Remembering Maurice Strong, who tried to solve global warming decades ago

He called out climate change at a summit, decades before the latest one in Paris. Maurice Strong’s death on the eve of the conference reminds us to be skeptical.

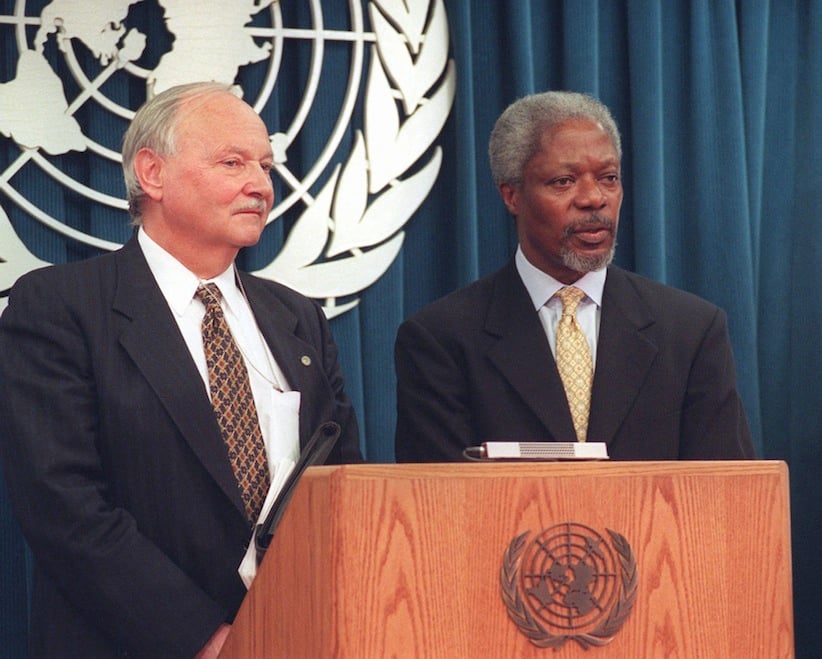

FILE – In a March 17, 1997 file photo, Maurice Strong, left, executive coordinator for United Nations reform, stands with United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan, during a news conference, at the U.N. The head of the U.N.’s environmental agency says Strong, whose work helped lead to the landmark climate summit that begins in Paris on Monday, Nov. 30, 2015, has died. He was 86. (AP Photo/Osamu Honda, File)

Share

Maurice Strong, who died a few days ago at 86, was a figure of endless intrigue around politics and business for decades, but never more so than in the early 1990s. As secretary general of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Strong was the driving force at that time behind the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, which started what we now know has been an endlessly frustrating struggle to come to grips with global warming.

In 1990, I interviewed him for the Financial Post about his preparations for Rio. On his death, I looked up that old Q&A and found his answers strikingly relevant to what’s being talked about this week at the UN’s latest climate change confab in Paris, called COP21. For instance, Strong said the “biggest single issue” was figuring out how the rich, developed countries would come up with sufficient billions to compensate poor, developing ones for building their economies with low carbon emissions. (He suggested dedicated taxes!) We still haven’t come close to solving that one.

He also said clear targets for cutting emissions would be needed, although of course everything wouldn’t be settled at the Rio summit alone. “But we do have to establish the basis for a major shift in direction,” he said. In all the years since, I don’t think anything that qualifies as a “major shift” has occurred. Weaning the world off fossil fuels has proven too painful, a topic on which Strong was surprisingly blunt, way back then. “It’s going to be disruptive; it’s going to change the status quo; it’s going to change competitive advantage,” he said.

Few leaders are willing to use words like “disruptive” these days, preferring platitudes about how economic growth and environmental protection go hand in hand. Still, far from projecting any sense of alarm, what Strong conveyed in 1990 (at least to an inexperienced reporter) was a magisterial sense of command over this daunting challenge. Climate change was just too dire too be ignored. It followed that a process was needed to forge a solution. Therefore, that is what would be done. He was, in fact, doing it.

Strong’s track record made it plausible that he might succeed. He had moved effortlessly between spheres of influence, from being president of Power Corp. in the 1960s to setting up the UN Environment Programme in the 1970s. Adjusting the globe’s thermostat seemed well within his technocratic range.

But what has happened since? Between 1990, when Strong made such an impression on me, and 2011, global greenhouse gas emissions soared 42 per cent, while Canada’s climbed 19 per cent.

And once again, at Paris just as it was at Rio, the talk is about this being the moment when the world must set itself a new course. Finally. Strong’s death on the eve of the latest conference compels us to be skeptical. Admirable though it was, his contribution wasn’t enough. The process he trusted—rational decision-making among determined decision-makers—has been vastly outgunned by entrenched economic interests.

We have no choice but to keep trying, although I doubt any UN mandarin today could convincingly hold forth on the prospects of success with Strong’s aplomb of a quarter-century ago.