, when provincial governments in most of Canada could have responded more decisively and shut down the virus. Canadians were flocking to malls and gyms and restaurants even as cases were starting to rise. University epidemiologists urged leaders to act. Instead, governments took half measures.

The second wave, like the first, arguably started in Quebec. In September, after a karaoke party at Bar Kirouac in Quebec City led to at least 72 cases, the province responded not by shutting bars but by banning karaoke, which led to angry complaints from bar owners. Quebec Premier François Legault waited until midway through December, when the health-care system was under strain, to take the harsh steps needed to slow the spread.

The Prairie provinces had avoided high case counts in the pandemic’s first wave. Their conservative premiers were among the first to ease restrictions in the spring and summer, and they were reluctant to close again later. Manitoba, which often had no new daily cases in May and June, saw rapid spread start in August, settle briefly, then take off in September. It has had Canada’s highest COVID fatality and hospital rates outside of Quebec in spring. Premier Brian Pallister made an emotional presentation to Manitobans in December, urging them to follow the rules. “So I’m the guy that has to tell you to stay apart at Christmas and in the holiday season you celebrate . . . where you share memories and build memories,” he said, his voice breaking. “I’m that guy. I’m the guy who’s stealing Christmas to keep you safe because you need to do this now.”

In Saskatchewan, Premier Scott Moe cried foul when Trudeau called for provinces to tighten up on Nov. 10. “We can keep our economy open and people working by following sound practices that reduce the spread of COVID-19,” he said. There were 127 new cases that day. A month later, averaging 260 new cases a day, Moe brought in tighter rules. Saskatchewan would have been better off if he had heeded Trudeau’s warning.

British Columbia did better than all but the Atlantic provinces in the second wave. It had a better strategy to protect long-term care homes and a stronger public health system than other provinces. But cases grew there, too, in the fall as Premier John Horgan called an election and the government moved into “caretaker mode,” during which no major decisions are made. Voters gave Horgan’s NDP a majority and a second term on Oct. 24, but some criticized the election’s timing. “The question is whether B.C. deserved more than a caretaker mode from their government during a state of emergency,” said B.C. Green Leader Sonia Furstenau. In January, Horgan rejected calls to order self-isolation for travellers from out of province, which worked so well in Atlantic Canada. He also wouldn’t take action to stop visitors from travelling to Vancouver Island, although the island’s chief medical health officer asked for the measure. Cases have now spiked there.