George-Étienne Cartier: A Canadian nation-builder

George-Étienne Cartier: A Canadian nation-builder

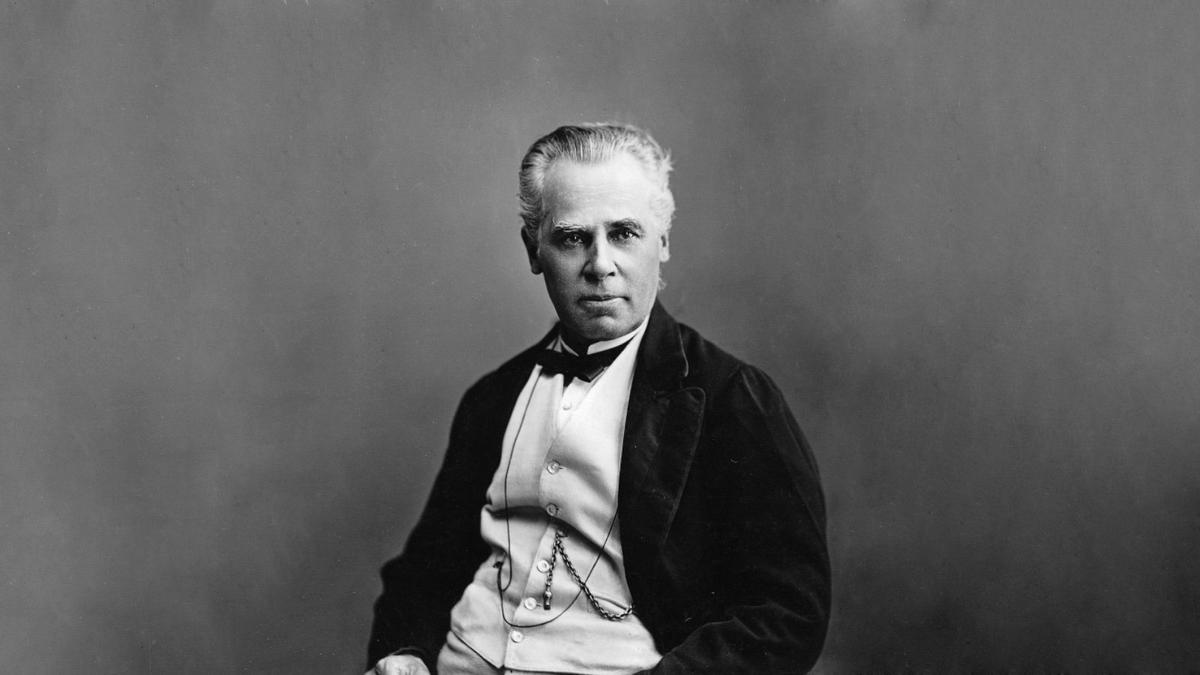

Sir George-Étienne Cartier. (McCord Museum)

GEORGE-ÉTIENNE CARTIER:

NATION-BUILDER

An idealist from Quebec becomes a statesman and a founding father—and comes to embody a certain vision of Canada. Jean Charest and Antoine Dionne-Charest consider George-Étienne Cartier’s life and legacy.

Many a man leaves his mark on history. Few can take pride in having helped build a nation. George-Étienne Cartier was one such man.

Cartier was born in 1814 into a family of shopkeepers, in the village of Saint-Antoine, on the shore of the Richelieu River, northeast of Montreal. He was likely named George-Étienne—with the English spelling, instead of Georges-Étienne—in honour of King George III. His parents, of course, could never have known that, decades later, his political adversaries would see that missing s as proof of his “betrayal” of French Canadians.

Cartier left the family home when he was just ten to attend the Collège de Montréal boarding school, known for its rigorous curriculum. After completing his secondary education, he studied law under Édouard-Étienne Rodier, who would become his mentor. Rodier, a nationalist and an anticlerical who was sympathetic to the ideas of the Patriotes, considerably influenced the young Cartier’s political thinking, and probably his decision to join the Rebellion of 1837. The Patriotes’ principal demand was the institution of responsible government; that is, full sovereignty for the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada. At the time, power rested in the hands of the governor, appointed by the Crown in London: he controlled the purse strings, and wielded the power to revoke any bill passed by the Assembly.

Cartier took part in the Battle of Saint-Denis, the Patriotes’ only military victory. When the rebellion was eventually crushed, he went into hiding in the countryside, and then into exile across the border in the United States. He was granted amnesty after petitioning Lord Durham’s secretary, and returned to Montreal in the fall of 1838. At that moment, the young man did an about-face: he said he had joined the rebellion to combat the local Tory minority, and not the British Crown, to which he now swore his loyalty. From then on, Cartier advocated compromise with the governing authorities, a point of view opposed to that which Louis-Joseph Papineau, the leader of the Patriote movement, continued to defend. The key point here, though, is the transition from the idealistic, militant young lawyer to the man who would become Sir George-Étienne Cartier: a pragmatic lawyer, baronet, businessman, and, eventually, statesman.

View from Notre-Dame Church, looking north-west, Montreal, QC, 1872. (McCord Museum)

Cartier was short in stature and elegant in bearing. His clothing, hair, and manners projected the air of a gentleman, which is perhaps explained by the fact that he was unapologetically anglophile. Like many other people of the time, he was fascinated by the English lifestyle and, in particular, by the city of London, which he visited often. He openly described himself as a “French-speaking Englishman.”

Behind the gentlemanly image, though, was a man who felt equally at home in the countryside of the St. Lawrence River Valley as at fashionable society evenings in Montreal. The Cartier men, merchants from father to son, were known to enjoy entertainment and the company of women. George-Étienne would not hesitate to argue with prominent public figures, even engaging in at least one duel. He never completely abandoned the irreverence of his youth. He was sociable, enjoyed singing and dancing, and, like many men of his day, was known to raise a glass or two. Luckily for him, his love of drink never approached the legendary intensity of that of his later colleague and political ally Sir John A. Macdonald.

His marriage to Hortense Fabre, the daughter of a well-to-do family of the time, was not a particularly happy one. The Cartiers would spend a good part of their conjugal life, if not the majority of it, separated from one another. Hortense lived with their two daughters in their Montreal home, while George-Étienne went wherever politics took him. Their failed relationship was due, at least in part, to Cartier’s chronic womanizing. After her husband’s death in London, Lady Cartier never again set foot in Canada.

Cartier’s political philosophy is best described as healthy pragmatism: his approach to politics always considered the practical consequences, be they political, social, or economic. That philosophy aimed at achievement of concrete results with an impact on the lives of all citizens. But there was more to “Cartierism” than that. Though he was not an intellectual, and even professed to a certain form of anti-intellectualism, Cartier had his convictions. They were inextricably linked to the context of the time in which he lived, that of a French-Canadian society in the midst of significant economic and industrial change, and of an emerging country, Canada. This context, naturally, must be borne in mind in any analysis of Cartier’s political career.

His convictions included adherence to the principles of responsible government and the parliamentary system. In Cartier’s view, the premier or prime minister and his cabinet had to bear collective responsibility to the legislative assembly for decisions made by the executive. Furthermore, ministers were individually responsible for the affairs of their departments, or ministries. Lastly, members of Parliament were answerable to their constituents for their actions. These principles remain at the core of our political system; Cartier was one of the first politicians to defend them and put them into practice.

Cartier belonged to a group of politicians who were dubbed “Reformers.” Their leader was Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine, from whom Cartier drew much inspiration—for example, in engaging in patronage. The practice, which was common at the time, consisted of appointing people close to the governing party to governmental positions. In La Fontaine’s view, this was not only about rewarding supporters; it was also “one means of entrenching the francophone bourgeoisie.”

The Reformers differed from the other political factions of the day by their constant quest for a moderate middle ground. They rejected the theses of both the Rouges and the Ultramontanists: the former hewed to radical liberalism, advocated the annexation of Canada to the United States, and were anticlerical; the latter believed that the power of the Catholic Church should take prominence over political power. The Reformers, meanwhile, sought a middle way, more likely to guarantee a stable and orderly society, with no need to resort to extreme solutions. That way consisted in allegiance to the British Crown, implementation of responsible government, and, ultimately, the co-existence of the French-Canadian and English-Canadian peoples. For these reasons, the Reformers accepted the Act of Union of 1840, despite its serious flaws, and collaborated on the project that would lead to Confederation in 1867. Clearly, to be a Reformer was above all to be pragmatic.

Property rights were another of Cartier’s core convictions. He believed property was fundamental to the organization of society. To be a property owner required good judgment, as it involved the responsibility to manage and maintain that property, a concept that could not be grasped by someone who was not an owner. Property, in Cartier’s view, conferred a degree of dignity on a person. There was nothing unjust about the notion, because anybody could aspire to own property; provided that he was prepared to put in the effort required. In other words, property was accessible to all as long as those who desired it worked hard enough to earn it.

George Etienne Cartier’s house, St. Antoine sur Richelieu, QC, copied 1912. (McCord Museum)

Cartier was a solicitor, a businessman, a parliamentarian, and a minister. He owed his career in law to the flourishing of Montreal’s industrial and commercial centre; as he put it, he was “in the right place at the right time.” The first clients of his law practice were members of his family, alumni of the Collège de Montréal, and people from his hometown. Later, his client base broadened to include entrepreneurs, manufacturers, shopkeepers, and the like. Gradually, he became part of the Montreal business community, and began to be appointed to the boards of directors of various companies. Moreover, true to his convictions, he invested part of his savings in real estate, acquiring several buildings (along Notre-Dame Street in Montreal, for example), which earned him substantial income.

Concurrently with his activities as a solicitor and landowner, Cartier took an interest in politics. He associated with former Patriotes who, like him, now favoured compromise with the political power in place, and was determined to follow in La Fontaine’s footsteps. In 1848, he made his move, standing as a Conservative candidate in a by-election in the riding of Verchères. He won by a few hundred votes.

When Cartier arrived in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada, the debate was dominated by two issues: reparations for victims of the 1837 and 1838 rebellions, and the proposed annexation of Canada to the United States. A discreet parliamentarian at first, Cartier tacitly supported La Fontaine, who was in favour of the Rebellion Losses Bill. He strongly opposed the annexation movement, led by the Rouges. In historian Brian Young’s view, Cartier’s aversion to annexation was directly related to his multiple occupations. As a businessman, he had every reason to want to maintain the status quo, namely, preservation of a British parliamentary system, because of the guarantees it offered of economic stability and a healthy climate for business. As a politician, meanwhile, Cartier had a “lifelong distrust of American democracy,” with its radicalism, and its failure to exemplify executive authority that imposed respect by everyone. The especially bloody Civil War certainly nurtured that sense of suspicion. Cartier was adept at distinguishing economic interests from political concerns, which explains why he advocated freer trade bet ween the Canadian and U.S. economies (following the 1846 repeal of the Corn Laws, with their preferential tariffs that favoured Canadian goods, Canada had an urgent need to find new markets).

Cartier the parliamentarian thus began to attract attention. Not because of his oratorical talents: it is said that he was not particularly charismatic, and given to long, tedious speeches. He was, however, recognized for his ability to persuade, which in politics is as valuable as charisma. He excelled in parliamentary commissions, where he won over colleagues with ease. In this way, he compensated for a lack of charisma with a good measure of intelligence and, above all, political instinct, which would serve him well in pushing through several significant reforms.

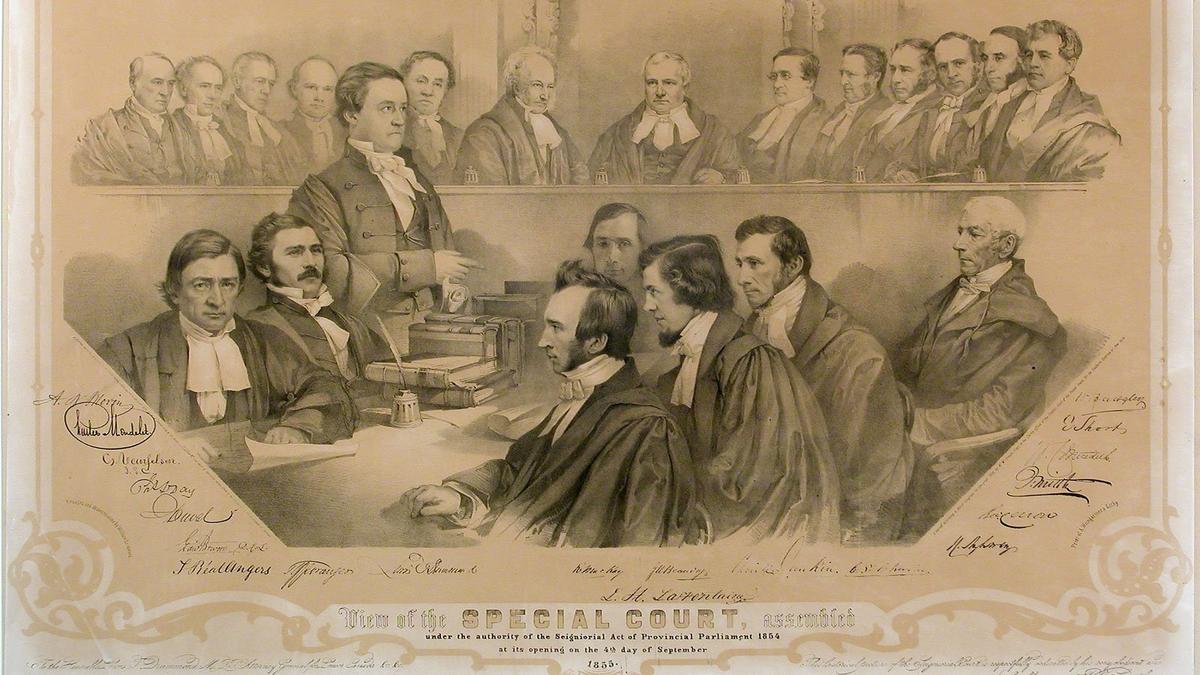

View of the Special Court, assembled under the authority of the Seignorial act of Provincial Parliament 1854. (McCord Museum)

Inherited from the French colonial era, the régime seigneurial was the basis for the organization of social and economic life in Lower Canada, with its mostly rural populace. Under this system of land tenure, every farm was part of a seigneurie, or estate, which collected dues of all kinds. For example, the censitaire who farmed the land not only had to use implements belonging to the seigneur but had to pay to use them, despite the fact that he already paid annual tax to said seigneur.

In Cartier’s view, the seigneurial system was a major hindrance to French Canadians’ economic, social, and political development. He thought the rents and dues were excessive and ill suited to the economic context of the time. And he was especially opposed to this obsolete system because it prevented, or at least considerably limited, access to land ownership, a principle that he fiercely defended.

Politically, the seigneurial system was an obstacle to the establishment of a stable state and the institution of new social, commercial, and agricultural policies necessary for economic development. Cartier played a role in the adoption of the Seigniorial Act of 1854, which abolished the system by, among other ways, convincing rural residents of the benefits they would derive from the legislation.

In 1855, Cartier was named provincial secretary for Canada East. In that capacity, he was responsible for a second major reform, that of the education system in Lower Canada. At the time, lay teachers received no professional training. Public schools were underfinanced, and there were frequent irregularities in the system. On top of this, many school principals were illiterate, and a significant number of teachers were minors. Unsurprisingly, only a small percentage of adult francophones knew how to read and write.

Cartier assigned Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau the task of assessing the situation and presenting potential solutions. After Chauveau’s study confirmed the dire state of the public education system, Cartier introduced legislation in 1856 that led to the creation of the Conseil de l’instruction publique (Council of Public Instruction), the ancestor of Quebec’s Ministry of Education. The Council’s job was to administer the public school system, and this included regulating examinations, selecting textbooks, and establishing standards of teaching.

That a body such as the Council was created, rather than a ministry of public education, was the result of a compromise, which Cartier accepted because of opposition from the Catholic Church and its allies in the conservative bourgeoisie, who wanted to retain control over school institutions, as well as from the anglophone community, fiercely committed to autonomy for their schools. Still, implementation of the Council of Public Instruction led to more schools being built and, above all, to improved literacy.

The third great reform that dates from George-Étienne Cartier’s time in government is the drafting of the Civil Code of Lower Canada. During the French colonial period, Canada was subject to the coutume de Paris, the customary law of northern France. Under this system dating from feudal times, “property rights [were] integrated into a seigneurial, family, and religious framework.”

After the 1759 Conquest of New France, however, British criminal law had been imposed, and this, combined with the later abolition of the seigneurial system, had resulted in a veritable legal hodgepodge. Cartier set up a commission tasked with codifying civil law, and chaired the parliamentary committee that studied the commission’s report. He then used his parliamentary majority to enact the new civil code, in 1866.

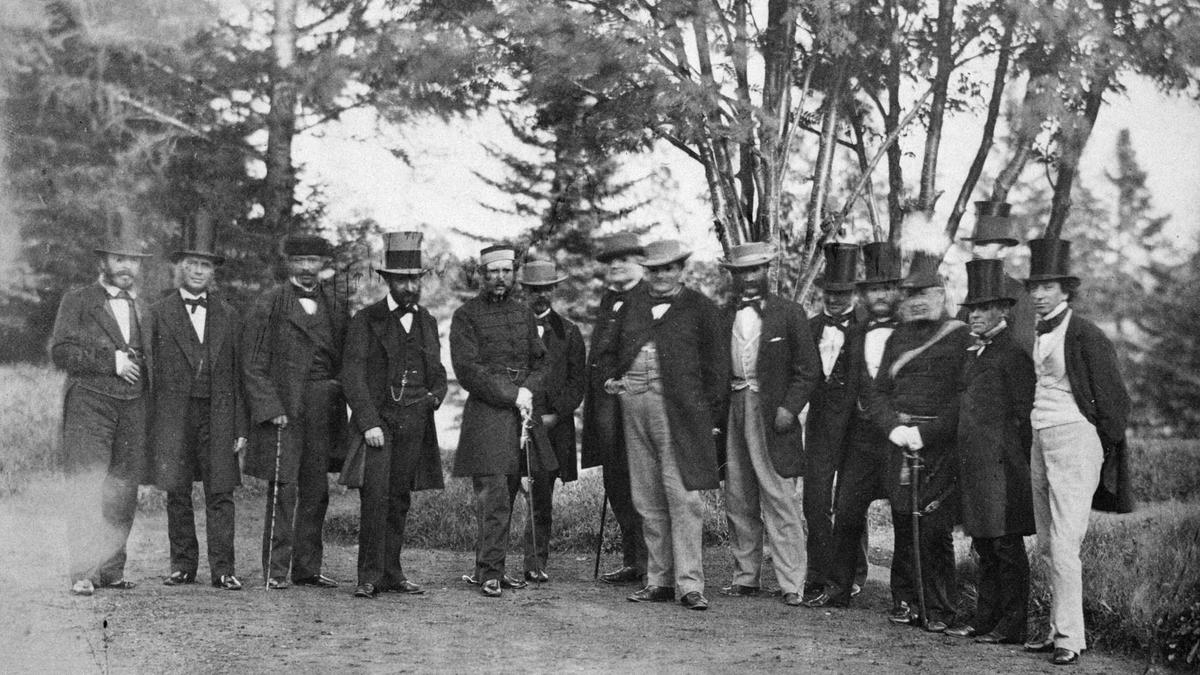

Hon. John A. Macdonald, Hon. George-Etienne Cartier and Lieutenant-Colonel John G. Irvine, among others. 1860. (Library and Archives Canada)

Between 1815 and 1851, Western countries remained in the throes of a lengthy recession, and Canada was no exception. Among possible remedies for this malaise, the idea of free trade gained increasing traction. Canadian producers no longer benefited from Britain’s preferential tariffs, so the country turned to its neighbour to the south, concluding the Reciprocity Treaty with the United States in 1854. This was only a temporary panacea for the Canadian economy, though, because the agreement would only remain in force for ten years. New markets had to be found; hence the idea of a federation between the colonies of British North America to reduce barriers to trade among them.

In addition to the commercial incentive, there were political motivations. On the one hand, imperialism was becoming increasingly less popular among the British political class: they viewed the colonies, or more precisely their defence, as a financial burden. On the other, the 1840 Act of Union, which had joined Upper Canada with Lower Canada, where the majority of French Canadians lived, had become a source of chronic political instability.

Here again, a union of all the colonies of British North America seemed the ideal solution. The partnership would thus be a political one, but motivated in large part by economic imperatives, and the building of railways would be its guiding enterprise. Contrary to the opinion of some observers, in particular those who defend the principle of duality, Canada resulted not merely from a political union between two nations, French-Canadian and English-Canadian, but from an economic union of four colonies: Ontario, Quebec (formerly United Canada), New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. George-Étienne Cartier was to play a pivotal role both in the establishment of Confederation and in the building of the great railways that would serve as the new nation’s backbone.

Cartier and the railway companies had an extensive history. He had long advocated construction of a rail link between Montreal and the eastern coastal cities of the United States, to ensure year-round connections to seaports. In this, Cartier showed great foresight: winter ice brought maritime transport within Canada to a standstill six months a year, and permanent access to ports on the U.S. east coast would be a boon to the country’s economy. Moreover, a modern transportation net work would prevent American interests from gaining a trade monopoly in the Canadian West. So while the annexationists represented a real threat, at the same time, some sort of rapprochement with the United States was essential—at least in economic terms.

In 1848, during his earliest days as a member of the Legislative Assembly, Cartier petitioned the government to support the St. Lawrence and Atlantic Railway company, then attempting to complete its line connecting Montreal with Portland, Maine. He secured passage of a bill recognizing the principle that the government should subsidize railway construction. More specifically, the Guarantee Act stated that the government had to contribute financially to construction or extension of any line more than seventy-five miles long. Meanwhile, Montreal businessmen, sensitive to Cartier’s argument that the country’s political and economic destiny was dependent on railway construction, succeeded in raising enough money to build the stretch of track that would secure the government guarantee. In 1853, Cartier was invited to ride on the inaugural train between Montreal and Portland.

By the summer of 1864, the Parliament of United Canada was in the midst of a fractious session. George Brown, the leader of the Clear Grits, a group of radical liberals that held the balance of power, proposed a coalition government with the Conservatives to remedy the situation. Brown imposed a condition, however: the government must adopt a new constitution. The Conservatives, led by Macdonald and Cartier, were amenable to this, even agreeing to discuss a federal union. The idea had been around for years, but both opportunity and political will, in all likelihood, had been lacking.

The leaders of United Canada learned that the representatives of the maritime colonies—Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick—were to meet at Charlottetown in September to discuss a possible union. They seized the opportunity and arranged to be invited to the conference as observers. Better prepared, the United Canada delegation convinced the other provinces of the advantages of federating all of the British North American colonies. It is likely that Cartier’s persuasive skills, which he had continued to hone over the years, helped make the case for a broader union.

The representatives of United Canada and the Maritimes met for a second conference, in Quebec City in October 1864, which led to an initial agreement in principle. At this meeting, Cartier was a discreet presence. Historian Jean-Charles Bonenfant’s explanation is that the delegates were busy studying Macdonald’s proposals, prepared ahead of time by the cabinet of United Canada, to which Cartier belonged.

He therefore focused instead on defending the measures that he believed were necessary to protect the interests of Lower Canada—that is, of French Canadians.

The delegates reached agreement on a number of essential points. Representation of each province in the future House of Commons would be in proportion to its population, while in the Senate, each would have an equal number of seats. There was a commitment to build an intercolonial railway to unite Quebec and Ontario with the Maritime provinces, so that Canadian goods would no longer have to transit through the United States. There is no doubt that Cartier provided the impetus for that project. The agreement became known as the Quebec Resolutions, also referred to as the Seventy-Two Resolutions. After approval by the provincial legislatures, the text of the proposals was submitted to the British government. It served as the draft for the British North America Act.†

Though some of the colonies had misgivings as to the content of the Seventy-Two Resolutions, a Canadian delegation set sail for London in late 1866 to put the finishing touches on the legal text to be presented to the British parliament. At least one account claims that John A. Macdonald used these final negotiations to attempt to change the federative system agreed upon in Quebec City into one that would concentrate power in the hands of the central government. Cartier, proponents of this view say, opposed this, having grasped the scope of Macdonald’s plan. To him, it would have been unimaginable that the federal government should appropriate the greater share of power, including jurisdiction over education and law, which were in the hands of the future provinces, per the reforms that Cartier himself had championed. In his view, the existence of French-Canadian political, social, and cultural institutions could not be subjected to any political compromise. The French Canadians were maîtres chez eux.

They constituted a full-fledged nation that was joining a broader economic and political union of its own volition. And that union, the Canadian federation, would ensure not only the survival of the French Canadians—including those living in the newly created province of Quebec—but also their development as a francophone people within North America.

The new Canadian constitution was submitted to the British parliament in February 1867, as a bill introduced in the House of Lords. It received royal assent in March, with a proclamation issued by Queen Victoria in May, and came into effect on July 1.

Cartier returned from London with a sense of duty fulfilled. From then on, he was among the men who would become known as the Fathers of Confederation. It was also around this time that he was made a baronet, according him the title “Sir” before his first name. In addition, he secured a twelve-million-dollar guarantee for construction of the intercolonial railroad. But rail development was no longer merely a matter of connecting Quebec and Ontario with the Maritimes. From then on, the federal government, and Cartier in particular, would concern itself with Canada’s westward expansion, and the key, once again, would be the construction of “iron roads.”

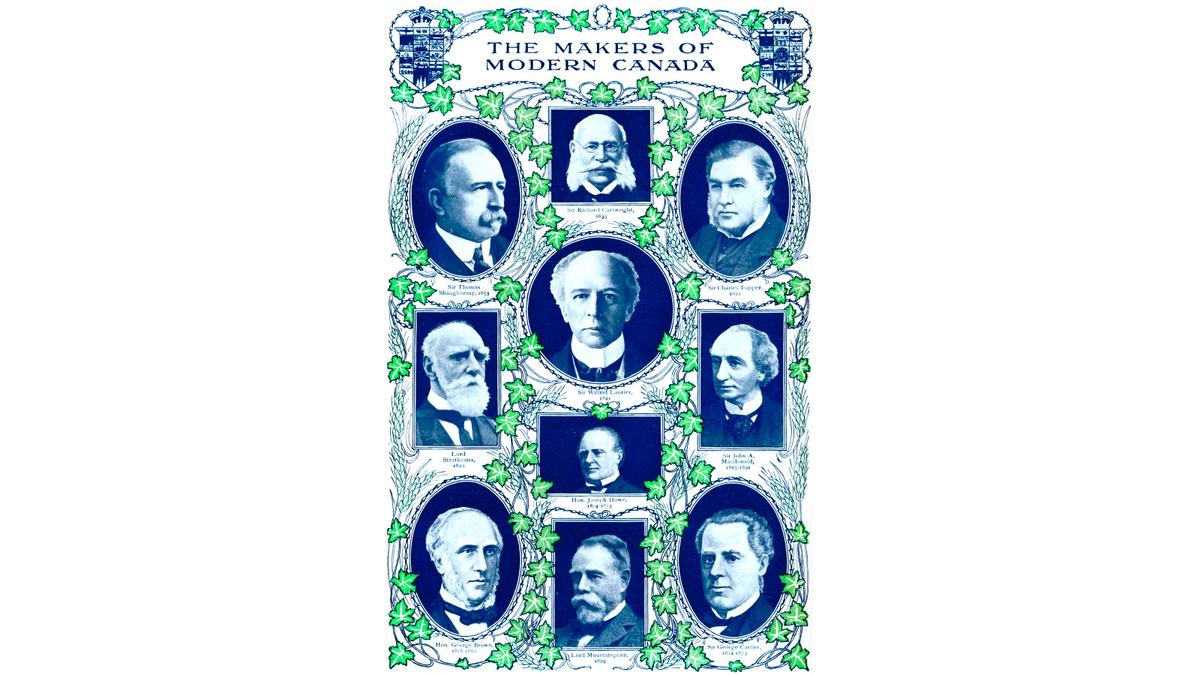

The makers of modern Canada, 1909. Sir Thomas Shaughnessy, Sir Richard Cartwright, Sir Charles Tupper, Lord Strathcona, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Sir John A Macdonald, Joseph Howe, George Brown, Lord Mount Stephen and Sir George-Etienne Cartier. From Harmsworth History of the World, Volume 8, by Arthur Mee, J.A. Hammerton, & A.D. Innes, M.A. (Carmelite House/The Print Collector/Getty Images)

Aside from his new duties as minister of militia and defence, whereby he reorganized the country’s system of defence, Cartier was to dedicate the remainder of his political career to extending the territory of Canada all the way to the Pacific Ocean. He travelled to London to negotiate Canada’s purchase of Rupert’s Land and the North-West Territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company and the British government. Canada was on the way to becoming one of the world’s largest countries. Cartier was the man who organized these new territories. He reached agreement with the Métis, who inhabited a significant swath of the newly acquired land, on the creation of a new province, Manitoba, in 1870. And it was largely thanks to him that British Columbia became Canada’s sixth province in 1871, in return for the federal government’s pledge to complete what became known as the Canadian Pacific Railway, which in 1885 at last linked the country from coast to coast.

Cartier’s connections to the railway companies, including the Grand Trunk, epitomized the alliance between economic interests and the Canadian government: while the government instituted tariffs, determined the rights-of-way, defined the labour-market regulations, and so on, the railway companies financed election campaigns and provided work for politicians like Cartier. It was thus a mutually beneficial system, and common practice at the time.

In the 1872 general election, Cartier was unseated by a first-time Liberal candidate in the riding of Montreal East, after representing it for eleven years. The defeat would leave a bitter taste. He was quickly elected by acclamation in the Manitoba riding of Provencher, though, after Métis leader Louis Riel withdrew his candidacy.

But Cartier wasn’t out of the woods yet. Before long, it was alleged that he and Macdonald had solicited campaign donations from a Montreal businessman in exchange for the awarding of the contract to build the transcontinental railway. Weakened by chronic nephritis (inflammation of the kidneys), Cartier left Macdonald to defend the government against the charges. The affair escalated into the so-called Pacific Scandal, which forced the Conservatives to resign. In the meantime, Cartier had left for London, hoping his health would improve. It did not: he died on May 20, 1873, in the city he had always been so fond of.

There are two great thrusts of George-Étienne Cartier’s career that ensured his legacy as a pre-eminent figure in Canadian history: the notion of duality, and economic development. These lines of force intertwine to describe the singular journey of a man as well as of a people whose future he helped shape in durable fashion.

Cartier embodies a certain vision of Canada: the union of the French-Canadian nation, or Quebec, and the English-Canadian nation, or the rest of Canada. Today, though, that idea of duality appears to have lost its lustre. The narrative to which many Canadians, and in particular French Canadians, choose to refer in seeking to understand their country does not seem to have the same persuasive power.

There appear to be two reasons for this. First, duality obscures the existence of other Canadian nations, not least the Acadians and the First Nations. It is thus a non-inclusive vision. Not only does it overlook those other founding nations, but it also slights populations of immigrant origin. Moreover, duality implies a Canada made up of two distinct blocs, whereas it is, in fact, anything but. One need only consider the provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, which were initially colonized by francophones. The Métis in this region would never have identified themselves with a monolithic “French-Canadian” nation.

Although the traditional definition of Canadian duality can be called into question for these reasons, the concept has not exhausted its potential. We must, however, conceive of it differently. We therefore propose a definition based on the following fact: the French-Canadian nation, today embodied primarily in Quebec, predates the nation of Canada. In other words, its institutions, culture, and language existed before the nation of Canada. This is an important fact of history, all the more so because it nurtured the political journey of George-Étienne Cartier.

The notion of duality is evident in the Cartierist view in at least two areas. The first has to do with the reforms that he championed. For example, although Cartier campaigned in favour of its abolition, the seigneurial regime left a durable imprint on Quebec: it is the only Canadian province where farmland was divided into rangs, or long, narrow strips perpendicular to waterways. This is a significant indicator of difference vis-à-vis the other provinces, as the seigneurial system was one of the first methods of land-use planning in the country, if not the first. The difference is especially important when one considers that geography is a fundamental identifier for a people.

There was an even more important reform, though: that of the law. In addition to having had the loi coutumière system before the 1759 Conquest, Quebec is today the only province with a civil code—that is, a body of rules set down as general principles governing rela- tions between persons, which differs from the British common law, under which the courts base decisions on jurisprudence. Thus there has been a system of law specific to French Canadians—at least in Quebec—both before and after the Conquest. It is significant to note that Canadian law today is characterized by a form of bijuralism—the coexistence of two distinct legal traditions—which confirms that there is at least one form of Canadian duality.

The second area in which Cartier illustrated duality was his political positions in favour of French Canadians, in particular when it came to constitutional negotiations. His opposition to Macdonald’s centralist designs and his unwavering defence of French-Canadian institutions strongly suggest that he would never have agreed to Quebec’s joining the Canadian Confederation without existing French-Canadian institutions being accepted by all parties. In other words, the French Canadians had to remain maîtres chez eux. This was non-negotiable.

Cartier’s pressing for a federation less centralized than the one Macdonald sought also reminds us of two lessons about the country’s origins and, concomitantly, about duality.

First, the Fathers of Confederation agreed on the creation of a federal state, not a unitary state. French Canadians in general and GeorgeÉtienne Cartier in particular would never have accepted a Canadian state that failed to take into account the existence of a historically constituted French-Canadian nation. Quebec joined the Canadian federation first of all because it obtained the guarantee that its distinct character would be respected and recognized by the other members of that federation, and second, because it also secured the right to renegotiate the conditions of its membership in the federation should it come to consider that its distinct character was no longer respected and recognized by the other provinces. In short, it would have been inconceivable for Canada to be created to the detriment of the distinct character of the French Canadians, in particular the Québécois. Let us note that this conception of duality does not cast doubt upon the explanation provided previously, that an economic union was key to the building of Canada: it is complementary to it.

Second, whether we conceive of the origin of Canada through the prism of duality, economic union, or both, one fact is incontrovertible: Canada was not a creation of the Canadian state, but of the colonies of British North America, including the French-Canadian nation. It was not the central government that decided to unite the colonies, but the colonies that united to create a federal state. In this respect, the provincial governments are subordinate neither in fact nor in law to the federal government. The two levels of government are autonomous in relation to one another, especially when it comes to their respective spheres of competence. This justifies, for example, the federal government’s acknowledgement of jurisdictions—cultural, institutional, political, and so forth—specific to the provinces, in particular those specific to Quebec, by means of tools such as asymmetrical federalism. Thus it is the provinces, including Quebec, that cement Canadian unity.

Economic development is another essential aspect of the history of Canada and, as we have noted, a key path in Cartier’s political journey. Consider his speeches aimed at persuading citizens of the benefits of doing away with the seigneurial system, or his activism in favour of railway construction—especially given that one of the primary motivations for the creation of Canada was the unification of a group of colonies for economic reasons.

In our opinion, economic development has a bearing on three fundamental aspects of Canadian federalism. The first is liberty: for a people to have the liberty of self-determination—and thus of making its own choices—it must first control the economic levers proper to a state, such as the provision of public finances and maintenance of a social and political environment conducive to wealth creation. That is all the more important in a country such as Canada, in which the provincial governments manage the social safety net (hospitals, education, social benefits, and so on).

That same liberty—this is the second aspect—enables a province such as Quebec to exercise its full autonomy in its own spheres of competence. We also note that it is easier for a province to negotiate a new constitutional agreement when its public finances are sound.

The final aspect involves the idea that an economy is not an end in itself, but a means to an end, which is the overall welfare of individuals and communities. It provides for what the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor has called “the affirmation of ordinary life”—that is, family life and production. Thus economic development procures for a people the freedom to determine its future and the capacity to improve the terms of the union of which it is a part, in order for it ultimately to ensure the welfare of the greatest possible number of citizens.

Jean Charest, the former premier of Quebec, and one of the authors of this essay. (CP)

George-Étienne Cartier and the other figures whose lives are related in these pages were conveyors of a shared destiny: that of the French-Canadian nation, embodied essentially by Quebec. That shared destiny is first and foremost a shared language. French is not merely a tool for communication, an instrument for a particular purpose, but a way of existing—in other words, of being in the world. That shared destiny is also a history, stretching back to the “discovery” of a new world, America, and continuing through to the founding of the Canadian federation. That history allows us to measure the scope of everything accomplished since, including the common good that is Canada.

Our internal quarrels, in particular in Quebec, tend to cast a veil over the things that unite Quebec and Canada. That unity illustrates that our country is marked by profound diversity—cultural, linguistic, and geographical—the occasionally precarious fulcrums of which were, in many cases, erected and maintained by francophones like George-Étienne Cartier. Canada has allowed Quebec to progress from survival to development, to become a nation in its own right that—if we may be so bold—exercises sovereignty over the essential spheres of the lives of Quebeckers.

A final aspect of that shared destiny is institutions. Quebec is distinguished by a British-inspired parliament that bears a French-inspired name, the National Assembly, by a tradition of civil law paired with British common law, and by a pattern of land management that is unique in North America. Each of these institutions operates in one and the same language and is the fruit of a singular history. These institutions are the culmination of the destiny common to all French Canadians, particularly Quebeckers.

There are men whose life stories overlap with a larger history, that of their country. George-Étienne Cartier’s story is one such dual narrative. Through the reforms undertaken under his leadership, the building of railways, the constitutional negotiations, the addition of vast territories, and the creation of new provinces, Cartier played a pivotal role in the creation of Canada. Few people accomplish so much in the span of a lifetime. Cartier is part of the pantheon of Canada’s great nation builders. We owe him a great debt. And the best way to repay it is to become acquainted with his life story.

Excerpted from Legacy: How French Canadians Shaped North America. Copyright © 2016 by Generic Productions Inc. “Sir George-Étienne Cartier” © Jean Charest and Antoine Dionne-Charest. Published by Signal, an imprint of McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Web producer: Adrian Lee

Published: June 27, 2017