Sockeye salmon stocks are crashing. Long-lost notebooks saw it coming.

The detailed field journals, lost for decades, now reveal today’s salmon stocks are in dramatically worse shape than imagined

Darlene Gillespie opens a book filled with archival sockeye scales from 1913 at The Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo BC. (Photograph by Jen Osborne)

Share

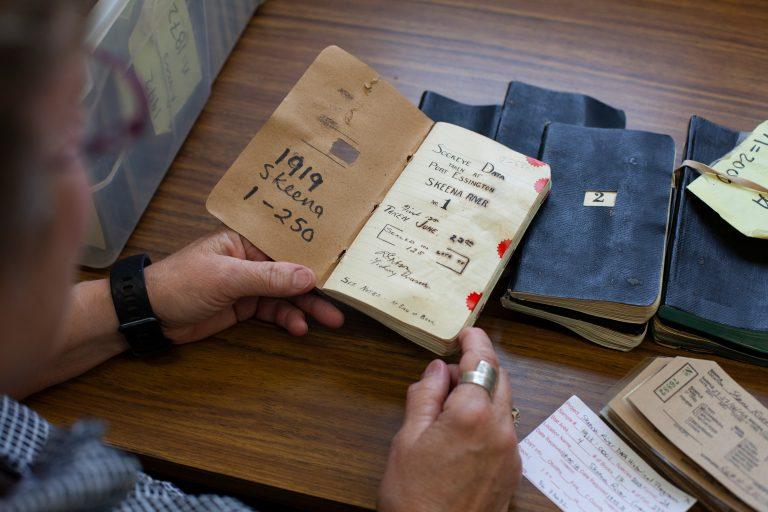

It was a rare window into the past: small black field notebooks from the first decades of the last century, pages swollen and yellowed with time, forgotten for more than 50 years.

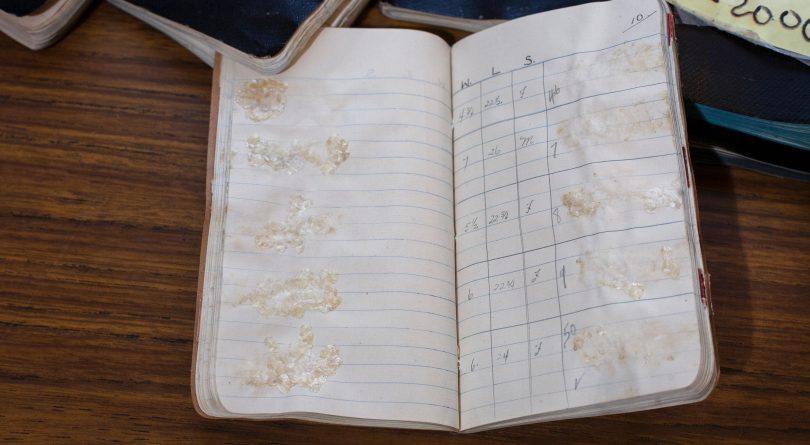

Inside, elegant notations in fountain pen—the ink sometimes blurred with oily residue—cataloguing the weight, length and sex of sockeye salmon, five fish to a page, column lines drawn freehand, pages tenderly numbered.

Here’s the entry one R. Gibson, fishery overseer, made on June 23, 1919, at Port Essington, B.C.: “Sockeye run surprisingly good for beginning of Season. Boats fishing in River average eight and boats outside with an average of fifteen.”

But along with written details of each sockeye—then caught by people in wooden rowboats using linen nets—were items so ancient and so ephemeral that, by rights, they ought not to exist today. Glued to each page with blood and slime was a treasure trove of ancient sockeye salmon scales, scraped by knife from the fish’s skin before it went to the cannery.

READ MORE: Brazen thieves are pinching lobster from East Coast fishermen

In all, scales and information were meticulously gathered from more than 65,000 sockeye, every year without fail from 1912 to 1948, by provincial officers monitoring commercial fisheries at the mouth of the Skeena River system near Prince Rupert, B.C.—Canada’s second-largest salmon superhighway after the Fraser River. Sockeye, with their red, oily flesh, are cherished by the commercial fishery and Indigenous communities. They also nourish eagles, orcas, grizzlies and scads of other creatures.

“I think this collection is regarded as one of the richest collections of fish scales in the world,” says Michael Price, who launched his Ph.D. studies in biological sciences at Simon Fraser University in 2016 to figure out what stories the scale collection could divulge.

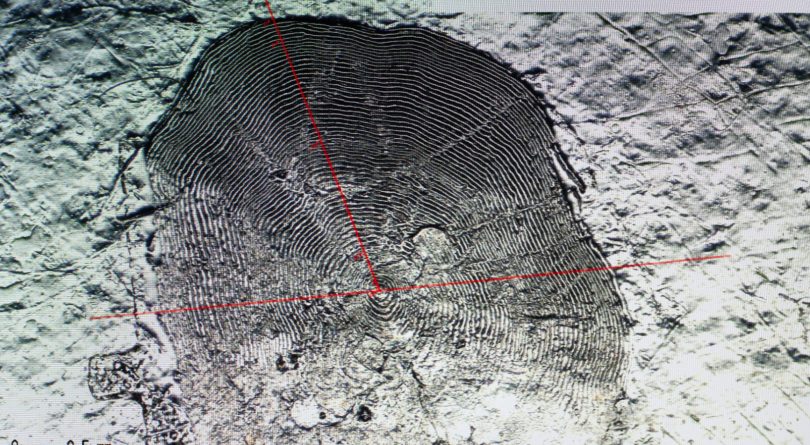

Many, as it turns out. Fish scales are a gold mine of information. By 1912, Charles Gilbert, a pioneering ichthyologist at Stanford University in California, had realized that microscopic, concentric circles of growth in sockeye scales could tell you how old the fish was—much like tree rings—as well as which parts of its life it had lived in salty and fresh water. Worried even then about sockeye decline, the B.C. government hired Gilbert to set up its monitoring program. Gilbert, in turn, taught fishery officers to collect both data and scales. Every year he examined the scales at Stanford and wrote a report for the government on the health of the sockeye.

But then the notebooks vanished. In the 1990s, Skip McKinnell, a sockeye oceanographer who once worked for the federal government, set out to find them, never dreaming they might still contain the scales. For a year, he searched archives from California to Alaska. Finally, he stumbled on the notebooks in a backroom of the Pacific Salmon Commission in Vancouver. Today, they’re stored at the Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo.

“There were boxes and boxes full of these booklets with scales in them,” McKinnell says. “Your jaw drops open.”

Techniques to read the scales’ genetic information—something Gilbert could never have imagined—hadn’t been invented, so the scales languished for another 20 years until Price arrived. The wait was worth it.

Price examined scales from 3,400 fish collected from 1913 to 1923, taking a digital image of each and extracting DNA. He grouped the sockeye into 13 geographically separate wild populations. Then he calculated how large each population was and compared each to corresponding populations in the eight-year period from 2007 to 2014.

The results, published in Conservation Letters in August, were so incredible that they have spawned a whole new analysis of the status of the sockeye. And that’s saying something for a fish that is among the most scrutinized in Canada—partly because it travels through lands and waters under the control of federal and provincial governments and First Nations, and also because it has been the source of so much wealth.

Before Price’s work, fisheries biologists used figures from the 1960s as the baseline for a healthy wild population, even though the commercial fishery on the Skeena began in 1877. According to that 1960s baseline, the sockeye population was in pretty good shape: only seven of 13 wild populations had declined by 2014 and only by a median of six per cent. But compared to Price’s figures from the early part of the 20th century, all 13 wild populations have crashed. The median drop is 82 per cent. The range runs from 56 per cent to 99 per cent. Not only that, but the bigger the fish, the sharper the decline, leaving smaller wild sockeye in general.

Listen to Alanna Mitchell talk about the long-lost salmon journals on The Big Story podcast.

Learn more at The Big Story Podcast.

It adds up to this: a century ago, about 1.8 million wild adult sockeye returned to the Skeena River each year. In the eight years ending in 2014, it was fewer than 500,000, and the fish have done more poorly since then, Price says. He added that degradation of the creeks doesn’t explain the huge declines. “It’s really death by 1,000 cuts,” he says. “It’s a combination of all our human actions that undoubtedly has contributed to their decline.”

Sockeye salmon begin their lives in lakes, then travel by river to the estuary and the open ocean, only to make the return journey to fresh water at the end of their lives to spawn. It’s a lot of different habitats subject to a lot of different changes over a century.

Many of those rivers are getting warmer and shallower in this era of climate disruption, a problem for cold-water-loving sockeye. The ocean is heating up, too, meaning it doesn’t produce as much food for salmon. In addition, a large warm area off the North American coast known as “the blob” has emerged again this year, affecting salmon in Canada and the United States.

“We have a salmon crisis,” says Greg Knox, executive director of the conservation organization SkeenaWild Conservation Trust. “We have to rethink our whole way of managing salmon, and that means significant reductions in harvest to just try to protect and rebuild them.”

The Pacific salmon industry is all too conscious of the crisis. Both in 2017 and this year, the sockeye fishery on the Skeena was closed because fish were too sparse, says Christina Burridge, secretary to the Canadian Pacific Sustainable Fisheries Society, which represents processors and exporters.

RELATED: How a Newfoundland fisherman became godfather to a generation of Tamil-Canadians

And, this month, the industry voluntarily withdrew its entire B.C. salmon catch from the Marine Stewardship Council, the organization that certifies fisheries as sustainable. That’s because the Canadian government has fallen behind in requirements to monitor and ensure the health of wild salmon in the Skeena and other areas, Burridge says.

In fact, government monitoring of salmon populations in streams has fallen to historic low levels since the 1980s, partly because of budget cuts. The government has too little information to assess the sustainability of about half the sockeye populations on the central and northern coasts, Price says.

Now, creek walkers, who for decades lovingly tracked the health of sockeye in remote streams, are being phased out. Long gone, too, are the days when inspectors wrote in their black books in fountain pen, carefully preserving each scale for all time. Today, the trend is to use airplanes to count fish across a few representative streams.

Indigenous communities are losing patience. They have the constitutionally protected right to fish, and they have watched salmon numbers drop for generations.

While they say the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans is trying to improve monitoring and establish rehabilitation plans, it’s too little, too late.

“Time is something we don’t have these days,” says Stu Barnes, chair of the Skeena Fisheries Commission and a member of the executive council of the First Nations Fisheries Council of B.C. He is Gitxsan from Kispiox. He called for a wholesale rethinking of the way the Skeena fishery is managed, including curbs on recreational fishing. People in his communities are feeling desperate. They live every day with the fallout from the vanishing sockeye.

“This is where it gets real. It’s cultural, social, emotional, spiritual—basically a decrease on all those parts of your life across the board,” he says. “We’re seeing suicides, we’re seeing rampant drug use, and it’s all because the activity of going fishing is now limited to the point that it’s non-existent for a lot of families.” He says there are so few sockeye now that the time-honoured skill of learning to fish can no longer be passed on to younger generations. “What are you going to do, go down to the river and stand there?” he asks.

RELATED: Reel justice prevails: This B.C. man won a 30-year battle to fish in a public lake

The urgency of all this reminds Malii (also known as Glen Williams), hereditary chief of the Gitanyow, of the abrupt foundering of the Newfoundland cod fishery in 1993. Considered by scientists as one of the planet’s most significant modern ecological disintegrations, its effects continue to cascade through the marine environment.

Malii sees a parallel in the “reckless” management of the wild Pacific sockeye salmon fishery. “If we don’t take action over the next year or two, it’s going to be like the cod fishery of the East Coast,” Malii says. “That’s exactly what’s going to happen.”

He longs for a return to the time when the Gitanyow and other Indigenous communities could rely on the food security of healthy wild sockeye runs in the Skeena.

“My grandparents were telling me, and my parents were saying, that some of the creeks here were just full of sockeye,” he says. “You could practically walk across the creeks, they were so full of sockeye and other species.”

Gilbert, the Stanford fish biologist, died in 1928. But the years of cutting-edge monitoring in those notebooks had him recommending conservation measures to save the sockeye even then. It didn’t work. And now the dearth of the monitoring he so exactingly put in place draws into question whether it’s even possible to correct a century of declines.

“There were warning signs there almost from the beginning, and we didn’t heed them,” Price says. “That blows me away.”