The 25 most important people in Ottawa

The Maclean’s 2012 power list

The Peace Tower is seen on Parliament Hill in Ottawa on Tuesday, November 5, 2013. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick

Share

Ask around about the attributes of influence in the federal government during Stephen Harper’s rule. The answers will vary widely depending on who’s doing the talking, but certain elements will pop up with intriguing regularity. Just about everyone, for instance, agrees that power these days tilts westward. And, sure enough, the top three on our list—the Prime Minister himself, inevitably, followed by the chief justice of the Supreme Court and the governor of the Bank of Canada—all hail from Alberta.

Yet Harper had little to do with the rise of Beverley McLachlin and Mark Carney. So is this top-of-the-list cluster of Albertans mere happenstance, or a true sign of a pattern of power? One thing it isn’t, we promise, is a contrivance. Maclean’s writers and editors compiled this admittedly subjective list based on our own combined experience covering Ottawa’s most important people, tested against the sage insights of political strategists, veterans of the public service and lobbyists who make it their business to size up the city’s elite.

What makes one partisan or public servant, public figure or private power broker seem to matter more than another can be mysterious. In some cases, managerial style lifted a figure into our sights, like McLachlin’s subtle touch with the nine egos on the top court, or the way top bureaucrat Wayne Wouters boosts the morale of a public service whose pinnacle he commands. Often power flows in well-worn channels, as through the offices of the finance or foreign minister. Sometimes, though, someone cracks the institutional edifice, and influence streams in unexpectedly. Look at what Kevin Page has done as the first parliamentary budget officer.

Sometimes what matters, at least to us, hardly registers on the traditional scales of influence and power. So we unapologetically assign serious significance to the ability to kick up a fuss in question period or assemble an army of Twitter followers. We believe an ambassador can, if only occasionally, amount to more than the individual whose hand is holding that champagne flute. We insist that an obstreperous backbencher can sometimes matter more than an inconspicuous cabinet minister.

There is no algorithm for tallying up who is important in Ottawa. Yet there’s only one place to begin calculating: from the conviction that the answers, however open to debate, matter greatly. And on that democratic note, welcome to the Power List.

HARPER HARPER |  MCLACHLIN MCLACHLIN |  CARNEY CARNEY |  MULCAIR MULCAIR |  WRIGHT WRIGHT |

BYRNE BYRNE |  KENNEY KENNEY |  LAUREEN LAUREEN |  GEBERT GEBERT |  NOVAK NOVAK |

BAIRD BAIRD |  POILIEVRE POILIEVRE |  LEVESQUE LEVESQUE |  FLAHERTY FLAHERTY |  ANGUS ANGUS |

FINLEY FINLEY |  WOUTERS WOUTERS |  BALTACIOGLU BALTACIOGLU |  RUTHERFORD RUTHERFORD |  GERSTEIN GERSTEIN |

PAGE PAGE |  TRUDEAU TRUDEAU |  HIMELFARB HIMELFARB |  WOODWORTH WOODWORTH |  ZIV ZIV |

01: Stephen Harper

The decider

Seven years after Jean Chrétien was elected, he called a snap election to keep his finance minister, Paul Martin, from quitting and taking half the Liberal party with him. Seven years after Brian Mulroney was elected, his party was bleeding from both ends to two upstart rivals, Reform and the Bloc Québécois. Stephen Harper will reach the seventh anniversary of his election in January, and there is still only him.

The only cabinet ministers he has permitted to rise are the ones whose loyalty is beyond question: John Baird, Jason Kenney, James Moore. Harper makes all the important decisions. Do foreign takeovers of Canadian businesses get approved? Do trade deals go ahead? Will there be attack ads this week? If there is a decision he doesn’t make, that means it was not an important decision.

Harper’s party is united, his voter base solid, his majority immune to assault from the opposition benches. When Mitt Romney lost the U.S. presidential election, just about every pundit in Canada coughed up a column suggesting the Republicans look north for inspiration and course correction.

Harper has become an elder statesman, elected for the first time only two months after Angela Merkel became chancellor of Germany. A decade after he built the Conservative Party of Canada, he is still the one who defines its mission, its priorities, its tone.

And yet this year he has more often demonstrated the limits of his power than the extent of it.

A year ago, the Prime Minister gave up on Barack Obama when the U.S. President delayed approval of the Keystone XL pipeline. But the American electorate declined to follow suit, and now Keystone’s future is back in Obama’s hands. Harper implemented a resource-export pivot to Asia. But public opinion didn’t pivot with him.

And now Harper, who went into politics to fight the Trudeau legacy, must face the prospect of a 2013 during which (at least after the Liberals finally select a leader in April) he could be facing Justin Trudeau every day in the Commons.

By the time he got to New Delhi at the beginning of the month, Harper was beginning to sound a bit like King Canute in reverse, standing at the shore beseeching a new tide of prosperity to come in. “The world’s economy is moving quickly; Canada and India must also,” he told a World Economic Forum event, urging India to act with uncharacteristic swiftness to conclude a trade deal. “Time and tide wait for no one. We must redouble our efforts. Let us not lose the chance for both of our countries that this moment offers.”

Oh well. He still has that majority in Parliament, which means he still has his budget implementation acts, twice a year at hundreds of pages of changes to the way Canada is governed. Each bill cuts spending, curbs the power of the federal government and limits the ability of any future government to return to an activist agenda. Other leaders build monuments. Harper is working to make monuments harder for any of his successors to build. And he still has the luxury he always wanted on his side: time.

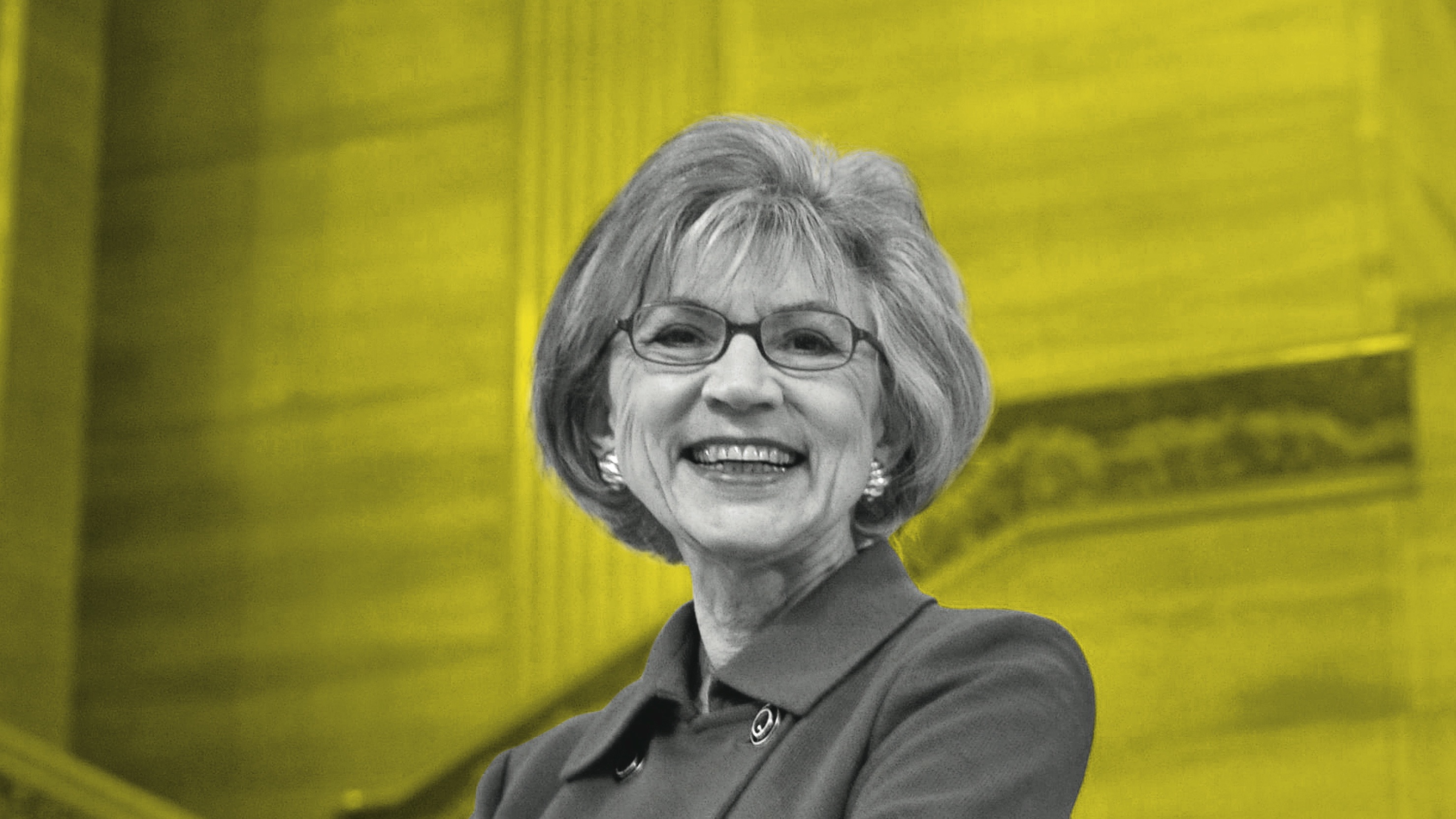

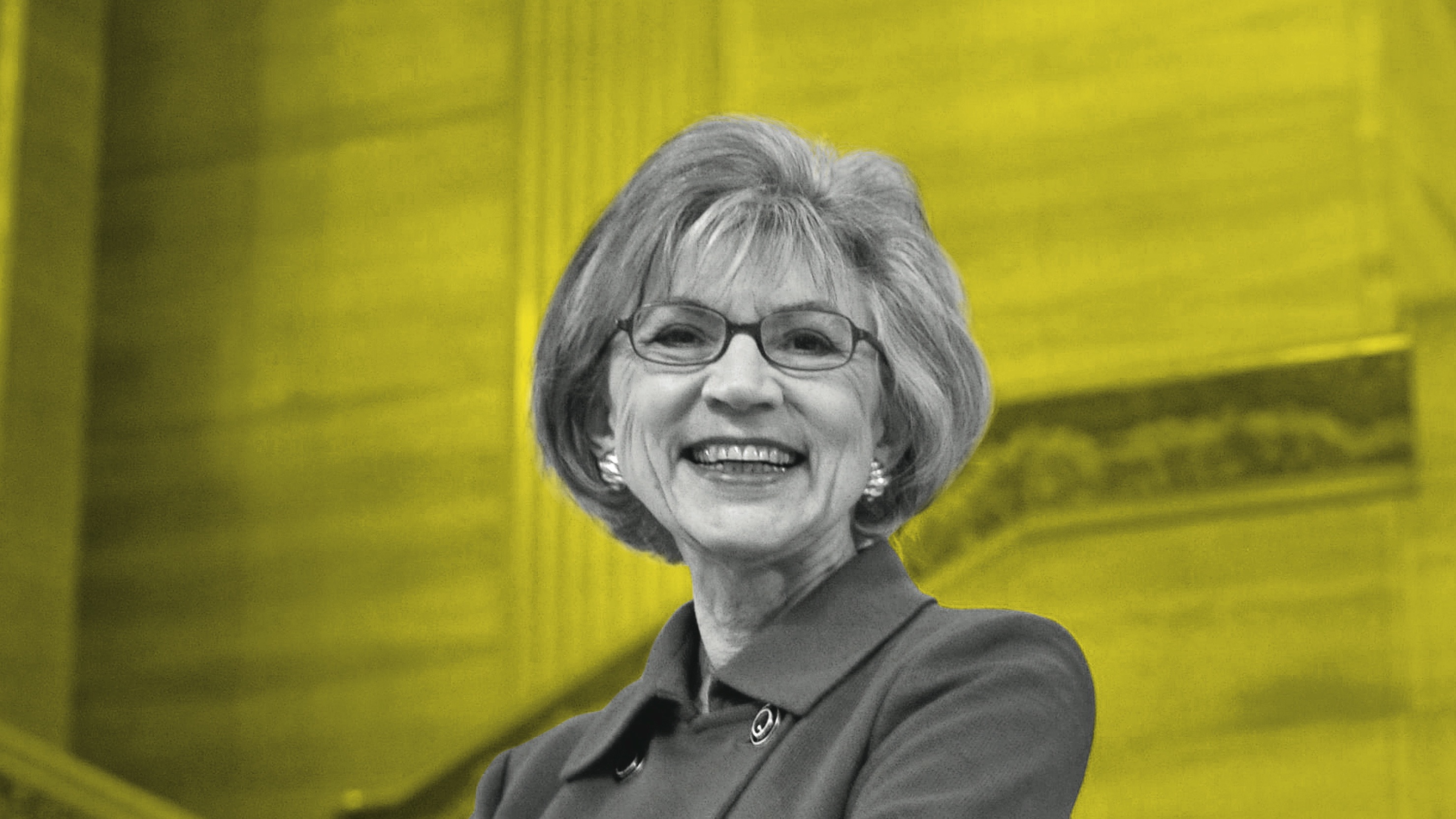

02: Beverley McLachlin

02: Beverley McLachlin

The consensus builder

When she was celebrating 10 years as chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada back in 2009, Beverley McLachlin made an optimistic declaration. The rancorous debate over what’s called “judicial activism,” McLachlin told the Canadian Bar Association, was over. Bitter complaining about unelected judges imposing their will on elected governments, she said, had given way to “recognition that, in a mature democracy of rights, both institutions are vital.”

Two years later she was back in front of the CBA, this time thanking the president of the lawyers’ group for sticking up for an independent judiciary after Immigration Minister Jason Kenney accused judges of undermining the system for assessing refugee claims.

The persistence of tension between courts and politicians is a reminder of McLachlin’s power as the country’s top judge. But in her long run as chief justice, she’s made herself a hard target for politicians, especially on the right, who tend to view judges with suspicion. McLachlin can’t be easily pigeonholed ideologically, and under her leadership, the Supreme Court doesn’t neatly divide along ideological lines.

In fact, its two most politically sensitive recent decisions—first blocking the Harper government from shutting down Vancouver’s supervised injection site for drug addicts, then stopping Finance Minister Jim Flaherty from setting up a national stock market regulator over provincial objections—were unanimous. Accusing the court of a left-leaning bias is tricky when even its Conservative-appointed judges sign on to rulings that thwart Tory aims.

How does McLachlin do it? Seasoned court-watchers credit her with a low-key, consensus-building approach to the complex task of managing the nine-member bench. “She never seems in a hurry, but she gets so much done,” says Eugene Meehan, who regularly argues cases before the court as a partner in the Ottawa firm Supreme Advocacy. But Meehan adds that McLachlin’s quiet, conciliatory manner covers “a fire for the law that would burn through a pouring rain.”

In the Western-oriented Harper era in Ottawa, it doesn’t hurt that McLachlin comes from little Pincher Creek, Alta., where she was born in 1943. Her law degree is from the University of Alberta, but she built her career in Vancouver, teaching law at the University of British Columbia before being appointed a judge in 1981, at just 37. She was named to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1989 by prime minister Brian Mulroney, and was made chief justice in 2000, the first woman to hold the position, by Jean Chrétien.

University of Ottawa law professor Adam Dodek says concern for the real-world effects of judgments is one of McLachlin’s defining traits. Dodek points to her court’s carefully calibrated 2010 decision on Omar Khadr, in which it ruled the government had violated Khadr’s rights, but stopped short of ordering actions that might have looked like the judges dictating foreign policy. Making a point while avoiding an outright clash with the politicians is pure McLachlin. “There is no doubt in my mind that this is absolutely the McLachlin court,” Dodek says, “not only in name, but in style and in action.”

While her demeanour suggests an aversion to open conflict, McLachlin doesn’t dodge the tough issues. When Maclean’s asked her in 2010 about the Harper government’s policy of legislating mandatory minimum prison terms for many more crimes, she flatly rejected the underlying presumption that sentences are too often too soft. McLachlin stressed that the Criminal Code requires judges to aim to rehabilitate offenders, whereas critics tend to view sentencing “only through the lens of retribution.”

The issue of mandatory minimums ranks among the more politically charged questions likely to test her court’s ability to use its power judiciously in the next few years.

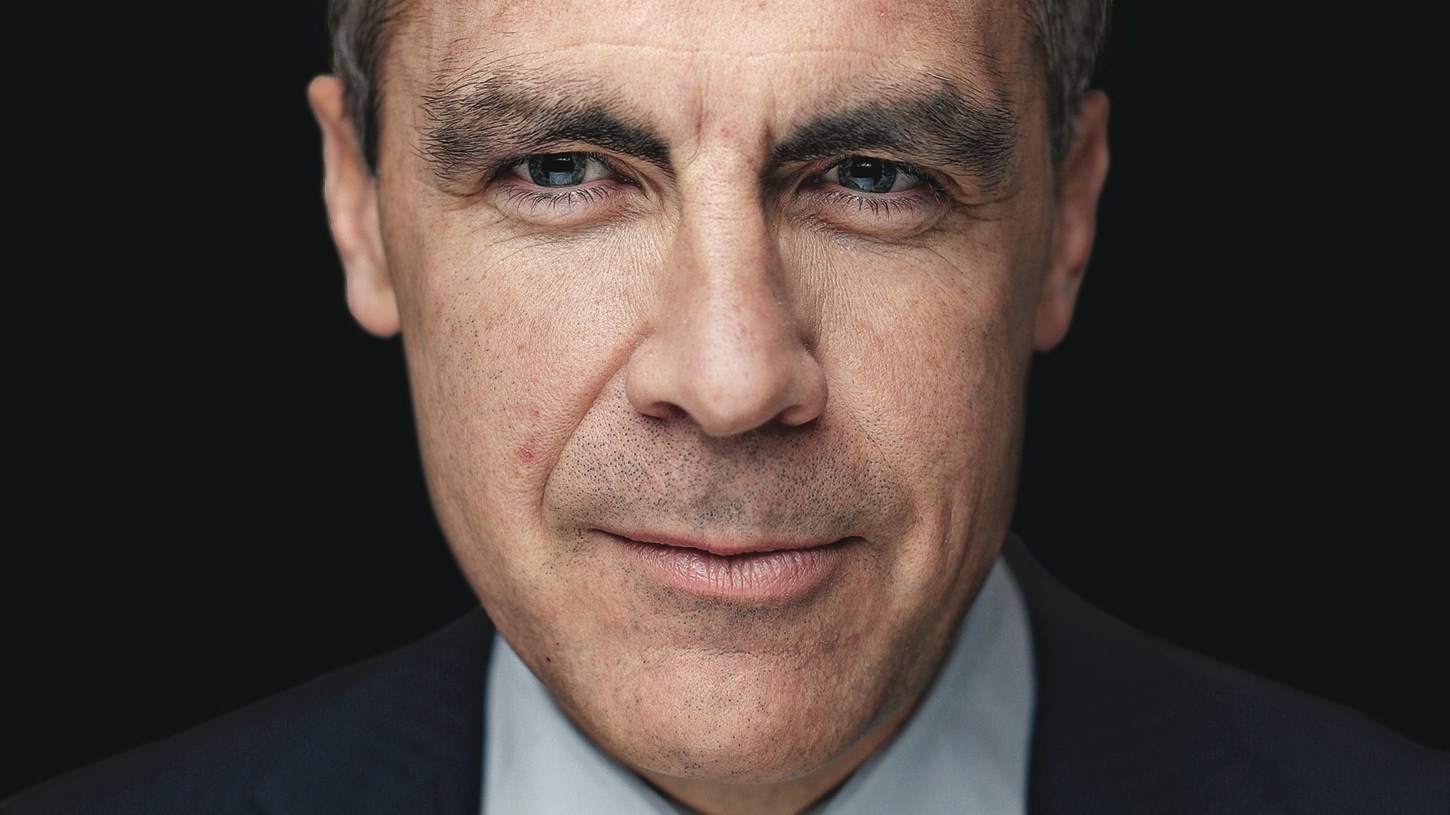

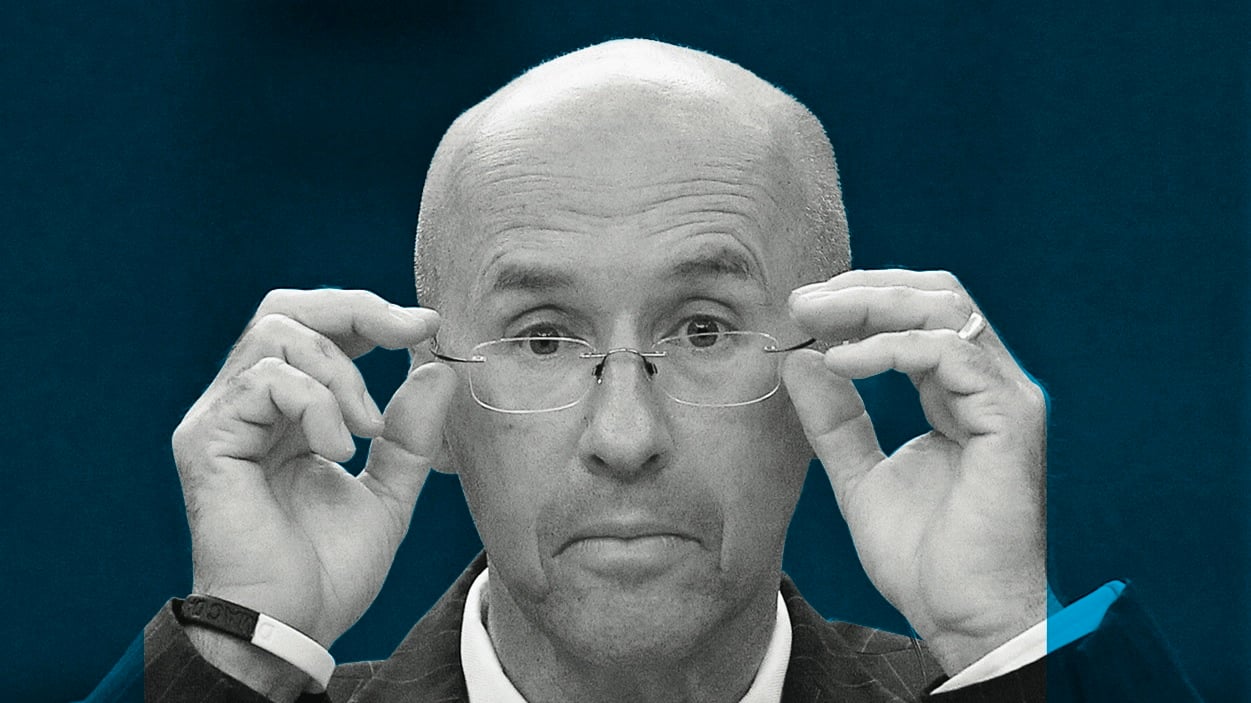

03: Mark Carney

03: Mark Carney

The coaxer

At the moment when he announced this week that he would be leaving Ottawa next June for London, the nature of Mark Carney’s singular form of power suddenly came into clearer focus. After all, his successor as governor of the Bank of Canada will, in all likelihood, continue with much the same interest rate policy as Carney. And the new top central banker will likely keep lecturing Canadians to pay down their household debt. But the next gov is almost certain to fall short of Carney’s blend of international clout and near-flawless presentation. By now, of course, everybody knows that Carney is moving on to become governor of the Bank of England. By his own assessment, he’ll be leaving a Canadian scene where the key political and public-service players were largely in accord behind a clear economic strategy for a more challenging British playing field. Harper and Finance Minister Jim Flaherty will miss the credibility Carney brought, even to a photo-op. They might not miss the way he often outshone them. He’s signed on for a five-year hitch in London. That means he’ll only be 53 when he needs to make his next move, so Carney and Canada might have yet have a future.

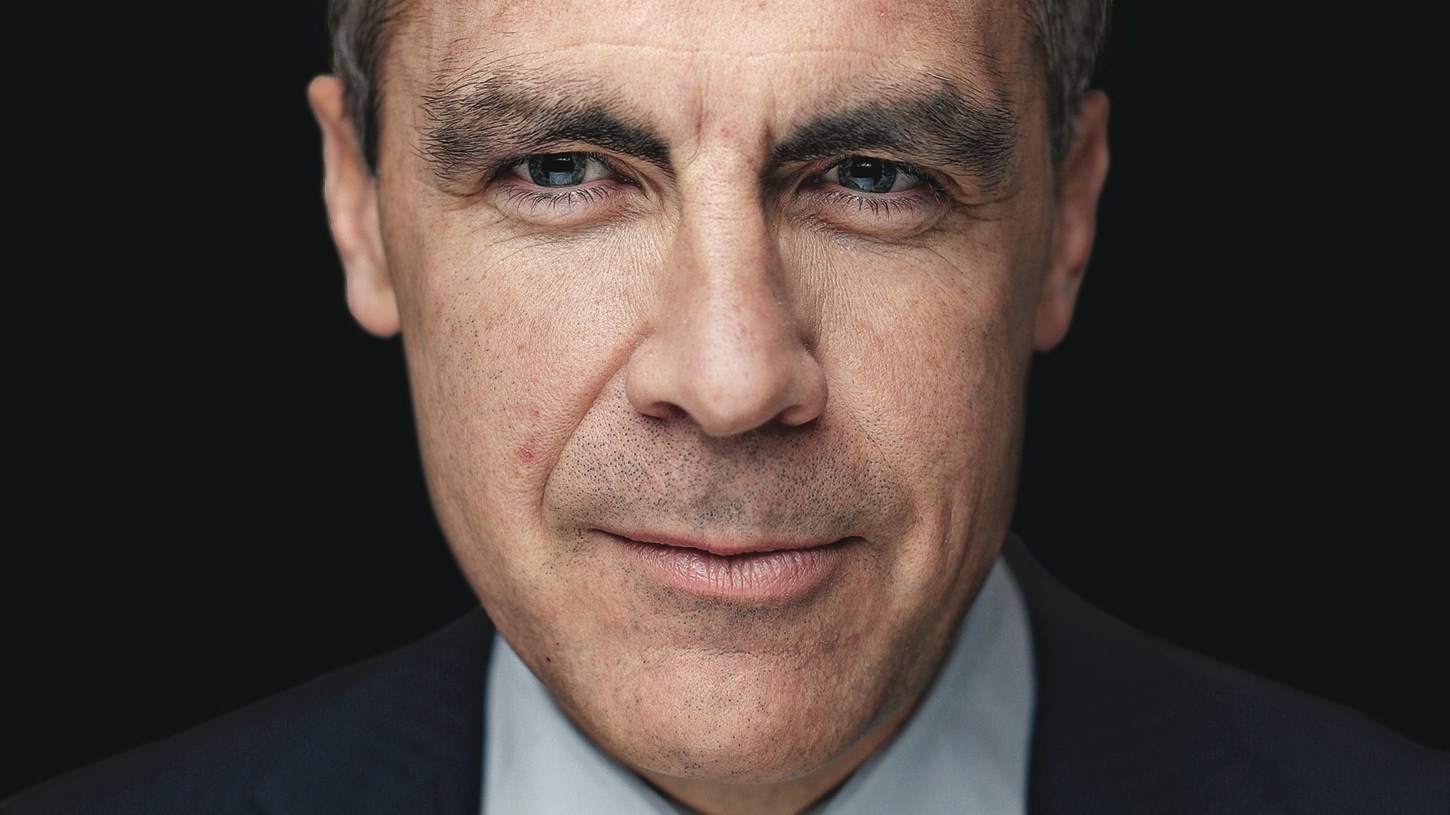

04: Thomas Mulcair

04: Thomas Mulcair

The thorn

The notion that the NDP leader rates a high position on this list irks Conservative strategists. They argue that opposition leaders lost any real power when Harper won his majority in 2011. But focusing on Thomas Mulcair’s inability to fell the government or vote down its legislation would be to take too narrow a view of his influence. By shoring up the NDP’s dominant position in Quebec (bequeathed to him by Jack Layton), Mulcair largely forces the Tories to look elsewhere for growth. By criticizing what he views as lax regulation of the oil sands, he compels the Conservatives to play to their Alberta base, when they might otherwise be cultivating themes that give them a better chance broadening their support beyond. His basic political competence makes the hill the Liberals are climbing that much steeper. Indeed, everywhere on the tactical playing field of federal politics, Mulcair’s presence is palpable. That’s power.

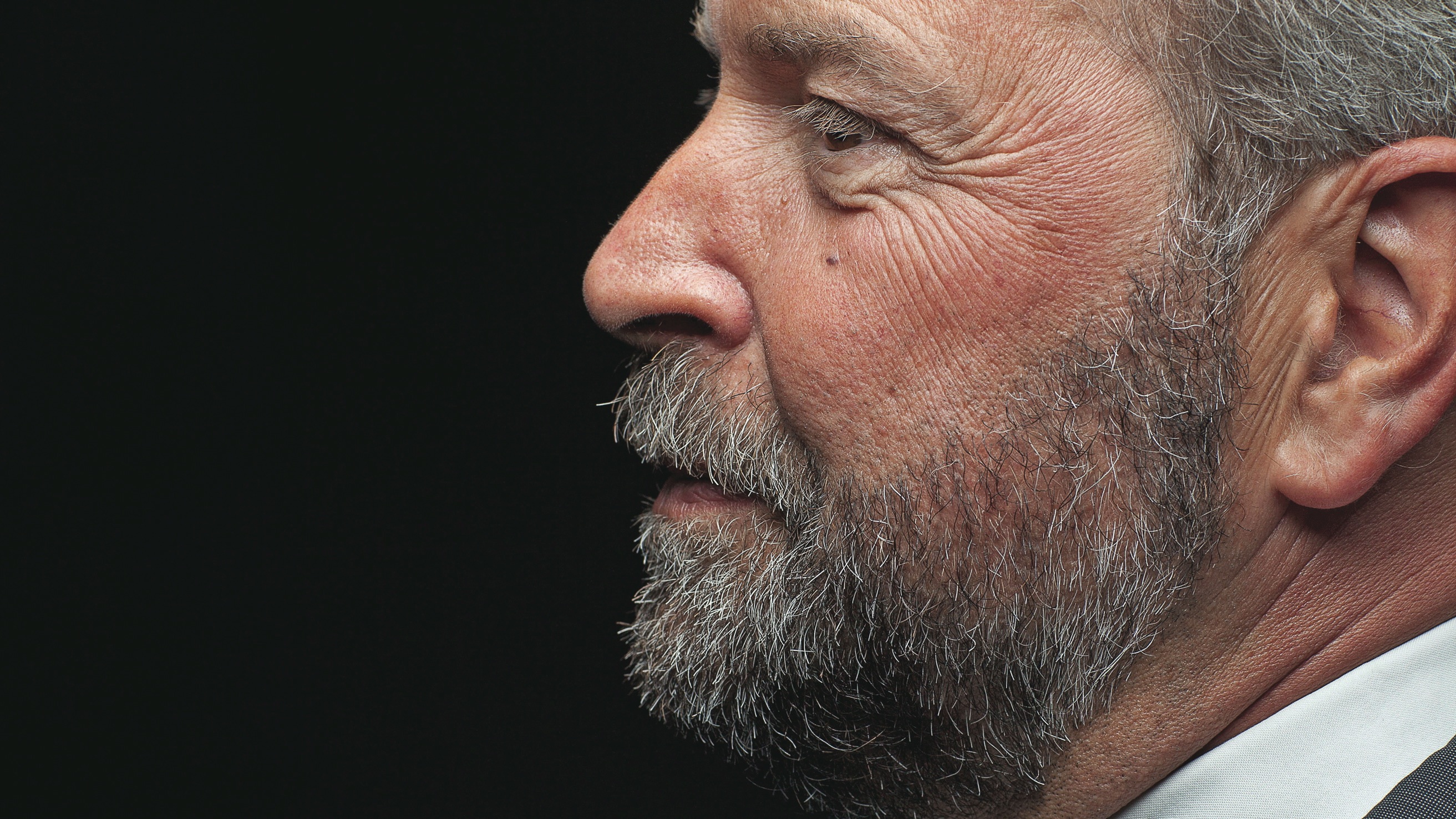

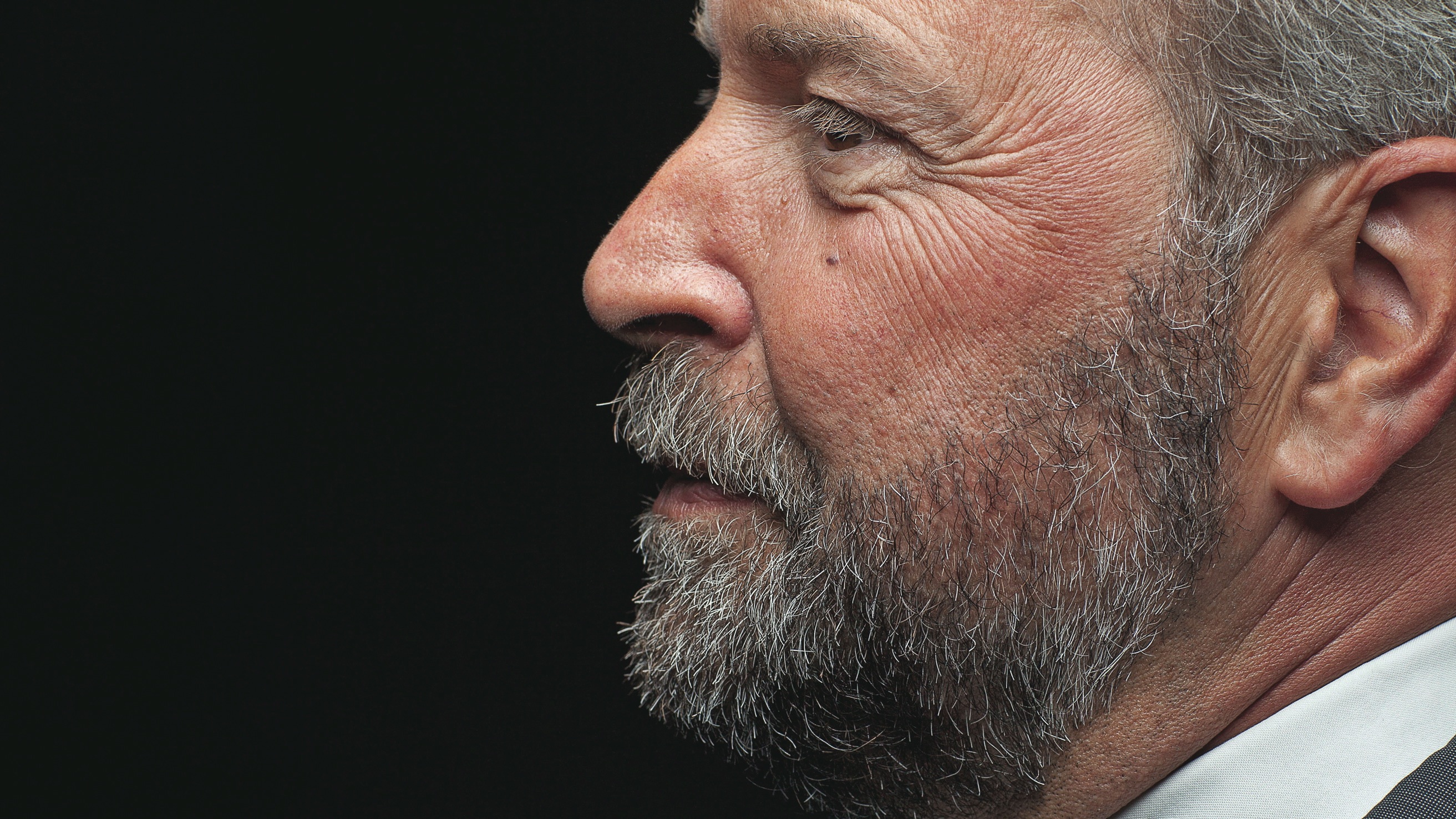

05: Nigel Wright

05: Nigel Wright

The conciliator

The morning papers had brought bad news—a prominent Montreal businessman delivering a scathing critique of a new government policy. And the consensus around the conference table in the Prime Minister’s Office was that the reply should be in kind: a few well-placed leaks to the media to put the spotlight on the executive’s own shortcomings to serve as a warning not to mess with Ottawa. Or at the very least, soften him up as a prelude to negotiations.

It was one of the first decisions that Nigel Wright faced when he took over as Stephen Harper’s chief of staff in January 2011. He took notes as everyone in the room had their say, asking occasional questions. Then he made a statement of principle. Regardless of how things had been done in the past, this wasn’t how the PMO was going to operate on his watch. Instead, the Harvard-educated lawyer turned Bay Street dealmaker went to call the disgruntled CEO. A half-hour later, Wright returned; the man was amenable to talking and had cleared the next two hours of his schedule to work out a deal. The crisis was over by lunchtime. “There were no political fireworks, and no one was damaged any further. The issue was just dealt with,” says one Conservative who was in the room. “That’s the way Nigel is: a success-oriented, behind-the-scenes guy who understands how to play the game, but isn’t out to win at any price.”

Harper’s government hasn’t always been inclined to play nice. Previous chiefs of staff Ian Brodie and Guy Giorno were known for their sharp elbows. But when Harper lured Wright away from a career as a managing director at buyout firm Onex Corp., it signalled a change. The 48-year-old financier has deep Tory roots and had worked in Ottawa before, as a junior aide to prime minister Brian Mulroney, but he’s a bridge-builder, not a demolition expert, the kind of guy who appeals to his boss’s wonkish, policy-driven side, rather than his fascination with the darker political arts.

“I think he’s brought stability to the PMO,” says Charley McMillan, a York University economist who served as Mulroney’s policy guru—and Wright’s boss—in the mid-1980s. “What a prime minister needs most is a surprise-free environment. And Nigel’s not the kind of guy who gets in a panic.”

Recruited as much for his business connections as his management skills, he now functions as a liaison with the country’s rich and powerful. In recent months, he’s met with the CEOs of Scotiabank, BCE, Quebecor, RIM, CN and Vale Canada. However, those ties have also been a source of controversy. In August it emerged he had twice been lobbied by Barrick Gold, a company controlled by the father of a former colleague and friend.

Still, Harper clearly has confidence in Wright’s abilities—earlier this year he raised eyebrows by dispatching his chief of staff, rather than International Trade Minister Ed Fast, to Washington to lobby to join trans-Pacific free trade zone talks. It worked.

The open question in Ottawa now is how long Wright will remain on the job. The two-year leave of absence he took from Onex, and his estimated $2-million salary, will expire at the new year. And with the next election in October 2015 already on the horizon, the Prime Minister will be looking for a long-term commitment.

06: Jenni Byrne

06: Jenni Byrne

The link

One of the mysteries of power under Harper has been how he manages with so little continuity. He tends to churn through chiefs of staff, communications directors and other key aides faster than most prime ministers. But Jenni Byrne represents institutional memory and connectivity between separate components of Harper’s power structure. She’s the Conservative party’s director of operations, keeper of the campaign-strategy flame lit by her former boss and mentor, the now-ailing Sen. Doug Finley. But she also worked inside Harper’s PMO as director of issues management. Nobody else has done such senior jobs in both the party and the government. She is in effect the ultimate go-between, a pivot point for power. And she’s not just trusted by Harper and other upper-echelon players—her background as a teenaged Reform party activist lends her credibility with the party’s rank-and-file true believers.

07: Jason Kenney

07: Jason Kenney

The recruiter

Jason Kenney’s announcements are coming so thick and fast these days that it would be easy to let them blur together: blah blah Jason Kenney blah blah new rules blah. But then you’d miss the peculiar balance he’s struck during the past year as the Harper government’s most hyperkinetic minister.

Watch closely.

“These are the kind of bright young people we are trying to recruit,” Kenney said at the end of October, pointing to international university students standing photogenically behind him at a microphone outside the House of Commons. Up to 10,000 students will get landed immigrant status next year in the Canada Experience Class, a program that admitted only 2,500 in 2009.

A few weeks earlier, Kenney held another news conference to say he was revoking 3,100 fraudulently acquired Canadian citizenships. “We are taking action to strip citizenship and permanent residence status from people who don’t play by the rules and who lie or cheat to become a Canadian citizen.” From 1947 until last year, Canadian governments had only ever revoked 70 citizenships.

It’s a consciously two-track approach Kenney is taking as he makes what Stephen Harper has called “profound, and to this point, not fully appreciated changes to our immigration system.” Some days he rolls out the welcome mat. Other days he plays the enforcer.

“There is no anti-immigration constituency in Canada,” a government source said, explaining what the 44-year-old Calgary minister is up to. “We’re almost unique in the Western world in that there’s no voter support for anti-immigrant sentiment. But there’s a lot of concern about the integrity of the system.” So under Kenney, Canada welcomes as many immigrants each year as under the Liberals—but while it rejects or revokes only a tiny fraction of that number, the rate is far higher than under previous governments.

Kenney’s office is careful to alternate these “pro-immigration” and “pro-integrity” announcements so he never gets too far to one side of the balance he’s trying to strike.

It’s brought Kenney in for criticism, but he has never been shy about a fight. Meanwhile he’s become the Conservatives’ most effective recruiter among immigrant communities, a frequent guest at backbench MPs’ fundraisers, and a power broker whose support will be crucial to any candidate who hopes one day to succeed Harper.

08: Laureen Harper

08: Laureen Harper

The secret weapon

Stephen Harper recently joked that his wife has more modest tastes than Mumtaz Mahal, for whom Emperor Shah Jahan built the Taj Mahal. Laureen smiled at reporters during their trade trip to India and added, “I’m not waiting until I’m dead.” The exchange showed a rare glimpse of the softer side of Stephen Harper, and the casual banter highlighted how Laureen Harper is increasingly the Prime Minister’s secret weapon.

Mr. Harper, an economist, is judged by critics as stiff and arrogant, while his wife, a former farm girl from Alberta who rides motorcycles, hikes mountains and used to compete at barrel racing, is seen as more fun-loving and down-to-earth. She uses that social power to their advantage. She has opened up 24 Sussex to a range of authors, artists and causes—including Ezra Levant on oil, Merna Forster on Canadian heroines and Nazanin Afshin-Jam on Iran. She brought in Heather Reisman and human rights activists to highlight a campaign on stoning.

Mrs. Harper grew up in a political family and met her husband through the Reform party. She is credited for one of the most deft image makeovers: a loyal patron of the arts, she orchestrated her husband’s appearance with Yo-Yo Ma at the National Arts Centre—he surprised the audience by playing the piano and singing With a Little Help From My Friends. It followed Mr. Harper’s cuts to arts funding and criticism from rich artists who gather at galas, like the ones his wife attends.

“When I was active, she used to discuss politics with Stephen frequently,” says Tom Flanagan, a former adviser to Mr. Harper. “But she never sat in on campaign staff meetings. Her influence was always more in the background. She has always had an understanding with Stephen that she wouldn’t talk about policy in public. This isn’t the United States, where the president’s wife can be a semi-independent political figure and take on political causes of her own.”

That may be changing. Last month, Mrs. Harper gave a speech in the Edmonton-Strathcona riding, where the NDP holds the seat. The event, part of a bid to elect a Conservative MP in 2015, was promoted as her “first-ever major public address to a Conservative partisan event in Alberta,” and a call to “restore our true-blue Conservative colours to the entire federal political map of Alberta.”

09: Raoul Gebert

The mobilizer

Back in the early weeks of the NDP leadership race in the fall of 2011, Thomas Mulcair’s campaign seemed hopelessly outgunned by rival Brian Topp’s machine. Then something happened, although at the time few beyond Mulcair’s inner circle knew exactly what. He had recruited Raoul Gebert to manage his bid, and soon began to overtake Topp. After he won the leadership, Mulcair asked Gebert to be his chief of staff. The German-born, Montreal-based organizer was reluctant, but Mulcair refused to take no for an answer. No wonder. Gebert is a seasoned Quebec organizer, and the NDP’s first priority under Mulcair has to be securing its 2011 election breakthrough in the province. His somewhat detached attitude toward Parliament Hill seems to be a tactical advantage. Less caught up in question period and scrums than most, he’s shown more interest in making sure Mulcair travels outside the capital. As well, Gebert is as interested in campaign readiness for 2015 as he is in the daily Parliament Hill buzz. It’s perspective as power.

10: Ray Novak

The gatekeeper

Rarely has a prime minister shown so little interest in surrounding himself with people he’s grown to trust. None of the political aides and advisers thought to be close to Harper from before he won power in 2006 remains in his PMO—except for Ray Novak.

Starting out as Harper’s executive assistant in opposition way back in 2001, Novak basically carried the boss’s bags. Now, he carries some of the government’s most weighty responsibilities and delicate duties. As Harper’s principal secretary, he is, among other things, the key point of contact for foreign governments and provincial premiers. As well, Novak is the guy Harper trusts most to advise him on where he should travel and when.

He is rivalled inside the PMO only by Nigel Wright. While the chief of staff might have more to do with managing the day-to-day affairs of government, the principal secretary manages the moment-to-moment movements of the PM. And there’s history to consider. How to assess the fact that Novak once lived, when Harper was Opposition leader, above the garage at Stornoway? In a regime where personal attachments rarely add up to power, Novak is the standout exception.

11: John Baird

11: John Baird

The aggravator

Leaving Canada’s foreign affairs minister off any list of the federal government’s most powerful figures would have been unthinkable under most prime ministers. Not so during the Stephen Harper era. Past foreign affairs ministers, like Maxime Bernier and Lawrence Cannon, didn’t register. John Baird is different. He came to the post in 2011 having already proven himself as an effective partisan slinger during Harper’s minority governments, and as a can-do transport minister. Since taking over at Foreign Affairs, he’s had measurable impact, forging personal bonds with key players abroad. In keeping with Harper’s shift to closer ties with Beijing, he’s viewed as close to his Chinese counterpart. But the edge Baird is known for in the House doesn’t disappear when he travels outside Canada. He scolded the UN recently for being too caught up in its own internal politics. Not everyone likes his style, but Baird has ended a string of foreign ministers who seemed unable to put their stamp on the job. Power can come from refusing to be ignored.

12: Pierre Poilievre

12: Pierre Poilievre

The brat

No backbench MP gets more face time on national television than Pierre Poilievre. At 32, he’s one of the youngest Conservative MPs. The former Stockwell Day staffer is a firebrand economic conservative who often gets sent to cover for ministers in trouble in question period. That he has the Prime Minister’s trust is shown by how unusually free he is to speak. So we decided to let him speak for himself here.

Q: What is political power in Ottawa today?

A: The ability to get things done.

Q: There’s a school of thought that the only person who has that is Stephen Harper.

A: He shares it with people who are working in the country’s best interest. I’ll give you an example. When I met a soldier in my riding who told me his parental benefits under EI had expired during the time he was serving in Afghanistan—and that he couldn’t extend them, even though prisoners can extend their benefits until they get out of jail—I took up the cause. It wasn’t on anybody’s radar in the Prime Minister’s Office or anywhere else. But by being diligent and hammering away at the political and public service decision-makers, we ultimately got a bill that fixed the problem.

Q: What role does question period play in all of this? That’s where most politically interested Canadians see you at work.

A: It’s the most reported-on portion of the parliamentary proceedings. It sets the agenda for public debate. But I think it gets an inordinate amount of attention. There are a lot more substantive decisions on legislation when it’s on clause-by-clause [review] before committee than there are in the daily question period battle.

Q: After the 2011 election, a lot of commentators said, “Holy cow, this Conservative government can do whatever it wants.” Are you feeling omnipotent these days?

A: Absolutely not. Majority government gives you a chance to fully implement ideas, but you still have to defend their consequences. The main difference is that under a minority, if an idea was momentarily unpopular, it couldn’t be implemented because the government could be defeated before the merits of the idea could be understood. Under a majority government, there’s time for an idea to be absorbed. A perfect example is the increase in Old Age Security eligibility. That was a terrific decision. Because it’s not a populist one, it takes time for the wisdom of the idea to be explained.

Q: In QP, you and Alex Boulerice of the NDP often go after each other hammer and tongs. Do you guys ever go for a beer?

A: We haven’t done that, but we do talk in the halls, and I actually kind of like the guy. I just fundamentally disagree with him.

Q: In a lot of circles your image is as the incorrigible brat of the Conservative caucus—cursing at committee meetings, delivering talking points. Were you surprised to develop that kind of reputation?

A: I honestly don’t mind it. I believe everything I say. The so-called talking points I use are most often things I write for myself. I believe in the government I defend, and when I stand up to defend a minister who’s under attack, I believe in the message. People focus on question period, but I dedicate more of my time to policy development. I was the caucus lead on the platform at the last election. But listen, when it comes time to handle the tough political files, I’m happy to do that too.

13: D’arcy Levesque

13: D’arcy Levesque

The influencer

Is it possible the lobbyist with the most impact in Ottawa actually lives in Calgary? Of course—this is the Harper era. A strong case can be made for D’Arcy Levesque, vice-president of public and government affairs for Enbridge Inc., the company whose proposed Gateway pipeline—which would take oil sands crude across B.C. to be shipped by tanker to Asia—has so powerfully preoccupied the Harper government. Although he’s an energy industry veteran—he helped secure government support that pumped millions into the oil sands—he’s also wise to the ways of politics, as a former adviser to Tory ministers in Alberta’s provincial government. Along with spearheading Enbridge’s clearly close relationship with Harper’s government, Levesque is noted for his courting of elite sympathy through arts philanthropy; he’s the strategist behind his company’s high-profile sponsorship of events at the National Arts Centre, including the Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards, a function much beloved by Laureen Harper. His devotion to the arts, though, is not entirely tactical: Levesque’s mother, who died last summer, was Edmonton landscape painter Isabel Levesque.

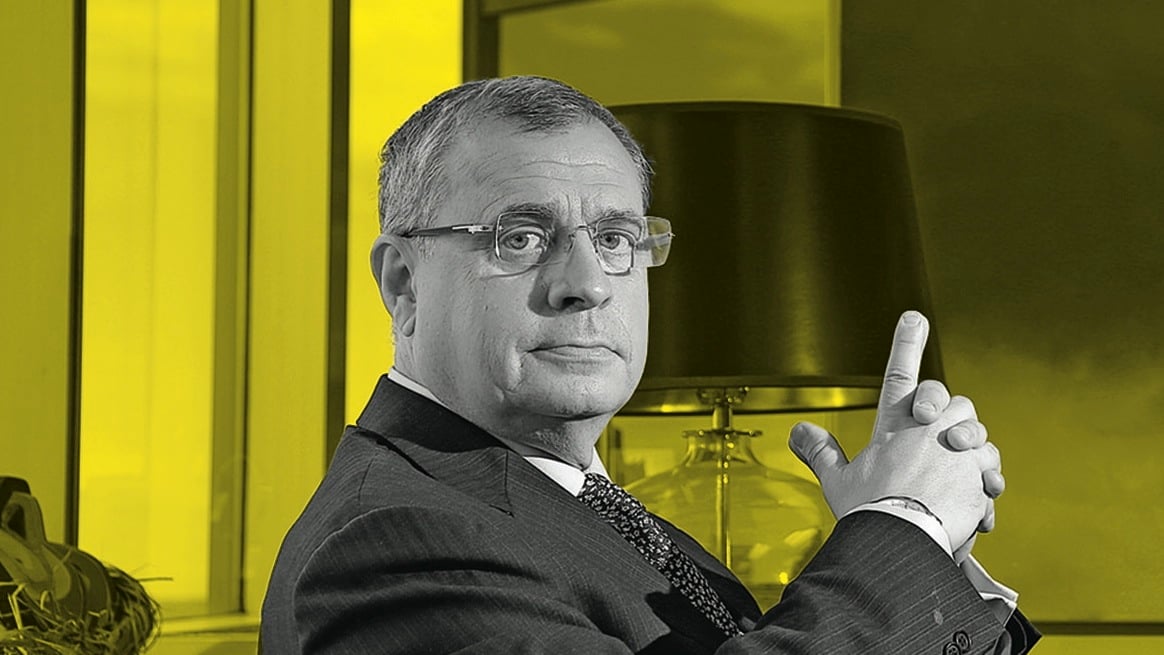

14: Jim Flaherty

14: Jim Flaherty

The steady hand

Only three years ago, he appeared fated to go down as a failed finance minister. Having held the most powerful post in cabinet since Harper formed his first government in 2006, Jim Flaherty is the longest-serving minister (tied with Senate leader Marjory LeBreton). But the financial market meltdown that hit with full force just after the 2008 election, and the recession that followed, threatened to reduce him to a political casualty of an economic catastrophe. After all, he’d promised no deficits—then delivered a gusher of red ink. Yet Flaherty not only survived, he thrived. The massive taxpayer-funded ad campaign that accompanied “Canada’s Economic Action Plan,” and continues to this day, salvaged the government’s popular reputation for reasonable economic management and, by extension, Flaherty’s own credibility as Harper’s point man on the file. These might be trying times, the narrative goes, but Canada has outperformed comparable countries. Flaherty’s Irish smile has weathered into a perpetual look of strain, but he’s remained the Tory face of economic resilience. And he’s settled in for the long haul as the closest thing to an indispensable minister in Harper’s cabinet.

15: Charlie Angus

15: Charlie Angus

The antagonist

If there is an art to being an opposition member of parliament, it’s to be found at the intersection of policy wonkery and partisan acrimony. Charlie Angus lives at that crossroads. He delves deep into files like Aboriginal affairs and election spending rules, but sees everything he learns through an NDP-orange lens. He’s also a former rock musician who knows how to perform before a big audience.

The biggest of each day the House is sitting comes during question period. Angus has turned himself into a master of QP timing and delivery. He personally pushed the lousy-housing plight of Attawapiskat, a reserve community in his northern Ontario riding, onto the front pages. More than any other opposition MP, he took media revelations about dubious Conservative robocalling tactics during last year’s federal election and converted the story into many days of QP drama.

For any ordinary MP to succeed in putting himself at the centre of debate on so many days would matter. Provoking the government into taking action, as Angus can boast to have done on multiple occasions, matters even more.

16: Diane Finley

16: Diane Finley

The reformer

Even her fans don’t claim that the minister of human resources and skill development is a natural charmer. But in the run-up to last year’s federal budget, government sources say, no other minister was so prominent at cabinet meetings. After all, Finley’s sprawling department runs both Employment Insurance and Old Age Security. Harper had targeted both programs for significant, controversial reforms. It’s doubtful he would have tried with a less trusted minister in charge. Finley has come under intense fire from critics on both files, but remains unflappable. Her reputation among insiders is mixed. Tories praise her. Bureaucrats and lobbyists, not so much. She’s married to Sen. Doug Finley, the architect of Harper’s election strategy before he was largely sidelined by illness. But Diane Finley is a force to be reckoned with in her own right, the key voice on the government’s most contentious domestic policy files.

17: Wayne Wouters

The mandarin-in-chief

Maybe it’s fanciful to imagine it matters much that the clerk of the Privy Council, the top federal public servant, was born in tiny Edam, Sask. But in a government that prides itself in thinking outside the Toronto-Ottawa-Montreal triangle, and in which Prairie roots confirm bragging rights, it can’t hurt. Appointed mandarin of mandarins in July 2009, Wayne Wouters started running the show when that year’s stimulus spending was rolling out. It was a hectic, anxiety-ridden period for the Harper government. An economist by training, unflamboyant in the classic career public servant mode, he has few detractors. So far. But as the government proceeds with paring public sector jobs across many departments, his reputation will be tested. He’s made a point of cheerleading for the “collective accomplishments” of the public service. There are rumours that he might soon retire, but for now, he remains solidly in place and stolidly powerful.

18: Yaprak Baltac?oglu

18: Yaprak Baltac?oglu

The action planner

The toughest test Stephen Harper’s government has so far faced arguably came in the weeks immediately after Finance Minister Jim Flaherty tabled his 2009 budget. Rushed out that January as a global recession took hold, the emergency spending plan earmarked $4 billion for local and regional infrastructure projects and plunged Ottawa back into deficit. The task of shovelling that money out the door fast enough to dull the edge of the economic downturn fell to John Baird, then minister of transportation and infrastructure. But to manage the unprecedented spending spree, he would turn to Yaprak Baltacioglu, his deputy minister and already a rising figure in the federal bureaucracy.

Success in fast-tracking billions in infrastructure spending without major scandal or charges of serious mismanagement boosted both minister and deputy. Baird is, of course, now Harper’s foreign minister. Baltacioglu, as befits a mandarin, keeps a lower profile. Still, among Ottawa insiders her name resonates, even if few can pronounce it. (For the record, it’s YAP-rak Bal-ti-CHOO-lu.) She has a reputation for public discretion but behind-closed-doors bluntness. “What has made her a success is that she’s a straight-shooter. She doesn’t sugar-coat,” says Goldy Hyder, a well-connected Tory with the lobbying and consulting firm Hill and Knowlton.

Baltacioglu was born in Turkey and came to Canada when she was in her early 20s, about 30 years ago (the Treasury Board’s media office would not release her age or say what year she immigrated). She arrived with a law degree from Istanbul University and added a master’s in public administration from Carleton before joining the public service in 1989. She rose through posts in agriculture, environment and the Privy Council Office, the bureaucratic nerve centre that supports the Prime Minister’s Office. A few years ago she married Robert Fonberg, now deputy minister of defence. He’s Jewish, she’s Muslim. But as a public-service power couple, they stand out more for their combined clout than their personal profiles.

Harper’s senior strategists have been singing Baltacioglu’s praises ever since she implemented the 2009 stimulus program. When a shake-up of top mandarins was announced in early October, Harper appointed her secretary to the Treasury Board, making her the top bureaucrat at the central agency in charge of the government-wide cost-cutting exercise overseen by Tony Clement, the treasury board president. One Conservative strategist said she is not expected to argue for any strong set of ideas about what parts of government should be trimmed or protected. “I don’t think she has a deeply held agenda,” the strategist said. “She’s something of an opportunist who seizes the moment.” And, not for the first time in the Harper era, Baltacioglu’s moment seems to be now.

19: David Rutherford

The conduit

It’s not unusual for a prime minister, especially after a few years in power, to develop a strained relationship with the media. But Harper’s Conservatives are unique in having been encouraged from the outset—by Doug Finley among others—to regard the mainstream media as their natural, eternal enemy. The upshot is that finding national media figures with truly close relationships to political power in Harper’s Ottawa is uncommonly difficult. But there is an exception. When Harper needs to put the message out to the right-wing faithful, he can count on populist radio legend Dave Rutherford. It’s in Rutherford’s Calgary QR77 studio that Harper regularly finds a comfortable forum for sending a relaxed message to his core supporters. Yet Rutherford doesn’t indulge in empty-headed boosterism. When Harper dropped by to talk last summer, Rutherford raised the issues of the European economy, worrying personal debt levels in Canada and public service cuts. Not an inquisition, but surprisingly substantial for talk radio. For Harper, the value is clear: he gets to convey seriousness without being grilled. For Rutherford, there’s the power of serving as the link between the PM and many of his more reliable backers in his hometown market.

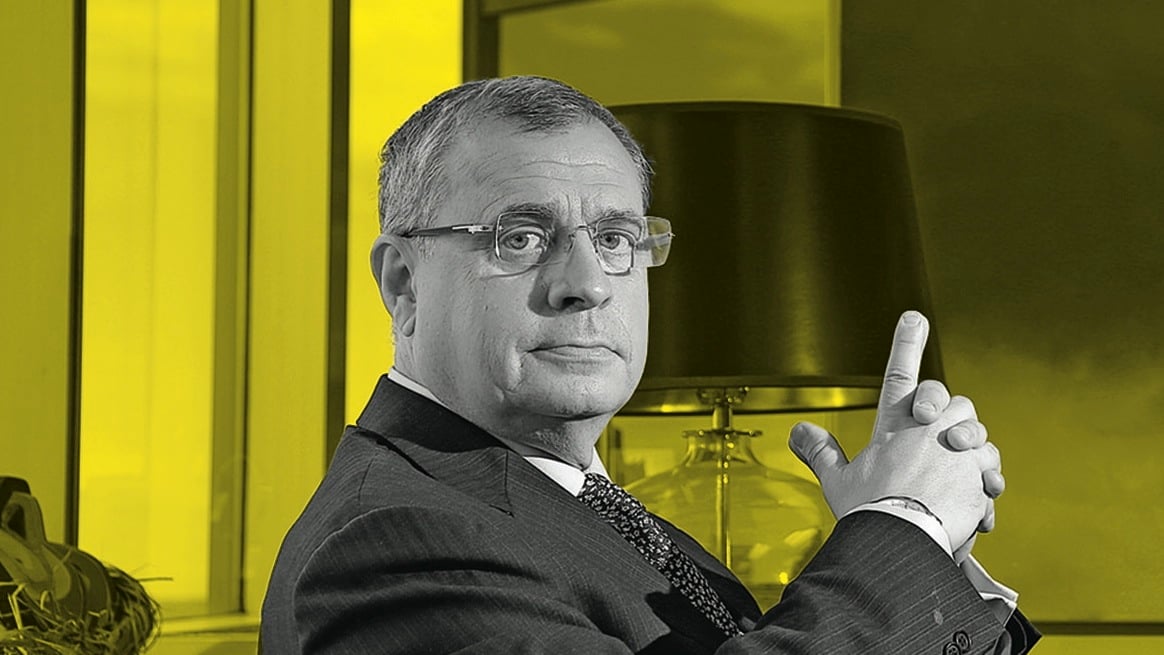

20: Irving Gerstein

20: Irving Gerstein

The fundraiser

The numbers are stark. Since 2005, the Conservative Party of Canada has raised close to $145 million in public donations at the national level. Over the same time, the Liberals managed less than half that sum. The NDP, just $40 million. It is a testament to the Conservative party’s support, but also its biggest advantage in this era of the permanent campaign. And for as long as there has been a Conservative Party of Canada, the chair of the Conservative Fund has been Irving Gerstein.

The party’s fundraising success is not built on the depth of donors’ pockets, Gerstein told the Conservative party convention in 2011, but on the breadth of its donor base. “To raise money successfully, a political party must appeal to a large number of Canadians of ordinary means,” he said. “That is still what some parties do not understand, and that is why some parties are lagging behind.”

The party’s haul is a triumph of messaging, but also technology. One insider notes the computerized lists of contributors Gerstein has overseen are at the core of the party’s system for tapping volunteers and votes. Gerstein credits the party’s database for the election of 40 Conservative MPs during the last election.

The former president of Peoples Jewellers (his grandfather founded the company) Gerstein previously chaired the Progressive Conservative party’s fund. Stephen Harper nominated him for the Senate in 2008. As part of the in-and-out scandal, Gerstein was one of four Conservative party officials charged under the Elections Act. (The charges were dropped when the Conservative party agreed to pay a $52,000 fine.) Ian Brodie, a former chief of staff to the Prime Minister, lauds Gerstein as “the single best political fundraiser any party in Canada has ever had,” one who has seen various changes to fundraising laws and methods over the years. “What’s his secret? There is no secret. He works hard every single day and never lets go of an opportunity to ask,” Brodie says. “Some call him shameless. I call him persistent. I literally don’t know what Mr. Harper would do without him.”

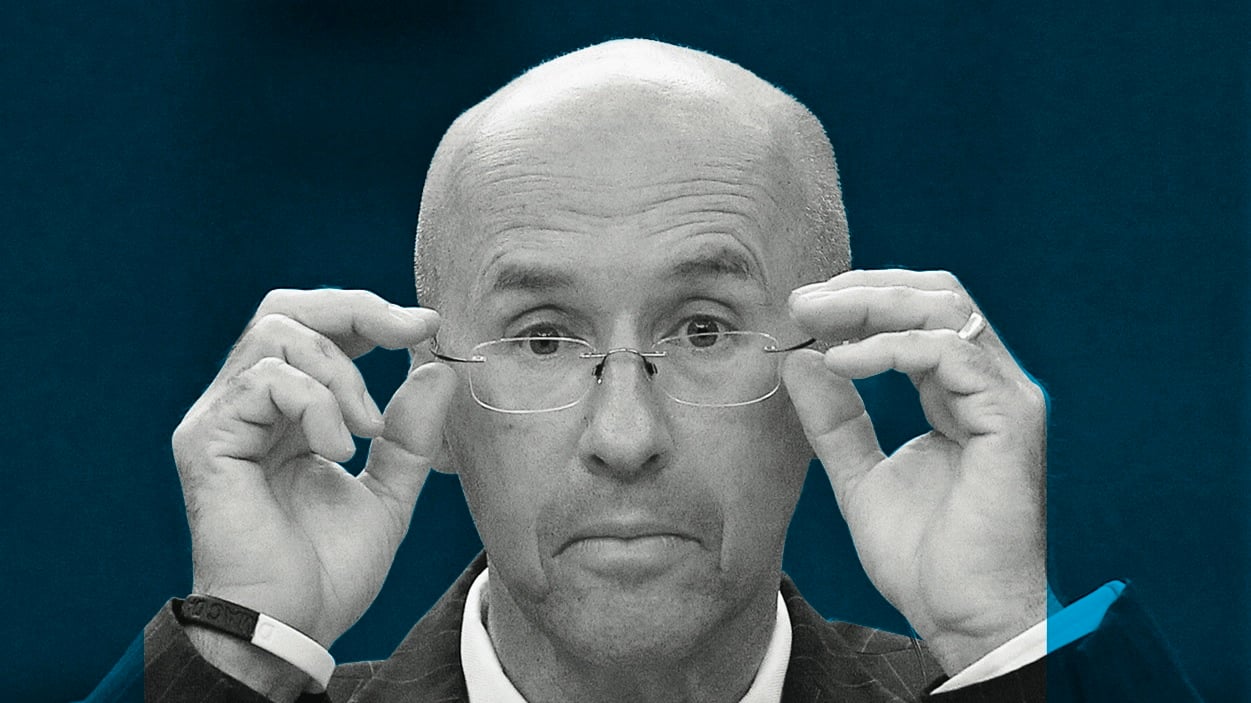

21: Kevin Page

21: Kevin Page

The badger

When Harper appointed the first-ever parliamentary budget officer—a new watchdog over federal spending and economic forecasting—the Prime Minister got far more than he bargained for. On paper, Kevin Page looked like a modestly successful bureaucrat, the sort unlikely to make waves.

As it turned out, Page has been a persistent, productively troublesome critic. (The accidental death of a son several years ago seemed to instill in him a determination to make a difference.) He’s questioned the government’s deficit numbers—and been proven largely right. He’s projected F-35 jet costs as far higher than the government claimed—and been backed up later by the auditor general. Through it all, his blue-collar, Thunder Bay, Ont.-bred ethos proved stubbornly impervious to Conservative ministers’ attempts to intimidate him into docility.

Although his five-year term as PBO wraps up at the end of this year, Page isn’t exiting quietly. He’s demanding details of budget cuts from dozens of government departments and agencies. Treasury Board President Tony Clement, Harper’s point man for the cuts, has slammed the budget officer for exceeding his mandate.

To the end of his term, Page is the embodiment of the power of independence under unrelenting pressure.

22: Justin Trudeau

22: Justin Trudeau

The social leader

Justin Trudeau has two voices. There’s the rather old-fashioned one that moved so many Canadians when he delivered the eulogy at the funeral of his famous father, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, in 2000. He reverts to that sort of grand oratory on big occasions, like when he launched his bid for the Liberal leadership back on Oct. 2. But there’s also the far less formal voice that his nearly 170,000 Twitter followers know so well through his frequent tweets on subjects ranging from where he’s headed for breakfast to what he thinks of the latest Conservative policy move.

No other Canadian politician approaches Trudeau’s mastery of social media. His massive following, and knack for the abbreviated form that holds their attention, is his sole indisputable accomplishment so far in public life. After all, he didn’t lead any organization before jumping into federal politics in 2008, and hasn’t landed a major critic’s role in the Liberal opposition caucus. It’s his social-media stardom that underpins his front-running bid for his party’s leadership.

Trudeau holds that the degree to which his party’s most dedicated young activists live their partisan lives in the digital arena is a direct reflection of their discontent with old-style politics. “I think of the rise of social media,” he told Maclean’s, “not as a root cause, but as a symptom.”

There’s no disputing the power Trudeau has tapped into. Still, experts who follow the politics of social media point to drawbacks and pitfalls. Brian Klunder, a Liberal official and public affairs consultant with Fleishman-Hillard, says Trudeau’s casual tweets established a valuable rapport with his followers over the past few years. But now the stakes are higher, the scrutiny more intense. And will voters be more inclined to see Trudeau as a lightweight because of his close identification with the Twitter throng?

These questions, however valid, don’t change the fact that any of Trudeau’s Liberal rivals, and Conservative and NDP adversaries, would pay dearly to duplicate his social-media success. There’s undeniable power in that instant access to an attentive online community. The political story of 2013 might well be the rise of Canada’s first social media-propelled pol to a federal party’s leadership.

23: Alex Himelfarb

The unofficial critic

As a bureaucrat, Alex Himelfarb spent half a lifetime faithfully executing politicians’ orders, a trajectory that peaked when he served as clerk of the Privy Council to Jean Chrétien, Paul Martin and, briefly, Stephen Harper.

Then came the surprise. Since he returned in 2008 from a stint as Canada’s ambassador to Rome, Himelfarb has become a leading public critic of Harper-style government, a blogging theorist of effective centre-left opposition.

His Alex’s Blog never mentions Harper by name, but it’s easy to tell he’s not a fan. A succession of Liberal leaders have kept Himelfarb on speed dial, but he enjoys not having a political boss anymore, and it’s the NDP that has most effectively borrowed his emphasis on income inequality as a winning issue for the left.

The government has other critics in the “greying establishment veteran” demographic —finance department retirees Scott Clark and Pete deVries, former Bank of Canada governor David Dodge—but it’s Himelfarb’s persistence and focus that make him a standard-bearer for Ottawa denizens who dream of a post-Harper Canada.

24: Stephen Woodworth

24: Stephen Woodworth

The rebel

For a few weeks this fall Stephen Woodworth was something of a maverick. With Motion 312, he called on Parliament to take up the question of when life begins, launching a discussion about abortion the Prime Minister has repeatedly expressed an unwillingness to engage. The debate thrust Woodworth into the spotlight: an illuminated place in which government backbenchers rarely find themselves. What’s more, the resulting vote, which saw his motion shot down, nevertheless exposed a split in cabinet. Ten members of cabinet supported him, most notably Jason Kenney and Public Works Minister Rona Ambrose, who also has responsibility for the status of women file. But Woodworth’s motion is just the most obvious in what have been several signs of life from the cheap seats on the government side. Though Tory David Wilks’s opposition to the year’s first omnibus budget bill was short-lived—and embarrassingly withdrawn—there have been other examples of a restive backbench. Mark Warawa followed Woodworth’s motion with a motion opposing sex-selective abortion. James Bezan recently acknowledged his opposition to the proposed takeover of Calgary’s Nexen by Chinese state-owned oil company CNOOC. And Brad Trost has mused vaguely of a proposal that would empower MPs. Yes, a healthy balance between party loyalty and MP independence is still a ways off. But the backbench can’t be ignored these days. Especially not with Woodworth emerging as the standard-bearer for the party’s largely quiet social conservatives.

25: Miriam Ziv

25: Miriam Ziv

The dogged envoy

Relations between Canada and Israel have rarely been as warm as they have become during Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s time in office. Canada consistently sides with Israel at the United Nations, and earlier this fall ended diplomatic relations with Israel’s arch-enemy, Iran. Israel, says Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister John Baird, “has no greater friend than Canada.”

Israel’s representative in Canada during much of this period has been long-time diplomat Miriam Ziv—though she downplays the role she’s had influencing Ottawa’s policy.

“There’s no doubt that I have ongoing and very good relationships with the ministers in the government. I can engage with them, talk with them, raise issues, and see how things can be done. And I find the doors open,” she says, noting that she has a particularly good relationship with John Baird but rarely talks to Stephen Harper. “But I must say the friendship is not dependent on a personality. I cannot attribute it all to myself. But I definitely hope that I have added onto this very special relationship that is based on shared values, on really understanding the fact that we are a democracy in a hostile, non-democratic region.”

Prior to her posting in Ottawa, Ziv served as assistant deputy minister for strategic affairs in Israel’s foreign ministry, where she focused on Iran and its perceived nuclear threat. This was a priority issue for her when she arrived and remains so—but in recent days it has been supplanted by the escalating violence between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

When not dealing with security threats, Ziv works to increase trade and other ties between Canada and Israel. It’s not an easy job, she says. She tries to convince to convince academic and business leaders to visit and see what opportunities may exist. “I’m out all the time. I’m in many ways tireless,” she says. “This is what my bodyguards tell me.”

Photos by Adrian Wyld/CP; Fred Lum/CP Images; Blair Gable; Andrew Tolson; Chris Wattie/Reuters; Blair Gable; Penny Bradfield/CHOGM/Getty Images; Sean Kilpatrick/CP Images; Ashley Fraser; Cynthia Munster; Todd Korol; Norm Betts/Bloomberg/Getty Images; Hill Times; Roger Lemoyne; Bruce MacRae/Flickr