Read the judge’s ruling in the Jian Ghomeshi case

The Jian Ghomeshi ruling runs about 11,000 words and took more than an hour to read aloud. We publish it here, for the record.

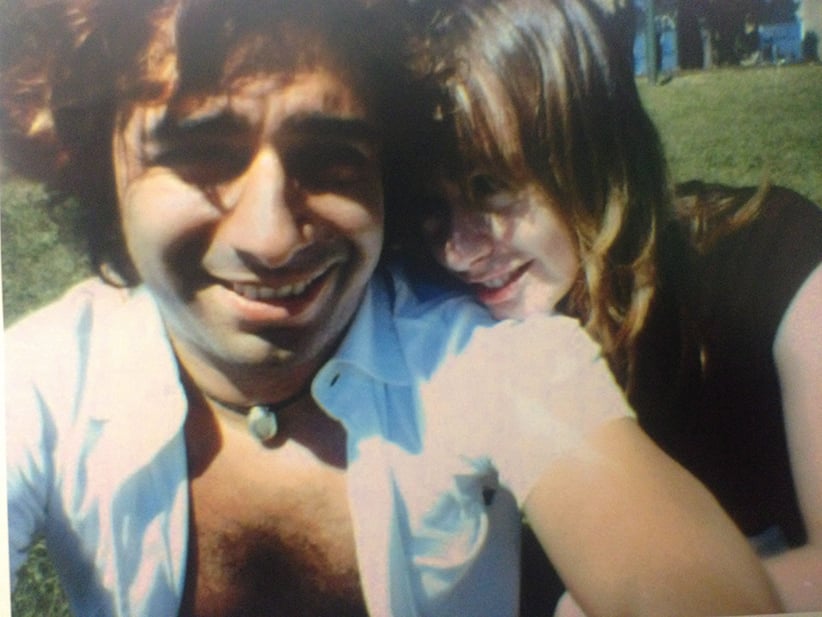

Former CBC radio host Jian Ghomeshi arrives at a Toronto court for day five of his trial on Monday, Feb. 8, 2016. (Chris Young/CP)

Share

WARNING: The court hearing this matter directs that the following notice be attached to the file:

A non-publication and non-broadcast order in this proceeding has been issued under subsection 486.4(1) of the Criminal Code. This subsection and subsection 486.6(1) of the Criminal Code, which is concerned with the consequence of failure to comply with an order made under subsection 486.4(1), read as follows:

486.4 Order restricting publication — sexual offences.—(1) Subject to subsection (2), the presiding judge or justice may make an order directing that any information that could identify the complainant or a witness shall not be published in any document or broadcast or transmitted in any way, in proceedings in respect of

(a) any of the following offences:

(i) an offence under section 151, 152, 153, 153.1, 155, 159, 160, 162, 163.1, 170, 171, 172, 172.1, 173, 210, 211, 212, 213, 271, 272, 273, 279.01, 279.02, 279.03, 346 or 347,

(ii) an offence under section 144 (rape), 145 (attempt to commit rape), 149 (indecent assault on female), 156 (indecent assault on male) or 245 (common assault) or subsection 246(1) (assault with intent) of the Criminal Code, chapter C-34 of the Revised Statutes of Canada, 1970, as it read immediately before January 4, 1983, or

(iii) an offence under subsection 146(1) (sexual intercourse with a female under 14) or (2) (sexual intercourse with a female between 14 and 16) or section 151 (seduction of a female between 16 and 18), 153 (sexual intercourse with step- daughter), 155 (buggery or bestiality), 157 (gross indecency), 166 (parent or guardian procuring defilement) or 167 (householder permitting defilement) of the Criminal Code, chapter C-34 of the Revised Statutes of Canada, 1970, as it read immediately before January 1, 1988; or

(b) two or more offences being dealt with in the same proceeding, at least one of which is an offence referred to in any of subparagraphs (a)(i) to (iii).

(2) Mandatory order on application.— In proceedings in respect of the of- fences referred to in paragraph (1)(a) or (b), the presiding judge or justice shall (a) at the first reasonable opportunity, inform any witness under the age of eighteen years and the complainant of the right to make an application for the order; and (b) on application made by the complainant, the prosecutor or any such witness, make the order.

…

486.6 Offence.—(1) Every person who fails to comply with an order made under subsection 486.4(1), (2) or (3) or 486.5(1) or (2) is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.

ONTARIO COURT OF JUSTICE

CITATION: [Reserved] DATE: 2016·03·24 COURT FILE No.: Toronto 4817 998 15-75006437

BETWEEN:

HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN — AND —

JIAN GHOMESHI

Before Justice William B. Horkins

Heard on February 1 through February 11, 2016 Reasons for Judgment released on March 24, 2016

Michael Callaghan and Corie Langdon …………………………………….. counsel for the Crown Marie Henein, Danielle Robataille and Samuel Walker………………. counsel for the accused

HORKINS, W. B., J.: INTRODUCTION

[1] Jian Ghomeshi is charged with five criminal offences relating to four separate events, involving three different complainants. Two of the complainants are shielded from identification and so I refer to the complainant in counts 1 and 2 by the initials L.R. and the complainant in count 5 by the initials S.D.

[2] The charges with respect to L.R. are two counts of sexual assault. The first assault is alleged to have occurred between December 1st and 31st, 2002 and the second assault on January 2nd, 2003.

[3] The charges with respect to Lucy DeCoutere are sexual assault and overcoming resistance to sexual assault by choking. These events were originally alleged to have occurred between the 27th of June and the 2nd of July 2003 but this has since been amended to conform to the evidence that the events occurred between the 4th and 6th of July 2003.

[4] The charge with respect to S.D. is sexual assault. This was originally alleged to have occurred between the 15th and 20th of July 2003. This has now been amended to conform to the evidence that the event occurred between the 15th of July and the 2nd of August 2003.

The Elements of the Offences

[5] A criminal “assault” is an intentional application of force to the person of another without that person’s consent. A “sexual assault” is an assault committed in sexual circumstances such that the sexual integrity of the victim is violated. The test to determine if an assault is “sexual” is an objective one. This test asks whether the sexual nature of the contact would be apparent to a reasonable person when viewed in light of all of the circumstances. The actual intent of the accused is only one factor amongst many that may determine if the conduct involved is “sexual.”

[6] “Sexual assault” as defined in our Criminal Code covers a very broad spectrum of offensive activity; everything from an uninvited sexual touching to a brutal rape falls under the one title of “sexual assault.” The events as described by each of the complainants, taken at face value, fall within this broad definition. Each allegation of violence occurred in an intimate situation.

[7] With respect to the complainant Lucy DeCoutere, there is an added charge of choking with intent to overcome resistance. This offence is committed when a perpetrator attempts to choke the victim with the intent of facilitating the commission of an offence; in this instance, a sexual assault.

Background Context of the Case

[8] At the time of the events in question, 2002 to 2003, Mr. Ghomeshi was the host of a CBC television show called “PLAY”. Subsequently, and for several years prior to when these complainants came forward in 2014, he was the host of a CBC radio show called Q. Q is a show which features interviews with prominent cultural and entertainment figures. With Mr. Ghomeshi as the host, Q enjoyed a large and dedicated following.

[9] It is fair to say that in 2014 Mr. Ghomeshi had achieved celebrity status and was a prominent and well-known personality in the arts and entertainment community in Canada. Then, suddenly, in 2014 the CBC publicly terminated him in the midst of several allegations of disreputable behaviour towards a number of women.

[10] The publicity surrounding what I will call the “Ghomeshi Scandal” in 2014 is the context in which the complainants in this case came forward with reports of sexual assaults that they say occurred in 2002 and 2003.

[11] Each charge presented against Mr. Ghomeshi is based entirely on the evidence of the complainant. Given the nature of the allegations this is not unusual or surprising; however it is significant because, as a result, the judgment of this Court depends entirely on an assessment of the credibility and the reliability of each complainant as a witness.

THE COMPLAINT OF L.R.

[12] The first two counts of the Information are allegations that the accused sexually assaulted the complainant L.R. on two different occasions. The first occasion is identified as having occurred on a date between December 1st and 31st, 2002. The second allegation is identified as having occurred on the 2nd of January 2003.

[13] L.R. first met Mr. Ghomeshi while working as a server at the 2002 CBC Christmas party. She felt that they made a connection. They flirted with each other and she found Mr. Ghomeshi to be charming and charismatic. When speaking of this first meeting, she reported: “He was smitten with me.” He seemed very enthusiastic. Mr. Ghomeshi invited L.R. to attend a future taping of his show “PLAY” and gave her a note with the time and the place of the taping.

[14] L.R.’s evidence was that on the evening she went to the show Mr. Ghomeshi’s eyes lit up when he saw her arrive and he exclaimed, excitedly, “You came!”

[15] The show was taped in a restaurant bar. L.R. sat at the bar where she was close to Mr. Ghomeshi during the show. After the show he asked her to accompany him and some other CBC personalities to a nearby pub for a drink. L.R. remembers that Mr. Ghomeshi was sweet and humble. She recalled certain small details of the evening, for instance, he ordered a Heineken and she had a ginger ale. She thought he was funny, intelligent, charming and a nice person.

[16] After about half an hour Mr. Ghomeshi and L.R. left the pub. He drove her to her car that was parked a short distance away. L.R. had a clear and very specific recollection of his car being a bright yellow Volkswagen Beetle. It struck her as being a “Disney car”, a “Love Bug”. She said she was impressed that he was not driving a Hummer or some such vehicle. The “Love Bug” car was significant to her because it contributed to her impression of his softness, his kindness and generally, that it was safe to be with him.

[17] When they arrived at the parking lot where L.R.’s car was parked they sat in his car and talked. Mr. Ghomeshi was flirtatious and it was playful. He asked her to undo some of the buttons of her blouse and she said no. She was

flirting with him. They were kissing, when suddenly he grabbed hold of her long hair and yanked it “really, really hard”. She said her thoughts at the time were: “What have I gotten into here?”

[18] L.R. described the yank to her hair as painful. Mr. Ghomeshi asked her if she liked it like that, or words to that effect. They sat and talked for a while longer. Mr. Ghomeshi had reverted back to being very nice. It was confusing and L.R. was unsure what to think. She wondered if maybe he did not know his own strength. They kissed goodbye. L.R. got out of the car and drove home. She continued to ask herself whether he had really intended to hurt her.

[19] L.R. was obviously very much taken with Mr. Ghomeshi. She was separated from her husband at the time and agreed that she was considering Mr. Ghomeshi as someone she would potentially be interested in going out with. She decided to attend another taping of Mr. Ghomeshi’s show. He met her there and was very nice to her. It was, to use her expression, “uneventful”.

[20] During the first week of January 2003, L.R. attended another taping of Mr. Ghomeshi’s show. On this occasion she went with a girlfriend. L.R. recounts that Mr. Ghomeshi was happy to see them. They interacted and after the show they all went to the pub. They were at the pub for less than an hour. L.R. said that she flirted with Mr. Ghomeshi. He invited both women back to his home. L.R.’s friend declined. After they dropped off her friend at the subway, L.R. and Mr. Ghomeshi drove to his home.

[21] While at Mr. Ghomeshi’s home the music was playing. They had a drink, and they sat on the couch and talked. At one point L.R. was standing up near the couch, looking at various things in the room and thinking what a charming person he was. Then, suddenly, “out of the blue”, he came up behind her, grabbed her hair and pulled it. He then punched her in the head several times and pulled her to her knees. The force of the blow was significant. She said it felt like walking into a pole or hitting her head on the pavement. L.R. thought she might pass out.

[22] Then, suddenly again, the rage was gone and Mr. Ghomeshi said, “You should go now; I’ll call you a cab.” L.R. waited for the cab then left. She said, “He threw me out like the trash.”

[23] L.R.’s evidence was that at the time of these events in 2003, she never thought of calling the police. She did not think anyone would listen to her. L.R. said she never saw Mr. Ghomeshi again after this incident.

[24] Over a decade later, Mr. Ghomeshi was fired from the CBC and the “Ghomeshi Scandal” broke in the media. L.R. came forward publically with her complaint in response to the publicity and specifically, in response to then Chief Blair of the Toronto Police Service publically encouraging those with complaints about Jian Ghomeshi to come forward.

[25] Several areas of concern in L.R.’s evidence were identified in cross- examination.

An Evolving Set of Facts

[26] Prior to speaking with police, L.R. gave three media interviews about her allegations against Mr. Ghomeshi. In these interviews, she described the first assault as happening “out of the blue”, as opposed to having happened in the midst of a kissing session. Her police statement was initially similar to her media interviews. It was only near the end of her police statement that L.R. had the hair pulling and kissing “intertwined”. Then at trial, the account of the event had developed to the point of the hair pulling clearly occurring at the same time as “sensuous” kissing. The event had evolved from a “common” assault into a sexual assault.

[27] When pressed about the shifting facts in her version of the events, L.R. explained that while she was giving the media interviews, she was unsure of the sequencing of events and “therefore … didn’t put it in”.

The Hair Extensions

[28] The day following her police interview, L.R. sent a follow up email to the police to explain that she remembered very clearly that she was wearing clip-on hair extensions during the hair pulling incident in the car. In cross-examination, L.R. testified that at some point she reversed this “clear” memory and is now adamant that she was not wearing clip-on hair extensions during the incident.

[29] L.R. frequently communicated with police by email and phone. She met and spoke with Crown counsel. She did nothing to correct the misinformation she provided to the police about the hair extensions. Equally as concerning as the reversals on this point, was her claim that she had, in fact, disclosed this reversed memory to the Crown. When pressed in cross-examination, she conceded that this was not true.

The Car Window Head Smash

[30] The day after her police interview, L.R. emailed the police to explain that she was then beginning to remember that during the car incident, Mr. Ghomeshi smashed her head into the window. In her previous four accounts of the incident, provided to police and the media, she had never claimed that her head had been smashed into the car window. Under cross-examination, she reverted to the version of the car incident with no head smash. She then added that her head had been resting against the window; something she had never mentioned previously, at any time.

[31] When pressed to explain these variations, L.R. said that at her police interview she was simply “throwing thoughts” at the investigators.

[32] When cross-examined about her new allegation of having her head smashed into the window, L.R. denied demonstrating in her sworn police video statement that her hair was pulled back towards the seat of the car, not towards or into the window. She persisted in her denial of this, even when the police video was played, clearly showing her demonstrating to the detectives how her hair was pulled back. Her explanation for this shifting in her evidence was that during the police interview she was “high on nerves”.

[33] L.R.’s memory about the assault at the house also shifted and changed significantly. She told the Toronto Star and CBC TV that she was pulled down to the floor prior to being assaulted at the house. She told CBC Radio that she was thrown down to the ground. Then she told the police that the events were “blurry” and did not know how she got to the ground. When trying to reconcile all of these inconsistencies she said that, to her, being “thrown” and being “pulled” to the ground are the same thing.

[34] In her police interview, L.R. did not initially describe kissing as part of the alleged assault and was unable to describe a clear sequence of events. At trial, for the first time, she had kissing clearly intertwined with the alleged assault. She remembered kissing on the couch and kissing standing up. L.R. could not describe the conversation or what they were each doing prior to the assault. In her evidence in-chief, there was no mention of doing a yoga pose just prior to the assault. In cross-examination, L.R. was reminded of the yoga moves and her earlier statement that Mr. Ghomeshi was bothered by them.

The “Love Bug”

[35] One of L.R.’s clear memories was simply, and demonstrably, wrong. She testified at length about Mr. Ghomeshi’s bright yellow Volkswagen “Love Bug” or “Disney car”. This was a significant factor in her impression that Mr. Ghomeshi was a “charming” and nice person. However, I find as a fact that Mr. Ghomeshi did not acquire the Volkswagen Beetle that she described until seven months after the event she was remembering.

[36] In a case which turns entirely on the reliability of the evidence of the complainant, this otherwise, perhaps, innocuous error takes on greater significance. This was a central feature of her assessment of Mr. Ghomeshi as a “nice guy” and a safe date. Her description of his car was an important feature of her recollection of the first date. And yet we know that this memory is simply wrong. The impossibility of this memory makes one seriously question, what else might be honestly remembered by her and yet actually be equally wrong? This demonstrably false memory weighs in the balance against the general reliability of L.R.’s evidence as a whole.

The Flirtatious Emails

[37] L.R. was firm in her evidence that following the second incident she chose never to have any further contact with Mr. Ghomeshi. She testified that every time she heard Mr. Ghomeshi on TV or radio, she had to turn it off. The sound of Mr. Ghomeshi’s voice and the sight of his face made her relive the trauma of the assault. L.R. could not even listen to the new host of Q because of the traumatizing association with Mr. Ghomeshi.

[38] L.R.’s evidence in this regard is irreconcilable with subsequently proven facts. She sent a flirtatious email to Mr. Ghomeshi a year later. In her email, L.R calls Mr. Ghomeshi “Play-boy”; a reference to his show. She refers, oddly, to him ploughing snow, naked. She says it was “good to see you again.” She is either watching him, or watching his show. “Your show is still great,” she writes. She invites him to review a video she made and provides a hotlink embedded into the body of the message. L.R. provides him with her email address and phone number so he can reply. Despite her invitation, she received no response. This is not an email that L.R. could have simply forgotten about and it reveals conduct that is completely inconsistent with her assertion that the mere thought of Jian Ghomeshi traumatized her.

[39] Six months later, L.R. sent another email to Mr. Ghomeshi. In it she said, “Hi Jian, I’ve been watching you …” (here expressly referencing another TV show), “hope all is well.” She attached to this email a picture entitled “beach1.jpg”, which is a picture of her, reclined on a sandy beach, wearing a red string bikini. This is not an email that she could have simply forgotten about. It reveals conduct completely inconsistent with her assertion that the mere thought of Mr. Ghomeshi traumatized her.

[40] The negative impact that this after-the-fact conduct has on L.R.’s credibility is surpassed by the fact that she never disclosed any of this to the police or to the Crown.

[41] It was only after she was confronted in cross-examination with the actual emails and attachment that L.R. suddenly remembered not just attempting to contact Mr. Ghomeshi but also that it was part of a plan. She said that her emails were sent as “bait” to try to draw out Mr. Ghomeshi to contact her directly so that she could confront him with what he had done to her.

[42] I suppose this explanation could be true, except that this spontaneous explanation of a plan to bait Mr. Ghomeshi is completely inconsistent with her earlier stance that she wanted nothing to do with him, and that she was traumatized by the mere thought of him. I am unable to satisfactorily reconcile her evidence on these points.

[43] The expectation of how a victim of abuse will, or should, be expected to behave must not be assessed on the basis of stereotypical models. Having said that, I have no hesitation in saying that the behaviour of this complainant is, at the very least, odd. The factual inconsistencies in her evidence cause me to approach her evidence with great skepticism

[44] L.R.’s evidence in-chief seemed rational and balanced. Under cross- examination, the value of her evidence suffered irreparable damage. Defence counsel’s questioning revealed inconsistencies, and incongruous and deceptive conduct. L.R. has been exposed as a witness willing to withhold relevant information from the police, from the Crown and from the Court. It is clear that she deliberately breached her oath to tell the truth. Her value as a reliable witness is diminished accordingly.

THE COMPLAINT OF LUCY DECOUTERE

[45] I turn now to the charges relating to Ms. DeCoutere. She said that she was choked and sexually assaulted in 2003. She came forward publically with her allegations at the time of the intense publicity surrounding the CBC’s dismissal of Mr. Ghomeshi in 2014.

[46] Ms. DeCoutere first met Mr. Ghomeshi at the Banff Film Festival in June of 2003. They enjoyed each other’s company. Ms. DeCoutere found Mr. Ghomeshi playful and flirtatious, and came away thinking he would be fun to be with. They stayed in touch and planned to get together in Toronto over the upcoming Canada Day long-weekend. She travelled from her home in Halifax to visit with Mr. Ghomeshi as well as other friends living in Toronto.

[47] Early in her weekend visit, Ms. DeCoutere and Mr. Ghomeshi went out for dinner. They enjoyed some pleasant conversation. He told her he would like to go back to his place and listen to some music and just hold her. She thought that this was “cheesy” and “put on”. After dinner they did go back to his home, a short walk from the restaurant. Along the way he made a move to kiss her. She thought the attempt seemed awkward.

[48] Mr. Ghomeshi gave Ms. DeCoutere a tour of his house. She was impressed with how organized and well-kept it was. Then, suddenly, out of the blue, he kissed her. Ms. DeCoutere described how Mr. Ghomeshi put his hand onto her throat and pushed her forcefully to the wall, choking her and slapping her in the face. She was shocked, surprised and bewildered. She tried to remain calm and act as if nothing unusual had happened. She stayed a while longer. They listened to music and he played his guitar. Then, with a kiss good night, she left.

[49] Over the course of the weekend Ms. DeCoutere and Mr. Ghomeshi attended several social events together. She thought that the assault might have been a mistake or a “one off” of some sort. She internalized it. On one occasion, she returned briefly to his home. She recalls accidentally stepping on his glasses and that this upset him. She reports that he had become moody but there were no further acts of violence. Ms. DeCoutere firmly stated that after this weekend she had no intention of having any sort of ongoing personal relationship with Mr. Ghomeshi.

[50] After the weekend, Ms. DeCoutere sent Mr. Ghomeshi flowers in appreciation of him being such a great host during her visit to Toronto.

[51] In October of 2003 their paths crossed at the Gemini Awards dinner in Toronto. The television series in which she was a cast member was nominated. Mr. Ghomeshi came to her table, chatted and at one point reached out and touched her neck. Ms. DeCoutere interpreted this touch to the neck as an unsettling reminder of the July assault.

[52] In June 2004 both Ms. DeCoutere and Mr. Ghomeshi attended the Banff Film Festival and they spent time together there. At a karaoke event at the Banff Springs Hotel, Ms. DeCoutere was on the stage singing the Britney Spears song “Hit Me Baby One More Time”. Mr. Ghomeshi joined her in a duet. She characterized the performance as “hilarious”.

[53] After the 2004 Banff Film Festival they met occasionally at industry events. When being interviewed about their history together prior to 2014, Ms. DeCoutere acknowledged that there were probably more social meetings and dinners, the details of which she could not recall. She referred to these meetings as “inconsequential”.

[54] Ms. DeCoutere did not report this assault in 2003 because she thought that the incident was not serious enough. She said that she thought you had to be “beaten to pieces … broken and raped” before going to the police. Ms. DeCoutere came forward publically with her complaint in 2014, when she heard of Mr. Ghomeshi being terminated by the CBC. Ms. DeCoutere said that her plan was to take her experience to the press. She came to Toronto and gave numerous media interviews. She said that she was not interested in legal action being taken against Mr. Ghomeshi. She only went to the police because they had asked for anyone with information to speak to them.

[55] Ms. DeCoutere’s credibility and reliability as a witness were vigorously challenged in cross-examination, revealing serious problems with accepting her evidence at full value.

Late Disclosure of Material Information

[56] Just prior to Ms. DeCoutere being called as a witness, she met with the Crown and police and revealed a significant amount of new information to the prosecution. This last-minute disclosure of information occurred despite having the assistance of her own counsel throughout the many months leading up to the trial and despite her acknowledgment that a line of communication with the investigating officers and Crown counsel was well-established throughout this period of time.

[57] Ms. DeCoutere insisted that her late disclosure was spontaneous and denied being aware that the previous witness, L.R., had been confronted with embarrassing emails from 2004. Ms. DeCoutere insisted that her reason for coming forward with new information on February 2, 2016, was that she did not understand the “importance” or “impact” of the information until then.

[58] In cross-examination Ms. DeCoutere confirmed that she did not mention in her sworn police interview, or in any of her 19 reported media interviews, that Mr. Ghomeshi had attempted to kiss her during their walk to his home; that they kissed on the couch after the alleged assault; that they kissed goodnight when she left his home that evening. None of that was disclosed prior to the trial.

[59] When asked directly by Detective Ansari in her police interview what she and Mr. Ghomeshi did in the time between the alleged assault and her departure from his home, she simply said “nothing stuck” in her memory. Trying to explain this inconsistency, she testified that she did not think kissing with her assailant after the alleged assault was very “consequential”.

[60] It is difficult for me to believe that someone who was choked as part of a sexual assault, would consider kissing sessions with the assailant both before and after the assault not worth mentioning when reporting the matter to the police. I can understand being reluctant to mention it, but I do not understand her thinking that it was not relevant.

[61] Ms. DeCoutere remembered and reported minute details of their date: what Mr. Ghomeshi ordered at the restaurant; how he organized his shirts; that the temperature of his house was perfect; and that fresh flowers were on the table. All this was memorable and remarkable, yet she claimed to have left out the kissing and the cuddling because she thought brevity and succinctness were important. I do not accept this as a credible explanation.

[62] Ms. DeCoutere repeatedly stated that Mr. Ghomeshi’s suggestion about lying down together and listening to music was creepy, cheesy or otherwise unappealing. It made her instantly uncomfortable. However, five days later, when she penned him a “love letter”, she wrote, “What on earth could be better than lying with you, listening to music and having peace?”

Inconsistencies in Recounting the Alleged Assault

[63] Ms. DeCoutere told the police, under oath, that her recollection of the events that took place at Mr. Ghomeshi’s house was “all jumbled”. She told them that at a certain point she and Mr. Ghomeshi started kissing but, “I don’t remember the order of events.” She was not sure whether the choking or the slapping came first. However, when she spoke to the Toronto Star a few days prior to her police interview, she said that it was choking and then slapping. When she spoke to the CTV, she was not sure about the order. At trial, for the first time, she gave a clear and specific sequence of events: a push up against the wall; two slaps; a pause, and then another slap. She acknowledged in cross-examination that this was, again, another new or different version of the events.

[64] An inability to recall the sequence of such a traumatic event from over a decade ago is not very surprising and in most instances, it would be of little concern. However, what is troubling about this evidence is not the lack of clarity but, rather, the shifting of facts from one telling of the incident to the next. Each differing version of the events was put forward by this witness as a sincere and accurate recollection.

[65] When a witness is comfortable with giving differing versions of the same event, it suggests a degree of carelessness with the truth that diminishes the general reliability of the witness.

Disclosure of an Ongoing Relationship

[66] Lucy DeCoutere swore to the police that after the alleged assault in 2003 she only saw Mr. Ghomeshi “in passing”. She was polite to him, only because she did not want to jeopardize her future professional prospects. She “didn’t pursue any kind of relationship” with him. Ms. DeCoutere was asked directly by the police interviewers to tell them everything about her relationship with Mr. Ghomeshi, before and after the alleged assault.

[67] It became clear at trial that Ms. DeCoutere very deliberately chose not to be completely honest with the police. Her statement to the police was what initiated these proceedings. This statement was subject to a formal caution concerning the potential criminal consequences of making a false statement. It was given under oath, an oath to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, not a selective version of the truth. Despite this formal caution and oath, Ms. DeCoutere proceeded to consciously suppress relevant and material information. This reflects very negatively on her general reliability and credibility as a witness. It indicates a failure to take the oath seriously and a wilful carelessness with the truth.

[68] On the evening of the second day of trial and just before Ms. DeCoutere was set to testify, her lawyer approached Crown counsel with a question. If there was more to the post-assault relationship between Ms. DeCoutere and Mr. Ghomeshi than what had already been disclosed, would the Crown be interested in knowing about it? I can only imagine Crown counsel’s reaction.

[69] A further formal, sworn police statement was taken from Ms. DeCoutere and then disclosed to the defence. This new statement disclosed for the first time the fact that Ms. DeCoutere sent flowers to Mr. Ghomeshi days after the alleged choking. It disclosed for the first time that she and Mr. Ghomeshi spent a considerable amount of time together in Banff in 2004. She also acknowledged that there were additional emails between them. All of this was deliberately withheld by Ms. DeCoutere up until this point in time.

[70] I do not accept that Ms. DeCoutere could have sincerely thought that all this was inconsequential and of no interest to the prosecution. She may have been afraid to disclose this information. She may have been embarrassed to disclose this information. These would not be unreasonable feelings; but to say that she decided not to disclose this information because she thought it was of no importance is just not credible.

[71] To make matters worse, when given this last-minute opportunity to make full disclosure, she still failed to do so.

Additional Deception Revealed in Cross-examination

[72] In an effort to explain to the Court her continued socializing with Mr. Ghomeshi following the alleged choking incident and over the rest of the 2003 Canada Day weekend, Ms. DeCoutere testified that she wanted to “normalize” the situation and “flatten the negative”, and to not make him feel like a bad host. So, she stuck with their plans and she continued to see him over the weekend. She testified that she kept her distance and certainly did not do anything intimate with him. Having firmly committed herself to this position, she was then confronted with a photograph of herself cuddling affectionately in the park with Mr. Ghomeshi the very next day.

Banff 2004

[73] Ms. DeCoutere’s new disclosure included, for the first time, information about her contact with Mr. Ghomeshi at the 2004 Banff festival, including the “Hit Me Baby One More Time” karaoke duet. She attempted to explain the last-minute timing of this disclosure as being the “first chance” that she felt she had to tell anyone. I find this explanation unconvincing coming from a witness who had been interviewed dozens of times prior to trial, had established a continual flow of email correspondence with the investigating police, and who had her own lawyer involved in the case for a year and a half leading up to the trial. If she truly intended to provide this information, she had ample means and opportunity to do so.

[74] After the 2004 Banff festival, Ms. DeCoutere sent Mr. Ghomeshi a photograph of their Banff Springs “Hit Me Baby One More Time” karaoke performance with the caption “proof that you can’t live without me.” When confronted in cross-examination with this photograph and the “playful” caption, her explanation was that this was part of an effort to make Mr. Ghomeshi “less of an assaulter and more of a friend.” This explanation lacks credibility when combined with the further details brought out in cross-examination about the Banff 2004 visit.

[75] In advance of going to Banff, Ms. DeCoutere emailed Mr. Ghomeshi and told him that she wanted to “play” with him when they were in Banff. She suggested that maybe they would have a “chance encounter in the broom closet.” The response from Mr. Ghomeshi was expressly non-committal, “I’d love to hang but can’t promise much.”

[76] Ms. DeCoutere emailed back to Mr. Ghomeshi saying she was going to “beat the crap” out of him if they didn’t hang out together in Banff and that she would like to “tap [him] on the shoulder for breakfast.” This correspondence paints a suggestive picture. It reads as if Ms. DeCoutere was, at that point in time, clearly pursuing Mr. Ghomeshi with an interest in spending more time together.

[77] A natural assumption might be that what was actually stopping Ms. DeCoutere from sharing all of this undisclosed information, was the fear that to some audiences this post-event socializing would reflect badly on her claims that this man had in fact assaulted her.

[78] Had she genuinely feared that this sort of thinking would unfairly undermine her credibility, that concern might have been an explanation worth giving careful consideration. However she offered an entirely different explanation for supressing this information.

[79] Ms. DeCoutere said her plan was to disclose all of these things once the trial began. She said that she had always intended to reveal this information but thought that the trial would be her first chance to do so. With respect, that explanation seems unreasonable to me. Ms. DeCoutere had literally dozens of pre-trial opportunities to provide the full picture to the authorities. I suspect the truth is she simply thought that she might get away with not mentioning it.

The Flowers

[80] Another item in the new disclosure statement was the information that Ms. DeCoutere sent flowers to Mr. Ghomeshi following the Canada Day weekend in Toronto. Within days of when she says she was choked by Mr. Ghomeshi, she sent him flowers to thank him for being such a good host. Sending thank-you flowers to the man who had just choked you, may seem like odd behaviour. I acknowledge that this might be part of her effort, as she said, to normalize the situation. However, whether or not this behaviour should be considered unusual or not, this was very clearly relevant and material information in the context of a sexual assault allegation. The deliberate withholding of the information reflects very poorly on Ms. DeCoutere’s trustworthiness as a witness.

The Undisclosed Evidence of a Continued Relationship

[81] I find as a fact that Ms. DeCoutere attempted to mislead the Court about her continued relationship with Mr. Ghomeshi. It was only during cross- examination that her expressed interest in a continuing close relationship was revealed.

[82] Ms. DeCoutere testified that after the weekend in Toronto in July 2003, she definitely knew that she did not want to have a romantic relationship with Mr. Ghomeshi. She gave us her “guarantee” under oath that she had no romantic feelings for Mr. Ghomeshi. Even in her late disclosure, just prior to taking the stand, Ms. DeCoutere claimed that any personal contact with Mr. Ghomeshi following the Canada Day long-weekend in 2003 was simply an attempt to “flatten out [her] negative.” She maintained that any emails that she sent to Mr. Ghomeshi following that weekend were “indifferent” in tone and not “playful”, as they had been previously.

[83] Once again this was simply not true. In an email sent just two weeks later, on July 17, 2003, Ms. DeCoutere told Mr. Ghomeshi that he was “magic”. On July 25, 2003, three weeks after the alleged assault, she wrote to Mr. Ghomeshi that she was “really glad to know you”. On April 6, 2004, she wrote an email to Mr. Ghomeshi suggesting help with “an itch that you need… scratching”. On October 19, 2005, she sent him what she described herself as a “ridiculous, sexualized photo” of herself with the neck of a beer bottle in her mouth simulating an act of fellatio. As recently as September 8, 2010, she posted a Facebook message fondly recalling the 2003 Canada Day weekend.

[84] On July 5th 2003, within 24 hours of the alleged choking incident, Ms. DeCoutere emailed Mr. Ghomeshi with the message:

“Getting to know you is literally changing my mind, in a good way. You challenge me and point to stuff that has not been pulled out in a very long time. I can tell you about that some- time and everything about our friendship so far will make sense. You kicked my ass last night and that makes me want to fuck your brains out, tonight.”

There is not a trace of animosity, regret or offence taken, in that message.

[85] Five days after the alleged choking assault, Ms. DeCoutere was home in Halifax and she sent a hand-written love letter to Jian Ghomeshi. She expressed her regret that she and Mr. Ghomeshi had not spent that night together. The letter concludes, “I love your hands.” When confronted with this seemingly incongruous message, from someone who claims to have been recently choked by the recipient’s hands, she said that she was intentionally referencing the thing that had hurt her.

[86] Ms. DeCoutere attempted to explain this correspondence as an effort at “flattening the negative” or normalizing a relationship. I acknowledge that the Court must guard against assuming that seemingly odd reactive behaviour of a complainant necessarily indicates fabrication. However, this is an illustration of the witness’s actual behaviour, evidenced by her own written expressions. It is behaviour that is out of harmony with her evidence in-chief and her multiple pre- trial statements to the media and to the police.

[87] In the framework of a credibility analysis in a criminal trial, Ms. DeCoutere’s attempt to hide this information evidences a manipulative course of conduct. This raises additional and mounting concerns regarding her reliability as a witness.

[88] In trying to reconcile the apparent disconnect between Ms. DeCoutere’s evidence and some of the established facts, another perhaps more subtle but related concern needs to be identified. It may be entirely natural for a victim of abuse to become involved in an advocacy group. However, the manner in which Ms. DeCoutere embraced and cultivated her role as an advocate for the cause of victims of sexual violence may explain some of her questionable conduct as a witness in these proceedings.

[89] On December 9, 2014, she told S.D., that she, Ms. DeCoutere, the professional actor, was excited for the trial because it was going to be “…theatre at its best.” “…Dude, with my background I literally feel like I was prepped to take this on, no shit.” “…This trial does not freak me out. I invite the media shit.”

[90] Ms. DeCoutere engaged the services of a publicist for her involvement in this case. She gave 19 media interviews and received massive attention for her role in this case. Hashtag “ibelievelucy” became very popular on Twitter and she was very excited when the actor Mia Farrow tweeted support and joined what Ms. DeCoutere referred to as the “team”. In an interview with CTV news, Ms. DeCoutere even analogized her role in this whole matter to David Beckham’s role as a spokesperson with Armani.

[91] I have to consider whether as a member of this “team”, Ms. DeCoutere felt that she had invested so much in being a “heroine” for the cause that this may have been additional motivation to suppress any information that, in her mind, might be interpreted negatively. I do not have sufficient evidence to conclude that this was in fact a reason for suppressing evidence, but in light of the amount of compromising information that she wilfully attempted to supress, it cannot be ignored as a live question.

[92] In her email correspondence with one of the other complainants, exchanged after the charges were laid, Ms. DeCoutere expressed strong animosity towards Mr. Ghomeshi. She said she wanted to see that Mr. Ghomeshi was “fucking decimated” and stated, “the guy’s a shit show, time to flush”; and then very bluntly just, “Fuck Ghomeshi”.

[93] All of the extreme animosity expressed since going public with her complaint in 2014 stands in stark contrast to the flirtatious correspondence and interactions of 2003 and 2004, words and actions that are preserved in the emails and photographs she says she forgot about.

[94] Let me emphasize strongly, it is the suppression of evidence and the deceptions maintained under oath that drive my concerns with the reliability of this witness, not necessarily her undetermined motivations for doing so. It is difficult to have trust in a witness who engages in the selective withholding relevant information.

THE EVIDENCE OF MS. DUNSWORTH

[95] Ms. Dunsworth, a close friend of Ms. DeCoutere, gave a sworn statement to the Halifax police in November of 2015 in which she stated that at some point, about 10 years ago, Ms. DeCoutere spoke to her about a choking incident that had occurred while she was on a date with Mr. Ghomeshi. Ms. DeCoutere wondered if her friend agreed that it was “weird”. This evidence was tendered for the very limited purpose of offsetting any implied allegation of “recent fabrication” that may have arisen from the cross-examination of Ms. DeCoutere.

[96] Shortly before Ms. Dunsworth was interviewed by the police, Ms. DeCoutere contacted her to advise her that the police needed to speak to her. She told her friend that she had already advised the police that she had told Ms. Dunsworth “AGES ago”, (in capital letters for emphasis I assume) about what had happened with Mr. Ghomeshi. She added, “It makes me look like I am not a copycat…”. The response from Ms. Dunsworth was, “corroborate ha ha” … “ya, no prob”.

[97] At the time that this evidence was tendered, I admitted it into evidence because I was concerned that it might ultimately be inferred that the complaint was fabricated in 2014. To be clear, this was my concern at the time. Counsel for the accused did not make an express allegation of “recent” fabrication in this case.

[98] The rule of evidence against the admissibility of this sort of earlier statement of a witness is a rule against “self-corroboration”. Having spoken of something similar a decade ago does not make the present allegation anymore true or false. The fact of the earlier discussion simply offsets any inference that it was fabricated in 2014. Being consistent is a trait that can be common to either the truth or a lie, and so is logically no more probative of the substance of the evidence at trial being true or being false.

[99] Ms. Dunsworth’s evidence places Ms. DeCoutere’s private complaint well before the public events of 2014. Apart from this limited use, the evidence is of little assistance with respect to the general veracity of Ms. DeCoutere’s evidence at trial.

THE COMPLAINT OF S.D.

[100] The charge relating to S.D. alleges a sexual assault said to have occurred sometime between July 15th, 2003 and the 2nd of August 2003.

[101] The allegation is that on the material date, while “making out” on a secluded park bench, Mr. Ghomeshi squeezed S.D.’s neck forcefully enough to cause discomfort and interfere with her ability to breathe.

[102] At the time of these events, S.D. was a dancer in a production performing in a Toronto park. She knew, or at least knew of, Mr. Ghomeshi through her involvement in the arts and entertainment industry. Following a particular performance, Mr. Ghomeshi approached her and initiated a conversation. This led to a dinner date and a second post-performance meeting in the park.

[103] It was after dark. S.D. and Mr. Ghomeshi strolled to the baseball diamond for privacy. They sat on a bench and kissed. She felt his hands and his teeth on and around her neck. It was rough and it was unwelcome. It was “not right” and it caused her difficulty in breathing. It lasted a few seconds. Nothing was said about it at the time.

[104] S.D. and Mr. Ghomeshi socialized two or three more times in the days and weeks following this incident in the park, and then had no further relationship. This is the extent of what S.D. initially related to the police.

[105] S.D. was not particularly precise or consistent in the details of the alleged assault. She explained that some of the imprecision in her initial account to the police was due to her still “trying to figure it out”.

[106] Some lack of precision is to be expected in any report of conduct from over a decade earlier. However, it is reasonable to expect that a true account of significant events will not vary too dramatically from time to time in the telling. The standard of proof in a criminal case requires sufficient clarity in the evidence to allow a confident acceptance of the essential facts. This portion of S.D.’s evidence at trial illustrates my concern on this last point:

He had his hand – it was sort of – it was sort of his hands were on my shoulders, kind of on my arms here, and then it was – and then I felt his teeth and then his hands around my neck. … It was rough but – yeah, it was rough.

Q. Were his hands open, were they closed?

A. It’s really hard for me to say, but it was just – I just felt his hands around my neck, all around my neck. … And I – I think I tried to – I tried to get out of it and then his hand was on my mouth, sort of smothering me.

Q. Okay. I’m going to go back. So the hands were around your neck. How long were they around your neck?

A. Seconds. A few seconds. Ten seconds. I don’t even – I don’t – it’s hard to know. It’s hard to know.

Q. And did his hands around your neck cause you any difficulties breathing?

A. Yes.

Possible Collusion

[107] S.D. said that her decision to come forward was inspired by others coming forward in 2014. She consumed the media reports and spoke to others for about six weeks after the “Ghomeshi Scandal” broke in the media. Although she initially testified that she and Ms. DeCoutere never discussed the details of her experience prior to her police interview, in cross-examination she admitted that in fact she had.

[108] I am alert to the danger that some of this outside influence and information may have been imported into her own admittedly imprecise recollection of her experience with Mr. Ghomeshi.

[109] The extreme dedication to bringing down Mr. Ghomeshi is evidenced vividly in the email correspondence between S.D. and Ms. DeCoutere. Between October 29, 2014 and September 2015, S.D. and Ms. DeCoutere exchanged approximately 5,000 messages. While this anger and this animus may simply reflect the legitimate feelings of victims of abuse, it also raises the need for the Court to proceed with caution. Ms. DeCoutere and S.D. considered themselves to be a “team” and the goal was to bring down Mr. Ghomeshi.

[110] The team bond between Ms. DeCoutere and S.D. was strong. They discussed witnesses, court dates and meetings with the prosecution. They described their partnership as being “insta sisters”. They shared a publicist. They initially shared the same lawyer. They spoke of together building a “Jenga Tower” against Mr. Ghomeshi. They expressed their top priority in the crude vernacular that they sometimes employed, to “sink the prick,… ‘cause he’s a fucking piece of shit.”

The Last Minute Disclosure

[111] S.D. met with Crown counsel five times in the year prior to the trial of this matter. On each occasion she was reminded of the need to be completely honest and accurate. At no time until almost literally the eve of being called to the witness stand did she reveal the whole truth of her relationship with Mr. Ghomeshi. The most dramatic aspect of S.D.’s evidence was her last-minute disclosure to the prosecution of sexual activity with Mr. Ghomeshi on a date following the date of the alleged assault in the park.

[112] It is now apparent that in her initial interviews, S.D was putting forward her non-association with Mr. Ghomeshi after the assault, as evidence that she had reason to fear him. She said that she “always kept her distance” from Mr. Ghomeshi. She felt unsafe around Mr. Ghomeshi. In her statement to the police she acknowledged that she went out a couple of times with Mr. Ghomeshi after the alleged assault but underscored that it was always in public. She told the police that “the extent of it is, we’re going to be in public.” They went to a bar and they had a dinner date.

[113] At trial, a very different truth was revealed. After meeting with Mr. Ghomeshi at a bar, in public, she took him back to her home and, to use her words, they “messed around”. She gave him a “hand job”. He slept there for a while then went home. This of course was dramatically contrary to her earlier statement that she “tried to stay in public with him” and keep her distance. S.D. acknowledged that her earlier comments were a deliberate lie and an intentional misrepresentation of her brief relationship with Mr. Ghomeshi.

[114] S.D.’s decision to supress this information until the last minute, prior to trial, greatly undermines the Court’s confidence in her evidence. In assessing the credibility of a witness, the active suppression of the truth will be as damaging to their reliability as a direct lie under oath.

[115] S.D. claimed that she did not think it was important to disclose this intimate contact and said she wasn’t “specifically” asked about post-assault sexual activity with Mr. Ghomeshi. She ultimately acknowledged that she left out things because she felt it didn’t fit “the pattern”. And when pressed further in cross-examination, she said that she did not think that what had happened between them at her home qualified as “sex”.

[116] On February 25, 2004, more than six months after the alleged assault in the park, S.D. sent Mr. Ghomeshi an email which included her asking him, “Still want to have that drink sometime?” These are not the words of someone endeavouring to keep her distance.

[117] When S.D. decided to make this disclosure, the other two complainants had already given evidence and had been seriously embarrassed when confronted with their own dramatic non-disclosures. S.D. had reviewed her sworn police complaint the week prior to trial and at that time offered no additions, qualifications or corrections. She says that she inadvertently heard something on the radio about emails being presented to the other complainants. She realized at that point that everything was going to come out and that it was time to disclose the true extent of their relationship.

[118] I accept Ms. Henein’s characterization of this behaviour. S.D. was clearly “playing chicken” with the justice system. She was prepared to tell half the truth for as long as she thought she might get away with it. Clearly, S.D. was following the proceedings more closely than she cared to admit and she knew that she was about to run head first into the whole truth.

[119] S.D offered an excuse for hiding this information. She said that this was her “first kick at the can”, and that she did not know how “to navigate” this sort of proceeding. “Navigating” this sort of proceeding is really quite simple: tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

THE FRAMEWORK OF ANALYSIS

[120] The fundamental framework of analysis in a criminal trial is often left significantly abbreviated in judge-alone trials. In this case, however, it is important to state this framework clearly. It plays the central role in the determination of this matter.

The Presumption of Innocence

[121] The primary and overarching principle in every criminal trial is the presumption of innocence. This is the most fundamental principle of our criminal justice system. It is essential to understand that this presumption of innocence is not a favour or charity extended to the accused in this particular case. To be presumed innocent until proven guilty by the evidence presented in a court of law, is the fundamental right of every person accused of criminal conduct.

Proof Beyond Reasonable Doubt

[122] Interwoven with the presumption of innocence is the standard of proof required to displace that presumption. To secure a conviction in a criminal case the Crown must establish each essential element of the charge against the accused to a point of “proof beyond reasonable doubt”. This standard of proof is very exacting. It is a standard far beyond the civil threshold of proof on a balance of probabilities.

[123] The law recognizes a spectrum of degrees of proof. The police lay charges on the basis of “reasonable grounds to believe” that an offence has been committed. Prosecutions only proceed to trial if the case meets the Crown’s screening standard of there being “a reasonable prospect of conviction”. In civil litigation, a plaintiff need only establish their case on a “balance of probabilities”. However to support a conviction in a criminal case, the strength of evidence must go much farther and establish the Crown’s case to a point of proof beyond a reasonable doubt. This is not a standard of absolute or scientific certainty, but it is a standard that certainly approaches that. Anything less entitles an accused to the full benefit of the presumption of innocence and a dismissal of the charge.

[124] The expression proof “beyond a reasonable doubt” has no precise definition, but it is well understood. The Supreme Court of Canada outlined a suggested model jury charge in R. v. Lifchus1. This is the definitive guide for criminal trial courts in Canada. It is worth setting out here verbatim:

— The term “beyond a reasonable doubt” has been used for a very long time and is a part of our history and traditions of justice. It is so ingrained in our criminal law that some think it needs no explanation, yet something must be said regarding its meaning.

— A reasonable doubt is not an imaginary or frivolous doubt. It must not be based upon sympathy or prejudice. Rather, it is based on reason and common sense. It is logically derived from the evidence or absence of evidence.

— Even if you believe the accused is probably guilty or likely guilty, that is not sufficient. In those circumstances you must give the benefit of the doubt to the accused and acquit because the Crown has failed to satisfy you of the guilt of the accused beyond a reasonable doubt.

— On the other hand you must remember that it is virtually impossible to prove anything to an absolute certainty and the Crown is not required to do so. Such a standard of proof is impossibly high.

— In short if, based upon the evidence before the court, you are sure that the accused committed the offence you should convict since this demonstrates that you are satisfied of his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

I instruct myself accordingly.

The Historical Nature of the Complaints

[125] The allegations before the Court in this case are legally referred to as “historical complaints” in the sense that they are complaints made now with respect to events that occurred many years ago. The courts recognize that trials of long past events can raise particular challenges due to the passage of time. Memories tend to fade, and time tends to erode the quality and availability of evidence.

[126] Each of the complainants in this case pointed to certain aspects of the publicity surrounding Mr. Ghomeshi’s very public termination from the CBC in 2014 as the trigger for coming forward with their complaints more than a decade after the fact. The law is clear: there should be no presumptive adverse inference arising when a complainant in a sexual assault case fails to come forward at the time of the events. Each complainant articulated her own very valid reasons for not coming forward at the time of the events. The law also recognizes that there should be nothing presumptively suspect in incremental disclosure of sexual assaults or abuse. Each case must be assessed individually in light of its own unique set of circumstances.

Similar Act Evidence

[127] Similar act evidence is presumptively inadmissible. Evidence of an accused’s alleged propensity to commit the particular type of crime with which he is charged with is inadmissible. The Crown expressly agreed that each complaint contained in the Information before the Court must be determined on its own merits.

CONCLUSIONS

[128] I have very deliberately considered the evidence relating to each of the charges separately. Each complainant in this case had a different and unique experience with Mr. Ghomeshi. However, there are certain common aspects to their cases. Each had some involvement in the arts and entertainment world, which brought them into contact with the accused: an event-catering waiter; an actor; and a dancer. Each complainant accused him of a certain act of violence in the context of a brief dating relationship. Each one chose not to make a complaint to the authorities until years after the fact. Each one came forward in 2014 in the wake of, or in the midst of, the extensive publicity surrounding the very public termination of Mr. Ghomeshi at the CBC.

[129] Each complainant chose to come forward to the media first and then subsequently gave sworn video-recorded statements to the police.

[130] Each complainant was aware of Mr. Ghomeshi and his celebrity status prior to meeting him. Each was a fan to some greater or lesser extent. Each had a brief relationship with him that ended badly. Each one complains of some degree of violence occurring in the course of some intimacy: a very forceful yank on the hair; being grabbing by the hair and punched in the head; a choke hold with slaps to the face and hands squeezing at the neck. Each event passed as quickly as it occurred. Each complainant acknowledged maintaining some brief, amicable contact with the accused after the fact and then moving on. These were the complaints that gave rise to the charges before this Court.

[131] There is no legal bar to convicting on the uncorroborated evidence of a single witness. However, one of the challenges for the prosecution in this case is that the allegations against Mr. Ghomeshi are supported by nothing in addition to the complainant’s word. There is no other evidence to look to determine the truth. There is no tangible evidence. There is no DNA. There is no “smoking gun”. There is only the sworn evidence of each complainant, standing on its own, to be measured against a very exacting standard of proof. This highlights the importance of the assessment of the credibility and the reliability and the overall quality, of that evidence.

[132] At trial, each complainant recounted their experience with Mr. Ghomeshi and was then subjected to extensive and revealing cross-examination. The cross-examination dramatically demonstrated that each complainant was less than full, frank and forthcoming in the information they provided to the media, to the police, to Crown counsel and to this Court.

[133] Ultimately my assessment of each of the counts against the accused turns entirely on the assessment of the reliability and credibility of the complainant, when measured against the Crown’s burden of proof. With respect to each charge, the only necessary determination is simply this: Does the evidence have sufficient quality and force to establish the accused’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt?

[134] Mr. Ghomeshi did not testify and he called no evidence in defence of the allegations. One of the most important organizing principles in our criminal law is the right of an accused not to be conscripted into building a case against oneself. Every accused facing criminal allegations is entitled to plead not guilty and put the Crown to the strict proof of the charges. An accused has every right to remain silent, call no evidence and seek an acquittal on the basis that the Crown’s case fails to establish his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. No adverse inference arises from his decision to do so in this case.

[135] As I have stated more than once, the courts must be very cautious in assessing the evidence of complainants in sexual assault and abuse cases. Courts must guard against applying false stereotypes concerning the expected conduct of complainants. I have a firm understanding that the reasonableness of reactive human behaviour in the dynamics of a relationship can be variable and unpredictable. However, the twists and turns of the complainants’ evidence in this tria, illustrate the need to be vigilant in avoiding the equally dangerous false assumption that sexual assault complainants are always truthful. Each individual and each unique factual scenario must be assessed according to their own particular circumstances.

[136] Each complainant in this case engaged in conduct regarding Mr. Ghomeshi, after the fact, which seems out of harmony with the assaultive behaviour ascribed to him. In many instances, their conduct and comments were even inconsistent with the level of animus exhibited by each of them, both at the time and then years later. In a case that is entirely dependent on the reliability of their evidence standing alone, these are factors that cause me considerable difficulty when asked to accept their evidence at full value.

[137] Each complainant was confronted with a volume of evidence that was contrary to their prior sworn statements and their evidence in-chief. Each complainant demonstrated, to some degree, a willingness to ignore their oath to tell the truth on more than one occasion. It is this aspect of their evidence that is most troubling to the Court.

[138] The success of this prosecution depended entirely on the Court being able to accept each complainant as a sincere, honest and accurate witness. Each complainant was revealed at trial to be lacking in these important attributes. The evidence of each complainant suffered not just from inconsistencies and questionable behaviour, but was tainted by outright deception.

[139] The harsh reality is that once a witness has been shown to be deceptive and manipulative in giving their evidence, that witness can no longer expect the Court to consider them to be a trusted source of the truth. I am forced to conclude that it is impossible for the Court to have sufficient faith in the reliability or sincerity of these complainants. Put simply, the volume of serious deficiencies in the evidence leaves the Court with a reasonable doubt.

[140] My conclusion that the evidence in this case raises a reasonable doubt is not the same as deciding in any positive way that these events never happened. At the end of this trial, a reasonable doubt exists because it is impossible to determine, with any acceptable degree of certainty or comfort, what is true and what is false. The standard of proof in a criminal case requires sufficient clarity in the evidence to allow a confident acceptance of the essential facts. In these proceedings the bedrock foundation of the Crown’s case is tainted and incapable of supporting any clear determination of the truth.

[141] I have no hesitation in concluding that the quality of the evidence in this case is incapable of displacing the presumption of innocence. The evidence fails to prove the allegations beyond a reasonable doubt.

[142] I find Mr. Ghomeshi not guilty on all of these charges and they will be noted as dismissed.

Released: March 24, 2016

Signed: “Justice William B. Horkins”