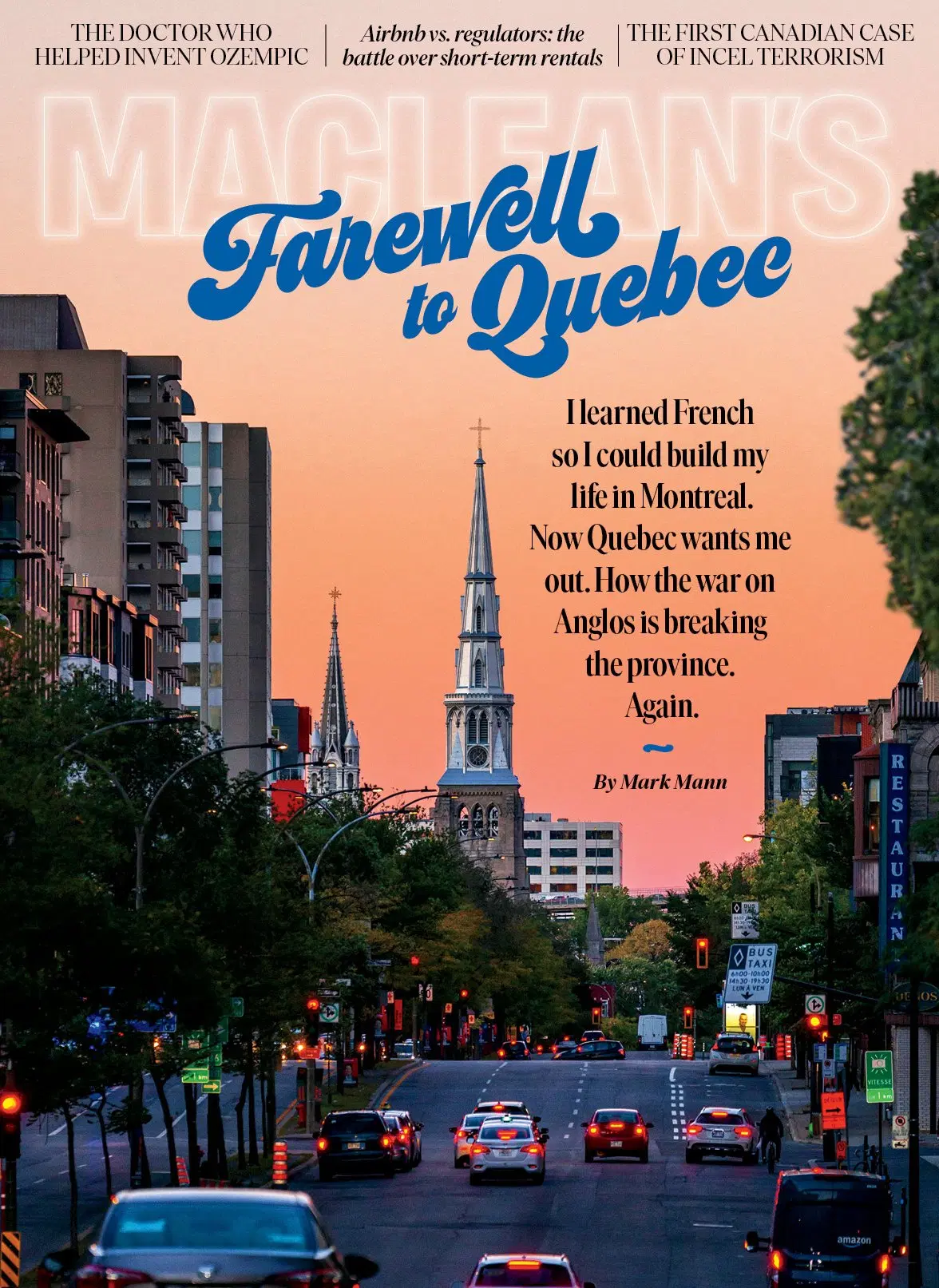

Quebec’s New French Revolution

When I moved to Montreal, it was a vibrant, multilingual metropolis. Now François Legault is waging war on English and on the cosmopolitanism that makes it Canada’s greatest city.

Share

March 19, 2024

When François Legault is in downtown Montreal, he doesn’t like what he hears. Quebec’s premier works from an office on Sherbrooke Street, right in the heart of the city, only a few blocks from the mountain that gives Montreal its name and directly across the street from the Roddick Gates, the grand, columned entrance to McGill, Quebec’s most prestigious university. And it is the sound of English, not French, that often dominates here. To the northeast is Milton Park, a neighbourhood packed with McGill students. To the west is Concordia, the province’s biggest English university. The immediate area is known as the Golden Square Mile, once a bastion of the city’s anglophone elite. At times, you might forget that you’re in the middle of North America’s only French-speaking metropolis. But last October, Legault’s government announced a new policy, one with the potential to transform the troublesome linguistic landscape near his workplace—and one that landed like a bomb in the world of higher education.

It was a two-parter. First, the Quebec government announced it will stop subsidizing tuition for out-of-province students. Every provincial government in Canada provides these subsidies for Canadian students, regardless of their province of origin. Quebec’s radical plan was to make out-of-province students pay for the entire cost of their education. That would mean roughly doubling their average tuition from about $9,000 per year to $17,000. The second part of the plan received less press, but was perhaps even more dramatic: the government said it will set a minimum fee of $20,000 for international students, then claw back $17,000 to redirect to francophone universities. The policy didn’t name the English schools directly, but McGill and Concordia were the obvious targets. Combined, the schools attract by far the most out-of-province students, the majority of whom are anglophones.

The only thing more stunning than the particulars of the plan was its abruptness. The policy would apply to next year’s incoming class, but university presidents received almost no advance notice. Recruitment, already well under way, was thrown into turmoil. High school students from other provinces considering a degree in Quebec couldn’t tell how it would shake out, and the universities didn’t know what to say to them. “It was chaos,” Graham Carr, Concordia’s president, told me in January, in his bright, eighth-floor office on Maisonneuve Avenue. “What’s the message you’re supposed to be giving to your students? You don’t know.”

Carr predicted at least a 65 per cent drop in out-of-province admissions and an $8-million revenue loss in the first year. McGill announced it could face, in the worst-case scenario, up to $94 million in losses annually and anticipated cutting up to 700 jobs. The Montreal Chamber of Commerce warned that out-of-province students’ economic contributions to the city, totalling more than half a billion dollars per year, was in danger. In November, the credit-rating agency Moody’s placed both universities under review for a credit downgrade, though didn’t go through with it in the end. A deepening mood of mystification and horror suffused the opinion pages of the Gazette, Montreal’s English newspaper, while the city’s mayor, Valérie Plante, called the plan a threat to Montreal’s global reputation. She also said it would send prospective students to Toronto universities instead—which, reading between the lines of Legault’s comments, might have been exactly the point. In a private meeting with university leaders at McGill and Concordia, he said that with 80,000 students between them, the schools were just too big compared to their French counterparts. He also told reporters, “When I look at the number of anglophone students in Quebec, it threatens the survival of French.”

Two weeks after the announcement, thousands of students from McGill, Concordia and Bishop’s, a smaller Anglo school in Sherbrooke, gathered to protest outside Legault’s office—producing a cacophony of English, to be sure. Their dismay and disbelief were summed up by one sign visible during the march: “I love Quebec, but it doesn’t love me.” For the students, and for English speakers in Montreal at large, the tuition policy seemed like a brazen attack. It came on the heels of a new language charter the government passed in 2022—an update to Bill 101, possibly the most contested piece of legislation in Quebec history, which in 1977 entrenched French as the lingua franca of Quebec. The charter sparked decades of legal challenges over allegations that it had curtailed the rights of anglophones.

The government did bend on the tuition policy, a little bit. In December, Minister of Higher Education Pascale Déry announced tuition would rise to only $12,000, instead of $17,000. But she also announced that 80 per cent of out-of-province and international students would have to reach an intermediate level of French proficiency by graduation. Universities that didn’t achieve the target would be fined. In some ways the revised policy was worse: a still unworkably steep tuition spike coupled with a punishing francization policy that would be impossible to meet and would especially deter international students. “I don’t think there’s even a discussion of how to make it possible,” Fabrice Labeau, McGill’s deputy provost, told me. (Bishop’s was given a substantial exemption; it will still need to meet the francization requirements, but tuition will not go up. Many observers feel it was collateral damage in the first place, from a plan mostly targeted at McGill and Concordia.)

As shocking as the policy was, it seemed grimly predictable in retrospect. If Canadians were surprised by the tuition hikes, that’s only because, for many, it was the first time Quebec’s new language war had reached across provincial borders and tapped them on the shoulder. The message they hear is: “Stay away. We don’t want you here.” For years, politicians and parts of the pundit class in Quebec have peddled the idea that French is in decline, and Quebec is just a few steps away from being a northern Louisiana—a once proudly French society, anglicized out of existence. Montreal’s universities, drawing thousands of Anglos to the heart of the city, have been scapegoated as the rich, privileged villains in the decline. This view is especially prevalent in the francophone regions outside the city that form the electoral heartland of Legault’s governing party, the Coalition Avenir Quebec, or CAQ. There, complaints about budget difficulties from the president of McGill are met with shrugs. “Nobody outside of Montreal gives a shit,” one francophone friend told me, confirming a sentiment I’ve heard over and over.

Framing the government’s language war in militaristic terms isn’t hyperbole, either. Legault’s government constantly invokes the vocabulary of battle; the day before the tuition announcement, Quebec’s minister of the French language, Jean-François Roberge, outlined an upcoming 50-point action plan to protect French. “It’s time to regain some ground,” he said. As far back as 2017, a year before he became premier, Legault told a group of young CAQ supporters it was time to push for a new Quiet Revolution—hearkening to the seismic shifts in Quebec society, beginning in the ‘60s, that renewed the centrality of the French language and ended the domination of a small Anglo elite. In the years since, Legault has often invoked that era, and presented himself as a leader who can finish the job of reclaiming Montreal for francophones. In doing so, he’s pitting anglophones against francophones, Montreal against Quebec, and Quebec against the rest of Canada.

Since I was a kid, I knew I would live in Quebec. Maybe the seed was planted when I started Grade 1 in French immersion in 1988 and learned that “airplane” in French is “avion”—a fact I found fascinating and memorable as a six-year-old. Today I live under a flight path in Montreal’s Villeray neighbourhood, where every day I hear planes overhead and think, avion.

Though I didn’t visit Quebec as a child and can’t even remember meeting a francophone—they weren’t common in rural Prince Edward Island, where I was born, or West Virginia, where I spent my teenage years—I somehow became a committed francophile. In 2002, when I was 18, I moved to Paris for eight months to work as a nanny and take French classes (which I passed by the skin of my teeth). The following summer, I joined a French-language intensive at the Université Sainte-Anne, in the Acadian village of Pointe-de-l’Église, Nova Scotia, where I watched my first Denis Villeneuve movie, Maelström, and lost my virginity. At summer’s end, my mother drove me from Halifax to Montreal and dropped me off at a rundown townhouse near Concordia, where I lived while I studied at the university’s Liberal Arts College. The LAC is one of those small, charming programs where people who don’t know what they want to be when they grow up can read Beowulf and Boccaccio while they sort it out. It also claims the highest percentage of out-of-province students of all the programs in Concordia’s arts and sciences department.

The Montreal that I discovered in the early 2000s was an exhilarating, multilingual city. My first housemates were from Toulouse, France, and all were studying at Montreal’s French universities. None spoke English. My friends from Quebec possessed an easy, enviable bilingualism, switching fluidly between languages. The entire city felt so confidently bilingual that I could hardly imagine linguistic tensions. Admittedly, I mostly stayed inside an English bubble, as many students do. Still, my admiration for bilingualism was so ingrained it didn’t occur to me that most Quebecers conceive of the province as a unilingual, francophone nation. And that for many of them, the multilingual hodgepodge of Montreal is a problem, or even an affront.

I also didn’t understand the degree to which Quebec society had been reforged around the French language long before I arrived, starting with the Quiet Revolution. Before that, an anglophone elite ruled commerce, politics and culture. In Montreal, especially, English was “the language of money,” as the Quebec poet and politician Gérald Godin described it. Montreal was Canada’s largest urban area—Greater Toronto didn’t edge into first place until 1976—and its economic nucleus. The city became central to the efforts to remake Quebec society. The nationalist organization La Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste sought nothing less than to reclaim the city from the English, even running a campaign in the mid-1960s called Opération Visage Français, to make Montreal “the natural metropolis of French Canadians.” The English universities—among the city’s premier institutions—would have to be French too. In March of 1969, more than 10,000 people marched down Sherbrooke Street to McGill’s gates, crying “McGill aux Québécois!” and demanding the school become French. English students on the other side of the gate responded by singing “God Save the Queen.”

McGill didn’t become French, of course, but the period gave rise to an exciting, ambitious nation-building movement. Private energy companies were nationalized, and Hydro-Québec electrified the province’s way to economic freedom—though this legacy came at the price of flooding thousands of square kilometres of Indigenous lands in northern Quebec for hydro reservoirs. The Catholic Church’s power was diminished, and language came to fill the void religion left. French itself was the new vehicle that would drive Quebec onto the world stage as a rich, confident, outward-looking nation.

Of course, to do so, a few eggs would have to be broken. In 1977, the government passed Bill 101, the Charter of the French Language. It cemented French as the language of government, work and school. In response, it sparked one of the largest internal migrations in Canadian history. Over the following 20 years, more than 300,000 English speakers left the province. Many who remained were locked in a constant battle to preserve their own linguistic rights. Mordecai Richler crystallized this sense of Anglo embitterment in his book Oh Canada! Oh Quebec!, which mocked the bureaucratic juggernaut that had been created to implement language laws.

It was into this world that François Legault came of age. Born in 1957, he was raised in a francophone family in the primarily anglophone enclave of Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, on Montreal’s West Island. His childhood and adolescence put him on the frontlines of the Quiet Revolution; even teenage hockey matches were divided by language. As a teenager, he and his friends grew tired of seeing the businessmen reading the English-language Gazette on the train, so he convinced the newsagent to carry Le Jour, a separatist newspaper. “We took great pleasure in opening it up in front of those surprised businessmen,” he has said.

He finished his training as an accountant in 1978, one year after the passage of Bill 101. In this new era, the future premier never needed to master English to attain the highest peaks of success. He started at Ernst & Young at age 21, joined the airline industry at 28 and co-founded Air Transat the following year, in 1986. In 1997, just shy of his 40th birthday, he was a rich man. A sovereigntist, he joined politics the following year as an appointee by Parti Québécois premier Lucien Bouchard to head the Ministry of Industry, Commerce, Science and Technology. He was elected that year to the national assembly for the first time, in the riding of Rousseau, just outside of Montreal. Bouchard said that he represented “the economic ambition of Quebec.” As I was polishing my second-year thesis at Concordia, Legault was putting the final touches on his landmark budget for an independent Quebec, published in 2005. “Not only is the sovereignty project relevant today, it has become urgent,” he said when presenting it.

In 2006, I finished my studies at Concordia and left Quebec. My French was good enough to work service jobs, but I didn’t see much career potential as an anglophone journalist in the province. So I moved to Ontario for the next 10 years. I started to think I’d dodged a bullet by leaving; many of my anglophone friends who stayed in Montreal struggled to find good jobs. In fact, anglophones in Quebec today have a far higher unemployment rate than francophones and greater levels of poverty, a partial reversal of the inequality that prevailed before the Quiet Revolution.

The year I left, a right-wing populist party called the Action démocratique du Québec, or ADQ, experienced a surge in support among the de souche majority—those who could trace their ancestry to the province’s earliest French colonial settlers. The ADQ marshalled a sense of resentment in this group over so-called special treatment for those who don’t share a white, Christian, European heritage. In 2007, the ADQ won 41 seats in the provincial election, not far behind the winning Liberals’ 48, and became the chief opposition to the government.

Two years later, Legault left politics, dismayed by what he saw as inter-party squabbling between the Liberals and the PQ. But he came back in 2011 with a solution: a new, centre-right party called the Coalition for the Future of Quebec, later called the Coalition Avenir Québec or CAQ. It was not a sovereigntist party. Instead, it aimed to unite federalists and separatists and to move beyond the political impasses the province had been mired in since the last referendum on independence, in 1995.

Months after the CAQ was founded, it merged with the flagging ADQ, bringing under its wing that party’s conservative, culture-war bona fides. Right from the beginning, the new party made the idea of French in peril a core tenet of its brand. That simplistic messaging exploited many people’s longstanding fears, but the reality is that French was thriving. The Quiet Revolution really had succeeded in flipping the linguistic polarity. In Montreal, especially, a truce seemed to have been brokered, allowing French and English—and a wealth of other languages—to live side by side with relative ease. But to listen to Legault, you would be forgiven for thinking nothing had changed since his boyhood days scrapping with English kids on the streets of Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue.

With its clear message and a big tent, the CAQ became, as political sociologist Daniel Beland described it to me, a “machine to win elections.” At the top of its priority list? Relitigating the language fight that many Quebecers, and especially Montrealers, hoped was in the past.

In 2016, I returned to Montreal on a story assignment and went on a date with a professor at Dawson College, an English CEGEP. Like me, she was an out-of-province anglophone who had studied at Concordia. Two months later, I rented an apartment in the city and, two years after that, we got married at a second-floor dance studio on St. Laurent Street. I was back for good. Three months later, Legault led his CAQ to a majority government, with 74 of 125 seats. The election produced one of the starkest urban-rural electoral divides in Canada: the CAQ swept the regions, while the city went hard for the Liberals and Québec Solidaire, a left-wing sovereigntist party. The CAQ won only two seats on the island of Montreal.

It soon became clear that voters who’d chosen the CAQ over the PQ might have been compromising on sovereignty, but they didn’t intend to compromise on language, nor on a vision of Quebec society in which the cosmopolitanism of Montreal seemed insidious and threatening. That became overwhelmingly apparent in 2019, when the government passed Bill 21, which banned public employees from wearing religious symbols, including hijabs, yarmulkes, turbans and crosses. It was passed, supporters say, in the spirit of protecting Quebec secularism—a key principle of the Quiet Revolution that helped the province emerge from under the boot heel of the Catholic Church. To its opponents, though, Bill 21 was nothing less than a violation of human rights, excluding people from participating in certain jobs and parts of public life based on religious belief. The law passed on June 16, 2019, when my son was six weeks old. I was discomfitingly conscious that I was inducting him into a world of white privilege in Quebec—one in which he was automatically immune from punitive laws targeting racialized minorities.

Not all francophones were in favour of Bill 21, of course. To some younger people especially, Legault looked like a classic mon’oncle: an aging, conservative man with an angry, regressive outlook. But to his admirers, he’d imbued the CAQ with an air of bold action. When the pandemic struck in 2020, his plainspoken persona propelled him to another peak of popularity, with a 77 per cent approval that spring. I remember listening to him around that time and being impressed by the folksy polish of his delivery, like whisky and fries.

It was with that soaring approval rating that his government introduced, in May of 2021, its next volley: Bill 96, an update to the original language charter, which deepened and expanded its reach, relying mostly on simplistic claims about the decline of French. The bill was crafted based on the findings of Canada’s 2016 census, which had, in fact, marked a slight decline in French use in Quebec. Then the 2021 census data came out—and it hit the language debate like a shot of nuclear fission. It showed that mother-tongue francophones in Quebec had declined from 81 per cent of the population in 2001 to 75 per cent in 2021, a fact that stoked sheer panic in some circles. It also revealed that of immigrants admitted between 2016 and 2021, 65 per cent spoke French at home compared to 74 per cent of those admitted in the previous five-year period. The revelations set off a wave of dire prophecies.

In the spring of 2022, Bill 96 passed. It required government employees to speak and write exclusively in French, with some exceptions for health-care employees (though anecdotes about non-francophone patients being denied care have circulated frequently in the media). It gave immigrants only a brief six-month window after arriving to learn French before being forced to use the language when engaging with all public services. Small businesses were no longer exempt from certain stipulations of Bill 101 and would be forced to do things like draw up contracts in French and make French websites. They would also have to report how many of their employees couldn’t speak French, data to be included on a public registry. It capped the number of students who could enter English-language CEGEPs and required all graduating students to pass a notoriously difficult French exit exam.

Resistance mounted fast. By last summer, there were multiple suits against the government over the new law. One is led by a group called the Task Force on Linguistic Policy, which declared, “The government of Quebec has created and promoted a social climate where the use of the English language is restricted and disdained.” The group has, so far unsuccessfully, requested Quebec’s Superior Court to issue an injunction on any new language laws until suits against Bill 96 are settled. The task force’s suit represents multiple plaintiffs who claim to be victims of discrimination, unable to access services, including medical services, in a language they understand. One is a woman from Central America who can’t get health care in English for her ulcerative colitis. Another is the parent of an autistic child who can’t access supports in English. Other plaintiffs in the case talk about threatening work environments, where failure to speak French is cause for dismissal.

The leader of the group is Andrew Caddell, a fast-talking former broadcast journalist, fluent French speaker and self-described francophile, who says he wants to disrupt preconceptions about embittered “angryphones.” He says he’s the only anglophone in the small town where he lives, east of Quebec City, where he holds a seat on the council. He feels his complete integration into francophone society puts him in a special position to advocate for anglophones.

He also says—and he is not alone—that the entire premise of Bill 96, and the government’s new language wars, rest on extremely shaky ground. The government’s catastrophic doom and gloom about French decline is focused on two things: mother-tongue francophones are declining, and fewer people speak French at home. But if you look at the language spoken in public, at work, in the wider world, the picture changes dramatically—and the victories of the Quiet Revolution, and the original Bill 101, become undeniable.

Jean-Pierre Corbeil is a sociologist at Université Laval and part of an emerging academic movement pushing back against the narrative of French decline. “By focusing on the results of the 2021 census, almost 40 years of significant progress in the development of the presence and use of French as a common public language have been eliminated from the discourse,” he writes in his new book, Le français en déclin?, which challenges the CAQ’s pessimistic messaging.

In fact, he argues the opposite. Bill 101 pushed many anglophones out of the province. Those who stayed, however, became more bilingual. In the past half-century, the proportion of anglophones who speak and read French has nearly doubled, from 35 to 72 per cent. Nearly 95 per cent of all people in Quebec claim to speak French, as of the last census. Another common cause of anxiety among French-decline alarmists is that only 48 per cent of people on the island of Montreal speak French—but again, that refers to people who exclusively speak French at home. It ignores the 332,000 multilingual Montrealers who speak French along with other languages at home. And it also disregards the fact that 81 per cent of immigrants are able to carry on a conversation in French. In 1971, only 53 per cent could.

The fact is, French is not in decline. It is more than ever the common language of Quebec, and of Montreal. The only thing in decline, slightly, is unilingual francophones. And this in itself may be part of what irks the CAQ and many of its supporters. On the 2022 campaign trail, Legault decried the very idea of multiculturalism, saying it was important to have “one culture, the Quebec culture.” His immigration minister, Jean Boulet, called into question immigrants’ compatibility with Quebec culture. “Eighty per cent of immigrants go to Montreal, don’t work, don’t speak French and don’t adhere to the values of Quebec,” he said.

Whatever Montrealers felt, Bill 96—and the CAQ’s hardline rhetoric about protecting Quebec culture—were roaringly popular beyond city limits. The bill’s passage propelled the CAQ to even greater gains in the election in the fall of 2022, when it won even more decisively than in 2018, with 90 seats—though it was again almost entirely shut out of Montreal.

But by the fall of 2023, a series of gaffes and reversals—including cancelling an expensive tunnel project beneath the St. Lawrence River, between Quebec City and the suburb of Lévis—had robbed the government of its shine. Polls in September of 2023 revealed Legault’s support was plummeting. That same month, in a by-election, he lost an important seat in Quebec City to the Parti Québécois. It’s probably no coincidence that, just weeks after that upset, Legault made his boldest move yet in the new language wars.

The tuition hikes shocked most of Canada, but anyone paying close attention to the political conversations unfolding in the province could have foreseen that something was coming. Martin Maltais, a professor at the Université du Québec who specializes in education financing and served as deputy chief of staff to former higher education minister Jean-François Roberge, has been especially strident in his attacks on English universities. Early in 2023, he published a series of articles in Le Journal de Montreal criticizing the exorbitant subsidies Anglo students have long enjoyed. Of course, all domestic students in Quebec and across Canada claim public subsidies, since the cost of tuition doesn’t come close to paying for their studies. But it’s true that a small portion of out-of-province students have long enjoyed an amazing deal in Quebec. Prior to the new policy, an arts or science degree at McGill or Concordia would cost them roughly as much as they’d pay elsewhere in Canada. Degrees in some programs, however, including law, medicine and engineering, were much, much cheaper. (Even with the new tuition hikes, some of these will still be cheaper in Quebec.) Maltais’s solution was for the province to cut off the Anglo universities entirely, and let them sink or swim as private entities.

The laureled economist Pierre Fortin has also written about “rich anglophone universities,” and the advantage they have over French universities when attracting international students. Again, that’s a fair critique. Unlike elsewhere in Canada, tuition for international students in Quebec was subsidized for many years, keeping rates low. In 2018, the Liberal government of Philippe Couillard deregulated the international-student market, allowing universities to charge whatever they wanted and recruit as many out-of-country students as they could. The policy mostly benefited the three English schools, which had access to a far larger global market of English speakers. But Fortin simply suggested more funding for French institutions. He never proposed anything like the CAQ’s plan to siphon international fees to French schools.

The CAQ’s policies are not just about redressing this imbalance. They are about fighting a war many Quebecers want to see waged. The tuition hikes address problems that feel genuine to most people, who don’t want English universities to be better funded than French ones and don’t want Montreal to feel like an alien land where English is king. This latter story is much easier to believe if you don’t live in Montreal—and especially if you find big, diverse metropolises off-putting. Perhaps the only place in the world where Montreal doesn’t enjoy a fantastic reputation is in Quebec.

Last December, I visited the home of Serge Sasseville, the city councillor for the Peter-McGill district, which includes both McGill and Concordia universities, as well as Dawson College. His district is the antithesis of the CAQ’s base of support. As of the 2016 census, more than 16,000 of its 33,000 residents identified as visible minorities, more than 4,000 were recent immigrants and more than 11,000 spoke only English. More than 700 spoke neither official language. When I spoke to Sasseville in his living room, he held up his phone to show me a message from a constituent about Pascale Déry, the province’s minister of higher education. It said that Déry was making it loud and clear that anglophones are unwelcome. “I was born here,” it read, “yet never felt so much like a second-class citizen.”

Sasseville is quick to point out that he is an openly gay politician with a Muslim partner. “That’s Montreal for me,” he says: diverse, inclusive, fabulous. He hates the fact that the government of Francois Legault behaves as if Montreal did not exist, though he doesn’t go as far as some politicians who are actively seeking greater independence from the province. In 2021, a former Alouettes player Balarama Holness founded a new municipal party called Mouvement Montréal. He promised that if elected he would seek from the federal government a kind of multicultural city-state status for Montreal, giving it special taxation powers and exemption from many of the province’s language laws. His campaign was divisive, and the new party won only about seven per cent of votes cast. But, says Sasseville, it garnered surprising support from anglophones eager to be unshackled from a provincial government openly antagonizing them.

Mouvement Montréal will never gain strong support with francophones, but its very existence is a sign of profound frustration among Montrealers who feel their city’s cosmopolitanism is increasingly pitted against Quebec nationalism. That mentality is exemplified in the work of Mathieu Bock-Côté, one of Quebec’s most influential ideologues, who said in an interview last year with online news and opinion website The Hub that multiculturalism amounts to “an identity-gutting operation” for francophones. “In Montreal, they increasingly are living as strangers in their own country,” he said. His book The Empire of Political Correctness—which includes passages decrying “anti-white racism”—has been lauded by Legault.

In both Canada and the United States, visible expressions of nationalism have lately come to be associated with an increasingly narrow spectrum of politics. Think of the Canadian flag, mounted in the back of a convoy protester’s pickup truck. The Patriote flag today holds that position in Quebec. A popular symbol of the Quiet Revolution, it has more recently been adopted by far-right ultra-nationalists. It’s not an uncommon sight on a drive through the countryside in Quebec.

Montreal lawyer Julius Grey is an eminence in the field of Canadian civil rights who was involved in litigation against parts of Bill 101; he has duelled with the Quebec government in courtrooms for decades. “Nationalism is never satisfied,” he warns. “It always asks for more.” Today Grey is part of a multi-pronged legal battle against the CAQ’s new language laws. There are five challenges to Bill 96 before the courts now, and more related to Bill 21.

The CAQ will very probably fight any rulings against its policies all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada, and it could be years before the entire quagmire is resolved. Bill 101 didn’t assume its final form until the mid-1990s; if the challenges to the current laws take that long, their impacts will have become inextricably woven into Quebec society, whatever the rulings are. It is difficult to imagine the situation reversing in the short term.

Though the CAQ’s popularity has been waning, the sovereigntist Parti Québécois has been the beneficiary. PQ leader Paul St-Pierre Plamondon, though he’s criticized the CAQ for springing the tuition hikes without consultation, has not said he’d reverse them if elected—instead, he’s said they are about “equity” with French universities. “When the next election comes,” says Julius Gray, the Montreal lawyer, “there will be a bidding war between the PQ and CAQ over who is going to be more nationalist.”

By January, the anxiety was palpable at McGill and Concordia. Applications hadn’t plummeted as much as feared, but the drops were still huge: 22 per cent for McGill, and 27 per cent for Concordia. “We cannot recall such large decreases in applications in the recent past,” a Concordia spokesperson told the Globe and Mail.

Faculty were sending emails to students to encourage them to sign up early for next year’s classes, lest those courses be trimmed. Everyone was braced for budget cuts. On the seventh floor of the Hall Building, a nerve centre was established to coordinate a three-day student strike. Organizers directed volunteers to picket selected classrooms by standing directly in front of the doors with signs to block professors and other students from entering. More than 11,000 students participated, and around 900 classes were picketed. People hustled back and forth to share information, or else sprawled on the floor to paint signs. Bagels, muffins and tupperware pasta were everywhere. When I was visiting the campuses, I asked every out-of-province student I came across if the policy would have changed their decision to come study in Quebec, if it had been in place when they applied. They all said they’d have gone elsewhere.

In early February, McGill’s president met with Legault, sparking hopes of progress. Weeks later, McGill and Concordia filed separate lawsuits against the government, challenging the tuition hikes. They also asked the Quebec Superior Court to suspend the tuition changes until the suits were resolved. The lawsuits don’t address the francization targets. For now, the universities are still hoping to renegotiate that with the government.

Here’s my advice to English Canadians coming to Quebec: you have to speak French here. You can come for Formula One, for Osheaga, for jazz, and speaking English won’t be a barrier. But living here obliges a person to speak French. Preserving a French society within North America has been an undeniably ambitious project—and one I find inspiring. But the gatekeeping, parochialism and antagonism that accompanies it, around who belongs and who doesn’t, is dismaying. My son will turn five in May. This fall, he’ll enter kindergarten at our local French public school. He’s been speaking French at daycare since he was 18 months old. He prefers to watch shows in French, and he frequently switches between languages at home. I asked Jean-Pierre Corbeil, the Université Laval sociologist who has refuted the notion of French’s decline, if my son would ever be considered a francophone. As far as Corbeil was concerned, yes. But for many Quebecers, he said, “the definition of who is a francophone has an element of identity that tends to be kept in the dark.”

It doesn’t look as if the tuition policy will change, at least not in the short term. And I feel sorry for all the people who won’t come here, who won’t learn French, who won’t go apple-picking in the Eastern Townships or cross-country skiing in Lanaudière. They’ll study elsewhere, start jobs and families elsewhere. I also feel bad for those who might not make their lives here after graduating, like I did. Their kids won’t grow up in North America’s most multilingual city—and yes, it is, with more than 20 per cent of Montrealers speaking three languages or more. All these losses are vivid and personal to me, because I know that if the policy had been made years ago, my whole life, as I know it, would never have happened.

A previous version of this article misstated Serge Sasseville’s position on Montreal’s independence within Quebec.