Finding David Lightning: The decades-long quest to locate an unmarked grave

In 1987, a Cree Elder went looking for his brother’s final resting place. His quest is now a beacon in the search for residential school graves.

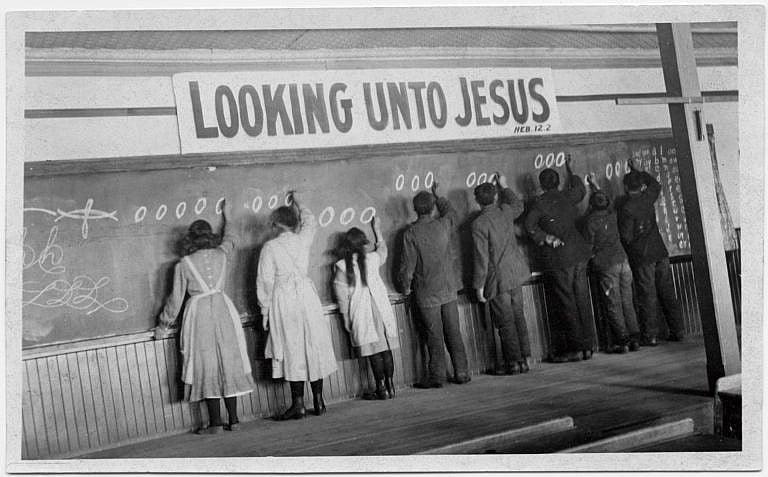

A class in penmanship at the Red Deer Indian Industrial School in the years that Albert Lightning attended. (Courtesy of the United Church of Canada Archives)

Share

The short, elderly man walked into the Red Deer Museum + Art Gallery. Instead of turning left into the exhibit galleries, he veered right, into the staff offices. In the coffee break room, the stern-faced stranger approached a young, burly figure—a fellow Cree working at the museum—looked straight at him and said: “Oh, there you are. You’re the one who’s going to find my brother.”

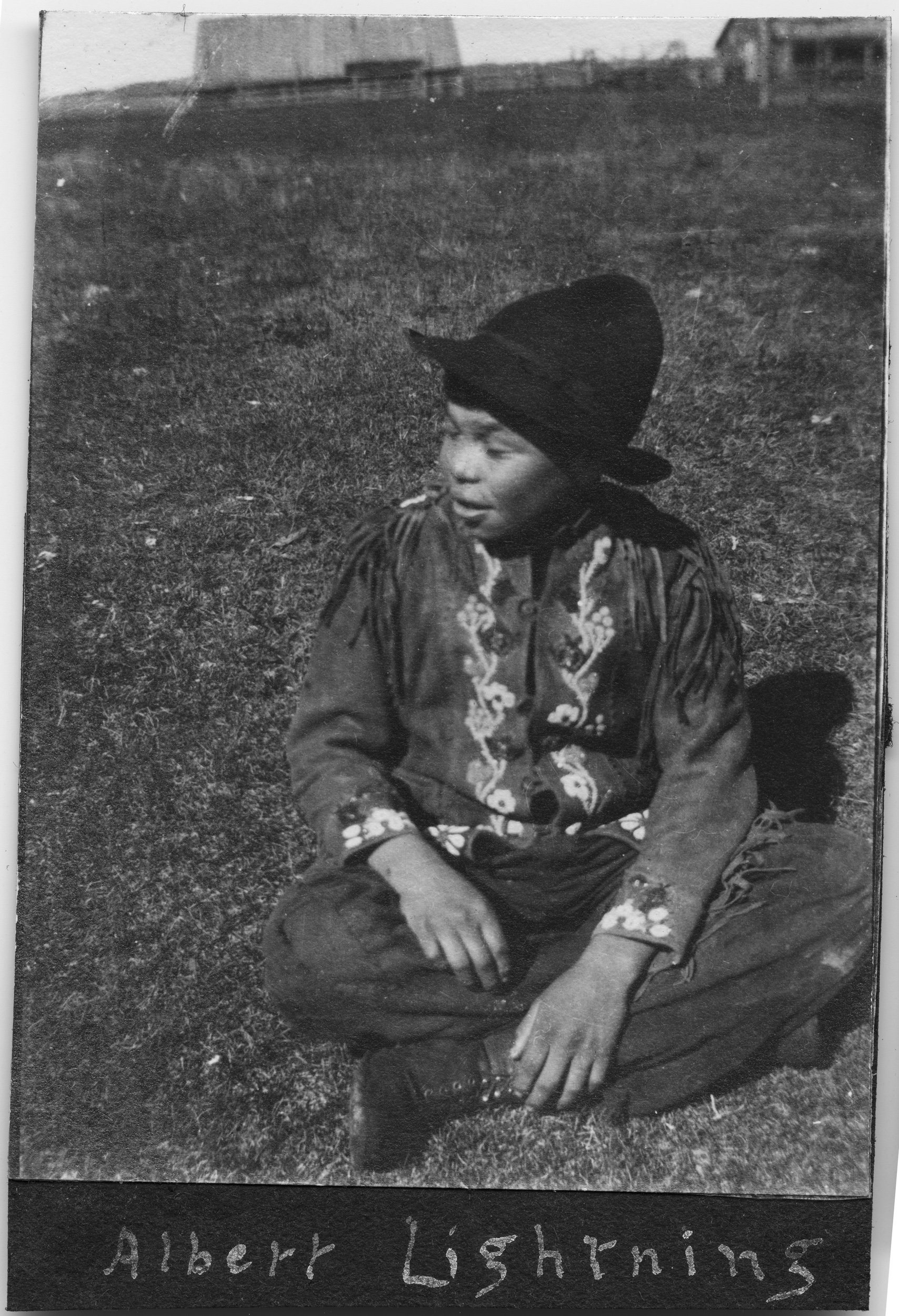

Lyle Keewatin Richards had come across odd characters at the museum that summer of 1987, but this went beyond. The man, an Elder who introduced himself as Albert Lightning, explained that he’d attended Red Deer Indian Industrial School with his younger brother, David, but David never came home. Lightning, 87 and nearing the end of his life, wanted clarity and closure.

That same year, another strange request came to the museum from an old man, this one white. A farmer brought deteriorated wooden markers from the edge of his property—old grave headboards, the farmer explained, from the residential school that had once stood on his property. He wanted the museum to preserve the pieces he’d found decaying in some overgrown brush; Keewatin Richards watched the museum directors, uncertain about the legalities and ethics of accepting old cemetery markers, turn him away.

Then a summer student, Keewatin Richards didn’t initially know that, in Albert Lightning, he had just met a legend. Nor did Keewatin Richards realize that the dual mysteries of headboards and David Lightning’s resting place would become a mission consuming him and several others. In the time before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and long before the recent horror of unmarked graves discovered at Kamloops and other residential school sites, he would help uncover truths that even Lightning’s own family never knew.

Lightning seldom spoke of residential school, and then only in fleeting references during road trips to Calgary, says his oldest surviving son, Richard. “That’s where my residential school was, and that was the pig farm,” Albert would say, head turned to the west as they crossed the Red Deer River. “My brother went there too.” And once, Richard recalls, his dad mentioned something about digging graves with classmates.

***

Albert Lightning may have lost his formative years to an institution designed to, as the notorious saying went, “kill the Indian in the child.” But the rest of his life became a mighty repudiation of that genocidal ambition.

He was born in 1900 on Pigeon Lake Reserve, and taken at age 11 to Red Deer’s residential school, 100 kilometres from home. He attended well into his teens.

Once, when Lightning was out of school, he got lost in the snow near a hillside ceremonial ground. A voice called to him, he’d recall later to interviewers, offering him the choice of two gifts: the “strength and power to be the richest man in the world” or “the gift of spiritual power, knowledge to help people, sick people.” He chose the sacred option, he said, not “white man’s business,” and set out to make use of his gift.

His grandfathers taught him Cree rituals and herbal remedies. After residential school, he ranched in Maskwacis (formerly Hobbema), central Alberta’s largest Indigeneous community, and competed in rodeos. He soon became interested in Indigenous advocacy and leadership, on his reserve and beyond. He was a founding member, and later president, of the Indian Association of Alberta. As leader of a delegation to Alberta’s legislature in 1951, Lightning demanded policymakers give Indigenous people a greater role in the country “stolen from us.” “We should have day schools like all other communities,” he added, “and not residential school.” His own sons had been forced to attend Ermineskin residential school.

Lightning left when the Indian Association began advocating for liquor on reserves, according to the late Glenbow Museum director Hugh Dempsey. From there, he pursued a spiritual path, travelling Western Canada as a traditional healer. “The way I help these people is to take their sickness into my own body,” Lightning told Dempsey. “It’s pretty hard on me sometimes.” Others called him a Cree prophet or “medicine man,” but he referred to himself simply as someone who helps. On a 1976 visit to the Shubenacadie Reserve in Nova Scotia, he helped reintroduce the sweat lodge and other rituals to the Mi’kmaq.

BY CINDY BLACKSTOCK: Screaming into silence

The annual Indian Ecumenical Conferences he helped organize in southern Alberta became popular spiritual gatherings; his youngest sons, Perry and Patrick, each became an oskapios (helper) at ceremonies, while Richard was recruited to erect the enormous 50-person tipi, decorated with buffalo paintings. Albert Lightning’s Cree name was Buffalo Child. He was humble and compassionate, but also stern and stoic. DeAnne Lightning, Richard’s youngest daughter, respected and loved her grandfather, but he wasn’t someone whose lap she could crawl onto. “Mosum was always busy,” she says. “I didn’t want to get in the guy’s way.”

Lightning died at home in 1991, at age 90. Family members recall getting flowers from Ottawa, and condolences from as far away as New York and Australia. Throughout Canada, Lightnings would continue to get asked: “Oh, are you related to Albert?” DeAnne’s sister Gail Lightning, who works as a therapist, encountered this reverence on a work trip to Fort Chipewyan in northeastern Alberta: “They allowed me into their darkest moments because of who my grandfather was.”

Lightning wasn’t the only Elder back then who kept his residential school experiences to himself. And in 1987, nearly seven decades after his brother’s death, no one in his family knew of his search for David.

Yet the following year, he sat for an interview at the Red Deer Museum with Keewatin Richards and a couple of local researchers. Museum staff cannot find any recordings, and have only a partial transcript. In it, Lightning shares the tale of the voice offering two gifts, and offers what may be the only recorded testimonial from a Red Deer Indian Industrial School survivor. “Some boys used to try to run away. They did get away sometimes,” he says. He recounts the story of one runaway who got sick and died before he could find a way home; while a few boys stayed with the body, Lightning says, others fashioned a raft to travel to their reserve to report their friend’s death.

Keewatin Richards and another interviewer, historian Michael Dawe, both remember something Lightning mentioned in the missing section of the interview: “One of the farm instructors,” Dawe says, “was very cruel and quite brutal to the boys who worked in the barn.”

***

The school (centre), student residence and staff house, of the Red Deer Industrial School. (Courtesy of the United Church of Canada Archives)

Red Deer Indian Industrial School opened in 1893, based on two assimilationist notions embedded in the thinking of Canadian leaders at the time. First: Indigenous boys must learn practical trades like farming and carpentry, and Indigenous girls must learn housework. School days were half class, half labour, plus prayer time. Second: children must be kept far from their families. The Methodist-run school was built above a narrows in the Red Deer River, far from any First Nations reserve. In a time before automobile travel, the biggest contingent of students arrived from Saddle Lake Nation, 321 kilometres northeast; a few came from northern Manitoba, 1,469 kilometres away.

It was modestly sized for a residential school, with room for 90 students, compared to 500 in Kamloops (which also started as an industrial school). And while it lasted just 26 years, it was notorious for disease and fatalities: by 1907, 56 students—one-quarter of those enrolled—had died at school or within a few years of returning home, states a master’s thesis by Calgary researcher Uta Fox. The next dozen years would claim another dozen young lives, according to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation’s student memorial. That’s 70 students deceased, among some 350 recorded attendees.

Sanitation was a chronic problem—the school’s sewage system was undersized from the start—and there were outbreaks of tuberculosis and smallpox. Administrators’ requests for an on-site isolation hospital, as early as 1901, were rebuffed by a stingy Indian Affairs department, Fox’s study notes. In 1907, when Dr. Peter Bryce began raising the alarm about illness and conditions in Prairie residential schools, Red Deer had the most juvenile deaths.

Distance from home would compound the tragedy. Only four of the eight students whom missionaries shipped to Alberta in 1900 from Nelson House, Man., survived, records show. During some disease outbreaks, students’ families would camp by the school site, desperate to see their boys and girls. They weren’t allowed.

Red Deer had its share of abusive staff, beyond what Lightning shared in 1988. An Indian agent in 1895* observed a Mr. Skinner smacking a boy’s head with a stick and shoving one girl across the length of the floor. “His actions in this and other cases would not be tolerated in a white school for a single day in any part of Canada,” the agent reported. The principal in 1905 had a preferred punishment for boys, seating them backwards over a chair with their backs bared for whipping. His successor, Rev. Arthur Barner, professed to end corporal punishment and let children return home in the summer. But his racist condescension practically rises from the pages of a 1910 essay he penned for a Methodist magazine. Indigenous children, he wrote, “have no intellectual heredity and as a consequence there is no proper outlook on life; foundations of thinking and reasoning must be laid.” Barner bemoaned the reluctance of Indigenous parents to send their children to a faraway Christian school: “Parental love in the Indian, although crude and animal-like in many ways, is at the same time very strong.”

Joseph F. Woodsworth took the helm of the Red Deer school in 1913, with enrolment declining because families favoured schools closer to their reserves. Both the church and the government had considered closing it, and the likely low point for Woodsworth—brother of J.S. Woodsworth, founder of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, forerunner of Canada’s NDP—came in November 1918, when influenza tore through, infecting most students and staff. “Conditions at this school are nothing less than criminal,” Woodsworth wrote to Ottawa. “The dead, the dying, the sick and the convalescent were all together.”

Four children died in their dormitories from the flu: Georgina House, Jane Baptiste, Sarah Soosay and David Lightning, who was gone at age 14.

READ :What I told my child about the Kamloops graves—to honour the 215

In 1987, Keewatin Richards set out to fulfil Lightning’s prediction that he’d find his brother’s grave, but could find no records that would help him search the overgrown patch of ground that had been the school cemetery. Museum colleagues suggested he try the main Red Deer cemetery, where he found a dusty handwritten register. There, badly misspelled and scrawled on a page mostly reserved for buried stillbirths, was David Lightning’s name. Alongside it were those of the three classmates influenza had also claimed, within days of each other. Plot C73. Unmarked.

Keewatin Richards reported his success in a phone message to Albert Lightning’s home. No reply came.

He later learned why David and his classmates were buried in a town graveyard, kilometres away. The flu of 1918 was so vicious that nobody at the school was well enough to dig graves. At the principal’s request, an undertaker from Red Deer took the bodies. “He gave them a burial as near as possible to that of a pauper,” Woodsworth wrote. “They are buried two in a grave.”

The school closed the following September. The boys’ building was dismantled, its bricks salvaged for a plumber’s office in downtown Red Deer; the sandstone building for girls wound up as a chicken coop, decaying into a ruin that was demolished in 1971.

The cemetery, some 800 metres from the schoolhouses, suffered even greater neglect. Bartlett Moore and his family acquired the farmland through a program for Second World War veterans. By then, only a few wooden headboards remained amid the thicket, weathered and barely legible; a picket fence had largely splintered to dust. In 1987, after the museum turned away his donation of the last four markers, Moore wrapped them in burlap and stored them in his garage.

***

Lyle Keewatin Richards, who was in his 20s when Albert Lightning confronted him in the coffee room, moved on to a career in social work. But questions around the Red Deer residential school stuck with him. How many more dead, lost children were there?

He didn’t attend residential school, but was part of that other scourge that tore children from their parents: the Sixties Scoop. He spent 10 days with his mother before going up for adoption, not seeing her again until the 1980s, when they reunited through Parent Finders. As an adult in Red Deer, cravings for social justice and church-basement coffee brought him to Sunnybrook United Church. One Sunday in 2005, a visiting speaker from post-apartheid South Africa suggested that Canadians had their own truth and reconciliation to pursue. The United Church, formed in a merger including the Methodists that ran the Red Deer school, had by then formally apologized for its role in that system, and a class action by school survivors was nearing conclusion. So Keewatin Richards shared with Sunnybrook leaders something that, as he put it, “I’d kept in my back pocket all this time”: his knowledge of the unmarked graves of David Lightning and untold others from Red Deer’s residential school.

Thus began a renewed search that drew in members of the local historical society; Cecile Fausak, a small-town minister who’d listened as a church liaison to full days of residential school survivors’ testimonials of abuse; and Don Hepburn, a former residential school vice-principal in Inuvik, N.W.T., who left in dismay at that system. Hepburn spent endless hours scanning microfiche, digging through federal documents, church records and old newspapers. He even found a ledger listing clothing the students were lent, with a striking notation alongside the dates when some items were returned: “dead.” Hepburn and his colleagues compiled a list of roughly 350 students and the Indigenous communities they hailed from, records of deaths, plus details of the school’s brutal history. By this point, none of its students was still alive.

This group had little interaction with the owners of the former school and cemetery until 2008, when Doug Moore, Bartlett’s son, applied for a 54-house subdivision on his land. That included the house he built for his own family at the edge of a grain field, 100 metres from the forested burial grounds. Sunnybrook researchers had discussed the school’s cemetery with provincial officials, who required the developer to commission a historic resource impact assessment. Archeologists cleared brush and found several shallow depressions in a 10-by-15-metre area. They used an early version of ground-penetrating radar, and stripped away a layer of soil to discover clear signs of grave shafts and clay backfill. They also found the decayed wooden stumps of headboards, similar to the artifacts that Doug Moore had inherited from his late father. Such surface excavation is rarely done in cemetery research today, says Kisha Supernant, director of the Institute of Prairie and Indigenous Archaeology at the University of Alberta. But one element of that 2008 assessment remains central to contemporary searches for residential school graves: a ceremony like the smudge Keewatin Richards performed before the archeologists went to work. The report estimated there were between 27 and 63 graves on the site, and possibly more in cultivated areas nearby.

READ: ‘At every turn, Canada chooses the path of injustice toward Indigenous peoples’

With the cemetery location confirmed, the Sunnybrook group reached out to First Nations and Métis communities whose children had gone to Red Deer, to share knowledge and determine next steps. Fausak criss-crossed Alberta with student lists and archival photos. At Saddle Lake, she recalls, they knew that grandparents, aunts and uncles had attended the school. “It was kind of like, ‘We’ve been waiting,’” Fausak says. But to many there, and in other First Nations, the list was eye-opening, because so few survivors had spoken of their time there. Former Saddle Lake chief Eric Large found his grandfather’s brother Daniel, enrolled as a teen in 1895. In Samson Nation, Lorne Green learned that the grandfather he never met, Eli, attended from age six to 18. Fausak phoned Nelson Hart, a Cree minister of the United Church in Nelson House, Man., and read him the student list from his reserve; Hart realized his two great-aunts had been sent to Red Deer, and one had died there. “It wasn’t until then that my mother told me her aunts went to that residential school,” Hart says. “I felt sadness that nobody told me about that experience.”

The Sunnybrook group gathered Alberta Elders to visit the cemetery site; among them was Albert Lightning’s youngest son, Patrick, then 56. They resolved to hold the first of four Remembering the Children feasts—four times being the Cree tradition for mourning. In 2010, they gathered 450 people at Fort Normandeau, a historic site on the opposite river bank from where the school sat. Patrick Lightning and Indigenous leaders read the names of every known student who had attended. On a Greyhound bus, Nelson Hart retraced his ancestors’ path from northern Manitoba to Red Deer, a 32-hour trek. After that large ceremonial feast, Elders held a smaller one in a tipi near the cemetery on Moore’s property; they prayed to free the spirits, and tied the four ceremonial printed cloths—red, yellow, black and white—on a nearby tree, instructing Moore to never take them down.

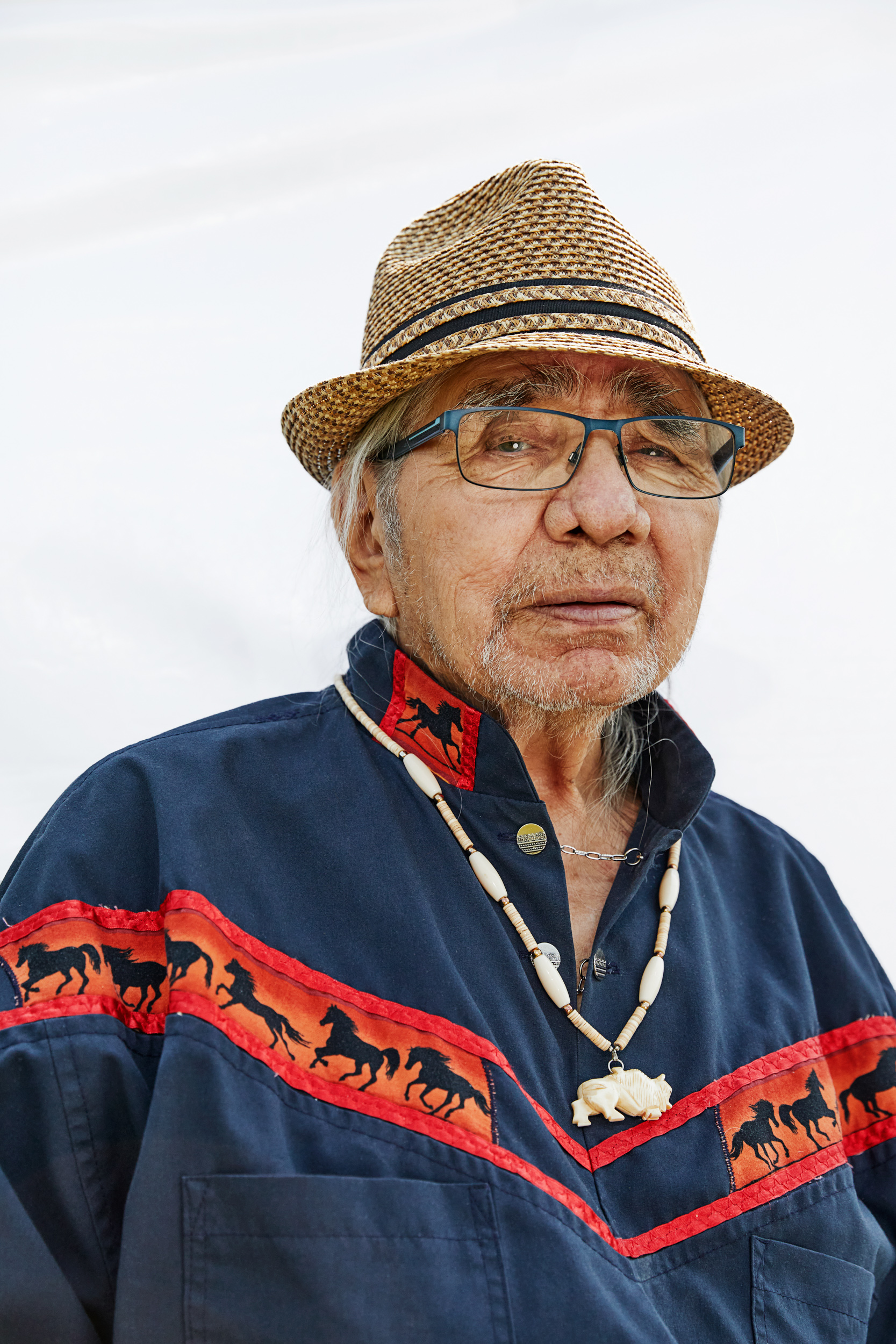

After Patrick had to step back from the organization, his older brother Richard Lightning attended a meeting on behalf of Ermineskin Cree Nation. It was only there, in fall 2010, that he learned about David Lightning’s death and his father’s search years earlier. Richard was shocked. Neither he nor Patrick had heard any of this from Albert. “The feeling was, I could talk to my dad about it, but he’s already gone. So there was no way.”

Richard soon became president of the Remembering the Children Society. When Doug Moore donated the wooden headboards for preservation, Richard and his brother drummed at the head of the ceremonial procession to the Red Deer Museum; Talon, his grandson, marched with one grave marker. Another bears the name of Ellen Hart, the minister’s great-aunt from Nelson House; it’s now encased in a permanent museum exhibit.

The society held the final feast in 2013, to coincide with a Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearing. Richard Lightning, Keewatin Richards and others spoke as witnesses. The commission report extensively quotes them as part of Call to Action 75, which urges government to collaborate with survivors, Indigenous nations, landowners and others to commemorate and document grave sites. The group produced a pamphlet guiding others on the handling of unmarked residential school graves; Fausak would assist on truth-seeking projects for other United Church-led schools in Brandon, Regina and File Hills, Sask.

One act of memorialization remained, though, about which Richard Lightning was quietly passionate. At the Red Deer city cemetery, his Uncle David’s grave lay unmarked. The society finally secured funds for a granite marker atop plot C73 for David Lightning and the three others. It was unveiled in 2017—nearly 99 years after the children were buried. “It means everything to me,” Richard says. “Though it’s 100 years ago, you always keep in mind you’re praying for the souls of those people.”

***

There was a distance between Albert and Richard Lightning that the son ascribes to the hard reality Indigenous people grew up in. At residential school, you were taught to hate, not love, especially when it came to your own culture. His dad likely faced abuse at Red Deer Industrial School. At the Ermineskin school, if he slouched during breakfast, Richard got his ears pulled and his torso yanked backward. “Sauvage!” the francophone nuns yelled at him, he recalled. Parental bonds are hard to maintain when kids spend 10 months a year away. “I never heard him say, ‘Son, I love you,’ ” Richard recalls of his father. “A hug, that’s unknown.”

In early adulthood, Richard moved away into “mainstream society” in Toronto—he briefly drove TTC buses—and returned to Maskwacis with an Acadian wife and young daughters. Back in Alberta, he still could speak the Cree that Albert determinedly used at home. Richard became a translator and research director for his dad’s old group, the Indian Association of Alberta, contributing to a major project revealing how Elders were betrayed by broken government treaty promises. More recently, he’s worked for his tribal council and as an Elder guiding troubled youth. Though Albert never taught him ceremony, Richard picked some up gradually, and he’s often asked to offer prayers at community events.

Tenderness to his own children didn’t come naturally to Richard, but his daughters urged him along. His youngest says he’s a best friend. “Not a lot of people I know have that kind of relationship with their father,” DeAnne says. “If they even have a father.”

Her son, Talon, fits into that camp. Richard has become his de facto dad, she says.

DeAnne went to regular day school, but she understands how the chain of trauma from residential school remains unbroken. “People can take a few different paths when they come out of residential school. You kind of live in a bubble and you just zone out the world. Or you turn to addictions,” she says. She’s lost several nieces and nephews to suicide. “It’s not even shocking to me anymore,” says DeAnne, a food bank manager in Maskwacis. “It’s sad, but not a surprise.”

Much of Albert’s family has strived to defy the core mission of the residential schools. They’ve found the path toward resilience, DeAnne says. They are spiritual, proudly Cree and devoted to family. Richard, proudly sober for 25 years, celebrated his 85th birthday with all three of his daughters in Banff. He wears a small carved buffalo around his neck, a nod to his dad’s Cree name, Buffalo Child.

Lyle Keewatin Richards’ years-long quest: a headstone finally erected for David Lightning and three of Lightning’s classmates (Photograph by Jen Osborne)

***

The Remembering the Children Society has long pushed for its own archeological scan of the cemetery site, building on the 2008 study done for the “Moore Meadows” subdivision, which for economic reasons was never built. Money and support proved elusive, though things may have shifted since the Alberta government acquired the strip of cemetery land in 2018. The province has offered several million dollars for residential school cemetery investigations, reaching out to nine Indigenous communities whose children attended the Red Deer school. Supernant, the archeologist, has been brought in to advise; ground-penetrating radar analysis has improved vastly since the 2008 assessment, she says, and she recommends a wider area be searched.

Meanwhile, David Lightning’s grave in the city cemetery—not only long forgotten but unacknowledged in the first place—is now a revered site. Red Deer city council declares every June 11 as Remembering the Children Day, with graveside ceremonies. Since the Kamloops discovery, visitors have been leaving flowers, teddy bears and toy cars where David and his classmates were laid to rest. To help locals find the memorial in the sprawling cemetery, staff have placed a tall stake next to it wrapped with an orange ribbon. A grave that spent nearly a century unmarked is now marked twice. Buffalo Child might have appreciated that.

*CORRECTION, Sept. 27, 2021: The original digital and print versions of this story said an Indian agent visited the school in 1985; the agent visited in 1895.