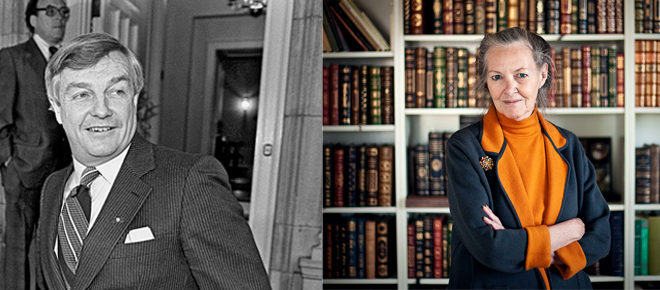

Knockin’ on doors with Peter Lougheed

Elaine McCoy, the last Progressive Conservative in the Senate, remembers the former Alberta premier

Share

Progressive Conservative senator Elaine McCoy remains a Progressive Conservative to this day, in large part because of former Alberta premier Peter Lougheed.

“There was an honesty and a decency to Peter Lougheed, and certainly in the way he conducted himself,” McCoy says from her home in Calgary. “Before he was elected–and in fact I have that document–they had made up rules for themselves on how to behave, and the one that strikes me so powerfully these days is ‘never attack the person; only attack an idea.’ That’s a message or a policy or a practice that is just not being honoured these days. I think people need to be reminded of it.”

McCoy first met Lougheed when she moved into his riding, around 1980, and volunteered with his constituency association.

“That was my first memory of him being my MLA, and watching him looking after his constituency,” McCoy says. “I didn’t realise it then quite so much, but he was an example of all of his MLAs. He never forgot his responsibility as an elected representative. He would do things like hold town hall meetings at least twice a year; he’d go door knocking twice a year. Of course he had an annual meeting, he regularly met with his constituency board. He was on top of it all the time.”

McCoy ran to replace Lougheed in the provincial riding of Calgary West after he announced his resignation. As someone who had been chosen to go door knocking with Lougheed on a few occasions, she had apparently impressed him.

“He said to me ‘I’d like you to consider running next time,’ and my response to him was ‘oh no, Peter. You can’t leave – we need you’,” McCoy recalls. “And he said ‘No, no – I would have left last term, but I couldn’t leave in the middle of the NEP debates,’ and he said ‘it’s time – nobody should hang around too long’.”

“That’s what he told me – ‘I think you’d work hard, and you would work for the people of Calgary West and Alberta.’ So then I thought about it,” McCoy says.

After deciding that she could go from a lawyer’s salary to that of a backbencher, she ran and won, and was surprised to have immediately been made cabinet minister in Don Getty’s government, especially considering that she didn’t really know Getty or anyone in the party hierarchy. Later, when Getty resigned, McCoy ran in the leadership race to replace him.

“I was very policy oriented,” McCoy says. “I had a plan to get the province out of debt – it was called the McCoy Plan, and that would have been something I would have learned from Peter – think through what you’re going to do. He always used to say people will vote for something, not against something, and so I had something for people to vote for. They didn’t, but I had something for people to vote for.”

McCoy lost to Ralph Klein in the leadership, and in 2005 was appointed to the Senate by Paul Martin as a Progressive Conservative. She is the last representative of that party on the federal stage, where she still carries forward the Lougheed’s legacy to Ottawa.

“Peter declared, and proudly so right from the get-go, that his would be an activist government,” McCoy says. “He strongly believed that the government has a role. He totally believed that the private sector had a major role, as of course did the not-for-profit sector, but the government was there to help.”

As an example, she recalls going door-knocking with Lougheed at a time of severe recession, and when mortgage rates were in the mid-teens at the time of stagflation.

“Door after door after door, what I was hearing and feeling, and so was he, was fear – fear for their future,” McCoy says. “He went back to Edmonton, and within two or three weeks, he announced a new program, which was a mortgage relief program. So the government issued cheques to people to help them pay their mortgages. He saw that need and he stepped in, and that was his view of what governments should do to help.”

And while it did mean the government took on more debt at a time when royalties were down, it was because Lougheed also understood that governments could weather those downturns better than individuals could.

McCoy has no trouble listing some of Lougheed’s other long-term investments – the grain hoppers the government bought because the railways didn’t have enough to get the province’s crops to tide water; the research and development that led to the exploitation of the oil sands; and the establishment of the petro-chemical industry in the province.

“He took risks,” McCoy says. “But they were well-considered risks.”