12 striking photos you might have missed from 2018

From spearfishing in Belleville to reindeer migration in the Arctic, Maclean’s editors featured each of these photos in our magazine

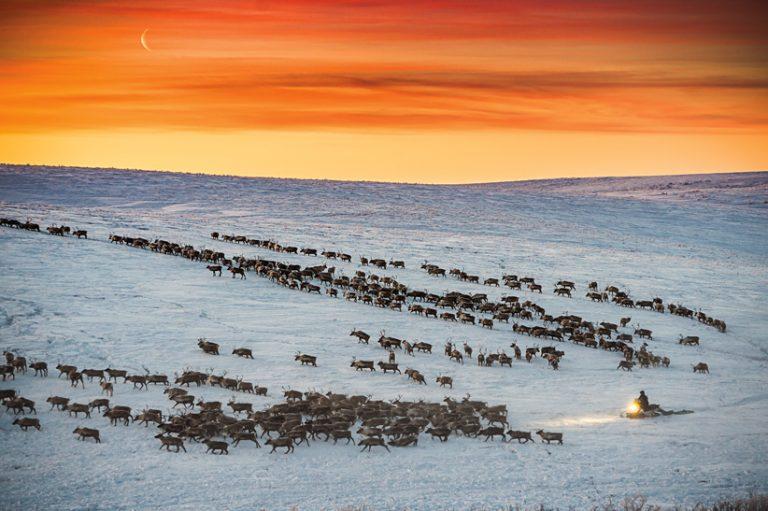

Reindeer crossing

In the early 1900s, the Canadian and U.S. governments made a deal to import a few thousand reindeer from Alaska to the Northwest Territories to provide food and fur for the Inuvialuit of the Mackenzie Delta after a caribou shortage. Now, the 3,000 reindeer—the only herd in Canada—are owned, herded and bred by Canadian Reindeer, a family business, headed by Lloyd Binder, a descendant of one of the men who originally helped bring the deer to the area.

Every spring, the reindeer are herded with snowmobiles between Inuvik and Tuktoyaktuk to their summer breeding grounds. Things will be a little different this year, though. Instead of crossing the ice road, the reindeer will pass by the Inuvik Tuk Highway, a recently-opened all-season road that will connect the towns.

Members of both towns usually gather to watch the migration. Photographer Chris Miller took this photo in January of 2016. He was struck by the animals’ docility compared to their wild cousins, the caribou. That, and the landscape. “You look in one direction and it’s sunset — you look in another and it’s sunrise,” says Miller. “The light’s just amazing. It’s like having that golden hour for hours of the day.” Words by Prajakta Dhopade; Photograph by Christopher Miller

Share

Two years after Target’s retreat from Canada, five million sq. feet of retail space previously occupied by the chain has yet to be filled. Rather than leaving the empty stores to moulder, landlords are reimagining them with new uses. In Niagara, Ont., a former store is now a classroom for students to practise trades. Space in Edmonton’s Kingsway Mall houses local food vendors. And in downtown Hamilton, part of an old Target is now used by the Hammer City Roller Derby. Finding the space means Hammer City hasn’t seen the usual drop-off in members in the winter months, when the team usually practises in a neighbouring city. Triovest, the company managing the property, partnered with community organizers from Toronto to create a new neighbourhood hub, aptly called Right on Target. So far, it has hosted markets as well as the roller derby. Triovest still plans to lease parts of the empty building to new retailers, but it will take time. In the medium term, Hamilton’s former Target has traded in its shelves for spirit and skates. (Words by Prajakta Dhopade; Photograph by Jaime Hogge)

In the early 1900s, the Canadian and U.S. governments made a deal to import a few thousand reindeer from Alaska to the Northwest Territories to provide food and fur for the Inuvialuit of the Mackenzie Delta after a caribou shortage. Now, the 3,000 reindeer—the only herd in Canada—are owned, herded and bred by Canadian Reindeer, a family business, headed by Lloyd Binder, a descendant of one of the men who originally helped bring the deer to the area.

Every spring, the reindeer are herded with snowmobiles between Inuvik and Tuktoyaktuk to their summer breeding grounds. Things will be a little different this year, though. Instead of crossing the ice road, the reindeer will pass by the Inuvik Tuk Highway, a recently-opened all-season road that will connect the towns.

Members of both towns usually gather to watch the migration. Photographer Chris Miller took this photo in January of 2016. He was struck by the animals’ docility compared to their wild cousins, the caribou. That, and the landscape. “You look in one direction and it’s sunset — you look in another and it’s sunrise,” says Miller. “The light’s just amazing. It’s like having that golden hour for hours of the day.” (Words by Prajakta Dhopade; Photograph by Christopher Miller)

Yayoi Kusama may seem like an improbable Instagram star. The 88-year-old Japanese artist is best known for her mirrored rooms, filled with firefly lights or groves of surreal objects. These spaces have now become glittering backdrops for the young and affirmation-hungry on social media, bringing her rising fame.

So as her Infinity Mirrors exhibit comes to the Art Gallery of Ontario—bringing six of her dreamlike chambers as well as a retrospective of her sculptures and paintings—cue the art critics deriding the frenzied selfie-seekers. And yes, the photo-mad risk missing the forest for the polka-dotted trees: The objects in these scenes emerged from hallucinations Kusama has endured since childhood. They represent anchors to reality as she warily approaches fears of annihilation. “I felt as if I had begun to self-obliterate, to revolve in the infinity of endless time . . . and be reduced to nothingness,” she’s said.

Whether visitors lose themselves in the rooms—or instead tether themselves in their phone’s frame—the message is that we all get to choose how close to infinity we want to get. (Words by Adrian Lee; Photograph by Angela Lewis)

Marijuana producer Canopy Growth wasted no time stocking its newest—and now the world’s largest—legal cannabis growing operation in Aldergrove, B.C. The day after its licence was approved in February, the company, which has formed a joint venture with large greenhouse operator BC Tweed, hired a plane to fly 100,000 seedlings from Ottawa to Vancouver. Once there, the plants were loaded into climate-controlled 18-wheelers aptly called “reefers” and trucked under tight security to 12 hectares of greenhouses once seeded with bell peppers. That’s the size of about 14 football fields, under glass. It takes months to go from planting to packaging, so this crop is timed to be ready by midsummer—the minute the recreational market becomes legal. (Words by Adrienne Tanner; Photograph by Jimmy Jeong)

Spring is here, and for thousands of school-aged children across Canada, the new season signals a rite of passage: the annual school track meet. That includes students at Good Hope Colony, a Hutterite community located 100 km west of Winnipeg where Grade 12 student Clara Wollmann, pictured, competes in high jump wearing her traditional dress. The competition at Good Hope features athletes from eight Hutterite colonies in the Portage la Prairie area, with each colony sending around 20 students from Grade 5 through 12. The colonies take turns hosting, and Sandra Wollmann, a teacher at Good Hope, has been overseeing the event since its inception. She organized the first one in 2008, with help from coaches from schools in Portage la Prairie, after noticing the challenges in getting children involved in sports in a small community. (Words by Tom Yun; Photograph by Tim Smith)

When Karina Gould, the first federal cabinet minister to give birth while in office, returned to work on Parliament Hill on May 22 with six-week-old, 14-lb. Oliver in tow, she was greeted with warm embraces and heralded as a political work-life-balance pioneer. Oliver was later ceremoniously carried into a cabinet meeting by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. The landmark moment was emblematic of the support systems behind the minister of democratic institutions’ return after 10 weeks of maternity leave. Gould has a cheering boss in the PM. She says he told her: “We’re going to make this work.” The MP for Burlington, Ont., also has vital backup in her stay-at-home spouse, Alberto Gerones.On Gould’s first day back, father and son watched from the government lobby. Oliver will be by Gould’s side as the politician balances protecting the country from cyberthreats with breastfeeding. For now, diapers sit beside briefing papers in Gould’s office, with a mat by her desk for the baby to stretch out on. When the House rises in June, Oliver will accompany Gould at community events and at her constituency office—trailblazing moments made possible by an equally unprecedented support team. (Words by Anne Kingston and Meagan Campbell; Photograph by Peter Bregg)

Most residents of Belleville, Ont., have never encountered spearfishers on the Moira River. The body of water is traditionally fished by the people of the Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, and the best fishing is after midnight, since the fish are sensitive to light. Photographer and former local Raven McCoy captured Brendan Maracle of Tyendinaga searching for walleye under a downtown rail bridge. Milking the catch and returning the eggs to the water helps sustain the population. “Native people spearfished before Europeans came from the other side of the ocean, have continued to do that ever since contact, and will continue to do so,” says R. Donald Maracle, chief of the Tyendinaga Mohawk Council, noting that Aboriginal and treaty rights—including hunting, fishing and gathering—are recognized in the Canadian constitution. “Harvesting fish is an integral part of our culture.” (Words by Murad Hemmadi; Photograph by Raven McCoy)

It could have been a knockout punch. Noel Harding was in Mexico, readying himself for his next bout only hours away, when he got word that the building beside the boxing club he owns in downtown Brandon, Man., was up in flames. Any hope his gym would be spared quickly vanished. “Right before my fight, I got photos of my roof on fire,” he says. “I pretty much knew my building was going down.” He won the match but returned home to find only rubble where the club he’d owned for 17 years once stood. With nowhere to train his gym’s 50 members—and no insurance to replace what he estimates to be $100,000 worth of lost athletic equipment—Harding opted to hold his classes outdoors. That’s where local photographer Tim Smith found them training four days after the fire; he stood atop his car to capture the moment. “Your eye is drawn to the boxers first,” he says, “and then the devastation around them.” Harding, meanwhile, insists his club will continue—with or without an official address: “It wasn’t the building that made the Brandon Boxing Club.” (Words by Aaron Hutchins; Photograph by Tim Smith)

There really should be more butterflies in this photo. Back in 1996, when monarch butterflies congregated west of Mexico City for their annual migratory journey, they occupied more than 18 hectares of forest. Last year, when this photo was taken, the monarch population spanned just 2.5 hectares. “This is the only spot they go. They’re unique in that sense,” says Emily Giles, a specialist in species conservation with World Wildlife Fund Canada. “But there’s an overarching decline because of a variety of issues: climate change, pesticide use and deforestation.” The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada assessed monarchs as endangered in 2016. But more than a year later, monarchs haven’t received the official designation that would require the federal government to protect their habitat and develop a recovery strategy. Environment and Climate Change Canada says the status of the species is currently undergoing extended consultations, but a final decision will likely have to wait until 2020. If nothing is done to help the monarch population soon, expect more blue skies ahead. (Words by Aaron Hutchins; Photograph by Sylvain Cordier/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images)

Peter Macdiarmid’s images are miniature time machines. They meld archival photographs of the Canadian war effort with his photos of the same locations today. Shooting these images has a way of collapsing time, and leaves Macdiarmid standing in the long-vanished footsteps of wartime photographers. “You can’t help but think about what your colleague from 100 years ago was thinking, what equipment they were using, what they were going through,” he says. The original photos are culled from wire services, Library and Archives Canada and the Canadian War Museum’s collection. Macdiarmid begins with Google Street View, then heads out in person. When he knows he’s in the right spot, it’s a matter of making small adjustments to his positioning—counting windows on the Buckingham Palace facade, for example, to where a gate intersects—to find the exact vantage point from which the historical photo was shot. It is in the contrast between the jagged human destruction of the old photos and the reconstructed cities that now stand there that the aftermath of the Great War becomes clear. (Words by Shannon Proudfoot; Photo illustration by Peter Macdiarmid)

It was how you were reunited with Grandma, that ninth-grade boyfriend you met at Bible camp and your college roommate who never left his shaggy-hair stage. For generations, the Greyhound bus was the ride of choice (usually the only choice) for many people—a lifeline in remote small towns and First Nations communities. On Oct. 31, Greyhound shuttered service across most of Canada, from B.C. to northern Ontario (including Kenora, Ont., where the bus pictured here stopped), citing a long, steep plunge in ridership. On many western routes, smaller carriers have filled in gaps, perhaps with their own scratchy coach seats and gruff drivers whose every break is a smoke break. But several communities will go unserved. And the bus that connected Vancouver to Montreal in three and a half days for $300 (less for students) will never roll again. (Words by Jason Markusoff; Photo by Ian Willms)