How reporting on a murder trial stirred memories of my brother’s death

What I learned from the justice system as a sibling of a murder victim—and then, years later, reporting on the high-profile murder case

Share

I can still hear my father waking me up in the middle of the night at the age of 15 on May 15, 2001, the rushing panic in his voice as he spoke.

“Get up. Watch the kids. Yancy’s been stabbed. We’re going into town.”

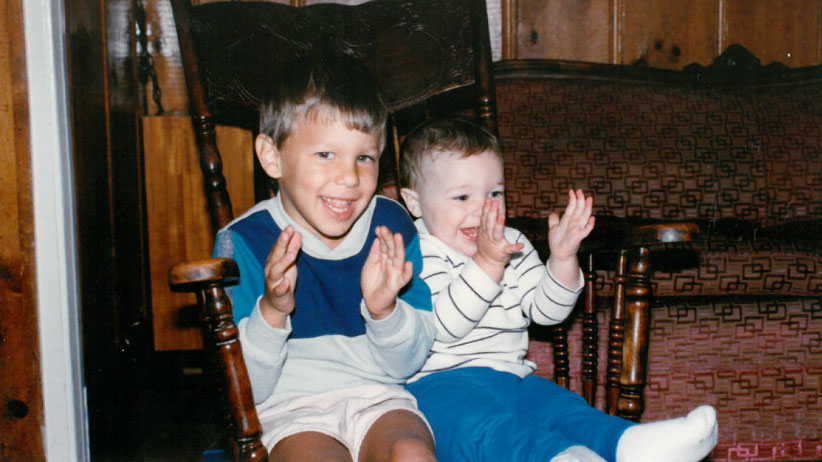

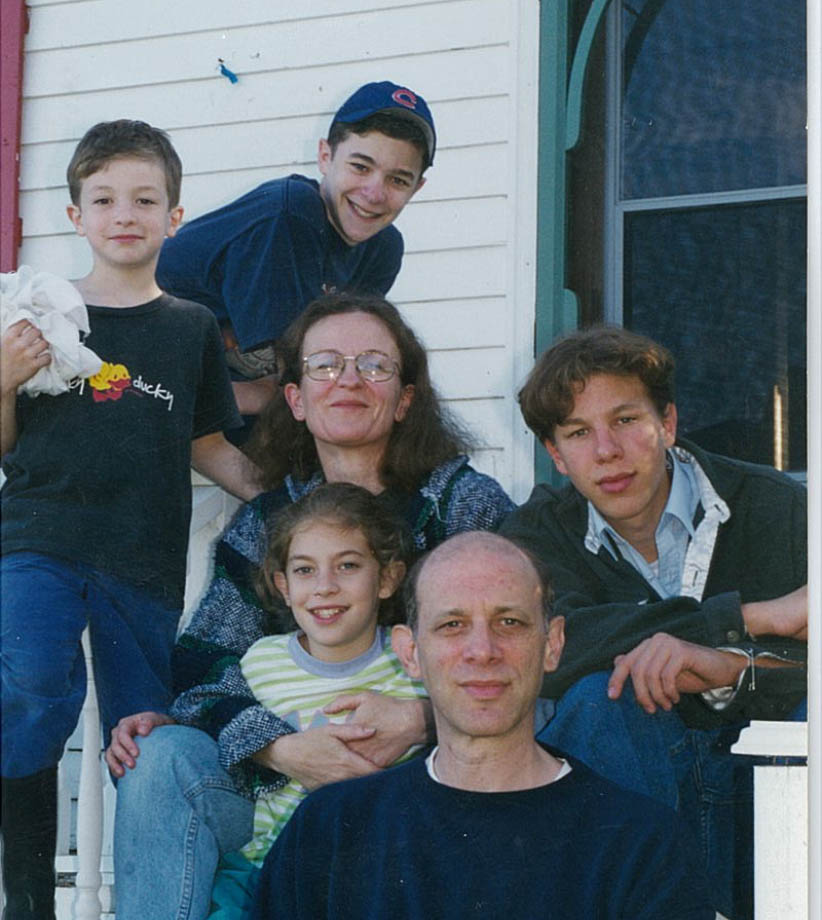

Yancy, my brother, who didn’t let attention deficit disorder and early high school bullying stop him from pursuing his acting talents and building friendships. My brother, who had just completed his first year at St. Francis Xavier University, where he had also found the love of his life. My brother, who was a role model to his three younger siblings, and the first-born pride of our parents. My brother, who was just 19.

He was all those things and more when he was working the overnight shift at a convenience store in Antigonish, N.S., when another man entered wearing black clothing and a Halloween mask. It was in that store that the man attacked him while he was away from the register doing other duties, stabbing him as he fought back, then trying to pry open the cash register in the botched robbery before fleeing. It was that day—our father’s birthday, and one day after our mother’s birthday—that he managed to crawl to his nearby apartment and find his roommate. After two operations at the local hospital, he was airlifted to Halifax, my mother making the drive with a friend as the rest of us stayed behind.

Waiting.

Later that night, the phone rang. My father picked up.

“Oh no,” I heard him cry from upstairs.

Due to his multiple injuries, not enough oxygen had reached Yancy’s brain, my mother told my father. He was pulled off of life support. He was gone.

After several weeks of intense RCMP investigation, the perpetrator was found, but meanwhile, our family found itself suddenly thrust into the spotlight of media attention and the focus of our small town. Amid the unplanned memorial services was also the alien atmosphere of the courthouse. Despite the case not going to trial—the killer eventually pled guilty to second-degree murder—the ordeal lasted around a year until the sentencing date arrived and victim impact statements were read.

Standing several feet away from the man who took your hero’s life is a most disordered position: a glut of emotion bubbling on the inside, which must be subdued from outward expression, so as not to disturb the court. After I spoke that final day in court, I watched as my brother’s killer was taken away, knowing I would never be in the same room as him again.

Little did I know then that I would return to the halls of justice—not as a victim’s family member, but as a journalist more than 15 years later, covering the high-profile Douglas Garland murder trial in Calgary. It was a trial that would examine a series of crimes that began with petty revenge and escalated into ghastly inhumanity with the killing of Alvin and Kathy Liknes and their five-year-old grandson Nathan O’Brien.

The two positions—reporting crime and being the brother of a victim of crime—carry uncommon burdens, including the peculiar yet familiar circumstances of being exhibited in the public square. And so I tried to do what journalists do: curb my emotions, especially when reporting the most disturbing subject matter. For the most part I was successful. But the sights of the courtroom are homogenous with both time periods, from the lawyers’ robes to the wooden benches.

While I’ve covered court cases before, the Garland trial was unlike any assignment in my past. Perhaps that’s why some readers expressed gratitude for the service, while simultaneously asking how I can cope with reporting such horrible content. As someone who knows the pain of the impact of violence, this process sometimes includes flashbacks to darker times. For myself, I’ve learned the answer is three-pronged: duty, perspective and necessity.

It is my duty in that this is what I signed up for. That doesn’t mean I’m exempt from being sensitive—in fact, it’s quite the opposite. Finding humanity is imperative to our craft, preventing us from becoming too jaded with the material we cover. But at a certain point, journalists often develop an occupational adaptability of dealing with sometimes sinister stories, while still needing to consider the visceral effects on the public.

And so perspective is needed. I was reminded that no matter my mental condition over the course of the trial, it paled in comparison to that of the Liknes and O’Brien families and their friends. My feelings were trivial compared to theirs. I even found solace in the professionals who have dedicated themselves to the pursuit of justice and truth, from the police and lawyers to the jury and judge. If they can sit every day in that courtroom, I thought, I certainly could too.

Which leads me to the necessity of dealing with trauma. It was a reminder echoed from the judge in the case, David Gates, who often addressed and safeguarded the jury over the course of the trial. At one point, he instructed them not to block out emotion, but to acknowledge, discuss and harness it. He told them not to block out others, but rather to accept, embrace and find comfort in them.

We often have no control in distress we encounter; there’s often no rhyme or reason for the rampant form that pain may take. In the courtroom context, I have no choice but to acknowledge graphic evidence that illuminates the worst thoughts and behaviours that come from the human condition. My own near emotional breaking point came late in the Garland trial, when the Crown showed a small, bloody handprint on a wall as part of the evidence. I thought of my young daughter; I nearly cried in the courtroom. As the relative of a victim, as a journalist and now as a parent, confronting those pains emphasizes the fragility of life. Anyone is susceptible to cruelty and suffering of the most awful degree. Sadly, too many of us have come to terms with that reality in the most heartbreaking of ways, however vital it must be.

That’s why I’ve written about these two parallel experiences. I can’t dismiss the emotions I felt at the trial, or from those when I think about Yancy. After all, only we can determine how much emotion we hold in and give out. I’ve learned that whether you’re a journalist reporting on horrible acts or you’re someone whose life has been affected by horrible acts, there’s solace in the outpouring of support of family, friends and peers, like a blanket that warms you from a stinging wind. The hard, necessary task is letting yourself feel that emotion, to reveal how precious life truly is and that the pursuit to live it fully, with all its inherent possible hazards, is one worth engaging.

That was my way forward years ago when the world and I lost my brother. One difficult trial later, seen through the eyes of a journalist, that is my way forward still.

Lucas Meyer is a reporter and producer at 660 News in Calgary and a contributor for Sportsnet.