The Nova Scotia shooting and the mistakes the RCMP may have made

New details about the Nova Scotia shooting are raising several troubling questions about the actions and response of the RCMP

RCMP officers stopped the killer at a gas station in Enfield, N.S. on April 19, 2020 (Tim Krochak/CP)

Share

This story was updated on May 14, 2020, to include a new comment from the RCMP

Previously unreported details about the Nova Scotia mass shooting last month are raising serious questions about the way the RCMP handled the nightmarish onslaught.

While Nova Scotians grieve their 22 dead, including an RCMP officer, they remain universally sympathetic to front-line officers still on the job. But law enforcement officers familiar with details that have not been made public are wondering aloud if at least some of the shooting deaths could have been prevented.

Here are six key questions:

1. Did the RCMP properly investigate reports that the killer assaulted his partner and had illegal guns?

The violence began when the killer, a 51-year-old denturist, went into a murderous rage after an argument with his common-law wife over a video call he made with a female friend, according to a police source briefed on the matter but not authorized to discuss it.

The killer—a heavy drinker with a history of violence and an obsession with the RCMP—was at a gathering with his partner at another home nearby in Portapique, a tiny seaside community 44 kilometres down the Bay of Fundy from the town of Truro in a sparsely populated coastal area of Nova Scotia.

They left after arguing about the call, but resolved the matter, at which point the killer’s common-law wife went to bed, the source briefed on the matter says.

He later woke her up, assaulted her, put one of her hands in cuffs, dragged her to a replica RCMP Ford Taurus, one of several replica police cars he kept. He shot at her twice to get her to move. He put her in the backseat of the vehicle, along with some containers of gasoline.

When he went back into the house, she slipped the cuff off her wrist and escaped from the car by sliding through the plexiglass divider between the front and back seats. She fled into the woods, where she hid until the morning.

Two sources briefed on the investigation believe that the killer may have been looking for her when he went to the home of Greg and Jamie Blair, who he murdered, apparently while their children, 10 and 12, were in the home.

Whether he had planned on the rampage or not, the killer appears to have prepared for one. He had replica RCMP vehicles and either an actual RCMP uniform or a convincing replica, which he wore as he went on his killing spree.

RCMP will eventually be asked to explain how the killer, who had a history of violence, managed to get hold of illegal guns, replica police cars and a uniform without raising red flags to the force, who had apparently been advised that he was a threat.

A former neighbour in Portapique told the RCMP that the killer, who she considered a “psychopath,” repeatedly assaulted his common-law-wife, who lived in fear of him. She told the RCMP that he had illegal guns, she told the Halifax Examiner and the Canadian Press.

The RCMP have said that the killer did not have a licence to own firearms, but used two semi-automatic handguns and two semi-automatic rifles in his murderous rampage.

Only one of the weapons was obtained in Canada, police say. They have not identified the weapons.

The neighbour, 62-year-old Canadian Forces veteran Brenda Forbes, has said that although three people witnessed one assault on his common-law wife, and she reported it to the RCMP, officers told her they could not act without the help of witnesses, who were unwilling to help.

Forbes believes the RCMP should have investigated the report of illegal guns.

“If you tell them that he may have illegal weapons, should you not go and check it out?” she said to the Canadian Press.

Forbes and her partner eventually left Portapique because of their fear of the killer.

The RCMP may already have had a file on the killer because of threats he made about 10 years ago, according to an interview his father did with Halifax’s Frank magazine. The killer’s father told Frank an officer went to Portapique to talk to him after he threatened to go to Moncton to kill his parents. His father also said his son beat him badly during a family trip to Cuba but they didn’t report it to authorities.

And in 2002, the killer pleaded guilty to a 2001 assault in Dartmouth. He received a sentence of nine months probation and a prohibition on owning firearms.

At a news conference on April 19, Chief Superintendent Chris Leather, the Criminal Operations Officer, appeared not to have been aware of the killer’s history of violence. Asked if the killer was known to police, Leather said “It’s early and I’m not aware of that.”

The RCMP said Thursday that they are not “looking into the gunman’s previous relationships and interactions,” but are not aware of the neighbour’s complaint: “As of right now, we have not found a record of this complaint being filed to the RCMP,” said Constable Hans Ouellette

2. Did the RCMP wait too long before entering the crime scene?

After the Blairs were murdered and the killer set their house on fire, their two children escaped to the home of neighbour Lisa McCully, a 49-year-old teacher of a combined Grade 3 and 4 class at Debert Elementary School.

McCully, a trilingual, fun-loving musician and loving mother, was murdered outside when she went to investigate, sources say.

The children are believed to have sheltered together in McCully’s basement and called 911, where they were connected with a civilian dispatcher at the RCMP’s Operational Communications Centre in Truro.

In all, the killer took 13 lives in Portapique, and set five buildings and several vehicles on fire.

In McCully’s obituary, her family thanks the RCMP and “the anonymous 911 person who stayed on the phone with [her children] for two hours.”

If that is accurate, police did not get to the children until an hour after the first officers arrived in Portapique. A source with knowledge of the events says the children stayed on the phone with the dispatcher during the 40-kilometre ambulance ride to the Colchester East Hants Health Centre, the regional hospital in Truro, which would have taken at least 30 minutes.

READ MORE: In memory of Emily Tuck, the young fiddler from Portapique

The timeline the RCMP released says that the force received a call at 10:01 p.m. and the first officer arrived in the community at 10:26. Spokespeople for the force in Halifax did not respond to repeated questions about how long it took before officers moved from the end of Portapique Beach Road to the burning houses.

It is not clear whether the killer continued murdering his neighbours while police were waiting at the end of the road, but some officers who were present have told others they waited too long.

“They were all set up on the end of the road and you could still hear gunshots and explosions in there,” said a source briefed on the matter. The source says some members eventually went up the road looking for the killer under their own initiative.

A 11:08 pm audio recording from an emergency medical personnel who was on the scene said “there’s a person down there with a gun. They’re still looking for him …. Police are stationed at the end of the road there on [Highway 2], not letting anybody down any further.”

Other sources briefed on events say they had not heard of a delay before officers went down the road and cautioned against concluding that police were wrong to hold back at the end of the road.

“Any time you have a shooter, and members who are willing to help, two minutes seems like forever. It’s OK to go in but it’s not OK to go in blind.”

The first car to arrive, likely a patrol car from the Bible Hill detachment, was coming to check out a shots-fired call, not an unusual call for RCMP officers in rural detachments. They did not know that they were about to enter a nightmare.

“The very first responding unit went in and it was a fucking disaster and they advised subsequent responding units,” said another source briefed on the events. “The very first car went in and there were multiple bodies. They pulled back. They had no fucking idea who or what or how many shooters. And they advised the responding units of the bodies, and that they were multiple, and that’s why they were collecting in force to do a containment and a proper approach.”

Police had to hold back emergency medical personnel and volunteer firefighters from nearby communities.

Meanwhile, four children were hiding in McCully’s home, talking to the dispatcher in Truro.

“There was communication between the members on scene, the telecommunications operator and the kids for them to stay fast, stay hidden, stay on the phone and that the police would come to them, and that they would be rescued, because that was the only living people that the police had any contact with at that point.”

When police eventually moved in, they did so cautiously, with their flashlights off so that they wouldn’t present easy targets to the killer. “It would almost be described as a war zone,” said a law enforcement source. “Fires. Gunshots everywhere. Miniature explosions, propane tanks in garages and in houses. It’s dark. The only light you’re going to get is whatever’s from the police cars and whatever’s from the burning houses.”

One source says officers believed they caught glimpses of the killer moving between houses as they proceeded.

“You’re alone. You’ve got bodies. You’ve got houses on fire. And you don’t know how many shooters there are.”

At 10:35 pm, the RCMP has said, the killer escaped the police perimetre by driving through a field, past the officers, in what would have appeared to be one of many RCMP Ford Tauruses on the scene.

“I’ve been in policing for almost 30 years now,” Superintendent Darren Campbell said later in a news conference. “And I can’t imagine a more horrific set of circumstances than searching for someone that looks like you.”

3. Why didn’t the RCMP issue an alert to warn the public?

After evading police, the killer drove north on unpaved back roads 30 kilometres to Debert, a farming community of 1,400, where he parked behind a welding shop for the night, while police set about the grim task of sorting through the carnage he had left behind in Portapique.

Police sources say that while the killer was resting in his replica vehicle, RCMP officers on the scene believed he was likely dead in one of the burning buildings.

The Canadian Press reported that a surviving gunshot victim told police that night that he was shot by someone in an RCMP vehicle, but there were three similar vehicles burning at the scene, so police wouldn’t have had reason to believe that the killer was still at large. They only learned that he was travelling around in a replica car when his common-law wife emerged from the woods the next morning around 6 a.m.

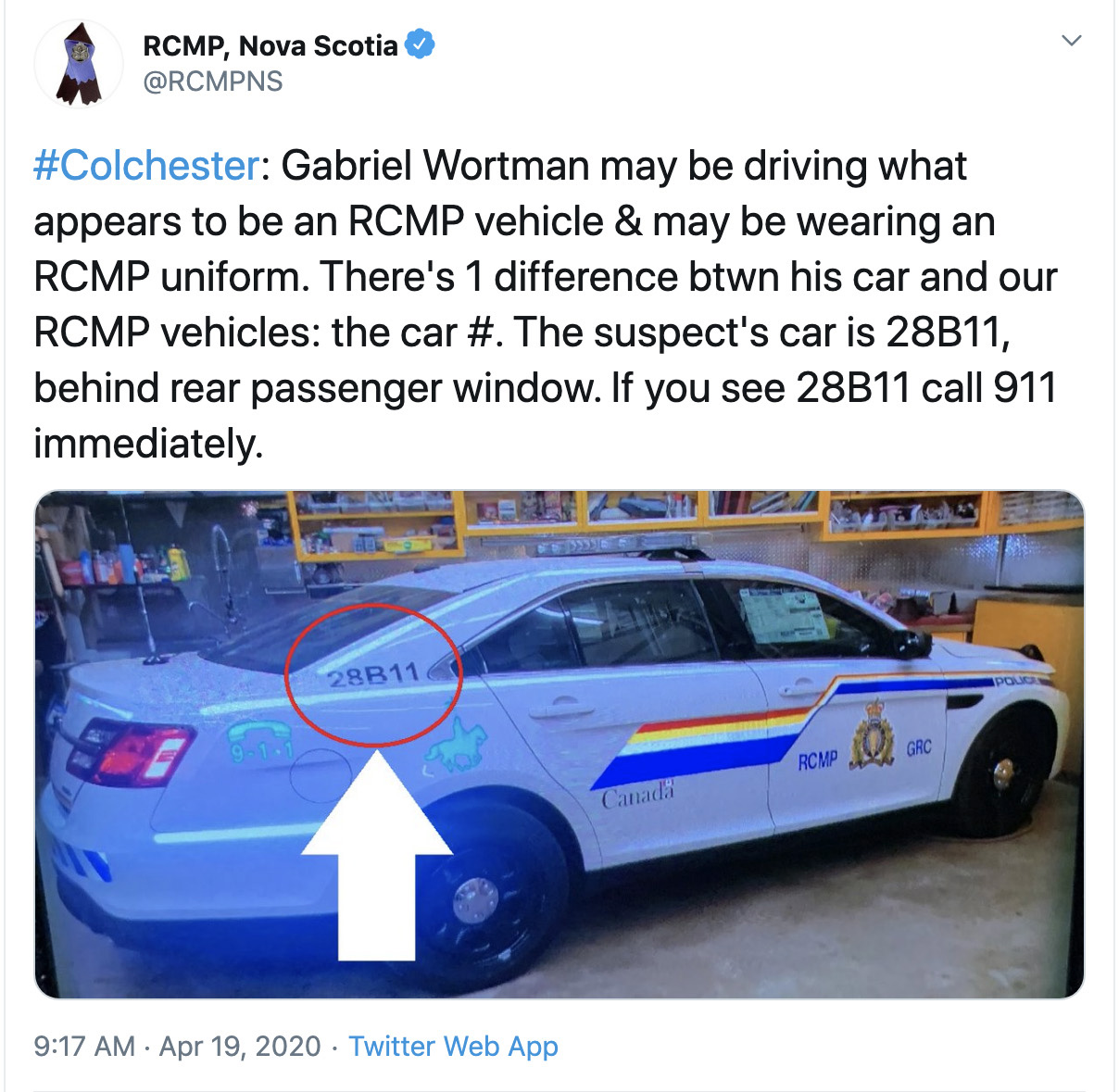

The woman, who was distraught after the assault and spending the night in the woods, told police about his weapons and the missing vehicle and gave them photos of the killer and his vehicle, which police distributed through Twitter, which is not the best way to reach rural Nova Scotians. The force sent several Tweets that morning, warning people to stay inside, but did not issue an emergency alert to cell phones, although the province’s Emergency Measures Organization asked them to do so.

While his common law wife was briefing the police, the killer was making his way to the residence of Alanna Jenkins, 37, and Sean McLeod, 44, corrections officers who lived in Wentworth, a small community home to a ski hill. He killed them and burnt their home. He also killed Tom Bagley, a volunteer firefighter, who came to investigate the fire.

It has been reported that police received a 911 call by 8 a.m that morning, which might have made them aware that the killer was continuing his murderous rampage. But they did not use the alert system to warn people to stay in their homes.

The system had never been used for an active-shooter warning, although it had been used in Nova Scotia days earlier for a COVID health warning.

At 9:35, the police received news that he had killed again, this time Lillian Hyslop, who was murdered as she walked beside the road in Wentworth, an apparently random attack.

Friends and neighbours believe an alert might have saved her life.

At 9:48 am, the killer visited the nearby home of a couple known to him, apparently planning to murder them, but they hid from him until he left.

At 10:08 am, police received a 911 call about the murders of Heather O’Brien, 55, mother of six, and Kristen Beaton, mother of a three-year-old son, who was pregnant with another child. Both were nurses with the Victorian Order of Nurses. The killer shot them in their cars in apparently random murders.

Nick Beaton, widower of Kristen, is still waiting for police to return her wedding rings and cell phone.

He is careful to say he doesn’t blame the “foot soldiers on the ground,” but believes the force’s failure to send an alert led to his wife’s death.

“The RCMP are as responsible for my wife and unborn baby’s death as much as that lowlife,” he said. “I can 100% guarantee with a warning my wife would be alive today. I can promise you that with every existence of my soul. She would not have went out the door.”

Police sources say the RCMP may have been afraid of sending an alert, in part because it could have put officers in jeopardy with armed members of the public looking to protect themselves, and also because their communications might have been paralyzed.

“We were chasing a guy in a police car and a uniform,” says a person familiar with the operation. “The number one thing I would be afraid of in putting out an alert is that we would be chasing our own shadows and depleting our own resources and eroding our containment because everyone would be calling in every police car they saw. That would be a tactical consideration.”

The officers running the operation were under terrible stress.

“People think these things are real time, like a CSI episode,” said the person briefed on events. “It doesn’t work like that. It’s a fucking shit show. We didn’t know where he was. We had no visual on him. We didn’t know where he was going to go.”

Other police sources think the RCMP made the wrong call.

“You say there’s an active shooter,” said a law-enforcement source who was not authorized to discuss the case. “If you’re home, stay home and lock your doors. You don’t have to say he was dressed as a Mountie or anything. People went about their lives and if one had been sent out, very likely they wouldn’t have done what they did.”

The RCMP has said they were preparing an alert when the killer was stopped. There had been speculation previously that they were waiting for approval from Ottawa, but knowledgeable sources say that is not the case, and operational decisions were all made in Nova Scotia.

At a news conference later, Chief Superintendent Leather said the force was “very satisfied” with its messaging through Twitter.

He said that police were preparing an alert when the killer was gunned down.

“So a lot of the delay was based on communications between the [provincial Emergency Measures Organization] and the various officers, and then a discussion about what the message, how it would be constructed and what it would say. And in that hour and a bit of consultation … is when the suspect was killed.”

In an interview with CBC Radio’s As It Happens, RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki acknowledged that it is possible that an alert would have saved lives.

“What I would say is that they did alert through Twitter, and going back to what I said earlier, you know, the more ways we can alert, the better.”

The force is now drafting a new policy on the use of alerts in active-shooter situations.

4. What happened at the Onslow Belmont Fire Hall?

At about 10:30 a.m, the chief and deputy chief of the Onslow Belmont Fire Brigade were in the fire hall, near Truro, setting up a muster point for evacuees from Portapique along with an official from Colchester County’s Emergency Management Organization.

While the men got the hall ready, an RCMP officer from Pictou County was outside, standing next to his cruiser, providing security.

Two other officers drove up and, believing the Pictou County officer was the suspect, opened fire on him.

“There was a horrible confusion for a nanosecond at the scene and the two officers who had stepped out at the car pointing firearms at this officer, discharged several rounds,” said someone briefed on the shooting. “They missed killing him.”

They apparently did not warn the Pictou County officer, as they would have been trained to do, and put dozens of bullets into the building.

“Didn’t challenge,” said another police source familiar with the details. “Didn’t speak. Just started opening fire. And [the officer] dove between the vehicles and started screaming on the radio to stop and they took off.”

The officers who opened fire did not speak to the volunteer firefighters before leaving.

Joy McCabe, who lives across the road, saw the beginning of the fire fight.

“And while I’m looking, that car pulled up right there in the middle of the road, opened both doors and started shooting,” she told the Truro Daily News.

Clair Peers, public relations officer for the fire brigade, says the firefighters inside hit the floor.

“They were immediately on the floor with the tables upturned and over, so they were shielded. They knew there was an officer out front to provide the protection they needed. But when somebody is shooting outside you don’t know what’s going on. So, they didn’t see anything that happened out there.”

The firefighters and the officer who came under fire are said to have been badly rattled by the experience, which is being investigated by Nova Scotia’s Serious Incident Response Team.

Peers said the RCMP officers involved can count on the continuing support of members of the fire brigade.

“We have every respect for what they do,” he said. “We meet them at accident scenes and all sorts of situations. So we just expect the best thing that can be done will be done. We want to give them every assurance that they have our confidence and we respect what they’re doing.”

5. Why didn’t the RCMP use other police forces to keep the killer from travelling?

While RCMP officers were shooting up the fire hall, unbeknownst to police, the killer was driving around in his replica cruiser through the downtown business district of Truro.

Police have not said why he went there. There is no indication he attempted to gain entry to the hospital where his common-law wife and other shooting victims were being treated.

Truro Police were notified of the shooting when they were asked to assist with a lockdown at the hospital at midnight on April 18. They put extra officers on the next morning and contacted the RCMP to offer assistance but “the RCMP thanked us for our offer but did not ask for assistance,” said spokeswoman Josee Gallant.

It is not clear why the RCMP didn’t ask the Truro and Amherst police to set up roadblocks to prevent the killer from leaving the area. Roadblocks at the entrances to Highway 102, which leads to the killer’s Dartmouth home, could easily have been blocked by Truro police, closing a natural chokepoint where the Bay of Fundy divides the province.

“The Truro Police cannot comment on what the RCMP did or did not do,” said Gallant. “The Truro police was not asked to set up roadblocks or a perimetre for containment.”

The Truro Police only became aware that the killer had driven through Truro “when the RCMP released the video showing the vehicle driving through town [approximately a week later].”

The Amherst Police Department stepped up to backfill for a nearby RCMP detachment, but otherwise received detailed information only through back channels with local Mounties who have a good working relationship with Amherst police officers.

“I see no indication that they engaged Truro police or Amherst police, who are on either side of that, who have 60 sworn officers between them,” says Paul Palango, a retired journalist who wrote three highly regarded books on the RCMP and now lives in Nova Scotia. “But they did call in RCMP resources from New Brunswick, which is an hour and half away, and God knows when they got there.”

Surveillance video shows the killer stopped to remove his jacket and put on a yellow traffic vest at Millbrook First Nation, outside Truro, before heading toward Dartmouth.

Twelve hours after he began his rampage, he was still at large, having eluded his pursuers. Nineteen people were dead. Three more were to die.

“Why weren’t roads flooded by police?” says Palango. “Why weren’t they stopping everyone? Why wasn’t the province shut down? There’s not that many roads.”

6. Why wasn’t Heidi Stevenson’s cruiser equipped with a push bar?

After the killer left Millbrook, his next victim was Constable Chad Morrison, who was waiting for Constable Heidi Stevenson, a mother of two and 23-year veteran officer, at a highway junction in Shubenacadie at 10:45 am when the killer drove up next to him and shot him.

“Const. Morrison thought that the vehicle was Constable Stevenson. The approaching police vehicle was actually driven by the gunman,” Superintendent Darren Campbell said at a news conference.

Morrison managed to drive away and radio for help. Stevenson, who was nearby, tried to stop the killer. They collided head on. The killer shot and killed Stevenson and took her sidearm.

The vehicle that Stevenson was driving was not equipped with a push bar on its front bumper, unlike the replica vehicle that the killer was driving, which may have given him an advantage in the collision, according to some experts.

Palango points out something similar happened in 2006 in Spritwood, Sask., when RCMP constables Robin Cameron and Marc Bourdages rammed a vehicle being driven by a man wanted for domestic assault. Their airbags deployed and while the officers were trapped, the suspect managed to kill them both.

Some, but not all, police forces use push bars. Palango thinks that may have been one factor that led to the tragic death of Stevenson.

“RCMP would not address this issue,” says Palango. “So they still have no push bars on their cars in Nova Scotia.”

One police source says Stevenson’s airbag did not deploy, so the replica vehicle’s light, aluminum push bar does not appear to have been decisive. But if her vehicle had been equipped with a heavy steel bar, the exchange could have ended differently.

After shooting Stevenson, the killer set the vehicles ablaze and killed Joey Webber, a 36-year-old father of two who stopped to help. The killer stole Webber’s car and drove it to the nearby home of Gina Goulet, who he knew, murdered her, changed into civilian clothes and stole her car, which was low on gas.

At the Irving Big Stop in nearby Enfield, two RCMP officers — one from a Emergency Response Team and a canine officer — recognized the killer from the photo they had seen on their phones while he was filling his stolen car. They warned him and, when he failed to comply with their warnings, repeatedly shot him. He died after they put the cuffs on him, a source says.

The RCMP in Nova Scotia is reeling from the incident. Members who know and loved Stevenson are turning up to work every day, holding their emotions in check so they can keep doing their jobs. A number of members of the force have been unable to return to work and many more are likely to have long-term challenges dealing with the trauma of the crime scenes.

Some of the Mounties who pursued the Portapique killer are still dealing with trauma from the 2014 Moncton shooting, which took the lives of three Mounties.

After that tragedy, the force was found guilty of labour code violations and fined $550,000 for failing to provide its officers with adequate training and equipment, in particular, high-powered rifles.

The force had failed to properly equip its officers in spite of the recommendation of an inquiry into the 2005 shooting death of four outgunned RCMP officers in Mayerthorpe, Alta.

The RCMP is continuing its investigation. It has conducted 500 interviews and searched 17 crime scenes. The Serious Incident Response Team is investigating both the fire hall shooting and the death of the killer. The Nova Scotia Medical Examiner is investigating the deaths.

Beaton, who has lost his wife and unborn child, has launched a class action lawsuit seeking a public inquiry into the murder rampage, the worst mass shooting in Canadian history.

Observers expect the province will eventually call a public inquiry into the affair under Nova Scotia’s Public Inquiries Act, although it is also possible that a joint federal-provincial inquiry will be held instead.

“It is premature to consider a public inquiry at this time,” said a spokesperson for Nova Scotia Justice Minister Mark Furey. Furey is a former member of the RCMP.

Stephen Maher can be reached at [email protected]