Bay du Nord: The $16-billion oil project that could make or break Newfoundland

The province’s next offshore oil megaproject is either a salvation, a betrayal or the future of Canadian oil. It might be all three.

Share

March 2, 2023

A journey from downtown St. John’s to the Flemish Pass will take a traveller nearly 500 kilometres into the North Atlantic—one-sixth of the way to the shores of Ireland. Along the way they’ll pass through ruthless storms, towering waves and the paths of massive icebergs drifting from the Arctic Circle. Plunge below the surface, however, and there’s a bounty to be found.

The Pass is a deep basin carved into the ocean floor, under which lies at least 500 million barrels of recoverable oil, first discovered in 2013 by the Norwegian oil and gas firm Equinor. Today, the company plans to open this inhospitable seascape to the most ambitious offshore-oil undertaking in Canadian history.

In the expedition-heavy language of the oil industry, Equinor has dubbed the Flemish Pass a “new frontier” in deepwater oil, farther to sea than any prior offshore project in Canada. Workers will live and work here on a platform floating above open-ocean waves, above a production area spanning nearly 5,000 square kilometres. They’ll extract oil from wells more than a kilometre below the water’s surface. The $16-billion project, to be called Bay du Nord, will be majority-owned by Equinor, with BP holding a smaller stake. It comes loaded with superlatives: deepest, farthest and, as Equinor is keen to claim, cleanest. The company estimates that extracting a barrel’s worth of oil from Bay du Nord will produce eight kilograms of carbon dioxide. That’s far less than the bitumen produced in Alberta’s oilsands, some of which comes with a per-barrel footprint of more than 100 kilograms, thanks to the energy-intensive extraction and refining it requires.

Bay du Nord’s reservoirs of light crude are also part of a development tradition older than Canada itself, one the country was built on: step far into nature, fell this timber, fish these waters, extract this oil and there will be prosperity. There are few places in Canada where that economic dependence on the natural world is still as starkly pronounced as in Newfoundland. Largely rural, surrounded on all sides by the sea, this is a place where many of the mainstays of 21st-century economies have been slow to take root. The only real flash of wealth in Newfoundland’s modern history was the brief, oil-fuelled boom of the late 2000s. That’s why, in a world increasingly moving toward decarbonization, Newfoundland is beating an opposite path. In 2018, the province pledged to double oil production within a decade. Two years later, after a rally in support of the oil industry in St. John’s, Premier Andrew Furey bluntly told reporters, “There is no future here without it.”

For Bay du Nord’s opponents, including environmental activists and Indigenous communities who’ve spent years fighting the project, the future is exactly the point. Ian Miron is a lawyer with the environmental group Ecojustice, which has lobbied against Bay du Nord. “Our federal government says that it understands climate science,” he says. “So it should understand that Canada can’t be a climate leader and approve fossil-fuel infrastructure projects like this one.”

That’s to say nothing of the more localized hazards. In lockstep with Equinor’s language of frontiers and discovery is a language of danger: of unpredictable conditions at sea, chemical waste, spills, leaks and blowouts. The history of Newfoundland’s offshore is littered with accidents, tragedies and disasters. As recently as 2018, Husky Energy’s SeaRose project spilled 250,000 litres of oil into the Atlantic—the largest such incident in the province’s history.

For most Newfoundlanders, however, the environmental risks and threats to life and limb pale in comparison to other risks: of poverty, crumbling infrastructure, outmigration. To them, Bay du Nord represents a promise—that this is a place where the good life is still possible.

It was the good life that drew Amanda Young offshore. Young, who’s 40, grew up in Corner Brook, in western Newfoundland, where her father was a fisher and lobsterman. During her childhood, in the 1980s, Newfoundland had yet to produce a drop of commercially viable oil. Instead, companies from Canada and abroad, including Mobil, Chevron, Husky and Petro-Canada, were jockeying to drill exploration wells, especially in the basins of the eastern Grand Banks, the vast chain of underwater plateaus known for centuries as one of the planet’s richest fishing grounds.

The province’s economy was stable but sluggish, with unemployment rates that hovered above 15 per cent, around double the numbers nationwide. The province’s economic identity was still rooted in the fishery that had sustained it for centuries—until 1992, when Young was nine. That year, the federal government imposed a moratorium on the province’s cod fishery, to preserve fish stocks that had become dangerously depleted thanks to a variety of factors: bigger and faster fishing vessels, new technologies that allowed more fish to be caught at once, and an influx of international fishing off the Grand Banks. The moratorium created a sharp dividing line in Newfoundland’s modern history. It put more than 30,000 people out of work, ended a way of life rooted in five centuries of history and rendered centuries-old communities economically obsolete.

In the next decade, the province experienced a net loss of nearly 60,000 people to other provinces—more than 10 per cent of the total population, which was then fewer than 600,000 people. Young’s father was nearly one of them. He even bought a plane ticket to Alberta, before getting hired at the last minute onto a boat fishing for herring and mackerel.

But even as the province wrestled with the economic disaster unfolding on land, something else was happening offshore. In 1997, the first commercial oil trickled in from the Hibernia fields on the Grand Banks, where Chevron had discovered promising deposits in the ’70s. The trickle soon became a torrent. In 2002, the province produced, for the first time, more than 100 million barrels in a single year. As global crude prices soared from barely $20 a barrel in 1998 to more than $120 in 2008, oil royalties helped wean the province off the equalization payments—federal transfers intended to reduce fiscal disparities between provinces—that had sustained it for years. In 2008, unemployment reached a 30-year low. For the first time since the ’70s, the province was growing, welcoming newcomers and its own expats, many returning home from Alberta’s oil fields.

St. John’s Harbour was busier than ever with drill ships and supply boats. High-end restaurants filled vacant storefronts downtown. The median house price in the province shot from under $100,000 in 2000 to nearly $300,000 a decade later, sparking big-city-style bidding wars.

Around this time, Young returned from culinary school in Prince Edward Island. She spent the next few years working at a restaurant in St. John’s, making $14 an hour and sharing an apartment with four roommates. In her off-hours, she started researching nursing school—Newfoundland’s population, the oldest in Canada, made elder care a likely growth industry. But talk of oil soon drowned that out. One day at work, a colleague mentioned the money to be made offshore. Young investigated the qualifications she’d need: first aid, safety courses, helicopter safety training for journeys to and from rigs.

She knew working offshore had its risks. In 2009, she witnessed a co-worker’s grief after a family member was one of 18 people killed when a helicopter, en route to a production platform on the Grand Banks, malfunctioned and plunged into the ocean. Still, in 2012 she walked into the offices of the catering company that contracted to oil companies and said she was a chef, ready to work. She was offshore two days later.

Young worked on the Terra Nova and SeaRose platforms on three-week rotations. She cooked and baked, and the relationships she formed with colleagues were nearly familial. She spent more time with them than with many family and friends, day in and day out.

And she was flabbergasted by the money. “It changed my life, drastically,” she says. She got her own apartment, paid off her student loans and then bought her own house in St. John’s, without a partner or family help. “The offshore provided me a great sense of independence.”

In a province that’s faced chronic underdevelopment, where the trappings and comforts of modern consumer life have been harder to come by than almost anywhere else in Canada, oil has changed lives. Robert Greenwood is director of the Leslie Harris Centre of Regional Policy and Development at Memorial University, which researches economic and social policy in Newfoundland. “Based on what people want, oil has been an unmitigated benefit for Newfoundlanders,” he says.

Greenwood can speak to that from personal experience. In the 1970s and ’80s—years before the offshore was producing commercial oil, when oil companies were still drilling exploratory wells—he worked on rigs to support his mother after his parents divorced. In 1982, Greenwood was on the Ocean Ranger, a platform on the Grand Banks owned by Texas-based Mobil Oil. That February, he was sent to Texas for training. On the way to the St. John’s airport, his taxi driver said something about a rig in trouble. When the plane landed in Houston, another passenger, also an oil worker, called home on a payphone. He hung up, called Greenwood over and broke the news: caught in a cyclone, the rig had been battered by 110-foot waves and 100-knot winds. All 84 crew members died in the sinking or after their lifeboats capsized in the frigid North Atlantic. In the heat and humidity of the Texan airport, the news of their deaths felt almost unreal. After his training, Greenwood went to New Orleans and drank for three days. Then he went home, and soon was offshore again.

“You do what you’ve got to do,” he says. “I went back to the platforms because I needed the money. Oil has been an inextricable part of my life.”

In 2014, an oversupply of oil on world markets sent prices plummeting. Canada’s energy sector was in crisis, and investment in both Alberta’s oilsands and Newfoundland’s offshore slowed dramatically. The following year, Newfoundland’s population hit a 21st-century peak of 528,000—then began to drift downward again. Again, the spectre of outmigration hovered like a dark cloud over the province.

Conor Curtis was born in 1992, the year the cod moratorium was implemented. He grew up in Corner Brook, Newfoundland’s second-largest city, with a population of 20,000 people, and saw the moratorium’s impact throughout his childhood. Today, as head of communications with Sierra Club Canada, he’s an adamant opponent of Bay du Nord on environmental grounds—but he understands why that feeling isn’t commonly shared in his home province. “The trauma of something like the moratorium, it continues on in communities, across generations,” he says. “It’s a feeling that things could fall out from under your feet at any moment.”

The oil boom rescued many from that feeling, only to plunge them back into it when it came crashing down. But even today, in its diminished state, the industry remains a behemoth. In 2021, it accounted for nearly one-third of Newfoundland’s GDP, more than four times as much as real estate and health care, the next largest industries. It employs 3,000 people directly and 20,000 indirectly. And it is, in Greenwood’s words, “the crack cocaine” of government revenue.

In 2012, when Amanda Young first ventured offshore, oil royalties accounted for nearly 40 per cent of the province’s $8.6-billion revenues. By last year, in which the province posted a $400-million deficit, oil accounted for a still-considerable 10 per cent. To cut oil out of the provincial budget, says Greenwood, is a non-starter: “It’s like, what part of the children’s hospital would you like to close?”

Then came Bay du Nord. In 2018, the province announced plans to develop the reserves that Equinor and its then-partner, Husky Oil, first found in 2013. Expectations were big: the provincial government estimated the project would create more than $14 billion in economic activity, ensure 22 million work hours and provide $3.5 billion in government revenues. That, in turn, would set Newfoundland apart as what the provincial government calls a “deepwater centre of excellence,” thanks to the sophisticated engineering and technical requirements of the project.

Equinor has a long history with dangerous, difficult offshore conditions. It was formed in 2007 from the merger of Norway’s state-owned Statoil and the oil and gas division of energy company Norsk Hydro. Statoil helped open Norway to exploration in the ’70s, where severe and unpredictable weather posed many of the same challenges found in the Flemish Pass.

Should Bay du Nord go forward, some of its roughly 40 wells will be drilled to 1,170 metres below the waves—almost 10 times the depth of the province’s second-deepest project, the SeaRose, which sits at a comparatively shallow 120 metres over the Grand Banks, west of Bay du Nord. Drilling into the seabed will require workers to connect steel pipes, each about 30 feet long and weighing 600 pounds, into a column known as a “drill string,” descending all the way to the ocean floor. At the bottom, a boring device will cut into the seabed, pushing deeper as the string grows. On the ocean floor will be a “blowout preventer,” a series of clamps that closes the pipe to prevent explosions of oil that can occur when pressure builds too high.

A blowout is only one of the environmental hazards at play with a project as large and remote as Bay du Nord—there are also risks of leaks, disturbances to underwater ecosystems and collisions between supply ships and marine life. In 2019, Equinor submitted its environmental impact study to the federal government, outlining those potential risks and mishaps, along with its plans to prevent them and deal with spills or other problems should they occur. Two years passed as analysts with the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada parsed Equinor’s submission, returning to the company to ask for new information and amendments. In July of 2020, Equinor submitted a revised, 434-page report. It concluded neatly: routine operations will be unlikely to result in adverse environmental impacts. The federal government’s decision—to approve or not—was expected that same year.

The province and trade unions lobbied government hard for approval, waging a PR campaign to win over Ottawa. For them, Newfoundland’s very future hinged on a green light. There was risk in a long delay—that investors could get cold feet and think Canada’s regulatory atmosphere inhospitable, leaving the development unviable even if it was approved.

In September of 2020, with the Impact Assessment Agency still deliberating, Bay du Nord proponents organized a rally in support of the oil industry on the steps of St. John’s Confederation Building. Dave Mercer, then-president of Unifor chapter 2121, gave a speech to the hundreds-strong crowd about his time working on the Hibernia rig. Mercer is a material controller, who assists in loading and unloading materials on production platforms. He spoke not only about Bay du Nord, but about the oil bust and pandemic stresses that had cost thousands of jobs in Newfoundland since 2015. He listed offshore projects that had experienced layoffs: Hibernia, Terra Nova, SeaRose, Hebron. In the preceding five years, more than 6,000 oil-industry employees lost their jobs. “The financial burden is overwhelming for so many,” he said. “House payments, car payments, childcare, after-school activities, college, university, are now on hold.”

Amanda Young spoke next. “We’re asking our government for a hand up, to work with us, listen to us,” she said. “Sit down with the companies and negotiate a deal. Most importantly, figure out a solution that keeps the people of Newfoundland and Labrador working in this province.”

Privately, Young had grown pessimistic. She had been laid off from Terra Nova and didn’t know when or if she would be going back to work. She had opened her nursing school application again, and thought she might have to sell her house and start again in a new career—then with a partner and two stepchildren—right as she was about to turn 40. It was a terrifying prospect.

As the federal government deliberated, the context around the project, and Canada’s oil and gas future, kept shifting. In the fall of 2020, oil prices began rallying from the steep drop at the beginning of the COVID pandemic, improving the economic outlook for the industry. At the same time, talk of more rapid transitions away from fossil fuels entered the mainstream. In May 2021, the International Energy Agency—the Paris-based advisory organization that produces forecasts and reports relied on by the global energy industry—issued a special report stating that developing new oil and gas deposits was incompatible with keeping global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius, as advocated by the Paris Agreement, to which Canada is a signatory. “If governments are serious about the climate crisis, there can be no new investments in oil, gas and coal, from now, from this year,” IEA executive director Fatih Birol told media.

The report sparked new debate about the future of Canada’s oil and gas assets. “It’s always been bizarre logic to me, the idea that because Newfoundland is so dependent on oil and gas, it should take the longest to transition,” says Conor Curtis. It’s exactly those economies and communities most dependent, he says, that should be moving faster than everyone else to change.

Meanwhile, the federal government’s decision kept getting pushed—first to December of 2021, and then again to March of 2022. Final approval for Bay du Nord lay, ultimately, with Environment and Climate Change Minister Steven Guilbeault, once nicknamed the “Green Jesus of Montreal” for his uncompromising environmental activism. In 1993, in his early 20s, he co-founded environment and agriculture non-profit Équiterre. He later joined Greenpeace, heading its climate change division. In 2001, he climbed 340 metres up steel maintenance cables hanging from the CN Tower to hang a banner reading “Canada and Bush climate killers.” His appointment in 2021 as environment minister was poorly received by many in the energy sector—as well as by politicians who had appointed themselves the industry’s defenders. “His own personal background and track record on these issues suggest somebody who is more of an absolutist than a pragmatist,” said Jason Kenney, then premier of Alberta. “I hope I’m wrong about that.”

As it turns out, he was. When Guilbeault took office, his official biography dubbed him “a pragmatist who works to make a difference by building bridges”—quite a pivot from his days as an environmental radical. Still, given his history, opponents of Bay du Nord hoped he would make a stand and reject the project, regardless of the Impact Assessment Agency’s recommendation. Guilbeault has the power to exercise what is known as ministerial discretion, to overturn any recommendation if he desires, even if it contravenes broader consensus.

That hope was bolstered in January of 2022, two months before the decision was due, when the Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat—a group of federal scientists who provide advice and peer review to Fisheries and Oceans Canada, or DFO—released its own independent review of Equinor’s environmental submission to the federal government. Its takeaways were damning.

The report outlined what it characterized as omissions and mischaracterizations in Equinor’s submission. It said the company had downplayed the potential for ship strikes with marine animals. It said the possibility of an “extremely large spill” was 16 per cent over the project’s lifetime, despite Equinor’s impact statement referring to it as “extremely unlikely.” It oversimplified the effects of a blowout, failing to heed the lessons of the Deepwater Horizon disaster in 2010 that killed 11 workers and spilled 134 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. Spawning grounds for capelin, an important Newfoundland fish species, would be threatened, which would have knock-on effects on endangered species including American plaice and killer whales, which feed on them. A blowout could lead to slicks of oil spreading across sensitive areas of coral and sponges and damage shrimp and cod habitats.

The review ultimately concluded that Equinor’s submission wasn’t a credible source of information. Though the report for the DFO was responding to Equinor’s 2019 environmental impact statement, not the revised 2020 version, Curtis and other critics say Equinor’s revisions still didn’t come close to addressing the concerns outlined.

Montreal-based environmental lawyer Shelley Kath—who did consulting work with Steven Guilbeault in his Équiterre days—was commissioned last year by an environmental organization called stand.earth to analyze the report’s findings. She concluded that Equinor’s revised impact statement, used as the basis for the federal approval, failed to address many of the DFO scientists’ critiques. It continued to underestimate the potential for ship strikes with marine mammals (like whales), mischaracterized the effects of oil spills on marine life and, perhaps most significantly, downplayed the potential for a major oil spill. Equinor’s final revised impact statement continued to refer to a large spill as “extremely unlikely,” despite that 16 per cent likelihood.

“That just on its face gives one a queasy feeling,” says Kath. “A sense of the proponent not taking the criticisms seriously.” Kath points out that a spill in the Flemish Pass, in the inner branch of the Labrador Current, could rapidly spread oil southward through waters rich with marine life.

In March of 2022, more than 200 environmental groups across Canada and worldwide jointly called on Guilbeault to reject the project. That same month, Sierra Club Canada held a media briefing on Bay du Nord. “The world is changing, and climate change is already here,” said Amy Norman, an Inuk environmental activist from Labrador, during the event. “Already we’re seeing impacts here in Labrador and in Newfoundland. Unreliable sea ice, warming temperatures, more frequent storms, unpredictable weather. It’s already impacting our ways of life, and it’s already changing how we live on these lands.”

That reality was thrown into relief last fall, when Hurricane Fiona hit Atlantic Canada. The storm caused more than $800 million in damage, washing away buildings and killing a woman from the town of Port aux Basques, who was swept out to sea along with the contents of her home. The damage, of course, was to be repaired with money from the same provincial coffers to which Bay du Nord is to contribute.

On April 6, the decision finally came down: a green light. Guilbeault declined interview requests for this piece, but in a press release, he implied that this project would be different, held to a laundry list of 137 binding conditions—the strongest ever, he claimed. The government touted its relative greenness, which went beyond its low per-barrel emissions. As a condition of approval, the project will have to achieve net-zero status by 2050, meaning that all of the planet-warming greenhouse gases produced in its operations will have to be offset or captured by carbon-capture technology. On the same day Bay du Nord was approved, the federal government announced that every future fossil-fuel project approved in Canada will also need to achieve net-zero emissions. That makes Bay du Nord not just the next big thing for Newfoundland and Labrador, but a turning point for Canada’s fossil-fuel business—an attempt to position it as a sustainable industry fit for a greening world.

To the project’s opponents, that’s a very, very small victory. The emissions to be offset are what are called upstream emissions, produced during the extraction process itself. But the vast majority of a barrel’s carbon footprint comes from downstream emissions, when the oil is burned in a car or a power plant. Those emissions don’t count against the net-zero designation.

A month after approval, the group Ecojustice, on behalf of Équiterre and Sierra Club Canada, filed a lawsuit against the federal government, arguing it had failed to consider how downstream emissions will contribute to Bay du Nord’s environmental impact. If it had, the suit alleges, the project would contravene Canada’s international obligations to fight climate change. Eight Atlantic Canadian Mi’kmaw communities later joined the suit.

“It’s great to reduce emissions,” says Sierra Club’s Conor Curtis, “but reducing upstream doesn’t do much. Basically, it means we’re not talking about a net-zero project.” Instead, he suggests, the stringent conditions on Bay du Nord are an attempt to reconcile Canada’s self-image as an environmental leader with its economic interest in a project that will pump hundreds of millions of barrels’ worth of oil into the atmosphere. It’s “an act of extreme climate hypocrisy,” he says.

Of course the same could be said of any oil and gas project. The argument made for Bay du Nord is about relative impact: oil and gas won’t disappear overnight, so steps in the right direction, like those 137 binding conditions placed on Equinor, are better than nothing at all. Ken McDonald, Liberal MP for Newfoundland’s Avalon riding, made clear the stakes of the federal decision last March, when speaking to the CBC about the project. “If this doesn’t go ahead,” he asked, “what does?”

Last April, Scott Penney was filling up his truck near the town of Deer Lake, in western Newfoundland, on his way to his daughter’s volleyball tournament, when a social media ping on his phone alerted him that Bay du Nord was approved. As Penney stepped inside to buy snacks and pay for his fuel, he heard the manager and another customer already talking about the news, moments after it dropped.

Penney is CEO of the Port of Argentia, on the western side of the Avalon Peninsula in eastern Newfoundland, home to about half of the province’s population and the city of St. John’s. The port is part of a vast network of businesses that will benefit from Bay du Nord—Penney expects at least 1,000 jobs in construction, fabrication, transport, docking, security and even local hotels, which often let out blocks of rooms to workers coming off weeks-long shifts. The port will be a transit and construction hub for the project. “As a Newfoundlander,” says Penney, “when you talk about the impact of these industries, and changing the generational outlook, you get almost blurry-eyed.”

Work on Bay du Nord hasn’t started yet; the province is still negotiating the project’s benefits agreement with Equinor, including parameters around how much manufacturing and construction will take place in Newfoundland. But the industry has begun to pick up again.

Amanda Young recently shelved her nursing school application—though she was accepted—when work started again on the Terra Nova platform. She’s optimistic now there will be work for years to come on Bay du Nord. So are most Newfoundlanders.

Bay du Nord’s opponents aren’t blind to this enthusiasm. They see it among friends and family, in their own communities. “There’s a patriotism wrapped up in oil and gas,” says Kerri Neil, co-chair of the Social Justice Co-operative of Newfoundland and Labrador, which has organized protests against the project. “There’s a perspective that if you don’t support it, then you don’t support Newfoundland.”

Robert Greenwood occupies a middle ground. He’d like to see oil revenues used to help transition the province to a new economic footing. “Our oil and gas is produced in an environment with safeguards for workers and environmental regulations,” he says. “Shouldn’t we continue to provide it? And use those crack-cocaine revenues to invest in hydrogen or wind power?”

This is roughly the perspective put forth in “The Big Reset,” a 2021 report commissioned by Newfoundland’s provincial government on the province’s economic future. “There are no short-term, realistic scenarios to replace petroleum royalty revenues necessary to provide public services,” it concluded. It advocated putting up to 50 per cent of oil revenues into a “future fund” to be used for debt repayment and the transition to a green economy. Last year, the province created a fund with that name, though it appears to be mostly intended to pay down debt. The legislation establishing it makes no mention of a green transition.

Today, the booms and busts of the past two decades are apparent everywhere in Newfoundland. Every time Kerri Neil drives from St. John’s to her home in Spaniard’s Bay, a small community about an hour out of the city, she sees the houses that started construction during boom years, later abandoned when their owners could no longer make mortgage payments. Newfoundland today has Canada’s second-highest consumer debt rate, and the third-highest debt delinquency rate.

There’s a cruel optimism surrounding any fossil-fuel project. Here’s one more chance for wealth—for a while. If the story of Bay du Nord is a patchwork of work and risk, it is threaded by the memory of loss. Young knows that the industry is not forever. But transitioning as quickly as Bay du Nord’s opponents hope, she feels, would be an impossible task. “We’d have to change our whole economy and how we think about living here.” For Curtis and Neil, that’s exactly the point.

Since Bay du Nord was approved, Scott Penney has noticed a change in his employees at the Port of Argentia. “There’s a pop in their step,” he says. “They know there’s work. A lot of times in the last number of years, there’s been this fear of when the shoe is going to drop.” Today, that question has an answer: not yet.

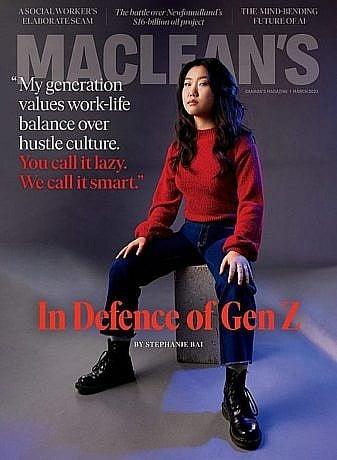

This article appears in print in the March 2023 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Buy the issue for $9.99 or better yet, subscribe to the monthly print magazine for just $39.99.