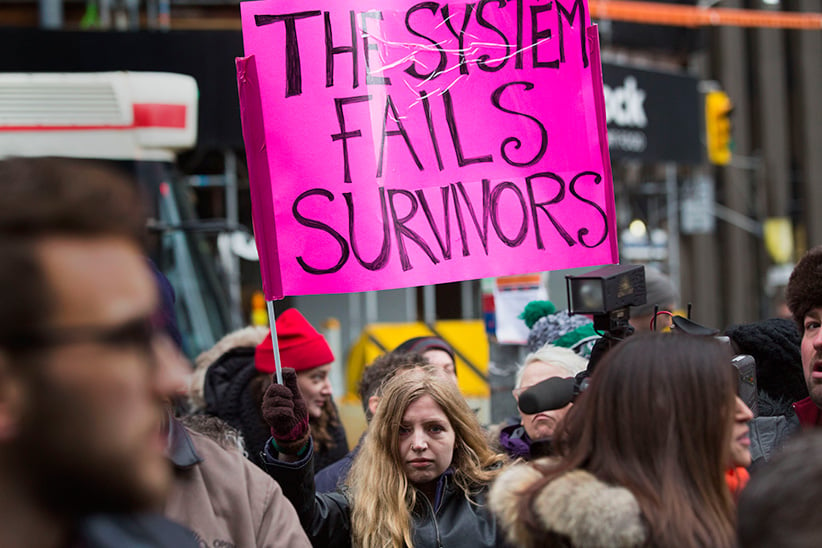

Kathryn Borel: ‘It was death by a thousand cuts, that’s how it felt’

Read a transcript of Jian Ghomeshi accuser Kathryn Borel’s long, exclusive conversation with Maclean’s

Share

Maclean’s reporter Anne Kingston, who followed the Jian Ghomeshi trial every step of the way, spoke to former CBC Radio producer Kathryn Borel, who brought one charge of sexual assault against the former host of the CBC Radio show, Q. The charge was withdrawn after Ghomeshi agreed to read a public apology to Borel. Read a full transcript of her conversation with Kingston as she tells us what happened in the Ghomeshi incident, why it was a “climate of abuse,” why she won’t seek a civil trial against the CBC for an apology from the public broadcaster, and why she didn’t initially understand that Ghomeshi’s actions constituted sexual assault.

Anne Kingston: Kathryn Borel joins me now.

What was it like sitting in court, listening to Jian Ghomeshi publicly apologize to you?

Kathryn Borel: I think the main thing on my mind was actually a logistical issue, because although I had asked the Crown, and my lawyer, Sue Chapman—who’s terrific—as many preliminary questions as I could in order to prepare myself for this day, I hadn’t asked them, “is he going to be facing me, or is he going to be facing the judge?” I didn’t know who he was going to be delivering the apology to, and there was a moment where he did a small, super tiny, wasn’t even a quarter turn, but [he] kind of turned slightly in my direction, and I was sitting next to my mom and I can’t remember who grabbed whose hand first, but suddenly my mom and I were holding each other’s hands, because I was worried that he was going to look at me, for some reason I just didn’t want him to look at me, I wanted him to look at the judge when he was delivering the apology.

AK: That’s interesting you say that because you know, technically an apology is a delivery of remorse to someone, and in a way the delivery was toward [you]— his back was literally to the gallery, a bit to your side to where you were sitting in court.

KB: So when I was told about the specifics of the apology, and I wasn’t privy to the final draft of the statement—Michael Callaghan—the Crown, Jamie Klukach, also Crown prosecutor Sue Chapman who was my lawyer, they were all really good about being transparent and bringing me into the process, but obviously, sort of at the end, it was privy to privilege, or it was subject to privilege, and I didn’t see the final draft of the apology. But I knew that certain principles that we had laid out to Ghomeshi’s team, to Marie Henein, had been met. What I had gleaned from the things that I had heard from my lawyer, Sue, was that it wasn’t going to be as rigorous as we hoped for, because we had drafted—the Crown had drafted—an initial draft of the apology that was a really scathing indictment of what he did.

AK: And that was written by Michael Callaghan?

KB: And that was written by the Crown, and parts of that were shared with me, and there were a couple little amendments that I had made just to correct, I guess, the tone. At one point the apology addressed me as “you” in the second person instead of “her” in the third person, and for some reason I didn’t want him referring to me in the second person. The reason for that is because I wasn’t sure if his apology was going to be genuine, I wasn’t sure if it was going to come from the heart. Because this was a deal that was brought to us by the Henein team, and I don’t think that it was Ghomeshi’s idea. I knew that we were going to get some kind of admission—not in the legal sense, but some kind of admission that this had happened to me, that there had been an incident of physical touching—I knew he wasn’t going to get into the specifics of what the charge was, because I had been told that by my lawyer through the Crown. So, in that moment where he was possibly going to turn and deliver the apology to me, I didn’t want to look him in the eyes, because I didn’t think that it was going to be fully genuine… if that makes any sense.

AK: Well, there are a couple of things that are apparent from that statement. One, there was a sense that you really didn’t want any personal interaction with him, the sense of him looking at you or even speaking to you directly. Was that… is that almost a visceral thing, do you think?

KB: I think so. I think that… I worked for him for three years, he debased me for three years—I’m still feeling the consequences of that debasement, to be honest. I think that when I saw him in court, I… I know the word trauma has been…we’ve been talking a lot about trauma and it’s a big word, but I do believe that I was traumatized by him over the course of those three years. And so the idea of him—my abuser—looking at me in the eye while he was apologizing to me, in what was perhaps not quite a genuine apology because it was structured in the judicial system, worried me. I just worried what effect it was going to have on me.

AK: So, you had not seen him, then, since you left Q, in 2010?

KB: I, actually, no, I had seen him once. So, a year after I left the country—so it was 2011, I was living in Los Angeles, and I think he had just gotten his book deal for that book that he wrote, and he contacted me over Facebook. And he said, “hey, I wanna talk to you about this book that I’m writing, and I would love your advice on what it’s like to write a book”—because I had written a book, it had been published a year before. I talked to my parents about whether I should meet him, I talked to my boyfriend at the time about whether I should meet him, I talked to friends, because I was like “I don’t want to go.” While I didn’t feel like I was still under his thumb, I also felt like he was still a very powerful man in Canada, and if I ever needed to go back—what if I needed something from him? And so I went to the Sunset Marquee, which is a hotel in west Hollywood, and we met by the pool, and within minutes of us sitting there, he said “is it all right if I take off my shirt?” And I was like, “…I guess so?” And so he took his shirt off and then lay there, bare-chested, as we had a drink. And I had a drink, and I got out of there as fast as I could, and knew, obviously, that I had made a mistake in going there.

AK: Were you able to even process what he was saying, the actual words he was saying in court yesterday? I want to talk to you specifically a bit about those words, but were you actually able to digest?

KB: I didn’t process the statement as a whole, I think I processed the parts of the statement that bumped for me. And the part that I immediately think of right now that bumped for me was when he referred to our friendship—I can’t remember exactly the wording of it.

AK: I can tell you.

KB: Okay.

AK: He said he didn’t realize he was being inappropriate, and suggested he thought it was okay, because this was a creative environment, and there was “an office friendship” with you.

KB: Right. And it’s funny, hearing that read again, I didn’t even pick up on the “creative environment” part, I think I was blacking out a little bit during the apology, because it was a pretty surreal experience. And again, that shocks me, right—because it was a “creative environment” it was okay that he bends me over a desk and touches me in the way that he did? I work in Los Angeles now, I’ve been in writer’s room[s] which have been very male-dominated [and] I’ve never been bent over a desk, I’ve never had my butt grabbed, I’ve never been told by one of my male colleagues that he wants to hate-f–k me. So that to me is nuts. And then, as for the office friendship, we weren’t friends. We never went out, one-on-one, and had a drink; I never set foot in his house for a Christmas party… he was mean to me all the time, you know, you’re not mean to your friends, even with your office friends. I have friends, I have office friendships from Q. Jian Ghomeshi wasn’t my friend, I was… he was in a power position over me at all times, and a friendship to me is a democratic relationship where both parties are equal. We weren’t equals, we were never equals, and he took every opportunity to remind me of that.

AK: What was interesting about sitting in court, and then your statement after, was the different versions of events, the way they were portrayed. For instance, the term sexual assault was never used by Marie Henein —

KB: —by him.

AK: —Or Jian Ghomeshi. In his apology to you, he talked instead about being sexually inappropriate, which is a lesser… is non-criminal, obviously. But your statement outside was strongly worded and unequivocal. You said, “he violated me in ways that violate the law.” How important was it to you to make very clear to the public that you were not accepting that this was anything less than criminal behaviour?

KB: It was literally the only reason I took the deal, [it] was to have an admission on his part. And while that admission had to be built through pieces of information that were revealed in court… so what I knew was that Michael Callaghan was going to get up in front of the judge, discuss the terms of the 810 peace bond, and say in text what the charge was, which was the incident that we now all know about, bending me over the desk and pretending to have sex with me from behind while fully clothed—which is a physical violation, which is sexual assault. So I knew that Michael Callaghan was going to do that, and I knew that Jian Ghomeshi was going to talk about some incident of physical touching. But through the building of those two parts, that built sexual assault, an admission of sexual assault for me. Obviously not a court admission, but an admission to people who exist outside of the court, which is basically all of us, that this is what he did to me. I needed to make sure, that when I was out on those courthouse steps, to remind everyone of what the incident was, and to remind everyone that that incident was criminal, and that criminal charges were brought against this man. And to go through the trial—which, again, I was fully prepared to do, but it felt more significant for this person, Jian Ghomeshi, who had fallen silent for 18 months and not said anything publicly, after he had made claims that he was going to fight all these allegations in court, he was going to address all of them head-on, and that everyone was lying, and then that he went quiet afterwards, I felt it was really important—optically, and to me and hopefully to other people—to send a message that he did this. And that he said it, he had to say it. And sure he used vaguer terms, but he said it.

AK: I wanted to talk to you also about the whole idea about not understanding it was sexual assault. One of the points you made on the court steps, or just before [at] old City Hall, was that, you said that “until recently, I didn’t even internalize that what he was doing to my body was sexual assault.” And I think that’s one of the interesting aspects of this whole trial—Lucy DeCoutere said that she didn’t know that what she alleged Ghomeshi did was sexual assault, she thought she had to be raped and beaten. I’m just curious to know when you realized, how did you come to the realization that that behaviour constituted sexual assault?

KB: When the cops told me. So what happened was, I was preparing to come out of anonymity after being part of the journalistic investigation, because my story was coming out in bits and pieces in the news, and I felt like it was important to put my name and face on what had happened to me, because I first of all was no longer scared—I was still scared but I wasn’t as scared as before—and second of all I felt like there was a real opportunity to add more specific language and vocabulary to the issue of sexual assault which we really only just started to talk about in a meaningful way, I feel, in the last few years. Because of Ghomeshi, because of Cosby, because of Jimmy Savile, because of these really high-profile people who commit serial assault. And so, because that language architecture currently is so… or it’s becoming less brittle but it has been brittle in the past, I didn’t know. Also, I didn’t know, because every time I turned to someone for help, in people who were in positions of authority at the CBC—my executive producer, the guy who I went to at the union—at every turn, people were telling me to just swallow it, to just deal with it. And in one case, I was told that it was my fault, it was that I was provoking his advances. So, when you’re told by many people at your national institution that it’s “just some office flirting, don’t even worry about it, just, like, you’ve got to figure out how to modify your behaviour,” how in the world could I have known that it was sexual assault? So it was only until I came out of anonymity to say my piece, and then as I was doing that I thought maybe I should give the cops a call, to see if I could be of help to them in any way, and Ali Ansari from the Toronto Police, who’s terrific, said, “Kathryn, that’s sexual assault.” And I was like, “No, I’m not a victim of sexual assault.” And he said, “If someone did that to you on the subway, some stranger, what would you think that would be?” And I was like, “Sexual assault.”

AK: But in the workplace…

KB: But in the workplace, and because he was so institutionally protected, and because no one was allowed to stand up to him without being punished, I didn’t know. And because, because he was a celebrity, and because of so many other factors that shouldn’t come into play but that did come into play within that context.

AK: During your statement this week, you talked about, you expanded the terms—the case in question was dating to February of 2008, but you talked about every day for three years having to endure certain types of behaviour. Were you talking about… you were talking about a climate of abuse, generally, when you made that statement?

KB: I was talking about a climate of abuse that began before I was even hired on that show, a climate of abuse that began in 2006 when he approached me after hearing a piece that I had done on Metro Morning that he had liked, and he approached me, he emailed me and said, “I liked your piece, can we meet for coffee.” I met him for coffee, he made an off-colour comment about the tightness of my tank-top, which I brushed off because if any woman was to get outraged every time a man made a comment about a piece of clothing [she was] wearing, [she’d] just be screaming all day, every day. He approached me, he said, “I’d really like to help you get this job, I’m going to have this national arts and culture program, you’d be a great fit” and right after my interview—which went well, except I flubbed one question. He had entreated me, he had said, “You can call me or email me after your interview and I’ll give you as much information as I have about how well you did.” So after I had flubbed that question, I decided to take him up on his offer, and so I emailed him: “Did I do okay, I’m not sure if I did okay, I flubbed this one question, I hope I didn’t blow it.” He emailed me right back and he said “We’re going to go in a different direction; better luck next time.” And it was so off-handed, and it felt so brief and a little cruel that I was confused, because the tone had been “I’m going to help you! I’m going to help you get this job.” It wasn’t until I think almost 24 hours later that he wrote—and I had called him, and I had texted him, and I was like “Hey, are you kidding, I don’t know if this is a prank, I’m starting to feel really bad and insecure and confused and you told me that I could call you for help and for information, and anyway, if you could clarify this, that would be great”—and it wasn’t until the next day, after I had really been doubting myself and feeling bad that he said, “Oh, no, no, I was just kidding around.”

Related: Jian Ghomeshi’s trial ends—and so begins his bid for redemption?

AK: Recently, the National Post ran a story in which two other women came forward to say that they had experienced similar behaviour. Did you think at the time that you were alone experiencing this?

KB: I knew I wasn’t alone because all of my other colleagues were also being abused by him in different ways. He seemed to reserve the sexual stuff, at least at Q, he seemed to be reserving the sexual stuff for me, for whatever reason, I don’t know why. But everyone had their own tailor-made abuse that was based on their own insecurities, their fears. He was really good at getting to the soft belly of who you are and sort of attacking that spot. He was really good at playing people off each other. My colleague Tori and I—her nickname that Jian gave her was T-Bird and mine was K-Bo—and sometimes he would play us off each other, so he would be really, really nice to Tori one week, and then he would freeze me out that same week. Then the tables would turn and suddenly I would be the favourite and then Tori would be out in the cold. And the way that he would demonstrate that beyond just his office behaviour was in the credits on Fridays, when we would run the credits and he would say the list of producers who worked on the show, he would give everyone, you know, “thanks to Tori T-Bird Allen, thanks to Kathryn K-Bo Borel.” And if he was displeased with you, he would leave out your nickname, as a little punctuation mark on your…

AK: So it sounds like you were on a psychological hamster wheel.

KB: All the time. All the time. And so when I was talking about—in my statement yesterday—how it was everyday abuse, it was… it was death by a thousand cuts, that’s how it felt.

AK: In court this week, the judge said that you had “significant input into the resolution and the way it played out.” Could you walk us through how that happened? Let’s go back to when you first realized there could possibly be this kind of resolution forward.

KB: Right. So, a little bit of background context here: in mid-March, I got a call from my lawyer, Sue, and then in mid-April, I was flying to visit my grandmother, and on a lay-over in Salt Lake City, I actually had a call planned with the Crown because I just wanted to talk about what evidence was going to be presented, what I was going to be expected to say in direct testimony, I wanted to know maybe what Marie Henein’s tactic was going to be, in terms of dismantling my credibility on the stand because I figured that was probably coming, considering what had happened in the February trial. I just wanted to have a chat with the Crown, and they’d been great the whole time, so we set up the phone call. As I started to say, “Hey, when am I coming, what’s the day that I’m arriving?” Michael Callaghan said, “Actually, there’s a new deal on the table that’s come from the Henein side, and it’s this: it is an 810 peace bond”— and then he described to me what that was, and then he said, “it comes with an apology.” We all had a conversation—I feel really grateful that they included me in the conversation to the extent that they did—about resolutions that were in the public’s best interest. Sometimes, what is in the public’s best interest, and what is in the complainant’s best interest, especially in cases of sexual assault, doesn’t necessarily happen in the court room. We started talking about how powerful it would be to have him open his mouth for the first time after 18 months of not speaking and denying all these charges, [and] for the first words out of his mouth to be “I did this to Kathryn Borel.” We didn’t accept the deal; we then started talking about what the wording of the apology was going to be, and essentially, we didn’t accept the deal until Monday, because Michael Callaghan drafted—

AK: Sorry, just to put it in the context, we’re talking Monday, two days before?

KB: Two days before, one day before I was expected to fly out. So, we started talking about this apology. Michael Callaghan and Jamie Klukach started drafting the apology; it came into me, I want to say a week and a half after we had that conversation, possibly early May… I can’t remember how long it took, but it took, you know, a week and half, maybe two weeks for them to draft it. My lawyer called me, and because I couldn’t actually have the physical copy because that was subject to privilege, Sue gave me the broad brushstrokes about what was going to be in the apology, and it was really strongly worded. I was like, “this sounds great.” She said, “We’re not going to get all of this, but we’re going to be the first ones out of the gate in terms of the strength, and then they can come back to us with obviously what’s going to be a diluted version, and we’ll just go back and forth, because it’s a negotiation, we’re going to go back and forth until we get it right.” So we didn’t get their revision of our original text until Friday, so the Friday before my Wednesday court date, which was the 11th, four days before, we finally got the revision. I just want to say, revising the text—I think it was a hundred-word text, that takes an hour. Henein’s team really… we went up to the wall in terms of waiting for them to come back at us with a revision. When we got the revision of that statement from the Henein team, it was… there was not enough red pen in the world to mark it up and say no way, we’re not going to accept this. Sue was very circumspect, she said “I don’t even want to read you what it says, because you’re going to go crazy.” I said, “Give me the highlights, like, give me the highlight reel, obviously.” She said, “There’s a very long portion where he goes into grave detail about how much this has cost his mother and sister emotionally, and there is a portion which says that you acted in a jocular manner.” And I said, “Okay, so he’s victim-blaming me in the apology.” We had a very long conversation where I definitely did a lot of yelling, and she said, “Don’t worry, we’re going to get this right.” But, at that point, I was like, “let’s go to trial, forget it; if this is what’s happening, forget it.” She said, “Absolutely, and we are, we’re ready to do the trial if we don’t get this right.” So, I guess the Crown went back to Henein and said you have until Tuesday morning—and I was supposed to fly out Tuesday afternoon—you have until Tuesday morning to come correct, and write the text that we agreed to in principle. They came at us on Monday morning, 24 hours before their deadline, and we had a text that we could work with.

AK: You alluded to the first trial, in which the witnesses were all cross-examined with extreme vigour and their emails were exhumed and so forth. What role did that play in your thinking about wanting to go to trial, or how did it influence your decision to, you know, take part in this resolution?

KB: Two things. One, I felt so badly for those women. It was unfair. I know that it’s court procedure, I know that everything was technically fair, but the way in which their credibility was dismantled, the thing that really bothered me was that it seemed as though the primary strategy of defence was really relying on rape mythology, and how to be the perfect victim after you’ve been assaulted, which, as we now know, victims act in very counterintuitive manners after they have been assaulted. So, I had a lot of sadness for the way that all rolled out. Part of me felt incredible defiance, that I wanted to go to trial so that I could get the conviction. Again, you know, it’s not me getting the conviction, it’s the Crown, right, so, I started personalizing it in a way I think that probably was not so healthy. So, in a way it strengthened my resolve, because I wanted to go fight her, I wanted to go fight him and her, I wanted to do it. Obviously, because I am a human being, I was also scared of what she was going to drudge up, what had I forgotten. I was pretty sure I hadn’t forgotten anything. Also, the factual context was so different than the first trial, because it all happened at work, I never was romantically entangled with him, I never set foot inside his house, even for a Christmas party, so it was different, so even though I didn’t love watching what happened in February, it felt like apples and oranges a little bit, because the factual context was different in mine.

AK: There was much discussion about the different context of the first and second trials. The first trial was sort of [about situations that were] dating, romantic; this was professional. There was also talk about the fact that the two of you were fully clothed, that it was, you know, just rudeness but not necessarily serious, and something that would have long-lasting ramifications. Could you speak to that?

KB: Sure. I think that what has been interesting about this process is that moment you sort of submit your body to the judicial process, after an assault has happened, which happens to a person’s body, like, it happened to my physical [body], on a cellular level I was assaulted. Suddenly, when you flip yourself over to the cops, and then the cops flip you over to the Crown, and the Crown takes your case, it starts to become further and further removed from where the actual crime happened, which was my body. That kind of abstraction and that kind of objective language that suddenly takes over from a very subjective experience, that’s what goes out into the media, and that’s what is analyzed by people, it’s not me saying, “hey everyone, I got really hurt,” it’s now the cops talking about it, and the Crown talking about it, and the defence talking about it, and that being interpreted by the media, and people on Twitter and people on Facebook, and that’s a strange thing. Because that assault that happened to me—and you know, it wasn’t just the charge, there were a few other times of physical touching. I’ve experienced assault in other contexts that are more dramatic, and what I realized in the other specific time that I was assaulted—which happened after my time at Q, where it was proven in the courts in Los Angeles that an attack had happened and the person who did it to me went to jail—it was not dissimilar, you know, these two experiences were not dissimilar in terms of how they made me feel. People who want to minimize or interpret damage that is done to someone else’s body, because it was clothed, because it wasn’t penetrative, I think they don’t know what they’re talking about. I think that assault is assault. Also, you know, it happened over the course of three years, and there was a psychological component, and an emotional component. I hope this is not too egregious of an example, but when you live in fear for three years that you might be attacked, that takes a lot of a person, that takes a lot of energy out of a person. If someone was to hold a gun to your head for three years and say, “I’m going to shoot, I’m going to shoot, I’m going to shoot, I’m going to shoot,” that’s hard. So, when the physical assault took place, because there was suddenly empirical evidence that a physical assault could take place in my work place, just because it didn’t happen every day, and just because it was clothed, doesn’t make it any less of a violation, and doesn’t mean that I didn’t live in fear that it could happen again to me at any point. That was the experience of being at Q—was that this man, at any point, could do this to me again, and he could start doing it with greater frequency, and he could start doing it with greater aggression. What was to stop him from, if he grabbed my ass in the studio, which he did also in February of 2008 in a soundproof area, what if the next time what he wanted to do was try to tongue kiss me, was to try to punch me and grab my boob? Like, that’s what fear is, that’s what was happening, and so to minimize that because I was wearing pants, is really missing the point.

AK: Jian Ghomeshi wasn’t the only person who apologized to you this week. Hours after his apology in court, Chuck Thompson, who’s the head of public affairs for CBC, went on As It Happens to issue a public apology. He was interviewed by Carol Off. Was that something that you expected?

KB: No. I actually saw your tweet, and so I went to listen to it. Chuck Thompson has hedged a lot in these 18 months, so I was surprised to hear him, very uncomfortable, as Carol Off really laid into him yesterday. That was surprising to me. However, I think you said something about Chuck Thompson apologizing to me, and I’m not sure I heard the words, “I’m sorry, Kathryn Borel.”

AK: Well, those are words you also did not hear in court earlier, but as you say, Carol Off was pretty tough with him, and she asked whether the apology was prompted by the concern that you might sue the CBC. His response was “that’s a question that is best answered by Kathryn Borel.” Well, Kathryn Borel, what’s the answer?

KB: I don’t have a lot of energy right now. This has been a really hard 18 months, just preparing. I have a really demanding job in Los Angeles, too, I usually have a few projects going at a time, so, you know, and I have a life, and I have friends, and I like to play tennis, and I like to go on bike rides, and so I have a limited resource of energy when it comes to this particular subject. At this point, although I would really love an apology, a straight out “we’re sorry that we created and promoted an environment that hurt you so much”—I would love to hear Hubert Lacroix say that, I would love to hear Heather Conway say that, I would love to hear Chuck Thompson say it, just in a sentence, you know, in a strung together sentence, without Carol Off bullying him into saying it. I would love for the people who at the beginning of this process called me a liar to say that they were wrong. You know, those words are still out there, no one has formally withdrawn the fact that there were people at the CBC who were calling me a liar when I first came out as a source in the media story. No one’s formally withdrawn that. So yeah, I’d love an apology. I would love to get it without doing a civil trial; I would love for them to have the common decency to give me my apology.

AK: Is that something you’re considering?

KB: At this point, I don’t have the energy for a civil trial. And I don’t have the energy for people coming out of the woodwork and saying, “Here it is, here’s Kathryn, she’s doing it in civil [court], she wants the money now.” I don’t have the energy to have anyone question what motivated me to come out and actually participate in the judicial process, which was really just [because] I wanted to tell the truth about what happened to me.

AK: The Ghomeshi case has highlighted the disconnect between the court of public opinion and the court of law. In front of court yesterday, you said that agreeing to a peace bond “seemed like the clearest path to the truth.” Now that’s a true indictment of the legal system. You said that, “the trial would have maintained his lie, the lie that he was not guilty, and would have farther subjected me to the very same pattern of abuse that I am currently trying to stop.” What makes you convinced that there will be no truth found in the legal process?

KB: I didn’t say that there would be no truth, I said that this seemed like the clearest path to the truth. I think that truth can be found within the judicial process, obviously. But I think as you said, the chances of finding it in sexual assault cases because the burden of proof is so high, there’s just a much lower rate of conviction; we all know the numbers by now, it’s a much lower rate of conviction. That’s why people don’t come forward, it’s because at every turn you are doubted, and you are questioned, and you are told that you are liar, and you are told that you are out for fame, or out for money, at every turn there is a disincentive to participate in the legal process. I wanted to participate in the legal process, that’s why I came forward, but sometimes there are greater truths than what can be found in court. And I kept thinking—I’m about to enter, if I go to trial, I’m going to enter Marie Henein’s house, and her house has way different rules than my house, which is outside the courtroom, has. Those rules are fine, those rules were put there for a reason, and sometimes they work, but for sexual assault victims, they don’t work a lot of the time. I really like this quote by Jon Krakauer, you know, he wrote this book on campus rape called Missoula, and he talks about how sexual assault is a crime like any other, except in every other crime, the victim is not assumed to be lying. That for me is a big disincentive. For me it wasn’t—I was ready to go to trial—but I can understand how that would be a disincentive for a lot of people. So again, I believe that it can work, it worked for me in California four years ago, but in this case, because there was a very highly paid lawyer, because we were dealing with a celebrity, because we were dealing with extenuating circumstances that were beyond just the facts of what happened, this seemed like the clearest path to the truth.

AK: You talked earlier a bit about feeling like public property as this case commenced, and it was an incredibly unique case in the sense of celebrity factor that is associated with it, but can we talk a bit about that process for you, in terms of the longer narrative, and the fact that you were under publication ban, which everyone sort of knew who you were. How did you feel about being protected by publication ban, was that something that helped you through it?

KB: It did, it helped me because I needed to still go to work, I still needed to make money, I still needed to get groceries on the table, I needed to take care of my poodle, and the idea that my name would be out there, because I am a sensitive person, and because I know how mean people can be when it comes to victims of sexual assault, I didn’t want that in my day-to-day life. I already had enough stress with the trial coming up in my day-to-day life, I didn’t think that adding my name to it at that point was something I could really handle, just in terms of my own stress levels and being able to sleep at night, and being able to wake up in the morning with the energy to actually go about my day. Yeah.

AK: One thing that people who work in the field of sexual assault—lawyers, counsellors—say that what victims of sexual assault want is to be heard, and believed, and recognized. And there’s not really a place in our court system, that’s not something that’s valued. The resolution that you reached this week allowed that to happen to a certain extent, and it is also is one in which everyone is walking away saying, everyone can say a certain amount of victory, you know, Ghomeshi’s team can say they—

KB: Negotiated.

AK: They negotiated it, he doesn’t face trial; you got to hear an apology. Do you feel like you were heard?

KB: I do feel like I was heard. I didn’t know I was going to be heard when I was writing my statement, and rewriting it and rewriting it, I had no idea what impact it was going to have, but I mean, I woke up this morning, and I was on the cover of two newspapers, there were five photos of me throughout the Toronto Star today with really warm, thoughtful articles about what had happened. And not just about me, but thoughtful articles about where we’re at in terms of dealing with the catastrophic problem that is sexual assault. That’s a huge win, just to productively move forward this conversation, which is so hard to have because there’s so much shame in it—when there shouldn’t be, but there is—when there [are] so many taboos, and there’s so much discomfort when it comes to talking about it, to suddenly kind of see it in the newspapers and see it on websites and see it on Twitter, it being talked about, and sort of that pall of shame, at least for today and I think yesterday as well, to see that be really lifted in a concrete way, that was huge. I think that’s something that everyone should be really happy about.

AK: At what point yesterday, on Twitter, after the trial ended, you were trending, you know, your #Borel was trending above #Ghomeshi. I don’t know what that signifies, but certainly I think it signifies an appetite to have the kind of conversation that you’re talking about.

KB: Yeah. I think that’s true. I think it probably is also I’d just come out from under the publication ban, so people were probably talking about me just because my name had been put forward in the public sphere for the first time with regards to this case, and his name has been in the press a lot as well; I don’t know the metrics about why I trended higher than him, but I hope it signifies something good.

AK: There’s also the inevitable response that Ghomeshi is getting away with it, there’s a sense that your case was a strong one, in the sense that there was a witness, there was a paper trail, and you know, given the fact that the Henein side was very clearly motivated to come to some sort of a resolution also speaks to that. What do you say to people that express frustration and remorse that he “got away with it”?

KB: I don’t know what to say, because I don’t think that he got away with it.

AK: Well, that I guess is a wrap. Thanks very much.

KB: Thanks, Anne.