Houses of hate: How Canada’s prison system is broken

Justin Ling: Dangerous, racist and falling apart. By nearly every metric, the nation’s penal system is not just failing, it’s making things worse.

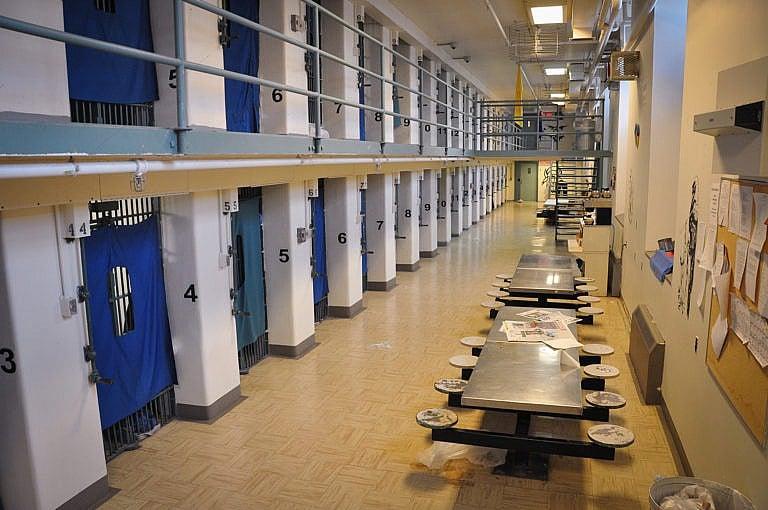

Medium security range at Stony Mountain Institution in Stony Mountain, Manitoba (Correctional Services Canada/Flickr)

Share

Michael Ignatieff was staring right at the Prime Minister. “I worked in a prison when I was a younger graduate student,” he said. “I worked with lifers. I’m utterly unsentimental about criminals, but one thing I know about prison: It’s that prison makes almost everybody worse who’s in there.”

It was a rare personable moment for Ignatieff, who normally has the air of a university lecturer, and it came in the middle of the televised leaders’ debate. “You’re going to end up with more crime problems, not less,” Ignatieff said, imploring Stephen Harper to drop his $13 billion plan for stiffer prison sentences and megaprisons. His hands held aloft, in front of the television cameras, he said it’s high time for an “adult solution.”

It’s been a decade since that debate. Today, with COVID-19 running rampant in prisons (nearly one in 11 federal inmates have contracted the virus, despite assurances from Ottawa that everything is under control; five have died) and new reports that inmates are still being tortured through the use of solitary confinement (in violation of both court orders and the government’s own laws), things seem worse than ever.

In fact, by nearly every metric, found in a veritable mountain of reports from Correctional Services Canada and its watchdog, the Office of the Correctional Investigator, our penal system is badly broken.

- Our prison system is dangerous: There were five murders in Canadian prisons last year, making the homicide rate in our prisons 20 times higher than Toronto. In a year, correctional officers deployed force more than 2,000 times. More than 60 per cent of prison staff were subject to physical violence. The Correctional Investigator reports “there is no overall strategy that specifically and intentionally aims to prevent sexual violence in Canadian federal penitentiaries.”

- Our prison system is racist. There are more than 12,500 inmates in our federal system: Nearly one-third of them are Indigenous, eight per cent are black. Upwards of three-quarters of the prison population in Manitoba and Saskatchewan are Indigenous. Black and Indigenous inmates are both twice as likely to be subject to use of force, more likely to be classified for maximum security, more likely to be involuntarily put into solitary confinement, and less likely to be paroled.

- Our prison system is falling apart. Many prisons ought to be condemned and torn down. Four are more than a century old, and another two are nearly that old. The infrastructure is crumbling and the technology running the prisons is antiquated.

- Our prison system is warehousing people struggling with their mental health. It is estimated that at least 10 per cent of inmates meet the criteria for fetal alcohol syndrome, 80 per cent have substance abuse issues when incarcerated, while some 45 per cent have antisocial personality disorders.

- Our prison system is eye-wateringly expensive. Correctional Services Canada (CSC), with its $2.6 billion budget, is the 15th largest department or agency by spending — it is larger than the CBC and Department of Justice combined. Ranked by the number of staff, it is the sixth largest department. It costs CSC $110,000 per year to house each inmate, with about three-quarters of that number going to employee costs.

- Our prison system isn’t even working. All available evidence shows that our prisons are doing little to reduce crime, and may even be increasing it. More than 40 per cent of all inmates released are returned to custody within two years, usually on parole violations. About a quarter of all those released from prison are convicted of a new offence within those two years, although most charges are non-violent.

This is just federal prisons. There are another 39,000 Canadians sitting in provincial jails, most awaiting trial.

Over the past year, Maclean’s has spoken to dozens of current and former inmates, consulted a host of correctional officers, support staff and lawyers, and consulted thousands of pages of Access to Information documents. It all reveals a racist and discriminatory system that is in crisis. We, as a country, are warehousing our social ills, while offering little in the way of self-improvement, rehabilitation or redemption.

It proves exactly what Michael Ignatieff told us a decade ago: Our prisons make things worse. The only people who still believe this system works are our feckless politicians.

***

It’s hard not to feel like history is repeating itself.

Many Canadians, when asked to imagine our prisons, may immediately conjure up the scene of Agnes MacPhail touring Kingston Penitentiary, immortalized in the Heritage Minutes which saturated Canadian television through the 1990s and 2000s. In the spot, MacPhail, the first woman elected to the House of Commons, glares, shocked, at the sight of inmates being whipped mercilessly as they are hanged by shackles from their arms. When MacPhail stands in the House to highlight the injustice, she faces sexist heckling from the government benches. Undeterred, she slaps a crop onto her desk and cries: “Is this normal?”

In reality, MacPhail had to spend years hammering the government before it sought even modest reforms. She cited report after report from the government’s own watchdog, raising the alarm about those inhumane conditions. She lamented the over-incarceration of Canadians, the pittance the inmates were paid for their manual labour, and the solitary confinement cells that inmates were thrown into indefinitely. Worst yet, she said, the prisons didn’t seem to be reducing crime at all. “There is something radically wrong with a system that produces such a condition,” she told the House in April, 1935. She was consistently ignored. Government MPs regaled the house with stories of how things were just fine in those prisons.

MacPhail wasn’t the only one. Austin Campbell, jailed for financial misdeeds in the lead-up to the stock market crash, wrote the “House of Hate” column for this magazine from inside the Kingston Penitentiary throughout 1933. “I have watched men during the last few weeks and days of their time,” he wrote of the solitary confinement cells. “Men who were decent fellows all the long months went to pieces in the last few days”

Nearly a century ago, MacPhail lamented that Stony Mountain Institution, in Manitoba, was dangerous and unfit for habitation. It is still open today. The main wing is nearly 150 years old. Nearly 800 inmates live there, a sizeable majority of them are Indigenous. It was the site of one of the worst COVID-19 outbreaks, with more than 350 inmates testing positive.

Zilla Jones, a Winnipeg-based criminal lawyer, has represented several inmates at Stony Mountain. “It’s freezing in the winter and unbearably hot in the summer,” she told Maclean’s. It’s so bad, she has to keep her coat and gloves on while she meets with her clients, and she still shivers. It’s “not comfortable in terms of human habitation” she says. (A newer wing of the prison was completed in 2014, and is better suited for human habitation.)

“It’s a pretty crappy building but it’s what happens inside that’s worse,” says Jones. “They can fix up the building all they want, but it’s not going to change the culture that’s inside.”

Jones provides “a prime example of life at Stony” — a client who was arrested on a breaking and entering charge. “I begged the judge not to send him to Stony Mountain,” Jones says. Her client was just 18 years old. She told the court: “Give him a provincial sentence, so at least he wouldn’t get influenced by the gangs.”

Her pleas were ignored, and the teenager was sent to Stony Mountain. Not long after, he was recruited by a gang to attack a fellow inmate—one who had been identified, by a guard, as a sex offender. The teen was convicted of a new charge, meaning his stay at the notorious prison was extended.

“I don’t know why we would send anybody there,” Jones says. “What are we doing? Warehousing people in a violent place so we can feel like justice is done.”

Some gangs are given their own sections in the prison. A corrections officer told Maclean’s that segregating members by gang affiliation is done in hopes of keeping the rival groups apart, in order to prevent violence. Some inmates enter the prison already linked to a gang, but many affiliate in order to protect themselves, or to get in on the lucrative drug-running business. Money has been poured into drug-sniffing dogs and body scanners, and yet the proliferation of drugs within the prisons has continued, unabated. In 2017, 70 inmates overdosed inside our prisons.

One corrections officer who works in the prairie region, who was not authorized to speak on the record, explained that the “unbelievably dated” infrastructure can put corrections officers’ lives at risk, too. The archaic technology that runs their system can cause delays in opening doors or accessing the right monitors, “which makes our jobs a lot more dangerous.”

While prisons no longer chain inmates standing up, solitary confinement cells do not look tremendously different than “the hole” that Campbell saw. Canada still locks inmates in tiny, windowless cells for 22 hours a day, or longer, for months or years on end. That meets a United Nations definition of torture, a definition which Canada has endorsed. Nevertheless, Ottawa defended the practise, insisting on branding it “administrative segregation.” The courts took dimly to that euphemism, calling it what it truly is: Solitary confinement, and unconstitutional.

Two years after the first court ordered that Ottawa must stop the practise, in June 2019, the Trudeau government finally adopted legislation to replace them. They rebranded the new isolation cells as “structured intervention units.”

The new system is supposed to add safeguards and mental health supports. They are supposed to give inmates more time outside their cell and meaningful human contact. The cells themselves were spruced up: Some with a new coat of paint and a poster, but other units give inmates access to televisions and more comfortable accommodations.

But the data show things haven’t improved overall.

Respected criminologist Anthony Doob was initially tapped by the Trudeau government to study the supposed elimination of solitary confinement in favour of new “structured intervention units.” He was thwarted for more than a year, before media attention pushed the government to hand over the data. His most recent report, from February, shows just how bad things are: “We estimate that 28.4 per cent of the SIU stays qualified as ‘solitary confinement,'” he writes. “And an additional 9.9 per cent of stays fall under the definition of ‘torture or other other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.'”

The law requires inmates get four hours outside their cell per day. That isn’t happening. The courts have said anything less than two hours is cruel and unusual punishment. It has continued anyway.

Correctional Services Canada has rejected the findings, alleging Doob got the data wrong.

The year-long saga of the data lends credence to the idea that the reforms were just, as the B.C. Civil Liberties Association put it, “window dressing.” Senator Kim Pate, who has spent nearly four decades advocating for real prison reform, had warned from the outset that the supposed reforms would actively “make things much worse.”

CSC reported that, since last December, it has reviewed 1,100 placements in the new units. A quarter of those reviews recommended CSC take additional steps to improve the conditions for the inmate, while just 2.5 per cent of reviews recommended the inmate be released from isolation. This new regime has implemented new bureaucracy without substantially changing the practise, which was blasted by courts in two provinces as unconstitutional—a finding that the federal government, eventually, accepted.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, plenty of inmates learned that the difference between the old cells and the new ones didn’t amount to much. Prisoners showing symptoms of the virus were thrown in the old solitary confinement cells, being let out for just 20 minutes a day to shower or make a phone call.

Blair told Maclean’s those measures were “necessary” given the pandemic and that they “were not intended in any way to to violate anybody’s rights.”

Some prisons are even worse. A lawsuit filed by inmates in the “special handling unit” at the prison in Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines, Que., allege that they are kept in solitary confinement for upwards of 22 hours a day. The unit, which is designed to handle dangerous sexual offenders, encourages inmates to undergo chemical castration. While it is not supposed to be required, one inmate said in an affidavit that “I believe I will never be transferred from the SHU unless I take this treatment.” CSC insists inmates in that unit “have the same rights and conditions of confinement as other inmates, except for those that must be limited due to security requirements.”

While CSC Commissioner Anne Kelly declined to be interviewed for this story, Maclean’s asked her about the state of solitary confinement in Canada’s prisons during an unrelated press conference. “We do not have solitary confinement any longer,” she said, insisting that the structured intervention units had been successfully implemented, aside from “some hiccups early on.”

Pressed on the data from Doob, which clearly shows that CSC is practising the definition of solitary confinement, Kelly put the onus on the inmates. “In some cases the inmates actually do not want to come out of their cells, despite the repeated attempts that we make for them to avail themselves of the opportunity,” she said.

***

On Dec.14, 2016, at 1:30 in the afternoon, officers at the Saskatchewan Penitentiary read the riot act over the prison’s loudspeakers. Inmates had joined in a prison-wide strike, barricading their rows of cells, protesting the harsh conditions inside and shrinking food rations. More than a quarter of the whole prison joined the action, primarily in the medium-security unit.

The prison called in crisis negotiators and took to the loudspeaker to demand the inmates return to their cells and lock up. They ignored those calls. Officers armed with batons and shotguns were deployed to the ranges, battling inmates hurling burning debris.

When the riot was cleared, officers found the body of Jason Leonard Bird. He had been beaten and stabbed to death by other inmates, for unknown reasons. Bird was serving a two-and-a-half year sentence for breaking and entering.

An internal review concluded that the riot was caused, in large part, because the state of the food at the prison. Kitchen staff had warned the warden that funding cuts meant they couldn’t adequately feed the inmate population.

It’s a widespread problem. The Correctional Investigator found that more than one-in-five meals served in federal prisons failed to meet basic Canada Food Guide requirements, CSC failed to respect prisoners’ dietary restrictions, the meals are sometimes prepared in unhygienic conditions, and that a significant amount of food was being wasted.

Internal spreadsheets tracking the nutritional value show that, if a prisoner were to eat every morsel of food on their plate, they would get about 2,600 calories a day — Health Canada recommends active adult males actually need about 2,900 calories. The meals also wildly exceed Health Canada guidelines for both fat and sodium intake. (Correctional Services wrote in an email statement that they follow a “comprehensive set of nutrient reference values for healthy populations” in designing the meals.)

These problems can be traced back to an attempt to centralize food production. In 2014, to save money, CSC changed to a “cook-chill” model, where food was prepared at regional hubs, frozen, and shipped to the prisons, where it would be reheated.

“People thinking that we get good food in here? Oh my god, that’s—” says Norman Larue, a prisoner at the Pacific Institution. “Ouf.”

Larue works in the kitchen. As he explained to Maclean’s, there was suddenly a lot less work to do after cook-chill came along. “Today, it was a mac and cheese for lunch,” he says. “About two days ago in the kitchen, I cooked and prepared, on site, the actual macaroni noodles, and that’s it. Everything else comes in a bag.” Larue says that the amount of food served to prisoners is “barely enough to keep a guy alive.” A corrections officer told Maclean’s that “any massive riotous situation we face in the next five years is going to be because of the food.”

The cook-chill model has meant CSC spends about $2,300 per inmate, per year on food. About $5 a day.

Blair dismissed the idea that something is structurally wrong, but said “there may be individuals, because of their level of physical activity or other health considerations, that have unique requirements” and some “may desire more.”

I asked Blair: Could you stay healthy on a diet worth $5 a day?

Blair demurred. “I can’t do a calculation based on the dollars and cents in question.”

***

The problems in prisons go far beyond the size of the cell, the food, or the physical infrastructure.

Inmates are frequently upgraded to higher-security facilities, which are more dangerous and offer fewer supports, sometimes on vague and subjective criteria. One inmate was upgraded to medium security because he “exhibited a negative attitude and engaged in repeated rule infringements.” Racism plays a role, as well, as a 2013 Correctional Investigator found that when it comes to Black inmates, “body language, manner of speaking, use of expressions, style of dress and association with others were often perceived as gang behaviour by CSC staff.”

A Globe and Mail investigation from October found Black and Indigenous inmates are significantly more likely to be rated as a security threat, despite the data showing them less likely to reoffend than white offenders.

Paul Gallagher, an Indigenous inmate also incarcerated on drug trafficking charges, was upgraded from minimum to a medium-security facility because CSC was looking to open an Indigenous-oriented wing and “they needed the numbers.” He filed a grievance and won, yet he still hasn’t been moved.

Grievances, one of the only ways in which inmates can seek redress, are supposed to be answered within four months. In reality, CSC admits, they take up to three years to be resolved. Inmates can, technically, petition the courts over their treatment, but that is rarely effective: When one inmate filed a habeas corpus application to a provincial court over the conditions in his prison, the court dismissed the case, ordered him to pay the Attorney General’s costs, and banned him from making any other application with the court.

Not every officer is part of the problem. Well-intentioned and well-trained corrections officers are plentiful. “As soon as they walk in the door, before they go to their cell, we give ‘em a speech,” one corrections officer said. “Like: ‘This is easy time for you, here, if you treat us with respect.’” Good officers are happy to do the “thousand little things that they need help with,” he said. “We have relationships with these guys. And that way, when something serious is happening, they listen to us.”

The officer said not every prison was as supportive of the inmates as his. Even still, officers don’t get to decide who gets incarcerated or not—they just have to manage it.

Prisons constantly struggle to handle the number of inmates with severe mental health issues. “We’re law enforcement officers, we’re not psychologists,” the officer says. There are mental health workers who visit the prison, they aren’t around on evenings and weekends. “We do take a little bit of training on these kinds of topics. But I mean, it’s like a day of training, you know?”

The Correctional Investigator has consistently found mental health support lacking, actually finding that officers in one women’s prison punished inmates who self-harmed. Problems are particularly acute for transgender inmates, some of whom are still being housed in prisons that do not match their gender identity, and who are often placed in isolation, ostensibly for their own safety.

Sentenced time is supposed to be “productive,” yet that’s rarely the case. There are schooling programs, but they are largely one-size-fits-all—a former inmate, with a university degree, recalled having to sit through the equivalent of Grade 8.

There are Indigenous-focused programs, but access is spotty. Inmates have some access to computers, but are cut off from the internet. CSC directives still refer to “floppy diskettes.” The jobs available are generally menial light labour, and provide little in the way of marketable skills. Work is often necessary, however, as inmates are required to pay for food to supplement their diet, and are charged by the minute by the phone system. The most an inmate can earn is $6.90 per day, although the prison deducts “room and board” costs from their salary.

But when even that inadequate programming goes away, like they did during the COVID-19 shutdown, “it was just violent,” the corrections officer reported. “It was a nightmare, there was overdoses and suicide attempts and stabbings every couple of days.”

***

The closer you look at Canada’s prisons, the more the absurdity of the practise becomes obvious.

It is unavoidable that some inmates need to be locked up: About 800 inmates are currently designated as ‘dangerous offenders,’ meaning they can’t be released. About a quarter of the federal prison population is serving life or indeterminate sentences.

Yet more than 30 per cent of that population is incarcerated on non-violent offences, mostly drug and property crimes. Critics have wondered for years: Why do they need to be in the violent confines of federal prison, counting down days at the expense of the Canadian government?

Less than 40 per cent of applications for full parole are granted. For those offenders who are granted release, there’s often no place to go: In 2018, the Auditor General found that halfway houses and community programs for released offenders were generally full: Some inmates who were cleared to be released have continued to sit in prison because there is not enough space in those houses.

A 1987 report from the Canadian Sentencing Commission laid out the problem at hand succinctly and blunt. Canada’s over-incarceration problem, it read, “cannot be eliminated by tinkering with the current system or exhorting decision-makers to improve what they are doing.”

When he took power five years ago, Justin Trudeau promised more restorative justice, to reduce the over-incarceration of Indigenous peoples, and to end the practise of solitary confinement for good. He has taken a knee with Black Lives Matter protesters, and has vowed to heed the calls to action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, In his government’s September throne speech, he promised, again, “to address the systemic inequities in all phases of the criminal justice system.”

Yet what does he have to show for it? His government has lengthened the maximum prison time for many sentences. As of January 2019, government lawyers were defending against 173 separate constitutional challenges to mandatory minimum sentences. Lawsuits are targeting his government’s handling of COVID-19 in prisons, the exploitative nature of prison labour and Quebec’s Special Handling Unit. There is still no cap on the number of days someone can be placed in solitary confinement. The over-representation of Indigenous and Black people in prisons is getting worse, not better.

A February report from the Correctional Investigator found scant evidence that the federal government depopulated prisons in the past year, but did find that the overall prison population declined, due to a drop in crime, court delays, and judges looking for alternatives to incarceration amid a pandemic. Even then, Indigenous peoples benefited least. Zinger found that “the non-Indigenous inmate population declined at twice the rate of the Indigenous inmate population.”

Even still, the decline in population led Zinger to recommend that Ottawa should consider “closing a number of prisons and reallocate staff and resources to better support safe, timely and healthy community reintegration.” The Trudeau government has made no indication that it intends to follow that advice.

“We promised significant criminal justice and prison reform and we haven’t seen that reform come to fruition in a real way,” Nathaniel Erskine-Smith, a Liberal Member of Parliament, told Maclean’s.

In February, Justice Minister David Lametti introduced new legislation to finally repeal some mandatory minimum penalties. The legislation also expanded the use of alternatives to incarceration, and created new principles to encourage police and prosecutors to avoid pursuing drug charges—essentially adopting legislation previously introduced by Erskine-Smith.

While the legislation was lauded for what it did, it was also pilloried for what it didn’t do. Pate, who was appointed to the Senate by Trudeau in 2016, calls the legislation “justice for some, not all,” saying that by leaving the majority of mandatory sentences on the books, it “stopped short of taking the kinds of bold steps we need right now.”

Canada’s prisons are antiquated, inhumane, violent, and expensive. They don’t even work. Two decades ago, researchers from the University of New Brunswick did a meta-analysis of 50 studies on incarceration, spanning a half-century. They could not find “any evidence that prison sentences reduce recidivism” and that “prisons should not be used with the expectation of reducing criminal behaviour.” They revisited the study two years later, looking at 100,000 inmates. They found the same result: Prisons do not reduce crime, they increase it.

We’ve been warned about this time and time again. “The constituency in favour of prison reform and—where practicable, decarceration—is always small,” Ignatieff told Maclean’s. He tried, just like Agnes MacPhail, to fix it.

“Politically, it all went nowhere.”