The colonial history behind B.C. Day that can make us all proud

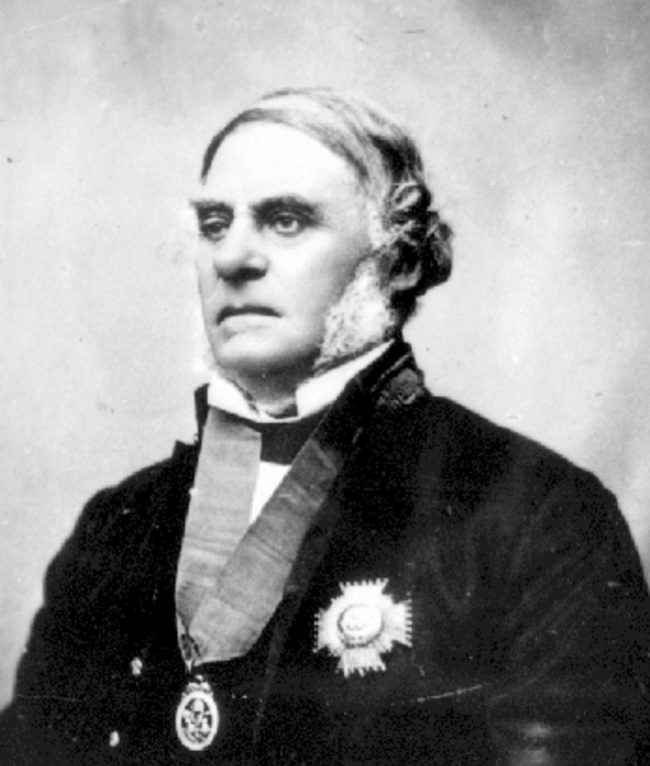

A colonial governor who was part black welcomed racial minorities and stood up for Indigenous people against marauding Americans: How was he airbrushed from the modern narrative?

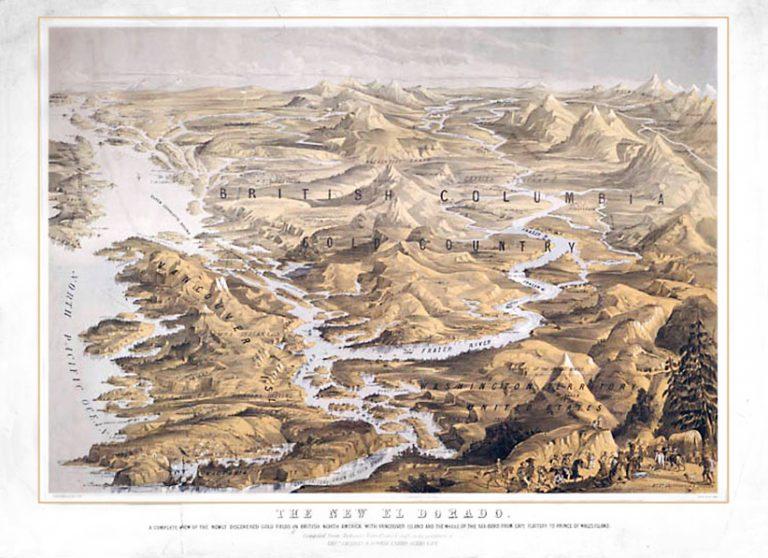

B.C. was viewed as the “New El Dorado” by gold-seeking Americans who flooded the colony, prompting Governor James Douglas to assert the Crown’s authority

(Library and Archives Canada/Wikimedia)

Share

It’s not just the passage of time that explains it. No matter how dramatic, some crucial events of history defy the convenient meta-narratives that nations devise for themselves, and so they’re forgotten. That’s just one reason the bloody catastrophe that unfolded in the summer months of 1858, in what is now British Columbia, is unknown to most Canadians.

There was an American invasion, a war that claimed perhaps hundreds of lives, and a shaky truce that eventually invited the breadth of Canada to extend from Atlantic to Pacific. That should count for some special place in Canada’s collective memory, you might think.

But what gets in the way of remembering what happened that summer involves the way we tend to profess our shame about the country’s past, or alternatively congratulate ourselves about our conquest of the wilderness, or fancy ourselves to be superior to the racist scoundrels who came before us. The horrific and heroic events of that summer 160 years ago simply can’t be made to sit still for such self-portraits. So the whole drama has been strangely airbrushed from history, along with the existence of a courageous little colonial world that ended up wholly undone by the terrible events of that same year.

The Fraser Canyon War, as it came to be called, was “a conflict of cataclysmic proportions,” the historian Daniel Marshall explained to me the other day, “and it’s also one of the greatest untold stories of our time.” Author of the just-published book Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New Eldorado (Ronsdale Press), Marshall reckons that right about now, the first week of August, 160 years later, would be as good a time as any to remember the story.

RELATED: Justin Trudeau was right to exonerate the Tsilhqot’in, who never were defeated

The first Monday in August is British Columbia Day, a holiday that recalls the Westminster Parliament’s proclamation of the Crown Colony of British Columbia on August 2, 1858. The proclamation itself was a direct response to the uproar set off by the discovery of immense gold deposits in the Fraser Canyon, a frenzy that led to that summer’s invasion by at least 30,000 American miners who immediately organized themselves into several heavily-armed militias to make war on the Fraser Canyon’s Indigenous people.

Another difficulty is that the Fraser Canyon War doesn’t align with the conventional telling of Canadian history as an east-to-west epic. British Columbia’s story runs on a north-south axis, with a forward view out on the Pacific rather than a backward view across the Atlantic. On the Pacific coast, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s trade in tierces and hogsheads of salmon had always been far and away more voluminous and profitable than trade in furs. A third of the HBC’s workers on the Pacific side of the Rockies were Hawaiians. The handful of treaties concluded on Vancouver Island in the early 1850s took no Canadian treaty as a model, but instead replicated the Treaty of Waitangi between the British Crown and New Zealand’s Maoris.

The first significant wave of settlers to arrive on the Pacific coast north of the 49th parallel did not come from the East. They were the vanguard of a northward-bound exodus of “King George men” from the HBC settlements on the Columbia River, in what is now the state of Oregon. Dispossessed by American interests under the terms of the Anglo-American Oregon Treaty of 1846, and led by the HBC veteran James Douglas, they were mainly Indigenous people, Orkney Islanders, Hawaiians, Metis and Scots. They were welcomed on Vancouver Island by the Saanich and Songhees tribes among whom they first settled. In London, Douglas was appointed Vancouver Island’s colonial governor.

Meanwhile, backed by the U.S. Army, American miners poured into the old Oregon territory that Douglas and his people had been forced to vacate, and the result was carnage. There was the Cayuse War, the Nisqually War, the Yakima War and the Klamath and Salmon River War. By the early months of 1858, word had spread from California to New York that the Fraser and Thompson canyons were glistening with gold, and the miners began pouring north into what was then the HBC district of New Caledonia, the unceded territories of several confident, populous indigenous tribes.

The fighting in the Fraser Canyon was merciless. The miners burned villages and shot women and children. The Nlaka’pamux fought back, sending headless corpses down the river. As the HBC’s senior officer on the Pacific, and Vancouver Island’s colonial governor, Douglas was the British Crown’s senior figure in the conflict, and he refused American entreaties to take their side against the tribes. Instead, he assured the Indigenous leadership that the Crown would take pains to defend their rights as British subjects.

Douglas did his best to assert Crown sovereignty on the mainland, but it was usually by bluff. Resistance to the American hostilities fell mainly to the Fraser’s Indigenous people. While the Nlaka’pamux were joined by Secwepemc, Okanagan and other allies, a repeat of the genocidal terror that had become so routine south of the 49th parallel was only narrowly averted in the Fraser Canyon. It was only when Nlaka’pamux war chief Sexpinlhemx agreed to pleas for peace put forward by an unusually sensible Californian militia leader, “Captain” H.M. Snyder of the so-called Pike Guards, that the immediate crisis passed.

A good thing, too. There were 1,500 U.S. soldiers ready to move in from the American side of the border if events turned against the miners. Had matters come to that, it’s unlikely that anything would have become of the Crown Colony of British Columbia, and there would have been no Province of British Columbia in 1871, and no eventual Canadian presence at all on North America’s Pacific coast.

Another aspect of the story that has caused it all to be largely forgotten is that nothing about it conforms with the reactionary view of shiftless, indolent Indians that only British discipline could redeem. The Nlaka’pamux and their neighbours were B.C.’s first gold miners, immediately alert to the value of the metal at HBC forts. They and their neighbours were astute entrepreneurs and reliable partners with the HBC in the utilization of New Caledonia’s resources.

RELATED: How a smallpox epidemic forged modern British Columbia

Neither does the role of the Crown, nor the brief life of the Colony of Vancouver Island, comport with the fashionably dreary conception of a “racist colonial settler state.” From the time of its establishment in 1849 to its merger with the mainland colony to form the united Colony of British Columbia on August 6, 1866, Vancouver Island presents a radical “counter-narrative” of its own.

Oregon’s first American government passed a law in 1848 prohibiting any “negro or mullatto” from taking up residence in the territory. California adopted laws forcing Chinese people to leave the state. African-Americans were hounded out the towns and the mining districts. They were denied the vote. Their testimony was inadmissible in the courts.

Governor Douglas himself was an “octoroon,” in the racial classifications of the time—his grandmother was a “free coloured woman” from British Guiana. His wife Amelia was an Irish Cree. Douglas invited Chinese immigrants to leave California and come to Vancouver Island—Victoria’s Chinatown flourishes to this day. In 1858, the year of the Fraser Canyon War, Douglas met with a delegation of African Americans from California and invited them to bring their friends and families to settle on Vancouver Island, too. In 1858, the year of the Fraser Canyon War, more than 700 African-Americans arrived in Victoria.

By 1861—the first year of the American civil war—American miners arriving by ship in Victoria harbour were greeted by the African Rifles, a regiment of Black men, armed, in uniform. Among Victoria’s first African-American settlers was Mifflin Gibbs, the celebrated African-American anti-slavery campaigner. Gibbs went on to serve as an elected city councillor under Lumley Franklin, British North America’s first Jewish mayor. Victoria’s Congregation Emmanu-El synagogue, built in 1863 in the Romanesque Revival style, is still standing.

RELATED: B.C. apologizes for past policies towards Chinese Canadians

Governor Douglas also adopted a standpoint on aboriginal rights and title that was radically liberal compared to the Canadian federal Indian Act system. He negotiated 14 treaties on Vancouver Island – the only treaties West of the Rockies until the Nisga’a agreement of 2000. Denied further funds from the Colonial Office in London, Douglas directed surveyors to lay out British Columbia’s first reserves to include all occupied village sites and farm fields, “and as much land in the vicinity of each as they could till, or was required for their support.” Douglas further instructed that Indigenous people should be allowed to “freely exercise and enjoy the rights of fishing the Lakes and Rivers, and of hunting over all unoccupied Crown Lands in the Colony,” and should be permitted to “dig and search for gold, and hold mining claims on the same terms precisely as other miners.”

The point, Douglas said, was to ensure that Indigenous people were “conscious that they were recognized members of the Commonwealth.” There was only one significant intrusion on Indigenous customs that Douglas insisted upon: the abolition of slavery.

In 1871, the year British Columbia joined Confederation, Victoria voters elected Henry Nathan—Canada’s first Jewish Member of Parliament. But by then, the liberal, multicultural regime Douglas had overseen was already withering away. The Chilcotin War of 1864 erupted only weeks after Douglas retired. Several of the larger Indian reserves Douglas authorized ended up severely reduced in size. The British Columbia legislature went on to adopt racist laws that would have been unthinkable in Douglas’s time.

The story of 1858 and the colonial milieu of the time bears remembering, though, perhaps most usefully as a humbling reminder. In all our strenuous efforts to be impeccably diverse and multicultural and mindful of the value of “reconciliation” between this country’s settler and Indigenous communities, we are not necessarily breaking new ground. We have traditions to draw from, and to be proud of.

“This whole country needs a deeply inclusive story that all of us can see ourselves in,” is the case Claiming the Land author Daniel Marshall makes.

Most Canadian provinces have a civic holiday on the first weekend in August, and British Columbia Day isn’t really a new thing, even though it was officially proclaimed as a provincial statutory holiday only in 1974. In the 1860s, B.C.’s August civic holiday, usually observed on August 1, was to celebrate the outlawing of slavery in the British Empire.

That, too, is worth remembering.