Robert Latimer’s request for clemency is a slam-dunk ‘no.’ Does Ottawa get that?

Peter Stockland: The Trudeau government is hiding behind privacy laws on a case that reaches far beyond the interests of the man raising it

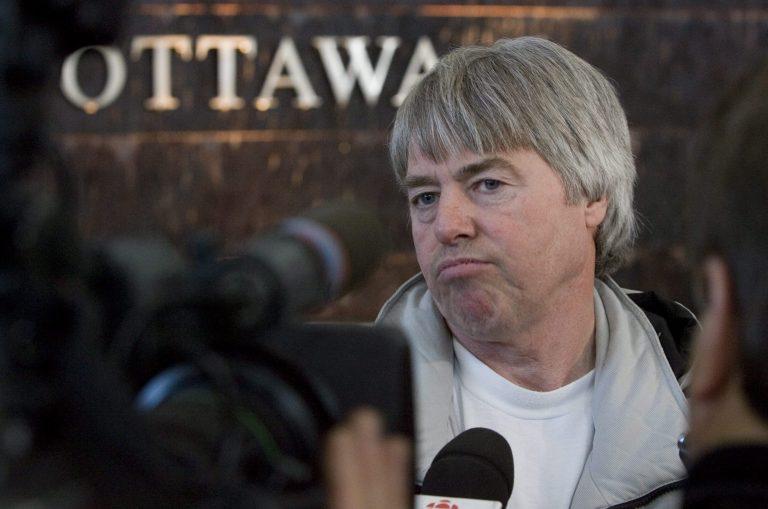

Latimer in 2008, when he sought to overturn his conviction for killing his severely disabled daughter Tracy THE CANADIAN PRESS/Tom Hanson

Share

Peter Stockland, a former editor-in-chief of the Montreal Gazette, is publisher of Convivium, an online forum for faith-based debate on public policy and social issues.

More than a month after reports that Robert Latimer applied to have his life sentence vacated and his record expunged, a shroud of ministerial silence still envelops the politically sensitive request.

Citing the federal Privacy Act, a spokesperson for Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould said this week the office could not comment even on the status of the application Latimer made to some media fanfare in early July.

On one level, it’s fair enough that the Saskatchewan farmer who put his severely handicapped daughter in a makeshift gas chamber to murder her should be entitled to the same protections of privacy law as any other Canadian.

At the same time, the justice minister’s reticence is curious given that Latimer, through his lawyer, made the appeal for the royal prerogative of mercy in publicized letters to her and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, and that the very government application for such relief requires consent to release of personal information and waiver of solicitor-client privilege. (It includes consent to disclose information to “another person or body” for the purposes of assessing the application; could discerning public attitudes be such a purpose?).

Beyond that, Latimer himself has never hesitated to volubly proclaim he did nothing wrong in 1993 when he put his 12-year-old daughter Tracy in the cab of his farm truck and pumped carbon monoxide in to kill her. As recently as October 2017, Latimer gave an interview to the Saskatoon StarPhoenix in which he insisted yet again: “What I did was right.”

RELATED: Federal Court overturns Robert Latimer’s travel restrictions

Such defiant lack of remorse, in the face of five legal proceedings affirming his guilt and sentence, might be deemed worthy of comment by a government that seldom feels the need to restrain its vocal enthusiasm on an array of issues, including criminal verdicts still subject to potential appeal. But no. Canadians must wait while the bureaucratic and cabinet process proceeds apace far out of public view until a fait accompli is presented.

Only then will we know whether the justice minister and the prime minister are prepared to go out on a limb and agree with Canadians who would have zero sympathy for an unrepentant convict who the court record shows considered poisoning, suffocating and shooting his own daughter in the head.

Of course, Robert Latimer is entitled to make his appeal. Our legal and political systems allow for clemency. Before the abolition of capital punishment, federal cabinets commuted death sentences. Parliament has power to redress proven historical injustices.

The operative word is proven. In Latimer’s case there is no shred of evidence, much less proof, that the outcome of his case constitutes an injustice. On the contrary, the Supreme Court of Canada accepted beyond doubt he was guilty of second-degree murder and deserved a life sentence with a 10-year mandatory minimum before parole eligibility.

Canadians who recall the 25-year-old killing know Latimer confessed, after initially lying to police.

In its 2001 decision upholding his conviction and sentence, the Supreme Court records that “Mr. Latimer…told police he had considered giving Tracy an overdose of Valium or ‘shooting her in the head’ to end her suffering from severe cerebral palsy. The court documents the alternatives open to Latimer such as surgery for Tracy or placement in a care facility, all of which he rejected in favour of killing her. “Tracy’s proposed surgery did not pose an imminent threat to her life, nor did her medical condition,” the court said in rejecting what is called the defence of necessity. “In fact, Tracy’s health might have improved had the Latimers not rejected the option of relying on a feeding tube. [Latimer] can be reasonably expected to have understood that reality.”

RELATED: Should mentally ill Canadians have access to assisted dying?

The true reality check, says an Ottawa lawyer who has argued high-profile cases around medical aid in dying (MAiD), is realizing that what Robert Latimer did was murder then and remains murder now regardless of changes to Canada’s assisted-suicide laws. And that matters, says Albertos Polizogopoulos, because of the risk of conflating Latimer’s crime with changes to Canadian law on medical aid in dying.

“What Robert Latimer did was illegal and wrong in 1993 and it would be illegal and wrong today even after the Carter decision,” says Polizogopoulos, who argued before the Supreme Court in 2015 in the case that legalized medically assisted death. “Carter did not legalize the mercy killing of children or people with cognitive disabilities. And Tracy didn’t have the mental capacity to make decisions. She would not qualify for MAiD under the current regime.”

The facts of the young girl’s death from carbon monoxide suffocation in the cab of a truck in a Saskatchewan farmyard put paid, Polizogopoulos argues, to the argument in Latimer’s application for ministerial review that Tracy was killed only because doctors failed to prescribe powerful opioids to manage her pain.

“That shows the frame of mind he was in at the time, and that he seems to still be in: there’s never been any expression of public remorse. A main criteria for remorse is clear acknowledgement that what you’ve done is wrong. His position seems to be that everyone else wrong, and he’s the real victim.”

For disability rights activist Taylor Hyatt, the very idea of confusing victim and perpetrator in the Latimer case raises deep concern about the application for ministerial review. While she has no immediate fear there is wide public or political support for erasing Latimer’s murder conviction, she sees significant danger ahead if the process clouds understanding of disabled life. And if the Prime Minister does, unimaginably, approve the washing away of Latimer’s crime?

RELATED: Assisted dying was supposed to be an option. To some patients, it looks like the only one

“You’re going to see a tremendous shift in the way that disability, and people who live with it, is treated by Canadian society,” she says. “Down the road, more people could be inspired to share Mr. Latimer’s views and act on them by judging from the outside that a life like mine or Tracy’s is not worth living. People will be put in very real danger.”

An outreach coordinator and policy analyst for the disability rights lobby group Not Dead Yet, Hyatt lives with cerebral palsy as Tracy Latimer did for the 12 years of her life, though its effect isn’t remotely as severe. It has taught her a great deal about assumptions Canadians still paternalistically make on behalf the disabled. She loathes, for example, the routine reference to her being “confined” to a wheelchair.

“It’s true I have to use it all the time, but I’m not confined to it. I’m liberated. Without it, I would not be able to get out and experience the world as I do.”

Latimer’s crime was exponentially more heinous, but it proceeded from the same presumptions made by many less lethally-minded Canadians, Hyatt says.

“He killed his minor daughter without her consent because of what he believed her life was like. Just because a way of life looks unfamiliar, even scary, even a thousand times harder than your own, don’t be quick to judge it is not worth living, and to impose your assumptions of a good life onto the life that is already there,” Hyatt says.

Canadians can but wait patiently to hear that the Prime Minister and his justice minister have heeded the wisdom of Hyatt’s words and firmly told Robert Latimer: “No.”