A bookkeeper stole $7.6 million from her employer. How did no one notice?

She had her boss’s unquestioning trust—even as she pilfered millions from the Halifax real estate empire she helped him build

Share

July 24, 2023

One morning in the spring of 2021, Sherri Lynn Lamarche left her home in Eastville—a tiny rural community in central Nova Scotia—and climbed into her newly purchased Camaro. She made her usual 80-minute commute, driving southwest into Halifax, where she worked as a bookkeeper in the offices of BANC Group, one of the city’s biggest property developers. She drove into the parking lot just before 9 a.m. Besim Halef, BANC’s 65-year-old founder and CEO, arrived at the same time, returning from an early-morning visit to a job site.

This was his first time seeing Lamarche’s new car—and it struck him as very strange. He knew exactly how much he paid his bookkeeper: $52,520 annually. Watching her cruise into work in a flashy new ride was the last thing he expected. Once inside, he dropped into the office of the company’s vice-president—his son, Alex. He pointed out the car in the parking lot and said, “Do you think she’s stealing from us?”

It was mostly a joke, a knee-jerk response to a situation that didn’t totally add up. He had no reason to think that Lamarche—whom he’d known for 15 years, who dressed in what looked to him like second-hand clothes, who lived in a humdrum corner of the province—had suddenly come into money. He knew she’d developed an appetite for travel, including cruises, safaris and Vegas getaways. But everyone takes vacations, he figured. And anyway, he trusted her, almost unquestioningly.

Like his, Lamarche’s background was modest. She was raised in a working-class community in rural Nova Scotia; he was an immigrant who had arrived decades prior with little to his name. Yes, he’d become one of the city’s wealthiest citizens, but BANC had always been a family business, and he felt Lamarche was practically a member of that family. She’d been doing his books for 15 years, as his company’s deals got bigger, its buildings taller and its cheques fatter. She was nearly his longest-serving employee, and she knew BANC’s finances more intimately than Halef himself. So even though the Camaro was a bit odd, he soon forgot about it. Nothing else seemed amiss.

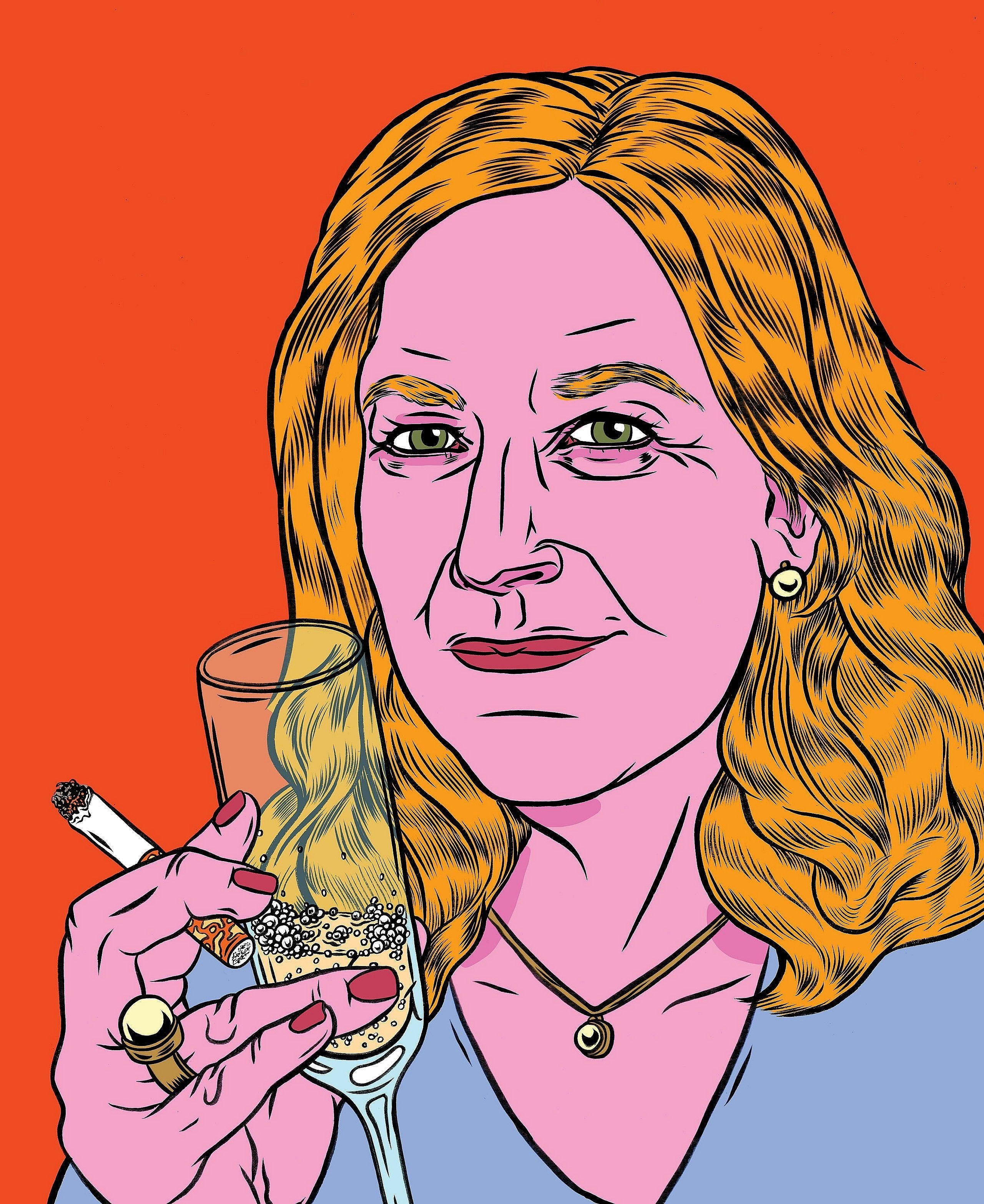

If there were any clues that Lamarche had developed appetites beyond her means—or that her placid-seeming surface concealed anything more nefarious—he missed them entirely. “I would have told you she was a nice, mild person,” says Halef. “Looking back, she’s probably the most cunning person you’ll ever see in your life.”

Lamarche grew up in a world that offered little in the way of luxury. Born in 1967, she had a pleasant childhood, living on the rural outskirts of Halifax with two sisters and a sense of family stability—even if finances were sometimes tight. Lamarche became pregnant with her first daughter, Julia, while she was still in high school. At 21, she met and married Fred Webster, a slim, bespectacled Québécois transplant to the Maritimes. Eight years later, they had a daughter, Jessica.

The couple settled in Clayton Park, a suburban neighbourhood on Halifax’s west side. Webster worked as an equipment technician with the Nova Scotia Health Authority, and Lamarche held a string of jobs, including managing a greeting-card store and answering phones at a Rogers call centre. Despite pulling in decent wages, the pair struggled with money almost from the start. Unpaid bills piled up, and mortgage payments fell behind.

According to a source close to the family, there was a likely reason for their problems. “I don’t remember a time when Sherri wasn’t gambling,” the source told me. “I think she thought it could help win some extra money, and she just got hooked.”

SIGN UP TO READ THE BEST OF MACLEAN’S:

Get our top stories sent directly to your inbox twice a week

It began in the early ’90s with bingo, card games and video lottery terminals. Lamarche would sometimes come home and announce she’d won a small jackpot; her losses were never mentioned. The gambling and financial hardships caused growing friction in the marriage, and Lamarche and Webster split in 2003, after 14 years.

Lamarche found a new home and a new job, at a pizza joint, but her money troubles followed. Electricity was shut off periodically for non-payment. She couldn’t always put enough food on the table. Jessica eventually moved in with her father to escape the dysfunction. At one point, Lamarche’s home nearly went into foreclosure.

In 2004, Lamarche’s eldest daughter, Julia, enrolled in a veterinary assistant program at CompuCollege, a private career college in Halifax. One day, Lamarche was perusing the course catalogue. When she found the page for the bookkeeping program, it seemed a perfect fit: steady pay, regular hours, no prior credentials required. In 2004, at age 37, she enrolled.

It was a lot to handle—school all day, then the pizzeria from 4 p.m. to midnight. But it was at work that she met Shawn Lamarche, an auto body repairman and painter. They got friendly when Lamarche’s car broke down, and he offered to fix it. They soon became allies in a world that seemed to be trying to break them: both had endured divorce, low-wage work and employers who seemed to chew them up and spit them out.

In 2006, shortly before she graduated, CompuCollege contacted Lamarche to say that a local real estate firm was looking for a new bookkeeper. Could they forward her name? The company was BANC Group.

Halifax’s big developers tend to be private businesses run by families. There are the Fares (WM Fares Group), the Lawens (Dexel Developments), the Metleges (Templeton Properties, JONO Developments), the Ghosns (Ghosn Group Developments) and the Ramias (the Ramia Group of Companies), among others. BANC was a family business too. But it was something of an outsider among those better-known names, most of which represent a unique diaspora of families that hail from the same small village in Lebanon, called Diman. The first Diman villager in Nova Scotia, Abraham Arab, arrived in 1894, and many of those who followed became central figures in the development industry.

Halef, originally from Turkey, had no connection to that close-knit Lebanese community. Nor did he have their generations-deep family roots in Nova Scotia. His origin story is instead an up-by-the-bootstraps bit of personal mythmaking that he’ll eagerly share with willing listeners. He arrived in Canada alone in 1975, he says, with only $25 in his pocket. He studied metallurgical engineering at Dalhousie University while working as a dishwasher and cook. After graduating, he got a job as an engineer with a local metal-fabrication business, rising to vice-president. In 1991, when the company went bankrupt, Halef bought it, later changing its name to BANC Metal Industries. The company’s name was an acronym of his family’s initials: Besim and Alex, and his wife and daughter, Nadia and Christine.

As he built a small-scale corporate empire, he kept his head down and trusted no one. He double- and triple-checked everything himself. He eventually owned three steel-fabrication plants across the province, employing around 600 people, and in 1999 he got into shipbuilding, purchasing a shuttered shipyard in the town of Pictou from the provincial government.

All along, he had a side hustle: quietly acquiring property around Halifax. In 2000, when he was 44, he turned his attention to the property game full time, founding BANC Properties. The new entity managed a small portfolio of buildings, and Halef planned to become a developer in his own right. As the business grew, it became clear that it needed closer financial stewardship than Halef could provide. He trusted that Lamarche—seemingly kind and down-to-earth, and a graduate of a well-regarded college—was the right fit to take on the detail-oriented work he’d previously entrusted to himself.

While Lamarche learned the ropes, she and Halef worked closely together in a drab office building near downtown Dartmouth—a cheaper alternative to downtown Halifax, which lay on the other side of the city’s broad harbour. Halef had only four other employees at the time, including his wife, Nadia, who was then the company president. He taught Lamarche how to deal with tenants and vendors, how to receive and file bank statements, and how to cut cheques to contractors.

Over the years, working so closely on a small team, Halef says he and Lamarche developed a friendly relationship that went beyond boss and employee. Lamarche was invited to celebrate family milestones and, when Halef and Nadia went on vacation, he gave Lamarche his keys to check in on the house. In 2007, when her husband, Shawn, wanted to open an auto body business, Lamarche felt comfortable asking Halef for a loan. He gladly lent them $10,000, interest free. The business was called Independent Custom Enterprises Coachworks, or ICE Coachworks. Lamarche handled its accounts and prepared tax returns.

Sherri and Shawn married in September of 2012 and settled in Eastville, outside the city. Their lives became a picture of modest, middle-class comfort: a two-storey house on a generous stretch of land, with well-tended gardens suggesting a green thumb. Shawn drove a beat-up pickup truck and had a beloved Weimaraner. On warm summer days they’d sit outdoors, shaded by an umbrella, smoking cigarettes and drinking beer.

Meanwhile, BANC’s business boomed. The company was building larger and more ambitious projects: luxury apartments downtown, highrises in the city’s gentrifying North End, commercial spaces in the city and suburbs alike. Halef himself ascended to the city’s more exclusive social circles. He joined the board of the local hospital foundation, whose alumni included members of the Sobey family and billionaire seafood magnate John Risley. He wheeled and dealed with politicians. He even played a round of golf with former British prime minister Tony Blair at a business summit organized by former New Brunswick premier Frank McKenna. In 2014, BANC moved its offices to the Craigmore, its first highrise. The Craigmore marked a moment of arrival for BANC—which, by then, employed more than 100 people—as well as for Halef himself. He and Nadia moved into its penthouse, which commanded a view over the picturesque Northwest Arm, an Atlantic inlet on Halifax’s west side.

By 2017, BANC was big enough that enormous amounts of cash were moving in and out of the business. But its checks and balances were still, fundamentally, those of the fledgling outfit it had been just a few years before. Most of those safeguards resided with Lamarche, who worked largely alone. She’d banked years of trust as the company grew under her financial stewardship. She acted as her own oversight, and Halef put almost as much faith in her as he’d once put in himself.

The first time Lamarche stole from BANC, it was easy. She wrote a cheque to her husband’s business, ICE Coachworks, and then created an invoice, marking it as paid to one of BANC’s regular contractors. (Shawn Lamarche appears to have been unaware of her actions.)

She started out small, with sums under $10,000. In January of 2018, for example, Lamarche made a cheque out to her husband’s company for $5,750, but fabricated the records so that it appeared to be a payment to Dexter, a construction company with which BANC did tens of millions of dollars in business. Because her duties included receiving and filing bank statements, she altered them to ensure Halef couldn’t detect her fraud.

Soon, the simple life she and Shawn had built grew more conspicuously lavish. Beginning in the summer of 2018, Lamarche paid down her entire mortgage and then began a series of renovations, which eventually added up to nearly $180,000—a wood deck, a new kitchen, new furniture, electrical upgrades and a new roof.

She also cultivated a taste for travel, taking Carnival Cruises and visiting Uganda, Tanzania and Thailand. She made several trips to Las Vegas, staying at the four-star Park MGM on the Strip. Her children also benefited from her sudden wealth. In September of 2019, Lamarche sent Julia a $30,000 e-transfer. That December, she sent another for $25,000. By early 2021, she was spending out of 10 different accounts and credit cards, functioning as a bank for friends and family and even neighbours. She doled out more than $120,000 over a four-year period.

As she had when she was younger, she justified her big spending by claiming she’d struck a jackpot. And in truth, she spent more of her stolen money on gambling than anything else. Much of it disappeared into the smoking room at the Legends Gaming Centre, a casino just off the Trans-Canada Highway on Millbrook First Nation, near the town of Truro.

Gambling was an escape. At home, no one knew about her crimes, and as she got bolder, she grew fearful of implicating family members. At work, she lived with a growing anxiety about being discovered. Sometimes when a phone rang, or she heard Besim’s voice unexpectedly, her stomach would drop, as she wondered if this was the moment. At Legends, she could vanish into the smoke-filled bingo room, distracted only by her numbers.

Everything changed for Lamarche when she discovered online gaming, on New Year’s Day, 2018. Suddenly she could gamble from home, on her phone—which she began to do almost daily. From mid-January to mid-February of that year, Lamarche spent $30,975 on online gambling. The next year, during the same period, she spent $196,500. The following year, $248,500.

Eventually she was gambling almost constantly, either online or driving straight from work to Legends. If she didn’t go home, she didn’t have to talk to anyone. Her absence placed a strain on her marriage, as Shawn waited for her to return every night; often, he was already in bed when she tiptoed into the house. But no one in her family appeared to question the hours she spent buried in her phone, or the long nights at the casino. They just thought she was lucky.

Between January of 2017 and June of 2021, Lamarche gambled away nearly $6.4 million. She won only $384,000. The losses were spectacular, but for a while, it didn’t seem to matter. The money at her disposal seemed limitless. She was routinely writing five-figure cheques to ICE Coachworks, sometimes even larger ones. In January of 2021, she made a cheque out to her husband’s company for $231,979.73. Her theft, much like her gambling, had become routine—just a part of everyday life.

On June 2, 2021, Halef received a call from Scotiabank. They had flagged a suspicious-looking cheque with a strange signature on it. It was made out to ICE Coachworks, Shawn Lamarche’s auto body shop, in the sum of $69,000. Halef was confused. He didn’t recognize the company—even though he had loaned cash to help start ICE Coachworks, he didn’t know its name. And he thought the company bank account associated with the cheque had been closed. He asked Lamarche, who said the account was open because it was still receiving rent from a tenant.

That didn’t explain what the large sum was about. Lamarche said it was for work done for AtlantiCann Medical Inc., a cannabis business operated by Halef’s daughter, Christine. Halef asked to see the invoice. The amount matched, but it was made out to Maritech Commissioning Works, an engineering consultancy BANC had worked with in the past. At the bottom of the invoice, ICE Coachworks was listed as a division of Maritech. Lamarche said the payee didn’t matter; it was all the same company.

Halef had a creeping bad feeling. Something was clearly off. He called Maritech and learned there was no affiliation between their company and ICE Coachworks—they’d never even heard of it. Halef googled ICE Coachworks, and there it was: Shawn and Sherri Lamarche, co-owners. “You could have taken a shotgun and shot me,” recalls Halef, “and I guarantee there would not be an ounce of blood that came out of my head.”

Lamarche’s moment of reckoning came quietly that same day. She was sitting at her desk when Halef darkened her door. “Sherri,” he said. He walked over, picked up her phone and told her to call TD, her own bank, looking for a full accounting of her personal transactions.

She folded fast. When Halef asked her how much she’d stolen, she only said, “a lot.” She left immediately—assuming, correctly, that her employment with BANC was over.

Halef figured she’d probably only taken a few hundred thousand dollars—a betrayal, to be sure, but a sum he could wrap his head around. It would explain the new car and the vacations. Halef wasn’t sure he wanted to get the police involved, exposing his company to public scrutiny and revealing himself as the victim of an embarrassing scam. Like many targets of financial crimes, he felt stupid that someone had taken advantage of him, as if the theft suggested negligence on his part, happening right under his nose at the company he had built from scratch.

Lamarche made some attempt at restitution, providing a bank draft for $30,000. But she said that was all she could repay. She also signed over her two vehicles—the 2019 Camaro and a 2016 Ford Mustang. She wrote a letter of apology, acknowledging that she had stolen a huge sum of money, and telling Halef that he had been nothing short of a wonderful employer.

Halef and his son, Alex, spent the next two days poring over their accounts to pinpoint exactly how much Lamarche had stolen. They worked backwards, and by the time they reached January of 2017, the total was almost unfathomable: more than $7.6 million, stolen in 328 fraudulent transactions.

They stopped there. Halef didn’t want to know how much worse it got—though he later found out that Lamarche hadn’t just explicitly stolen his money, but also failed to send and collect on invoices, and forfeited rent payments. In one case, she declined payment from a tenant who was $300,000 in arrears. Forty-eight hours after that initial call from Scotiabank, Halef went to the police.

That’s when Lamarche’s contrition turned to defiance. She began reaching out to BANC’s business partners, calling and emailing them in an attempt to besmirch Halef’s name. In July of 2021, she filed a fraud complaint against Halef, claiming he received pandemic assistance he wasn’t entitled to, and that he submitted documents to a federal agency claiming to be an essential worker. (Police reviewed her complaints and found no wrongdoing.) In December of 2021, Lamarche was formally arrested. She acknowledged taking the money, but when police questioned her, she didn’t want to talk about her crimes–she wanted to talk about Besim Halef.

She said his company was horrible to its employees. The family’s business conduct was also unethical—maybe it was they who deserved to be charged, she suggested, for various unscrupulous practices. She even brought a tablet with her to her police interview, on which she had made hasty notes about what she alleged were illegal business activities. She got the sense that the police weren’t interested in her complaints.

In October of 2022, at the provincial courthouse in downtown Halifax, Lamarche pleaded guilty to two counts of fraud over $5,000, and two counts of forging documents. During the hearing, Halef delivered his victim-impact statement. As he stood, microphone in hand, he told the judge he didn’t know where to begin—but his outrage was apparent. “This individual was someone I trusted for 16 years and treated like a family member,” he said. “I guess it doesn’t pay to trust people.” He told the court that he’d endured prejudice, poverty and hardship, but nothing had ever disturbed him as much as Lamarche’s theft. “The betrayal, the anger and violation I felt was beyond anything I had experienced before,” he said.

He sat, and the judge asked Lamarche to affirm her guilty plea, and whether she wanted to address the court. She was confident and casual, betraying no trace of shame, or fear over her impending sentence. “I actually had four pages written,” she said, a touch of insolence in her voice. “There’s no point. I’m good.” Two days later, she was sentenced to eight years in prison.

Today, Lamarche lives not far from the home she purchased with Shawn in 2012, though the couple are now separated. It’s also not far from the Legends casino, where she spent so many evenings gambling away Halef’s millions. The Nova Institution for Women, near Truro, features campus-style accommodation for inmates. There, in a little house, Lamarche lives with a small group of other women, who chat and play cards to pass the days.

I was able to connect with Lamarche in February through her eldest daughter, Julia. We spoke several times by phone, each call divided into prison-mandated 30-minute increments. I wanted to understand why, after building trust for more than a decade, she would betray the man who employed her. And why, even after admitting to her own crime, did she spin spurious allegations, insisting that he was the real crook?

At first, Lamarche sounded upbeat, if nervous. She joked about putting on weight—“the Nova 15”—which she attributed to the prison’s abundant supply of baked goods. She said that she knows she faces grim employment prospects upon her release, as well as a restitution order, which will likely result in the garnishment of any future wages.

I asked her to tell me her version of the story. She began to cry, pausing occasionally to blow her nose—though I couldn’t tell if the tears were of remorse or self-pity. It was a relief, she says, when she was finally caught. And yes, gambling played a role.

But there Lamarche reversed the causal arrow: it wasn’t her gambling that drove her to steal, she insists. Instead, working with the Halefs was so horrible that it drove her deeper into the addiction, which became an emotional refuge. Then she needed more money to feed the habit. “Once it started, it just spiralled,” she told me. “There was no stopping.”

I asked what it was about working at BANC that was so awful, and she repeated the earlier, unproven allegations she’d made against the Halefs, about pandemic-support fraud. She also made new ones: about small-scale corporate misdeeds that she says she, as bookkeeper, was forced to be complicit in. The accusations are specific and detailed, but she has provided no evidence to support them. Halef adamantly rejects them, and they were never used in court as defence; Lamarche’s lawyer specifically recommended she not bring them up. Presumably, the lengthy note she had prepared before for her trial referenced them, but her lawyer advised her not to read it. (Lamarche said she would provide me with a copy of that note; she never did.) I tried to corroborate Lamarche’s new allegations, reaching out to past and present BANC employees, but turned up nothing. Because of that, and because the claims she had previously made were dismissed by police, I won’t describe them in detail.

All I can say with any certainty is that Lamarche’s vitriol against the Halefs is genuine and deeply felt. BANC was not, she insists, a big happy family. (Nadia Halef, Besim’s wife, said in her victim-impact statement that Lamarche was like a sister; Lamarche calls such notions ridiculous.) Yes, she had a key to Halef’s penthouse apartment, but it wasn’t because she was a trusted friend. It was so she could let the housekeeper in when he and Nadia were away.

Even as Halef’s striving paid off—as his net worth soared, as BANC earned its place among the city’s development behemoths—Lamarche remained a bookkeeper with a middling salary. Was it reasonable to think that, after helping build the Halefs’ wealth, she felt entitled to some of the success as well?

Actually, she says, the police asked her the same thing. But she scoffed at them, and she scoffed at me when I suggested it. “I got my TV, and I got my kitchen, and I got my yard and my garden,” she said, describing her pre-incarceration life in Eastville. “That’s all I need.”

I asked her about the hundreds of thousands in home renovations, and the lavish vacations, like one to Tanzania in September of 2018. She dismissed that as a weeklong trip that she won in a bingo sweepstake, to which she added a “little, teeny four-day safari” for her and one of her sisters. (She says she won $100,000 on Christmas Eve in 2018, so they took the same trip again, with the same guide, the following June.) I asked her about the Camaro and the Mustang. Both used, she said. When she signed them over to Halef as part of her repayment, he only got around $60,000 for them in total.

It’s clear that Lamarche struggles to see the Halefs—rich, powerful, well-connected—as victims. She balks at the idea that someone like her is capable of harming a family who didn’t even notice they were missing nearly $8 million. When confronted by police, Lamarche dismissed her theft as a mere drop in the bucket. But the pseudo–Robin Hood schtick—her defiance, her allegations of corporate sleaze, and the largesse she lavished on those closest to her—is undermined by the fact that Lamarche spent most of the money on herself and her addiction, gripping a bingo dabber in a smoky room.

Besim Halef, meanwhile, blames himself. He rarely even checked his own bank statements, and even as BANC grew, its financial guardrails remained that of a small-time outfit.

But Halef isn’t the only boss who’s placed too much trust in one bookkeeper and paid the price. Just last year, an Edmonton court sentenced a bookkeeper named Francis Mella to 10 years in prison for stealing $2.7 million from his long-time employer, a business called Dave’s Diesel Repair. Also last year, a bookkeeper in Timmins, Ontario, named Suzanne Dicaire was sentenced to three and a half years for stealing $2.3 million from her employer of 31 years. “There wasn’t much sophisticated about the fraud,” assistant crown attorney Graham Jenner told the court during Dicaire’s trial. “It was obvious and discovered by the subsequent bookkeeper. But with respect, your honour, these kinds of frauds are often not obvious, because of the position of trust.”

Halef does wonder how those close to Lamarche seemingly suspended disbelief when she told them that the small fortunes she was spending were the result of gambling luck. He’s also planning to launch a civil claim against his bank (Scotiabank) and hers (TD) in hopes of recovering his stolen money. How, he wonders, could they not have flagged Lamarche’s huge transactions as suspicious?

There’s some precedent to give him hope here: in 2017, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that TD and Scotiabank were liable for a $5.5-million fraud committed by an employee of Teva, a pharmaceutical company. The employee opened bank accounts for fake businesses, and over three years deposited 63 fraudulent cheques drawn on Teva’s accounts. In that case, Teva couldn’t sue its own bank because its customer contract stipulated that it was obligated to review its accounts regularly, and flag discrepancies. But it was successful in suing the banks that the employee used to deposit the stolen money.

Halef is less hopeful that Lamarche herself will ever be able to make restitution. “How many people make seven and a half million dollars in a lifetime?” he asks.

There is one thing he’s sure about: if Lamarche hadn’t been caught, she would have grown even bolder. Over the years, the cheques she was cutting to ICE Coachworks grew, from four figures to five figures and beyond. The last two fraudulent cheques she wrote were for well over $200,000 each.

Halef today says the emotional toll of the betrayal weighs on him. It’s eroded the closeness that he once took pride in at his company—in spite of its size, he says, it is still, fundamentally, a family enterprise.

He has gone back to the way he did things in his early years in business: verifying everything himself, trusting no one, eager not to blur personal and professional boundaries. There are no more family events in the office, no more loans to employees. “It just became, ‘You do your work and I do my work,’” he says. “We were not like that before. But she forced us to be like that now.”