An MS trial reported ‘definitive’ results before it was done. Why?

Results from a key Canadian study into venoplasty for MS appear to have been prematurely released, leaving questions

Dr. Daniel Simon points to the dye running through the jugular vein of Neelima Raval, 38, who has lived with multiple sclerosis for 13 years, and who is being tested for narrowed veins by Dr. Simon at the John F. Kennedy Medical Center in Edison, N.J., June, 8, 2010. Dr. Paolo Zamboni, a vascular surgeon from Italy, believes that the disease, which damages the nervous system, may be caused by narrowed veins in the neck and chest that block the drainage of blood from the brain, and has reported in medical journals that opening those veins with the kind of balloons used to treat blocked heart arteries can relieve symptoms. (Beatrice de Gea/The New York Times)

Share

On March 8, 2017, findings from a Canadian-government-funded clinical trial looking into a treatment for a vascular condition associated with MS were rolled out with carefully orchestrated fanfare. The tone was set by a press release issued by the University of British Columbia and Vancouver Coastal Health Research: “Controversial ‘liberation therapy’ fails to treat multiple sclerosis,” the headline read. The study, the release said, provides “the most definitive debunking of the claim that patients could achieve dramatic health improvements from a one-time medical procedure.” Lindsay Machan, a UBC associate professor of radiology and one of the study’s investigators is quoted: “We were committed to meticulously evaluating this treatment with robust methods and patient-focused outcomes.”

Reading the announcement, one would conclude the tortuous and contentious eight-year quest for research into the benefits of venous angioplasty for people with MS had come to an end. It proclaimed a “debunking,” a word that bristles with non-scientific ridicule and agenda. Declaration of “definitive” research also lacked scientific curiosity; science advances by proving science wrong. Talk of “meticulous evaluation” raised questions as well: Clinicaltrials.gov lists the UBC-Vancouver Coastal Health-led $5.4-million trial as still “active,” with an “estimated completion date” as September 2017. No one expected to hear from the researchers for months. Yet there they were with 48-week data—a short timeline, as anyone familiar with research into a condition as variable as MS knows. What was going on?

Questions mounted throughout the day. Machan presented “Week 48 results” before the Society of Interventional Radiologists (SIR) annual meeting in Washington, D.C. There was no abstract, no poster, no peer-reviewed study of the sort associated with new scientific research. Instead, 33 slides relayed that 49 subjects had been treated with venoplasty and 55 with a “sham” (the surgical equivalent of placebo). The researchers found no difference in benefits, as reported by the patients or determined by physicians.

North of the border, the clinical trial’s director, Anthony Traboulsee, went on a one-day media blitz. Traboulsee, an MS neurologist and director of the MS Clinic at the Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health at UBC, has produced other research “debunking” a theory put forward by Italian venous specialist Paolo Zamboni who hypothesized blocked veins impeding blood flow was common in people with MS; he classified these patterns as “cerebrospinal venous insufficiency,” or CCSVI. Zamboni’s small 65-person observational study concluded venous angioplasty improved or even eliminated MS symptoms; it called for further randomized controlled clinical trials. CCSVI has been the subject of international research producing conflicting results ever since.

Now, here was Traboulsee saying that CCSVI has been conclusively studied; it was time to move on. “I don’t see any benefits to people pursuing this treatment after the results of our study,” he told the CBC last week. The file on CCSVI should be closed, he told CTV News: “It’s done.”

The gleeful “debunked” message was echoed in media. The CBC ran with: “‘Scientific quackery’: UBC study says it’s debunked controversial MS procedure.” Multiple Sclerosis News Today proclaimed “So-Called ‘Liberation Therapy’ for MS is Useless, Costly and Potentially Dangerous, Study Finds,” though the findings suggested no risk and did not mention costs.

The announcement of “definitive” trial results surprised no one more than Geoff McNeill, one of the trial’s 104 participants. The 47-year-old, who lives in Langley, B.C., was blindsided by the newspaper stories, he told Maclean’s. He has a follow-up assessment scheduled for May, a seven-hour battery of tests and an MRI. “I am one of the 104,” he says. “Why isn’t my experience included?”

He’d committed more than 30 hours to the trial, not counting the 90-minute drive back and forth from his house to UBC. He reports a positive and marked difference between two interventions. Yet, in a trial focused on “patient-focused outcomes,” his experience after his second procedure had not been studied.

McNeill, a chartered shipbroker, joined the trial in 2015 inspired by his wife, Caroline, who was diagnosed with MS in 2006. She was one of the tens of thousands of Canadians who travelled out of the country, against the advice of MS neurologists, when the treatment was not made available in Canada (venoplasty is covered for other conditions under provincial health plans).

The exodus put a spotlight on a patient population eager for new approaches—and frustrated with the MS status quo. More than 100,000 Canadians and 2.5 million worldwide have been diagnosed with MS, a condition that has confounded medicine for a century and a half. It often strikes young, between 15 and 40, and is three times more common in women. MS is unpredictable; over time, it can render people blind and paralyzed, or it may not. There is no known cause, cure or definitive test.

Anecdotal reports of CCSVI treatment varied. (It was dubbed “liberation therapy” by staff at Zamboni’s hospital in Italy and later the media.) Quickly it was evident it was not a “cure.” Some saw significant improvements, while others experienced improvements that dwindled; others felt no change. Adverse effects post-treatment were reported, some of them dire. Two Canadians died with post-operative complications, one man after being denied aftercare in Canada.

Caroline McNeill’s experience, though, was positive: a surge in energy, which abated in time. She returned to New York state for a second treatment; the results were not as pronounced. She travelled again, to California, where a blockage was cleared and she felt marked improvements. Then, in 2011, Geoff was diagnosed with MS. He considered traveling for CCSVI treatment but couldn’t afford it at the time. But he was excited when he was accepted in 2015 for the Canadian clinical trial.

McNeill says he was surprised when he learned Traboulsee, his neurologist, was leading the the study, given how dismissive he had been of CCSVI both publicly and personally. Still, he was hopeful, not only because the treatment might offer symptom relief, but also because he wanted to contribute to the science. In June 2015, he underwent the first intervention, not knowing whether it was venoplasty or a sham, per the trial’s “blinding.” He felt no different. In May 2016, he had “crossover” treatment (those who’d received “sham” underwent venoplasty and vice versa). After that, he could run up the stairs for the first time in years. He was able to return to the slopes with his two children. Over the next months, some benefits abated (he says he can no longer could run up stairs, but he skis).

Maclean’s interviewed Traboulsee last week during his media rounds. After hearing McNeill’s story after that interview, Maclean’s contacted UBC to share McNeill’s concern and to ask about the status of its data collection. The “clinical trial and patient evaluation is continuing,” a UBC spokesman, speaking on behalf of Traboulsee and Maclan, said in an email. He said that patients had been informed 48-week results would be released (McNeill says he hadn’t been told). Not all data was in, the UBC spokesman said: “post-crossover data of all participants are still being collected and they are continuing to be monitored….Those results will be included in the final data set.” Maclean’s second query asking why results had been announced as “definitive” when data analysis was incomplete, sent to both UBC and Traboulsee, remains unanswered. (This post will be updated if and when it is.)

Release of clinical trial results before the database is officially closed is unusual, one expert in clinical trial design told Maclean’s. Unable to review the UBC trial protocol, he asked his name not be used. Maclean’s request for the protocol from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the primary funder—the MS Society of Canada, and the provinces of British Columbia, Manitoba and Quebec also provided funding—was redirected to UBC, who did not supply it.

Data is released early under a few circumstances, the expert says: “One, the results of an ‘unblinded’ futility analysis concludes that with the data available there is no significant effect; and, two, the Medical Safety Review Board concludes the incidence of adverse and serious adverse events outweigh the possible benefits. If there was an independent ‘unblinded’ board which was reviewing data real time and the statistician concluded ‘futility,’ then the trial could be stopped—but that does not appear to be what happened in this trial.”

Why UBC released the data early is unclear. Doing so succeeds in getting their preliminary data out before two other CCSVI clinical trials report. One, in Australia, is ongoing. The second, a 360-person Italian trial which commenced in 2012 is expected to report in mid-2017, after it is peer-viewed and published, Zamboni reported in November. UBC researchers submitted their presentation to the SIR meeting after that announcement, and the meeting’s Sept. 30 submission deadline. It’s not unprecedented to share early results, Traboulsee told Maclean’s. “We debated that. We had an obligation to get the results out in a timely manner.”

The SIR meeting was chosen because interventional radiologists (IRs) are interested in the procedure, Traboulsee says. Yet that presentation didn’t focus on measurements used by interventional radiology—blood flow, venous pressure, size of stenosis, restenosis rates. That concerned Salvatore Sclafani, a Brooklyn, NY-based IR who attended the meeting. Without such before-after data, it’s impossible to know whether the trial properly treated CCSVI, he told Maclean’s.

CCSVI treatment has evolved markedly since 2009, says Sclafani, who has performed hundreds of procedures. Nothing he saw at the meeting would cause him to change his protocol or willingness to treat, he said. “The study was focused on proving Zamboni’s early study right or wrong,” he says. “We need to see the paper.”

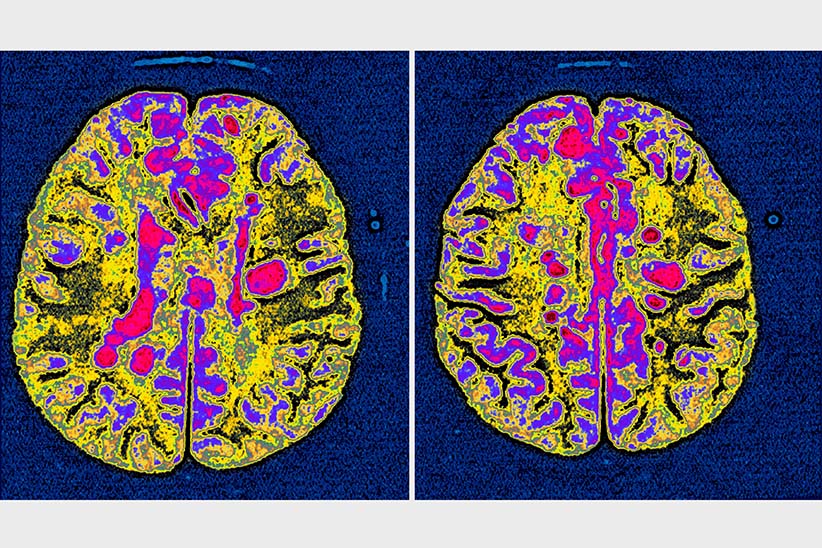

The declaration that CCSVI research is “done” leaves unanswered why many people with MS reported symptom improvements that have been lasting, some quantifiable. One high-profile example is Jeff Beal, North America’s CCSVI Patient Zero who talked about his experience at the Sundance Film Festival last month. The Los-Angeles-based composer known for his work in film, TV and symphony, was treated at Stanford Medical Centre in 2009; he had returned for retreatment. Beal’s energy, cognition and sleep patterns improved markedly after, accompanied by a new diet and exercise regimen. Some improvements were measurable: reversal of gray matter atrophy on MRI, a doubling of jugular vein blood volume, no new MS lesions, and shrinkage of older ones.

Burnaby, B.C. resident Lori Batchelor also experienced enduring improvements; she provided Maclean’s with medical records from her UBC neurologist, John Hooge, now retired. Batchelor had secondary progressive MS when she traveled to the US in March 2011. Her EDSS (a 0-to-10 MS disability scale in which 10 is “death due to MS”) rose from 2 in 1993 to 6.5 in 1998; in 2013, after treatment, it improved to 4, where it has remained. A March 8, 2012 note from Hooge to Batchelor’s GP read in part: “Lori is better than she was a year ago. She is walking better and her right leg is stronger. This appears to have occurred following the procedure for CCSVI.”

Senator Jane Cordy, who introduced a Senate bill in 2011 calling for accelerated research into CCSVI, was inspired to do so after hearing dozens of stories firsthand, she says. “One woman went from bedridden to presenting at a CCSVI meeting on the Hill,” she says. Another left nursing-home care and was self-reliant. “Nobody sees the treatment as a miracle cure,” says Cordy. “But people with MS need options.”

Currently those options focus only on MS drugs, a $21.5-billion industry based on the theory MS is triggered by the immune system attacking itself. They’re sold with the promise of reducing relapses and delaying disease progression. Many come with brutal side effects, including death risk. No drugs have yet been developed for those with progressive forms of MS.

Traboulsee highlighted the benefits of MS medications in last week’s press release announcing the “debunking” of CCSVI: “Fortunately, there are a range of drug treatments for MS that have been proven, through rigorous studies, to be safe and effective at slowing the disease progression,” he is quoted saying. Like many MS neurologists, Traboulsee works actively with industry in new drug development. (Recently he has been a spokesman for the MS drug Lemtrada and also is running a tranche of an international clinical trial for the Genentech/Roche drug ocrelizumab (Ocrevus) which he has praised publicly.)

Such relationships don’t represent financial conflicts of interest or compromise his objectivity, Traboulsee told Maclean’s last week. The trial’s design had “layers of protections built in to avoid bias,” he says, including an independent data monitoring board, independent trial monitors, and a data-locking process before data was sent to statistician. “We weren’t out to beat [CCSVI] up.”

When the limitations of MS drugs was pointed out to him by Maclean’s, Traboulsee agreed, in part. “Unfortunately those drugs are not reversing the disability and improving symptoms,” he says. “What the ‘liberation therapy’ has brought to light is that is the need.”

Reports of improvement after CCSVI treatment are a conundrum, says Traboulsee: “We all struggle to understand the full reason people get better.” It could stem from the variability of the condition or “placebo effect,” he suggests. His group looked at who might benefit, with no luck. “We tried to look at all the baseline features—if you had relapsing remitting MS, if you were a woman, a certain age, if you had enhancing lesions on your MRI—could any of these factors predict a better outcome?” Asked if it should be an area of further research, he prevaricates: “The fact that people get better, I’d love to know why they get better so we can tap into that and help more people get better.”

The proclamation CCSVI “is done” ignores a new vanguard of research outside of MS neurology committed to investigating the link between neuro-degenerative diseases, blood flow, and the vascular system. The discovery of a brain lymphatic system in 2015, for example, stands to revolutionize understanding of the brain, and hopefully provide new insights into diseases like MS, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

CCSVI, enshrined medically in a chapter in the 2016 edition of the Oxford Textbook of Vascular Surgery, is also being associated with other disorders. A study presented at the SIR meeting found high incidence (89 percent) of CCSVI in people diagnosed with Meniere’s disease, an incurable degenerative inner ear disorder whose symptoms include intense nausea and dizziness, vertigo and tinnitus. Like MS, its aetiology is unknown and has been linked to viral infection and autoimmune reaction. Venous angioplasty, the study found, reduced Meniere’s symptom severity.

A few MS neurologists remain curious. Alireza Minagar, who teaches at Louisiana State University, told CTV News he believed further research is needed. CCSVI is in its “infancy,” he said. Like Zamboni, he calls for “collaborative” multidisciplinary research into MS and other neurodegenerative diseases.

McNeill expresses concern the results released last week will have a tamping effect. “Please don’t let this be the end of Canada’s investigation into CCSVI,” he says. Signs of shutdown are evident. The day preliminary clinical trial results were released, the CIHR and MS Society of Canada announced the “working group” created in 2011 to study CCSVI had been wound down the previous day. The same afternoon the FDA issued a warning on venous angioplasty being used for autonomic disorders, including MS.

“I’m not a militant MS’er for CCSVI,” says McNeill. “But I believe there is something to it. I witnessed it with my wife and I experienced it,” he says, though he does not know which procedure occasioned his improvement. “Whether it’s a combination of factors or a piece of a puzzle, I don’t know.” He will honour his commitment to complete the trial, he says. “What they do with my data, well, I guess I have to hope for the best.”

Last week, Traboulsee sounded conclusive. “It would have been great if we had something new we could have offered patients,” he told Maclean’s. “And we will have something new to offer patients. I just don’t think this is it.” It’s a telling remark, reflecting the traditional doctors’ perspective of dispensing medicines. Yet it also exists at disconnect from the new reality: a patient population with a devastating disease using social media to share medical experiences and advocate for new avenues of inquiry. The release of “definitive” and “debunking” results from a clinical trial still ongoing is only destined to widen the chasm between the two.