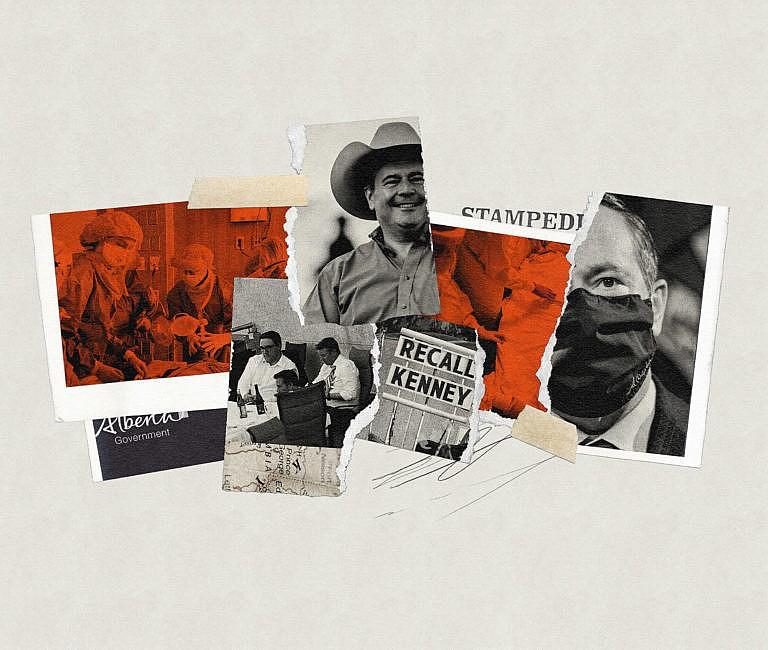

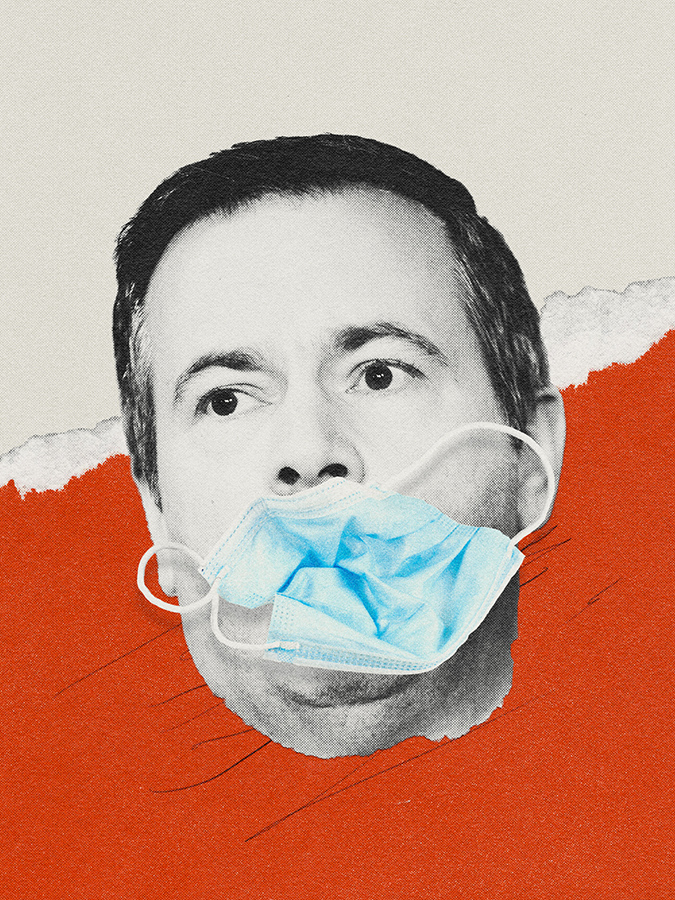

Jason Kenney is sinking. How it all went wrong for him.

The premier fumbled Alberta’s pandemic response so badly that his job is now in jeopardy

(Illustration by Ben Shmulevitch)

Share

Saturday morning at a rec centre parking lot in south Calgary. Flapjacks. Mediocre coffee. Disposable plates. Boots. Belt buckles. Cowboy hats of black, white and straw. Smiling kids. Glad-handing politicians. In some ways, it seemed like any traditional Calgary Stampede pancake breakfast, pleasing for a premier who’d declared a week earlier that Alberta was “open for summer.”

Traces of pandemic life still stood out that July day. Some people wore face masks, most of them food handlers. A clutch of protesters hollered against vaccines and public health rules, although the former were optional and the latter nearly nonexistent at the time. Security guards around the VIPs were plentiful, particularly for Jason Kenney and Tyler Shandro, Alberta’s health minister, on account of a demonstrator howling “war criminal” at them.

Then, a benign-seeming fellow got close enough for a one-on-one chat with Kenney. The premier, seeing the man’s phone out, offered to join him for a selfie, but the visitor demurred; he’d brought along his phone to surreptitiously get video footage of Kenney, which he’d later post to anti-vaccination social media.

RELATED: Will Jason Kenney sink the UCP experiment?: 338 Canada

The anonymous interviewer mentioned his anxiety about lockdowns, and began asking about the open-for-summer promise. “It’s open for good. Open for good,” Kenney insisted before the question was fully asked. Was he sure there was no going back? “I swear to God,” the premier said, making a cross symbol over his blue western shirt. “No. With the vaccines, we don’t have to.”

The man tried gently poking holes in the pledge—pressing Kenney about the risks posed by the unvaccinated, about the efficacy of the shots, about Australia’s return to lockdowns. The premier swatted the worries away with reassurances that COVID hospitalizations would remain flat like Britain’s, that Alberta’s population would soon be 80 per cent immunized, that unprotected young people posed no problem. “Don’t worry about it,” he kept saying.

In that two-minute exchange, nearly everything Alberta’s premier said was false, or would later be proven wrong. He misstated Australia’s vaccination coverage (32 per cent at the time, not 15); and he wrongly asserted that U.K. hospitalizations had stayed flat despite soaring cases (they’d tripled in one month) and that COVID had killed only two Albertans under 30 (the number was 11). He was wrong about bigger things, too. In July, Alberta was still two months away from having 80 per cent of eligible people with a single vaccine dose, and miles from that mark for coverage of the whole population. Spiking infection rates would send hundreds to hospitals, and his pledge that the province was “open for good” didn’t even survive the summer. In mid-September, Kenney reluctantly—and belatedly—reintroduced COVID restrictions and vaccine requirements.

The stunning wrongness of his pandemic approach worsened a brutal fourth wave and triggered a health-care catastrophe, while uncorking political anger that had been building since before the pandemic. By disappointing people on both sides of this polarizing issue, Kenney has infuriated not only those who never voted for him, but also the deeply conservative Albertans who voted for the idea of a supercharged right-wing leader.

It’s crippled Kenney’s leadership of the United Conservative Party, where quiet internal grumbles about the premier’s high-handedness have devolved into open hostility and demands—not least from his own MLAs—for his resignation. Barring a miraculous turnaround, his days as premier appear numbered. Even his loyalists say so. And his political demise, later this year or early next, would mark a stunning reversal of fortune. Only two years ago, voters had embraced Kenney as a political colossus who’d make Alberta muscular again. He’d swooped westward from Ottawa, where he had dazzled with his smarts, steadfastness, tactical cunning and communications savvy. Those talents have now either abandoned him or proven to be overblown, while his calamitous mistakes have taken a toll—on his reputation, his party and his province. It’s a downfall story whose operatic scale is eclipsed only by the gravity of its real-world consequences, measured in human suffering and lives lost. How did one of Canada’s most successful politicians—a conservative star whose entire career seemed to lead him to a top job—fail so badly, just when Alberta needed him most?

Watching him up close, Corey Hogan came to question the idea of Jason Kenney as a master strategist, a reputation developed through years in federal politics as Stephen Harper’s cabinet minister and political rainmaker. Former NDP premier Rachel Notley had hired Hogan, a veteran politico, to lead the Alberta government’s communications office, and he stayed on for a year under Kenney. Hogan now reckons that Kenney is a great in-the-moment tactician, someone who can win the day but might set himself up for rough days ahead. “He’s clever, but sometimes you wonder: can he see the whole board, and where the next couple of moves are?” Hogan tells Maclean’s.

Kenney cut his political teeth as an MP for the Canadian Alliance and then the Conservatives, thriving in the parties’ election war rooms, where rapid response and quick point-scoring were the orders of the day. He was a savvy message deliveryman, and still enjoys slapping down critics, real and imagined. In late July, when asked about warnings that the Delta variant threatened Alberta, he snapped: “I think it’s time for media to stop promoting fear when it comes to COVID-19, and to start actually looking at where we’re at with huge vaccine protection.” (His aides promptly made a Facebook meme of it.)

When he first rode into Alberta in his blue pickup truck, Kenney seemed a canny long-term thinker, perfectly executing a complex plan to take the reins of the province. Within three years, he won leadership of the once-invincible Alberta Progressive Conservatives, merged them with the right-wing Wildrose Party, became leader of the United Conservatives and easily ousted the NDP in the April 2019 election. He did it all with a mix of cheery populism and screw-our-enemies combativeness, but governing has proven far trickier. Among other things, the man who won by promising to fight “unapologetically” for Albertans has had to issue three apologies to them in 2021, all for COVID-related debacles.

The first came in January, when several of his MLAs, a cabinet minister and his chief of staff were caught during the second wave travelling abroad amid near-lockdown conditions. He claimed he was unaware of their travel plans, but apologized for what he called “bad decisions.” Then, in June, during another wave and another round of restrictions, photos circulated of Kenney enjoying wine and Irish whisky with ministers and aides on the patio of a penthouse government office nicknamed the “Sky Palace.” “It is clear that some of us were not distanced the whole night, and I have to take responsibility for that,” he said.

RELATED: What Jason Kenney’s ‘mission accomplished’ moment has reaped for Alberta

Finally, in September, with the fourth wave raging, the premier confessed he’d been overly optimistic in thinking Alberta was moving on from the pandemic.

Before each mea culpa, Kenney spent days—or weeks—either justifying his actions or avoiding comment. Frustrations would simmer, not just among critics and partisan opponents, but among UCPers who sneer at waffling and excuse-making. Finally, when the pressure became overwhelming, the rage kettle sounding its deafening whistle, he would stop digging in.

The first two incidents were flashes of dreadful optics, but didn’t have the grave real-world consequences of the judgment lapse for which Kenney answered on Sept. 15. His government had proudly promoted its maskless, distancing-free “open” summer, encouraging mass gatherings like a full Calgary Stampede. It even sold “Best summer ever” ballcaps to raise funds for the UCP. The messaging carried all the bravado and certitude of the “Mission Accomplished” banner George W. Bush posed before in 2003, after the U.S. military deposed Saddam Hussein in Iraq, only to see warfare drag on for another eight years.

The reopening led to a resurgence of the virus in late July, and Kenney’s government allowed hospitalizations to rise rapidly throughout August before reintroducing an indoor mask mandate. By the afternoon of his apology—the same day the province announced a vaccine passport system—Alberta ICUs contained 10 times as many COVID patients as they had in early August. Hospitals double-bunked patients and expanded into overflow rooms. The military and the Red Cross brought in staff reinforcements. To keep the critical-care units from completely overloading, hospitals cancelled thousands of surgeries, including those for children and cancer patients. Daily COVID fatalities reached heights not seen since last winter, when unvaccinated residents of seniors homes fell victim to the virus.

READ: Jason Kenney’s days may be numbered. Erin O’Toole’s too.

Surprisingly, none of this fell within the scope of Kenney’s narrow apology. He voiced regret for his government announcing plans to abandon mass coronavirus testing and rules requiring the infected to isolate—an audacious leap beyond the “open for summer” mask-burning bacchanalia, and one the government was forced to rescind. But he pointedly refused to apologize for relaxing health restrictions, arguing the move was supported by data on dropping case rates and vaccinations, and by the experiences of other countries.

These assumptions, as Kenney hinted to his lecturee at the pancake breakfast, leaned heavily on the “de-coupling” of hospitalizations from rising case rates in Britain. This, reflects one source close to Kenney, was “the wishful thinking of a government that was desperate” to return to normal. The growth of the U.K.’s severe COVID cases did slow somewhat, thanks to vaccination, but it was a “major folly” to overlook the distinctions between the jurisdictions, says Dr. Ilan Schwartz, an infectious disease specialist and University of Alberta professor of medicine.

Among them: vaccine coverage was spread relatively evenly throughout the U.K., whereas when Alberta hit the 70 per cent mark for first doses among eligible residents, coverage outside Calgary and Edmonton lagged badly, in some communities well below 50 per cent. In a pattern similar to the nightmarish experience in parts of the United States, smaller regional hospitals were overwhelmed first, then those in big cities. “It was cherry-picking data from one experience that matched the fantasy of what they had hoped to achieve,” Schwartz says. Kenney’s protective measures, he adds, came far too late to prevent catastrophe in the ICUs.

MORE: Jason Kenney in conversation with Paul Wells: Maclean’s live replay

Even Dr. Deena Hinshaw, the provincial government’s top public health doctor, who rarely contradicts Kenney, would later concede the fourth wave “trajectory was set when we removed all the public health restrictions at the beginning of July.” Provinces that exercised greater caution avoided significant impact, she noted during a video meeting of Alberta physicians.

Alberta’s COVID death count has now surpassed 3,000—with more families losing people to the virus in the 30-day span ending Oct. 20 than in Ontario, Quebec and hard-hit Saskatchewan combined, while its case rate—7,186 per 100,000 residents—is the worst in the country. But caution hasn’t been Kenney’s primary impulse. Not in the second wave, or the third, or the fourth.

All of this has made Kenney a politician scorned on both sides of the coalition he’d forged between his red-meat conservative base and Alberta’s increasingly moderate Tory centre. His long periods of pushback against public-health measures—and, more recently, against vaccine passports—have defied the wishes of a majority of Albertans, who’ve repeatedly told pollsters they prefer stronger pandemic restrictions. In a September Léger survey, 77 per cent said they supported proof-of-vaccination rules; only 23 per cent opposed them.

But an outsized share of the “anti” segment appears to reside within the rural grassroots and caucus of Kenney’s party. In April, amid the throes of the third wave, an open letter from 16 rural and small-town UCP MLAs decried the premier’s reluctant move to close indoor dining and gyms. The backbenchers said they’d rather defend “livelihoods and freedoms.” Sources say Kenney struggled in September to persuade his MLAs to reintroduce mandatory mask usage, and one publicly acknowledged that the caucus softened Hinshaw’s vaccine passport proposal. The final version allowed individuals to forgo the jab in favour of testing, while businesses could accept new capacity limits instead of checking for vaccination proof.

READ: Jyoti Gondek and Amarjeet Sohi: A joint interview with Alberta’s new progressive mayors

At the same time, though, anxious Albertans who demanded action grew exasperated with Kenney’s pattern of stalling, shrugging and taking steps when the damage was already done. In Hogan’s mind, the premier has been “trying to ride both horses with one ass, and he’s got the bruises to show for it.” Now, he says, Kenney has “a situation where there are long memories on the right, and long memories on the left and centre-right.”

Samantha Steinke, an early Kenney supporter who was initially impressed with her leader’s tough talk and anti-Ottawa posturing, has had it with his policy yo-yoing. “If we could have said, ‘This is what we’re doing, this is the lane we’re staying in,’ I think people could have respected that a little bit more,” she says. Steinke is a northern Alberta UCP constituency association president living in Valleyview, where nearly 40 per cent of eligible residents were still unvaccinated in October. The MLA for her riding, Todd Loewen, got turfed from caucus in May for calling for Kenney’s resignation. Steinke has since been working to persuade fellow UCP constituency boards to support a prompt leadership review.

Those efforts gained steam this fall. Joel Mullan, the party’s vice-president of policy, publicly demanded that Kenney quit, saying he felt betrayed by the vaccine passport that Kenney had sworn he wouldn’t impose. “If he says something now, the question is: is this going to apply in a couple of months?” Mullan says in an interview. (In the end, Mullan’s fellow UCP executives voted to purge him, instead.)

Urban moderates in caucus, meanwhile, seem just as willing to denounce Kenney. Calgary-area MLA Leela Aheer was bounced from cabinet after publicly criticizing the premier’s penthouse patio gathering that defied restrictions he’d imposed. In September, she told the Calgary Herald: “We need to heal our province right now, and that requires people who have failed in their leadership to step down and admit their mistakes.” Richard Gotfried, who represents a suburban Calgary seat next to Kenney’s, stated on Facebook that the government’s lack of responsiveness “will cost us lives.” His riding association also wants a fast-tracked leadership review.

The two wings of his party and caucus agree on little, then, except that Kenney has mismanaged things and become a liability to UCP political fortunes. The premier’s unpopularity is widely believed to have eroded the Conservative vote in Alberta during the recent federal election, where three seats flipped to the Liberals or NDP. One day after the vote, Kenney replaced Shandro (sources tell Maclean’s the health minister had threatened a few times to quit). The day after that, a rural UCP backbencher went into caucus with a motion of non-confidence in Kenney’s leadership that the premier’s critics assumed had dozens of supporters.

That effort fizzled, but behind closed doors Kenney agreed to face a leadership review in the spring of 2022 rather than next fall as scheduled. Crucially, though, his backers secured an open vote instead of a secret ballot, which will make it dicey for ministers to publicly knife him, lest he survive and punish them.

MORE: The lonely life of a wildfire lookout in northern Alberta

So the tactician won the day, buying himself time. Still, it’s hard to see Kenney’s plan from here—to discern whether it’s a survival strategy or an exit ramp. The source close to the premier figures the party is more likely to tolerate him for the rest of the year if members don’t think he’ll be leading them in the next election, in 2023.

It’s an astonishing collapse for a politician whose party netted 55 per cent of votes just 2½ years ago, the biggest share since Ralph Klein’s election in 2001. But Conservative politics in Alberta has seen a high churn rate in the last two decades: Klein stepped down early after winning in 2004; Ed Stelmach after 2008; Alison Redford, amid scandal, after 2012.

Polls suggest the New Democrats are on track to win their second-ever mandate in 2023, while fundraising records show they grossed twice as much as the UCP in the first half of 2021, obliterating Kenney’s past advantage. A ThinkHQ poll published in October pegged the premier’s approval rating at just 22 per cent, suggesting he’s deeply unpopular in both urban and rural Alberta—even among UCP voters.

The pandemic has been the primary source of Kenney’s political unravelling, but there’s more behind his fall. With a workaholic’s determination to enact every last promise in his exhaustive 375-pledge election platform—pandemic be damned—Kenney has pressed forward on files that have expanded opposition beyond NDPers. There’s a radical, memorization-heavy overhaul of the education curriculum that almost all school boards have refused to test; a nasty protracted pay dispute with doctors that aggravated rural physician shortages; and a bid to open Alberta’s southern foothills to more coal mining, which upset everyone from farmers to small-town mayors to country music stars.

“He was always very critical of Harper for being an incrementalist, that we weren’t moving quickly enough,” says a former Conservative official who respects Kenney. “This is why [we weren’t].” If Harper tried to move this fast, and burned that much political capital, the official says, he’d have been a one-term prime minister.

Now, to say the least, managing the loosely stitched alliance of former PCs and Wildrosers in his caucus promises to be a struggle. Kenney had long idealized a more British model of tolerating heterogeneous views in caucus. But that’s not the model that worked for Harper, nor one that works in any Canadian jurisdiction. Angela Pitt is a UCP MLA and critic of public health restrictions who has publicly declared her loss of confidence in Kenney’s leadership. Of the government’s period of inaction in August while the premier vacationed in Europe, she tells Maclean’s: “Everyone had this sense we were this rudderless operation.”

Pitt, who’s been in Kenney’s caucus since 2017, continues: “To be honest, I don’t know the guy. I just know the public looks at him and says, ‘We don’t trust you.’ ” She complains that the leader who once said he was attuned to the party’s grassroots now barely listens to his caucus. “Those who sit around the white tablecloth are the ones that are running the government,” she says, in an acid reference to the penthouse patio gathering. Her words speak to a greater problem Kenney faces: rural conservatives worry he only pays attention to Calgary; Calgarians worry he’s in thrall to the rural base; and some believe he only listens to his own instincts.

READ: Trudeau’s new cabinet: Serious people in charge of serious files

To be sure, not everybody in the UCP has written him off. Evan Menzies, a former party communications director, acknowledges there are angry members “in every corner of the tent,” but says “there is a silent Jason Kenney loyalist faction of the party.” To mobilize and expand that support, says Menzies, “he’s got to start scoring some wins in the next few months.”

Any plan that saw Kenney past an April leadership review—or sooner, if detractors have their way—would rely on several ifs. If he can steer through the fourth wave without deeper human tragedy. If he can notch policy victories for his base that don’t alienate the broader public. If he can unify his rancorous caucus. If Alberta’s long-struggling resource-based economy can take off again, leveraging higher oil prices that have yet to translate into jobs.

For now, Kenney is down to trying to woo back his base in Facebook Live townhalls—recurring Premier-Explains-the-World events where he responds to audience questions as expansively and wonkishly as he sees fit. In mid-October, as the province finally passed its peak of new COVID cases and hospitalizations, he sat alone in an armchair in an office one level below that penthouse patio—a gas fireplace and blue curtain behind him, a framed photo of Alberta’s legislature dome at his left shoulder.

With a camera trained on him, temples gently glowing under the lights, he fielded a query about when mandatory masks and other public health impositions would end. Perhaps having learned a lesson about risk, he began by counselling caution: “We don’t have specific metrics, to be blunt. Our immediate focus is simply getting this fourth wave under control.” But his response then went on for six minutes, replete with myriad stats, a New York Times article citation, a prediction the vaccine passport system that some colleagues deplore will continue well into 2022 and an expression of hope (“please God”) that the pandemic will finally be behind us six months from now.

As he spoke, torrents of Facebook comments streamed alongside his window: scorn from those who believe Kenney jeoparized Albertans’ health, fury from those who believe he stole their freedom. Sure, that was on social media, where everyone hates everything. But time was, a good many fervent partisans and believers in Jason Kenney would’ve weighed in, too, cheering on the premier who landed in Alberta as their hero. Not anymore.

This article appears in print in the December 2021 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “The incredible sinking man.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.