Health Canada’s latest weapon in the opioid wars: big yellow stickers

As of October, Health Canada will require high-visibility warning stickers and fact sheets to be included with every opioid prescription

Oxycodone-acetaminophen tablets. (Patrick Sison/AP)

Share

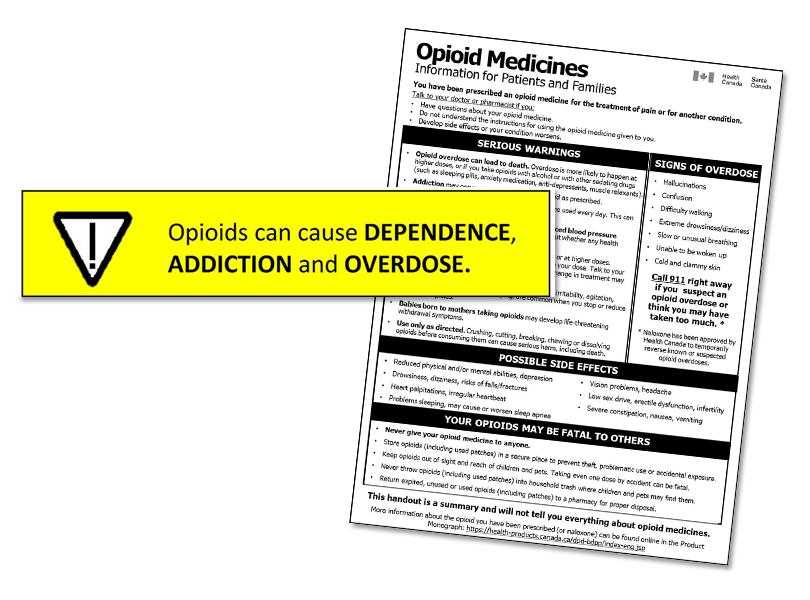

On Wednesday, Health Canada announced new measures aimed at combatting the opioid crisis that killed an estimated 4,000 Canadians in 2017. The new regulations will require bright yellow warning stickers on every bottle of opioid painkillers dispensed at a pharmacy, along with mandatory patient information sheets, beginning in October 2018.

In a press briefing, the health agency’s chief medical advisor, Supriya Sharma, explained why these steps are necessary and how they might help. “What we heard from patients and practitioners is that there were a lot of people going and getting their prescriptions filled not even knowing that the medication they were getting was an opioid,” she said. “And certainly we’ve heard—at least anecdotally—that they weren’t being made aware of the significant risks…specifically speaking around dependence and the potential for addiction and overdose.”

MORE: These are the provinces where the opioid crisis is most severe

Jeff Blackmer, vice-president, medical professionalism with the Canadian Medical Association, says he hasn’t seen any evidence “that even hints at the possibility” that doctors aren’t having serious conversations with their patients when it comes to prescribing opioids. If anything, he argues, doctors are so hyper-aware of the risks and close scrutiny of their prescribing practices right now that they’re proceeding very gingerly.

“As you can imagine, this is a highly sensitized issue for the medical profession right now,” he says.”If you could have made the argument 10 years ago that this wasn’t happening, I certainly don’t think you could make it today because of the attention that’s been paid to all of this.”

However, research shows that patients forget between 40 and 80 percent of what their doctor tells them once they leave the office, Blackmer says, and of the information they retain, about half is incorrect. So it’s very possible that patients in a stressful situation emerge from a medical appointment unclear on the exact nature of the prescription in their hands, and in that case, an information sheet and warning sticker on the bottle could be useful. “I don’t think it’s in any way a reflection on the fact that these conversations may not be happening,” Blackmer says. “But I think it’s another reminder to patients who may be in a lot of pain, may not take in all the information.”

David Juurlink is a specialist in internal medicine and clinical pharmacology at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre at the University of Toronto, and he was one of several clinicians who helped develop the information sheet and warning sticker in consultation with Health Canada. To him, the value of these tools is in offering badly needed clarity.

There’s so much discussion of “the opioid crisis” swirling about, but people tend to think of that as being about synthetic opioids like fentanyl and people dying of addiction, he says. They may not realize that opioids are also drugs that are prescribed for acute or chronic pain, with serious potential side effects. “I think it’s really important that people know what they’re getting into when they start a prescription for opioids,” he says.

Juurlink spent five years as a pharmacist earlier in his career and affixed “thousands” of warning stickers to prescription bottles. Patients often don’t get a full picture of the benefits and risks of a medication, he says, and even now, doctors are sometimes unaware of the subtler side effects of opioids or the potential for dependency even after a short course of medication. To that end, he likes the plain language on the information sheet and the eye-catching nature of the warning stickers.

“I do think that some chronic pain patients are going to be upset by it. I think that’s the unfortunate cost of doing business,” he says. “This issue has to be addressed. Public education is part of the solution, and it means being blunt with people.”

In an emergency room setting, doctors have to discuss the nature of the medication they’re prescribing because they must check for allergies, says Andrew Affleck, an ER doctor at Thunder Bay’s Regional Health Sciences Centre and co-chair of the public affairs committee for the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. But they might be more likely to identify a painkiller as Tylenol 3 or Percocet, rather than calling it an opioid, he says.

“There’s certainly a role for opioids in some pain control, it’s just when they’re overused or if the patient isn’t aware of the very addictive potential of them that you run into problems,” he says.

He applauds any effort aimed at combatting the public health crisis, but argues there needs to be a comprehensive approach, not just discrete little jabs at specific aspects of a sprawling, complex problem.

And physician education is key. In January, Affleck attended a seminar on opioid prescribing that addressed topics such as talking to patients more, being aware of the potential for addiction even with short-term doses and the symptoms of withdrawal. “It did change my practice, immediately,” he says. “I believe I was more on the conservative side. Now I’m just as conservative, but explaining more to patients.”

To Jeff Sisler, a family doctor in Winnipeg and executive director of professional development and practice support for the College of Family Physicians of Canada, these new measures provide one more layer of information and security when it comes to opioids.

There is a defined protocol around discussing any new prescription, he says: you explain what the drug is, how to take it correctly, what the expected benefits are, what are common side effects and more rare but concerning ones, and what are the alternatives to the given drug.

“With opioids, the bar is a bit higher in that there’s also a recognition that one has to screen patients carefully and that safety—in particular around medication storage—is important,” Sisler says. But that doesn’t mean every patient leaves the office with the clear facts they need, he says, and that’s where a simple mechanism like warning stickers and an information sheet could be crucial.

“It’s a good safety net,” he says.