Of rape and justice

From the 1998:Seven months after Maclean’s investigation into rape in the military, the magazine asked if anything had really changed in the Canadian Forces?

Share

This story was originally published in Maclean’s December 14, 1998 issue:

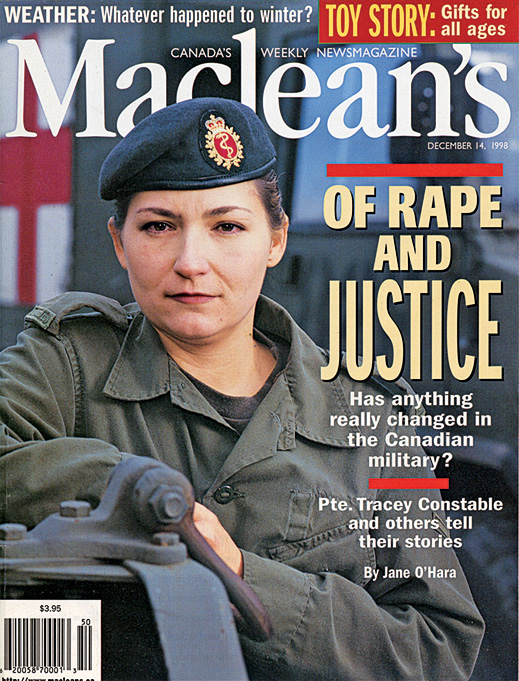

Tracey Constable was understandably skeptical when, last May, Canada’s top soldier, chief of defence staff Gen. Maurice Baril, called on women who had been sexually assaulted in the Canadian Forces to come forward and tell their stories. Constable, a native of Grand Falls, Nfld., was one of those women. Eleven years ago, she says, as a 22-year-old medical assistant in the air force, she was raped by a military doctor, a captain, on the seventh floor of the National Defence Medical Centre in Ottawa. She did not report the attack at the time, feeling she would not be believed by the military brass or by a system that often favored rank over reason. “Being a private and being a female,” she says with a strong Newfoundland accent, “I knew no one would even listen to me.” Instead, Constable left the Forces with her secret, abandoning the career she loved.

For more than a decade, Constable says, she “rehearsed in my mind a thousand times” how to tell someone what had happened to her. But she kept silent—until last spring, when she picked up the May 25 issue of Maclean’s and cried as she read the heartbreaking stories of women who claimed they had been sexually assaulted by military men. Constable stepped forward, contacting Maclean’s with her story (it was published in the June 1 issue). And in spite of her skepticism, she also welcomed the opportunity to finally pursue her case within the military, especially after Baril, under pressure to act, issued his unprecedented invitation. Now, with her allegations in the hands of the Ottawa Crown attorney’s office—the case no longer falls under military jurisdiction—Constable says she has few regrets. “I’m glad it’s come this far,” says Constable, who is still a reserve private and works on contract for the military as an administrative assistant.

Related:

Rape in the military

Speaking out on sexual assault in the military

She is one of the lucky ones. Of the more than 30 women who came forward to Maclean’s with their stories of sexual abuse in the Forces, almost all have been disappointed with the military’s handling of their cases. Others who contacted the Forces, either through Baril’s office or the special 1-800 sexual-assault hotline established when the news reports appeared, also express regrets. In some instances, they say, bungling has marred the investigations, which Baril promised would be thorough and handled by the new National Investigation Service instead of the vilified military police. In others, the difficulties of reopening a case after many years have presented insurmountable obstacles. And, almost always, there is the heartbreak of reliving a tragic episode in their lives. In all too many instances, it appears, the search for justice has proven almost as painful as the incident that prompted it.

When Baril, in the wake of the Maclean’s reports, admitted the Forces had a problem integrating women into the ranks and declared that sexually abusive behaviour would not be tolerated, Constable jumped at the chance to talk to the chief of defence staff. “He said he wanted to hear from us, so I said, ‘OK, he’s going to hear from me,’” says Constable, who was also one of more than 75 people to call the 1-800 number as of the end of October. “He was pretty vague when I talked to him, almost like he was reading off a sheet of paper. But I was also proud of him for finally sticking up for us.”

More important, her allegations against the doctor, who is out of the Forces and practising medicine in Wisconsin, were actively pursued by the NIS. Now, after a five-month investigation, it is up to the Crown to decide if there is enough evidence to lay charges. “It’s been hard waiting,” Constable says. “I know I’ll be scared if they lay charges—scared for my life. But I’ll be happy, too.”

Lesleyanne Ryan, 33, a Forces administrative clerk, says the military turned its back on her when she reported being sexually assaulted in Bosnia in 1994. Sent back to her home base, CFB Valcartier in Quebec, she sought the help of a military psychiatrist—who told her the incident was all in her head. When she gave her statement, in English, to the francophone military police, they later translated it into French—leaving out key elements and changing others so that it was unusable in pressing charges. This year, she contacted Baril’s office, and in late June her case was reopened by the NIS. Now, she is confident that the military will finally understand what she suffered. “I’m finally going to get someone to write down on paper that they screwed up,” says Ryan. “I’m feeling positive. I’ve got my fingers crossed. So many women have come forward, something has to happen.”

Such optimism, though, is in short supply among other women who say they were the victims of sexual assault. Tannis Babos-Emond was a 19-year-old military cook when, she says, she was raped by a soldier in 1983 at CFB Borden, 90 km north of Toronto. She did not report the assault at the time, but last spring she contacted Maclean’s with her story—and called the 1-800 line. Initially, she was hopeful about the NIS investigation, but now says “I’ve been brushed off. I wonder why I bothered telling the military my story.” The investigators on her case have been changed twice, she says, and have kept her in the dark about their efforts. “I’ve done more investigating than they have,” says Babos-Emond, who now lives in Cold Lake, Alta. “From August to October, I never heard from them.”

Exasperated by being kept in the dark, she says, she phoned the NIS to get the number for the office of Provost Marshal Patricia Samson—in charge of military police and the NIS. Within half an hour of her call to Samson’s office, an NIS investigator called. He apologized for not getting back to her sooner, explaining that there were only 12 NIS investigators working on almost 200 cases. According to Babos-Emond, he told her that “Your file is right on my desk and it’s going to be a priority.” But she was shocked when he also said how little had been done. “He said the investigators had gone to Borden,” Babos-Emond says in disbelief, “but couldn’t find any files on me. They asked me if I had any pictures of myself in uniform.” On Nov. 12, she was told her case would be handled by another NIS agent. He has yet to call.

Dawn Thomson, who was an ordinary seaman at the time she says she was raped at CFB Esquimalt in 1992, has also spoken to an NIS officer, but was wary during her videotaped interview. “He certainly talked like he was on my side about wanting to help me,’’ she says, “but how much of that can you trust when you have been through what I have been through?” Thomson has taken matters into her own hands. She has launched a civil suit against the military and the two men who allegedly raped her. She and 10 other victims have also started the Canadian chapter of the American-based organization STAMP—Survivors Take Action Against Abuse by Military Personnel (to date, she has had 15 calls from both male and female victims).

Some have refused to talk to investigators. Among them is Dee Brasseur, one of Canada’s first female fighter pilots, who was featured on the cover of the June 1 issue of Maclean’s. Brasseur, who says she was subjected to rape, assault and harassment during a distinguished 21-year military career, believes that the much-vaunted new investigative branch is little more than the now-defunct and notorious Special Investigative Unit of the military police, under a new guise. Established in 1966 to handle security clearances, the SIU was disbanded in mid-1998 after an investigation revealed that most of its high-tech resources—and vast amounts of taxpayer money—were spent hounding gays and lesbians out of the military. “We used to know them as the polyester police, because they always wore polyester suits,” says Brasseur, who now lives in suburban Ottawa, and will receive the Order of Canada at a ceremony at Government House in February. “The new NIS is just the same organization as the old SIU,” Brasseur says. “They have the same purpose, principles, operation and organization. They’re still military. I told them I wasn’t going to be videotaped or audiotaped, that I didn’t want them investigating anything. I don’t trust them.”

Growing numbers of others, though, are taking their chances. Since the Maclean’s reports were published, the Forces have been swamped by complaints about sexual misconduct—both new and old. According to the military’s own numbers, in the first 10 months of this year alone there have been 267 such complaints—almost as many as all other major complaints within the Forces, including theft and assault, combined. That is also nearly double the number filed for all of last year: 145. “With all the publicity and the 1-800 number and the blitz to report, we had an influx,” acknowledges Capt. Alain Bissonnette, spokesman for the provost marshal’s office. “Some of them are historical cases. That boosts our numbers.”

Military officials say the high numbers show that the system is working and that women in the Forces now feel secure enough to bring complaints forward. “Maclean’s brought an issue to light that had to be addressed,” says Samson, 52. “It is my responsibility to go with those complaints—and I did.” Along with the establishment of the 1-800 line, there have been other changes. In June, Defence Minister Art Eggleton announced the appointment of Andre Marin, a former Montreal lawyer, as the military’s first ombudsman, providing an informal clearinghouse for complaints. And last month, Eggleton announced he was re-establishing an advisory board on gender integration, headed by Sandra Perron, the former captain of the Royal 22nd Regiment who left the military in 1996 after being brutally harassed by fellow soldiers.

But suspicion remains. For Toronto’s Rosemary Park, a former lieutenant-commander who researched policy for the military before leaving the Forces in 1993, the advisory board will be just another cosmetic response in a military that needs full reconstructive surgery. “That panel was supposed to be there from 1989 to 1999,” she said. “They did away with it for three years and nobody noticed. It will have no power. It’s just a classic off-to-the-periphery body that will do little.” Still, some female soldiers believe that, since the spring, something has changed—for the better. “These stories pissed a lot of people off,” says Master Cpl. Suzie Fortin, a supply technician at CFB Kingston in Ontario and a 19-year veteran of the Forces. “But they woke a lot of people up.” Fortin, who called the 1-800 number in June with complaints about how her own sexual-assault case was handled in 1996, says that awakening has brought a new awareness. “Now,” she notes, “if someone is going to tell a dirty joke, they ask you if you mind. This has helped a lot of women. Now, they are not scared to come forward. They know people can’t get away with this s–t anymore.”

That represents a sea-change in attitudes, compared with what Fortin encountered in 1993 when she was stationed at CFB Chilliwack in British Columbia. There, a sergeant would routinely come into her office, and in full view of her co-workers draw penises on her calendar. When he assaulted her—by pinning her to her desk, choking her and putting his hand down her shirt—charges were laid (Fortin’s supervising major subsequently got calls from a dozen other women with similar complaints). Although the sergeant was eventually court-martialled, the sexual-assault charges were stayed. He was convicted under Section 129 of the National Defence Act, a military catch-all encompassing conduct prejudicial to “good order and discipline”—the same charge that can be levelled at soldiers for such minor offences as being unshaven or chewing gum.

Fortin, meanwhile, says the worst part of the ordeal was the “three years of hell” she spent leading up to the trial: during that time, she was forced to work alongside her attacker. “The military needs to learn how to treat people who have gone through this,” Fortin said last week, explaining her reasons for calling the 1-800 number. “I wanted them to know this.” Ultimately, it proved to be an exercise in futility. “I never got a call back from them,” says Fortin. “Nothing.”

Since July, the provost marshal’s office has published monthly updates on the department of national defence Web site, tallying the number of sexual assault complaints, investigations launched and charges laid. Officials have also kept a running tab on “the sexual misconduct allegations” that Maclean’s brought to light. According to these reports, the provost marshal has already dispensed with 26 of “the original 31 cases.” They had either been “thoroughly investigated the first time” and required no further action, or “the victims did not want to pursue the matter any further.”

In fact, many of the women who have come forward feel they are nothing more than a number to the military. Despite Baril’s promise that the military was ready to listen, some say their allegations have fallen on deaf ears. When one Ontario woman called the sexual-assault hotline in May and finally talked to an investigator a month later, she bared her soul. The daughter of a serviceman, she says she was raped by a soldier on CFB Kingston in 1978, when she was 16. The woman, who asked that her name be withheld, says that in a separate incident her assailant held a shotgun to her head and threatened to shoot her.

Three years later, she joined the military as a medical assistant but left after three years because, she says, she could not tolerate the harassment she was subjected to. On one occasion, while her husband, a private in the military police, was in the hospital with a collapsed lung, her boss—a captain—tried to order her to go out with him. On another occasion, he pinned her against a wall because she told him she was sick and leaving work early. Later, she was harassed when her sergeant at the Royal Military College told her, “You need to grow tits.” But, more than anything else, the rape continued to haunt her, finally compelling her to call the hotline.

The woman, who is now 37 and studying health at Queen’s University, says the investigation into her allegations was “shockingly incompetent.” When she gave her information to one NIS investigator, she clearly recalled many details, including her assailant’s middle name, the type of car he drove and a description of the tattoo on his left forearm. She was appalled, however, at some of the seemingly absurd questions: for one thing, the officer asked if she remembered her attacker’s social insurance number. And there was also more than a hint of older, chauvinistic attitudes. At the conclusion of another interview, the investigator asked her: “Were you wearing anything provocative that day?”

In September, the NIS investigators found the woman’s alleged assailant, who is now out of the Forces and living in Victoria. When they phoned him and said they were investigating a 1978 sexual assault in Kingston, he allegedly blurted out: “Oh, that must have been —-, she is the only one in Kingston.” After that conversation, he retained a lawyer and has since refused to answer any questions about the charges. Still, the NIS turned the results of their investigation over to the Crown attorney’s office in Kingston.

Last week, though, the Crown decided not to lay charges, saying there was no chance of a successful prosecution. “They said it was just a he-said-she-said case,” said the woman last week. The news left her devastated—and wishing she had never come forward with her complaint. “I am terrified,” she says. “The last time I saw that guy he had a gun in my face. Now that they have contacted him and he knows I am after him, I don’t want to go out of the house. I am so mad because Gen. Baril was on television and saying he was going to right the wrongs and make it better. You go through all this torment and torture and then they pooh-pooh you and send you on your way.”

This case underscores the fact that, while many of the women blame the military for failing to properly prosecute their assailants, the cases often founder in the civilian justice system. Increasingly, Crown attorneys are loath to prosecute historical cases of sexual assault, which often prove costly, time-consuming and, because evidence is hard to collect, difficult to pursue successfully. The provost marshal’s office has acknowledged the problems faced by military women in the civilian justice system. But problems exist in the military’s own backyard. Samson admits that some historical cases may have been “put aside” so that her investigators could concentrate on newer complaints. “You shift your priorities,” said Samson. “I can assure you that cases that occurred in May or June or July of 1998, those got our attention immediately.”

Krista Piche, who now lives in Winnipeg, was hopeful the NIS could successfully prosecute the petty officer she says raped her while she was a communications researcher at Canadian Forces Station Alert, the northernmost military installation in Canada. After all, the incident happened only four years ago, and the officer is still in the military at CFS Leitrim in Ottawa. Besides, she says, the military knew that another servicewoman—on the same six-month tour of duty—had filed a similar complaint against the petty officer, and that a fellow serviceman had corroborated that woman’s story.

That woman later dropped the charges, and Piche’s complaint ground to a halt largely because of problems deciding where to try the case. Still, she believes there was enough evidence for the military to re-examine her allegations. But when she spoke to the NIS, she was told there would be no further action taken against the petty officer, who three years ago was dealt with administratively and given six months counselling and probation. “They tried to appease me by phoning me and saying they were looking into it,” says Piche, “but other than that, I’m just one of their statistics. I’m out of the military now and they don’t have to worry about me. I just don’t know how to stick up to them and make it go anywhere after this.”

Others, meanwhile, are turning to the military with complaints of outright brutality—with disappointing results. Joan Harper, who in 1989 was one of the first women to go through infantry training in the Forces, spoke to the NIS in May about her treatment at the Wainwright Training School in Alberta—and was told the three-year statute of limitations had run out on pursuing charges for such military offences as abuse of power. Although she was not sexually assaulted, Harper was kicked and beaten, to the point of being hospitalized, by four other women in her unit. She believes her sergeant instructor at the time was responsible. When he came to see her in the hospital after the assault, he assured her it would be safe to return to the unit and nothing more would happen to her. “I asked him how he could be so sure I was safe, and he told me, ‘I can turn them on and I can turn them off,’” recalls Harper, who now lives in Toronto and still suffers permanent back pain because of the attack. “But when I returned to my unit there was a noose on my bed.”

Harper’s mother, Jean Sutherland, was outraged at the time of the assault—and was immediately flown from Toronto to Wainwright after she informed William McKnight, then Tory minister of defence, that she would go to the media if he did not arrange for her to see her daughter immediately. “A couple of weeks earlier, the CBC had done a big story on Joan and the other women and how wonderful it was for them to be in that first battle school,” says Sutherland. “I asked the minister how he’d like to see Joan on TV again, with her face all black and blue, after her sergeant had ordered her to be beaten up.” After a cursory investigation into the incident, one of the four women who beat Harper up was fined $50. Harper left the Forces six weeks after the assault.

According to many who have been in the Forces, the abuse endured by Harper is a routine technique for forcing soldiers who don’t quite measure up to shape up or ship out. (In some cases, it is known in the trade as a “blanket party” because a blanket is usually thrown over the head of the victim before they are attacked—ensuring that the attackers cannot be identified.) Even before the assault on her, Harper had already had a taste of that brutality. In 1988, while training with her reserve unit, the Queen’s Own Rifles, at a camp outside CFB Borden, Harper woke up one morning to find a fellow reservist had been beaten senseless during the night. When the victim told her what had happened, Harper was put in protective custody while the case was being investigated. In the end, the master corporal who had encouraged the attack was presented with the choice of resigning or being given a dishonorable discharge. He resigned quietly and no further action was taken.

Tanya Botting, a reservist in Victoria from 1991 to 1994, recalls a fellow soldier who was attacked by a gang who whipped him with bars of soap stuck in the ends of socks. His crime? His attackers believed he was gay. “It’s just part of the code, the army’s way of handling people who are homosexuals,” says Botting, 28. “There’s so much discrimination against them, they don’t dare let on what they’re about.” Other soldiers concur with her assessment. “Gays are still perceived as an abomination,” says one former soldier who left the Forces in 1996 and admits he took part in this primitive form of punishment. “There’s an unbelievable hatred for them—you can’t even measure it. But gays weren’t the only ones who got blanket parties. Almost always they were ordered by the instructors. They’d come into a platoon and say, ‘There’s a f— -up who’s bringing this platoon down. You’ve got to sort your people out.’ And we’d sort them out.”

To this day, Sutherland is angry that no charges were ever brought against the sergeant who ordered the attack on her daughter. But she thinks she is wasting her time trying to get justice from the Canadian Forces or the government. “Ten years have passed and she is still carrying the pain of this,” says Sutherland. “But I have no trust that the government will do anything or even acknowledge her grievance. If they do anything, they’ll strike a committee to study the problem and then strike an ad hoc committee to study that committee. You can’t fight them.”

But there is hope. One woman who was assaulted a year ago while serving in Bosnia told Maclean’s last week that charges were brought against her assailant, who was sentenced to eight months in military prison last week. According to the woman, who asked to remain anonymous, the military “is doing its part in trying to eradicate this problem, and the NIS is considerably effective with the reports that it does receive.” But, she said, factors such as alcoholism and promiscuity still loom large within the Forces, and change will not come until members of the military “start respecting others and see their own behaviour for what it is.” According to her, there is also another course of action. “I fear there are many other victims out there who have not spoken out yet,” she said. “My one big wish is for these people to have the courage to do so—that is the only way to put an end to all this violence.” It is a call to arms that some military women are heeding.