History’s lessons on dealing with Canada’s neo-Nazi groups

Canada has long been home to hate groups—and two moments, in 1938 and 1965, show us how best to handle today’s strain

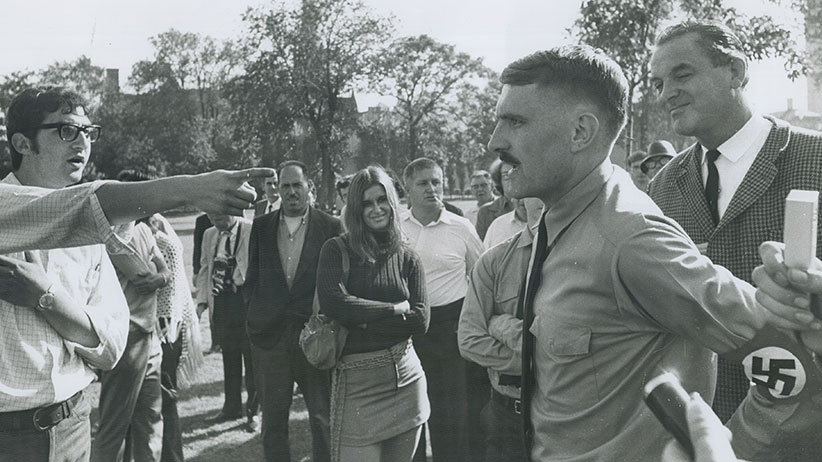

CANADA – SEPTEMBER 20: William John Beattie (Reg Innell/Toronto Star/Getty Images)

Share

Christine Sismondo’s Canadian Moments series looks at what history can teach us about a current moment in Canadian news, politics, or culture. Read more of her columns here.

Although the group is at least a year old, the “Proud Boys”—a group of self-described “western chauvinists” with a “street-fighting” program—are making its presence known on the country’s sesquicentennial. On July 2, five of the “boys” disrupted a Mi’kmaq protest over the institutional, symbolic support for the colonial legacy of genocide. Two weeks later at Queen’s Park in Ontario, a University of Toronto group called the Students in Support of Free Speech—supported by the likes of Paul Fromm, one of the GTA’s better-known white supremacists—echoed support for the chauvinists, a rally that made the news, at least in part, because anti-fascist activists arrived to confront them. Whether or not Fromm was explicitly invited to take part is unclear, but he was there, ready to share his views, megaphone in hand.

Between this and several other incidents—including the establishment of a Hamilton neighbourhood watch group called the Sons of Odin, a recent neo-Nazi meeting held at a west-end branch of the Toronto Public Library, and the Canada Post’s refusal to distribute the controversial paper, Your Ward News—the realization that extremist groups were alive and well in Canada has been a shocking surprise to many.

That’s just as it was for the majority of Torontonians on May 31, 1965, when they picked up the Toronto Star and read about the previous day’s full-blown riot at the Allan Gardens conservatory. Thousands of people, some of them survivors of the German concentration camps, descended upon the park to protest a neo-Nazi rally, expected to attract about 50. In the end, it turned out to be eight, severely outmatched by an estimated 4,000 anti-Nazis. The hateful eight was led by William John Beattie, a 23-year-old who “barely made it out of his car,” tried to run, but was grabbed and beaten by the “hate-filled” and “hysterical” mob. Somehow, though, Toronto police managed to gain control of the situation after only about 15 minutes of chaos, despite the fact the force had little recent experience with that kind of incident. Police chief James Mackey said there hadn’t been anything like it in the city since the 1930s.

It’s unclear what event from the 1930s Mackey was referring to, since Toronto was awash in fascist sentiment in that era. It may have been a reference to the 1933 Christie Pits riot, a violent six-hour clash between Jewish baseball fans and the “Pit Gang,” a group of Nazis emboldened by the rise of Hitler in Germany. He could have been referring to another incident involving members of the region’s many Swastika clubs—anti-immigrant groups that included the Pit Gang and have been compared to the paramilitary vigilante groups of fascist countries in Europe. Ontario wasn’t alone, either, of course; there were Brown Shirt organizations in Winnipeg, anti-Semitic Social Credit Party events in Alberta and, most famously, the National Socialist Christian Party, a Quebec faction led by Adrien Arcand—who referred to himself as “Canada’s Fuhrer”—that advocated deporting Jews to Hudson’s Bay.

In 1938, Arcand took his party on a limited tour outside of Quebec in an attempt to unite regional fascists under his national party. More than a thousand people gathered to hear him speak at Toronto’s Massey Hall and, while there were attempts at anti-fascist demonstrations, the police, at Mayor Ralph Day’s behest, prevented crowds from forming, so that incidents were few and far between. A group of girls did manage to sneak into the area and proceeded to whip off their coats to reveal anti-fascist slogans painted on the back of their white sweaters. Most of the energy was channelled into other, orderly rallies instead, such as the one less than a kilometre away at Maple Leaf Gardens, organized by the League Against War and Fascism, which attracted a crowd of 12,000. There, the former U.S. ambassador to Germany William Dodd spoke alongside a leader of the socialist-leaning Co-operative Commonwealth Federation and a Methodist priest with strong labour sympathies. The trio argued for a firm commitment to democracy, national unity, a stand against fascism, co-operation amongst allies, and workers’ rights. The crowds listened attentively and cheered for these progressive goals. Although Arcand would continue to try to gain support for his vision for Canada until 1965, that had been the beginning of the end for him; support for fascism plunged during the Second World War.

Not that it was entirely eliminated, though; there’s always an undercurrent. And, by the late 1950s, holocaust denialism had become more common, thanks to Arcand’s continued efforts to disseminate conspiracy theories, amid reports of the occasional swastika daubing. In the early 1960s, Beattie and his group began to distribute anti-Semitic hate literature in Toronto, which is why Jewish communities in Toronto were on guard and ready to show force at Allan Gardens in 1965.

You’d think we’d hear more about this massive riot that, to many, came out of nowhere. One of the reasons we don’t, though, is that the Allan Gardens incident is a messy story from which it’s difficult to draw out a simple, clear-cut moral. Innocent bystanders were hurt and, as the Toronto Star editorial board pointed out, mob violence was playing right into the neo-Nazis’ hands. A year and a half later, when Maclean’s published John Garrity’s “My Sixteen Months as a Nazi”—the firsthand story of an infiltrator who gained Beattie’s trust—the Toronto Star’s views were confirmed. Garrity wrote that publicity was the most important thing to Beattie and his gang: “‘Just think,’ Beattie once told me, ‘Three or four kids. That’s all we were. And we had the country all up in arms.’ ”

Still, Garrity never dismissed the danger inherent in that wave of fascism. Although he wasn’t losing sleep over Beattie, he still worried about the uncounted “Nazi sympathizers, and the growing number of anti-Communist, right-wing organizations that display neo-Nazi symptoms,” and feared the prospect of an “intelligent demagogue” who could tap into the legions of lurking sympathizers.

Beattie didn’t turn out to be that person, however. Even though he continued to hold rallies in the park, his movement fizzled out, partially because he wasn’t actually all that dynamic or novel, and was—as historian Frank Bialystok points out—a terrible orator. The numbers he led were small, and the best publicity he got was the media coverage and public dismay that such horrific events could be happening in Toronto the Good. Judge Sydney Harris, notes Bialystok, said that if the Jewish community had ignored the neo-Nazis from the outset, the movement would have died.

There was some upside to the Allan Gardens riot; Bialystok argues that, even though the incident is rarely remembered as any kind of turning point, it actually marked the birth of a new collaboration between Jewish communities that were previously divided, roughly according to when they had immigrated—prior to, or after the war. But, today, whether we’re dealing with actual neo-Nazis or merely street-fighting western chauvinists, there are perhaps wiser lessons to be drawn from 100 years of dealing with extremist groups in Toronto. Four thousand people turning up at Allan Gardens in 1965 only amplified the neo-Nazis’ message; 12,000 people showing up at Maple Leaf Gardens in 1938 helped to drown out the hate being spewed at Massey Hall.

It’s not wrong to be concerned about the extremist movements cropping up. But we have to be careful not to give these attention-seekers the megaphone: they’ll only use conflict to amplify their message. The answer, instead, is to drown them out by making broad coalitions and working together towards education, truth and reconciliation, social equality and representative democracy. It worked in 1938—and it can work again.