Canada’s oldest person: Living through 112 years of history

Dolly Gibb is only 38 years younger than Canada. Tracking her life allows us to follow the growth of a nation.

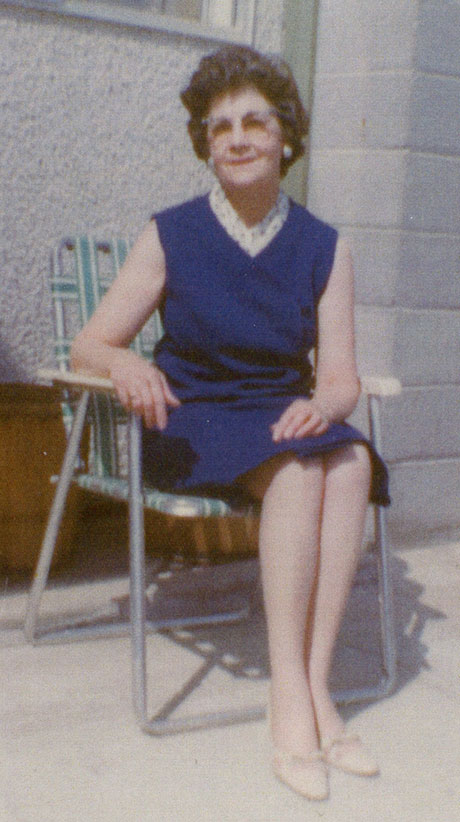

Dolly Gibb on 110th Birthday (right) – with daughter Sue Crozier. (Brittany Duggan)

Share

Few Canadians remember waking up to the news in 1914 that the country had entered the First World War. Or what it was like to start a family during the Great Depression of the 1930s. To remember and have lived through the early part of the 20th century, you’d need to be at least 100 years old. And though there are many Canadians who are centenarians, there is only one verified supercentenarian, defined as someone 110 or over. Her name is Ellen “Dolly” Gibb.

Gibb is Canada’s oldest citizen at 112 years old. She was born in Winnipeg in 1905, the same year Saskatchewan and Alberta became provinces and the Canadian Northern Railway was completed to Edmonton. Trudeau to her is still Pierre (though she admits to liking this new one). She’s witnessed 17 Canadian prime ministers and five reigning British monarchs.

As her great-granddaughter, I’m often asked the secrets to her long life. There are many. She never drove and did most errands by foot; never smoked and only started drinking in moderation in her seventies; she has basically eaten whatever she’s wanted, including full fat everything; and lived a relatively quiet life. But by tracking her life, especially on this anniversary of Confederation, we can also follow the growth and development of Canada alongside the biography of someone who was around to witness it. This year, many of us are reflecting on the last 150 years of Canadian history but for my Nan, this is looking back on her life.

Early life in Winnipeg, 1905-1920

Nan grew up on a small farm in St. Vital, Manitoba, now part of Winnipeg. Her father was a prospector who sought his fortune in the Klondike gold rush like thousands of other men who travelled north after gold was found there in the 1870s. Her mom was a Métis woman named Virginia Beauvette who died when Nan was just five after giving birth to Nan’s younger sister. As one of six children, Nan was raised by her aunt on her mom’s side and her older sister.

In the early part of the 20th century, childhood on a farm in Winnipeg was especially difficult in the winter. “The only heat to the second-floor bedrooms was from a floor vent where warm air from an oil burner and a kitchen cook stove kept the occupants from freezing,” wrote Bob Holliday, a community correspondent for the Winnipeg Free Press who lived on Nan’s street some years after she did. But it’s never the weather that Nan complains about when thinking of her younger years—it’s picking potato bugs off plants that she remembers vividly. To anyone who’ll listen, she’ll share this detail with fresh disgust and a little laugh—her mind wandering to all those years ago but never saying much more.

Gibb would have been 14 during one of Canada’s best-known labour actions, the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919. “It was incredibly dramatic,” Dr. Colin McCullough, a historian at Ryerson University, told me. “Labour groups in the city walked off the job. A group called the Committee of 1000, the city’s leading citizens, convinced the Canadian government that the labourers’ demands were illegitimate. The RCMP were called in, killed a number of protestors, and got many of the leaders deported, since they were often foreign born.”

When asked about early events like this, Nan mostly just shrugs. There’s not much about her childhood that she likes talking about. “Probably because it wasn’t very nice,” says her daughter, Sue Crozier. “Things were poor and a lot of people didn’t have work.”

Coming of age in Winnipeg, 1920-1940

Nan was given the nickname Dolly from her family at a young age. The doll reference became even more appropriate when as a teen she became increasingly interested in fashion. As a young adult, Gibb worked at the Eaton’s on Portage Avenue. She got to create fashion accessories for sale, like flowers from ribbons, and recalls when they installed the first escalator with particular delight. Sitting with her and talking about early Eaton’s is some of her most animated storytelling. She told me once that women were escorted to their departments from the employee entrance. But the stories all end with a sigh as she gets to the part about having to give up her job—a reality of the era she still seems sad to remember. “Very few professionals in Canada employed married women,” says historian McCullough. “In a lot of cases, they had to find more irregular forms of employment to add to their family’s incomes.” Which she eventually did.

In 1928, Nan married my great-grandfather, Dave, who was a schoolmate and metalsmith for the railway. Nan didn’t start drinking, the story goes, until after Dave died in 1968. She thinks he abused alcohol; their daughter Sue disagrees. “Mom thought he had a real problem,” she says, eager to set the record straight, “but I think kids today drink far more than he ever did.” For the time, though, hating alcohol and advocating for prohibition was part of the norm. It just wasn’t as socially acceptable for women to be casually drinking. Today, Nan’s a bit of a steward of alcohol consumption—she’s happy to have cocktail hour start but is quick to complain if she thinks anyone has had too much.

World War II and a life in Thunder Bay, 1941-2005

Nan and great-grandpa Dave had two daughters. One, my grandmother Eleanor, was born at the beginning of the Depression and the other, Sue, as it was winding down. In 1941, the young family moved to the Westfort area of Fort William, Ontario (now part of Thunder Bay) so that Dave could join the war effort at Canada Car building airplanes. “The country churned out thousands of military vehicles, ships and airplanes. It was one of this country’s greatest moments,” historian Jack Granatstein told the CBC in 2015.

World War II is filled with many proud moments for Canadians but for Nan, becoming a mother is what she’s most proud of. “That changed everything,” she says, remembering the little things like costumes that she made for her girls and the active role as a grandmother she assumed when they started families of their own.

[widgets_on_pages id=98]

Nan raised and supported her family as a homemaker, cook and seamstress. For a few years when Sue was a teenager, Nan became an Avon Products door-to-door sales representative. The job, according to a 1979 Fortune article, allowed “women to experience a degree of economic freedom without upsetting their culturally accepted role as homemakers.” It was also just an opportunity to get outside and socialize. “I still have some of the recipes mom collected when she’d be walking customer to customer,” says Sue. “You’d show up and people would be baking. My job was to deliver her stuff on my bike.”

After great-grandpa Dave’s death, Nan never remarried but enjoyed the close friendship of a widower who’d also gone to school with her and Dave (I’m told it was non-romantic). This friend would bring her along on business road trips so that she could visit family along the way—trips she otherwise wouldn’t have been able to afford, or at least not as frequently.

And though she has always been careful with money, she enjoyed bingo and gambling. Such activities were favourite pastimes with her daughter Eleanor before the younger woman passed away in 1991. Nan took her last trip to the casino in 2010. “Dolly was so excited to be there,” says her grandson Dave Crozier, “she wouldn’t leave the slot machine, afraid Bob [who’d taken her] would want to go home.”

When Nan wasn’t socializing, she concentrated on her crafts, crocheting cozy afghans and slippers, as well as elegant doilies and snowflakes. Her family today can now decorate their entire Christmas trees with the snowflakes we’ve received over the many years. In that way, our great-grandmother is no different from so many others. Where she has been unique, however, has been in her choice and ability to remain living in the same two-bedroom wartime home in Thunder Bay until just after her 100th birthday. That house is where grandkids remember visiting, cramming into the tiny space of only about 425 square feet.

Living independently for so long is one of the reasons many people credit for her longevity. There’s something a degree of independence and living with Sue that keeps her getting up every day. “My grandmother is the oldest helicopter mom,” says grandson Dave. “I’m sure that she’s sticking around to take care of my mom.” I wouldn’t disagree.

North Bay, 2005-present

At 100 and after almost 40 years of living on her own, Nan did finally move to live with her daughter Sue and son-in-law in North Bay. In her later years, casino trips remained a common activity, as did a lifelong interest and sometimes major concern with fashion.

“She was always so dressed up,” says granddaughter Sue Duggan. Nan didn’t wear pants in public until she had passed 100, preferring a daily uniform of heels and house dresses. She’s still quite particular about outfits, especially for special events like her birthday.

Birthdays at her age can’t help but being big events. Family and friends visit, send cards or, more recently, FaceTime and Skype with her. The last time I was there, she wanted to show me all the cards she’d received from Prime Minister Stephen Harper, Ontario’s Premier Kathleen Wynne, the Governor General and the mayor of North Bay. But it was really the note from the Queen that had Nan most excited. She wouldn’t let that one out of her sight.

Attachment to the monarchy is more typical of Canadians born before the 1930s, says historian McCullough. “She would have also learned about the glory of the British Empire in her elementary school education. Most classes had a big map of the world with all of the British possessions coloured pink. One of the national holidays when she was growing up would have been Empire Day as well, which would reinforce these connections.”

There are other details about her daily life that are truly Canadian. One being a love of Timbits from Tim Hortons. Another is her enjoyment of a daily beer, currently Coors Light. The support staff that visits her at home is one of the things that makes her most happy as she looks forward to each appointment throughout the day. A family member recently reminded me of how doctors would have done house calls when Nan was born and all these years later, they’re doing them again.

It’s really her desire to stay with us (she spends a great deal of time keeping track of her family) and her tenacity for life that form her secrets of longevity. When asked what advice she’d give to her 25-year-old self, she replied: “Put up a fuss for what you think is right. Fight back.” A sentiment that might be less stereotypical of a Canadian but true of so many individuals who have shaped this country’s landscape. We just might do it with a nationally characteristic please and thank you.